Nachum Sparks and the Mystery of the Missing Menorahs: Ch 2

| December 2, 2025Aha, so the spy gets spied on for a change, I thought with a sense of satisfaction I will not try to deny

Illustrated by Esti Saposh

Previously:

A wheelchair-bound Nachum spends his time on the mirpesset, learning Gemara and observing the routines and rhythms of Jerusalem city life. Aryeh catches Minchah at Shtilerman’s, a local shtibel, and notices a beautiful menorah set up for Chanukah. Later that day, he and Nachum are discussing their dirah’s Chanukah programming when they spot a drone in the sky, which Nachum warns is heading straight for them.

Thursday evening, December 11th

N

achum was not mistaken.

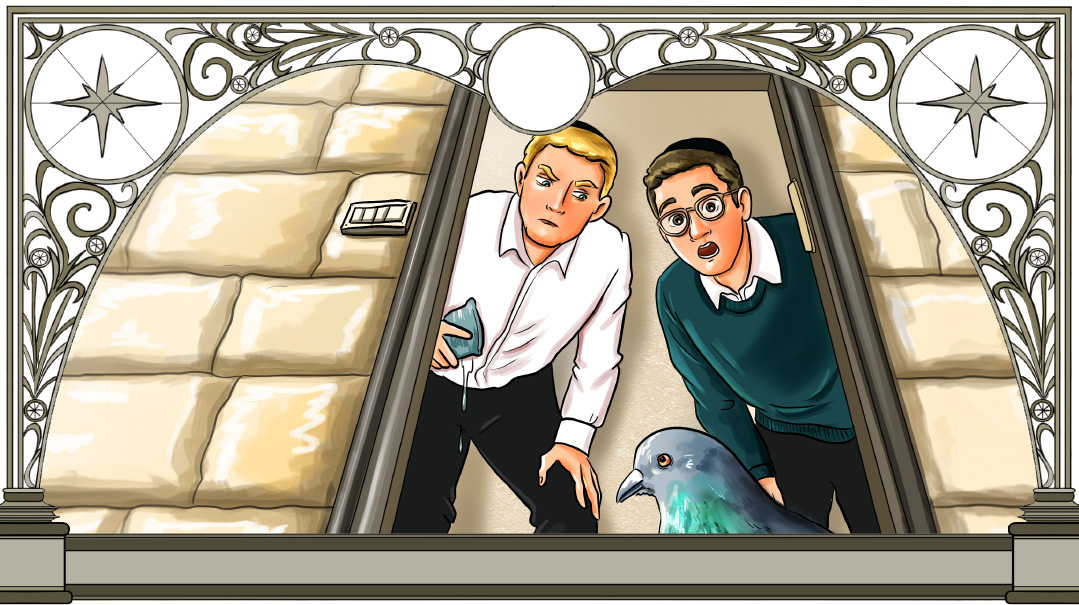

The drone’s mini propellers spun until it was directly above him. Slowly, it began to descend until it was eye level with him in his wheelchair. Then, it dropped two packages onto his lap before beginning to fly upward. We watched it disappear into the night sky.

“That was cool,” I said. “But what are those packages? Are they safe to open?”

My roommate was holding one to each ear. “I have already determined that they’re not explosive. The next question is whether they contain poison.” He sniffed them. “I think they’re fine, but if I start reacting, Rosen, kindly call MADA immediately.”

With some trepidation, I watched Nachum’s fingers slowly start to peel back the brown wrapping paper.

The first one was a… bouquet of flowers? Attached to its stems was a teddy bear with the words, “refuah sheleimah.” The second package was a boxed silver menorah.

Nachum set both down on the mirpesset with a bit more force than was necessary.

“Well then, I think we can safely assume who they’re from,” he said.

Just then, Nachum’s phone rang. I could discern the distinctly nasal tone of Nachum’s older brother, Myron. (Myron is a Mossad agent who uses his counterintelligence resources to both foil terrorist plots and pick on his younger brother.)

“Fine, I’ll put you on speaker,” I heard Nachum say.

“Hello, Aryeh. Nice sweater you’re wearing. I enjoyed reading the ‘Case of the Kohein Club’ on your Substack. The writing is slowly improving, but your syntax could still use some work. And dear brother, is that how you thank me for taking time out of my busy schedule to send you a get-well and Chanukah gift? By throwing them on the floor? If you don’t put the flowers in water, Nachum, you’ll never see the daffodils open.”

“I don’t care about the daffodils.” Nachum’s fingers were tightly gripping the sides of his wheelchair.

Aha, so the spy gets spied on for a change, I thought with a sense of satisfaction I will not try to deny.

“I’m up to big stuff,” Myron’s high-pitched voice continued. “Can’t tell you more about it at the moment, Nachum. Strictly confidential. Suffice it to say that I’ve just returned from Doha and you’ll be reading about something big in the news tomorrow. How about you? Found a kid’s missing shoe? Well done!”

Even in the dark of night, I could see Nachum’s face changing colors.

“I was watching you watching them but I had to go into a work meeting when the father called the mother,” continued Myron. “It was in the toy bin, I presume?”

“Yes, it was in the toy bin.”

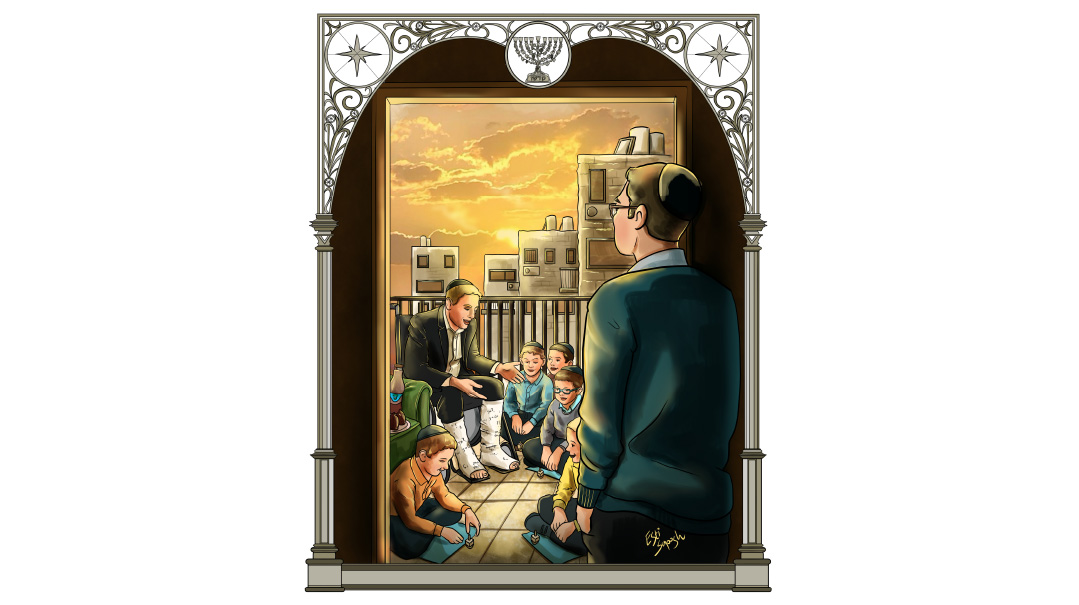

“Well, I do not envy your inability to move, though you certainly have no shortage of opportunities to practice your deductive reasoning. Take that man pacing on the mirpesset on top of the Yesh grocery store. You see him?”

“Yes, just got out of Miluim.”

“Indeed,” said Myron. “Home only a few days.”

“Has been in Gaza for a while.”

“Lebanon, dear brother, Lebanon.”

“And he hasn’t been home since right after Succos.”

“Poor family,” continued Myron. “They’ve missed him so much. He’s a very devoted father.”

“Yes,” agreed Nachum, “very devoted to his baby boy and five-year-old daughter.”

“Twin daughters, dear brother. My, you’re off your game tonight.”

I didn’t mean to laugh out loud, but were these two for real?

“Need an explanation for our inferences then, Rosen?” my roommate said, with his uncanny ability to read my unspoken thoughts. I nodded.

“Well, surely it’s obvious even to you,” Nachum explained, “that the man has the stiff posture of a military man. He walks with his shoulders slightly misaligned, a sign he’s been carrying a gun on his shoulder for an extended period of time.”

“His muddy combat boots are visible from the sliding doors to the house,” Myron continued, “but the gravel on them is too coarse to be from Gaza. The terrain in Lebanon is far rockier.”

“He’s been there since Succos,” picked up Nachum, “since his succah is still up and you can see he has his power tools out on the mirpesset to take it down now.”

“He got back a day or so ago because there’s still a lot of helium in the ‘Welcome Home’ balloon you see floating above the baby’s bassinet in the living room.”

“But there is also a pile of children’s books on the coffee table,” Nachum said, “so we can infer there are older kids in the house as well.”

“And we can know that those kids — Noa and Hila — are twins,” finished Myron, “because there are two gan-made menorahs already set up on the table by the window. Except for their names, written in marker with a morah’s practiced hand on both, the menorahs are virtually identical, meaning the girls both made them in the same gan. Perhaps, Aryeh, you will counter that they went to that gan in different years, and projects are repeated year after year—”

“But that can’t be,” said Nachum, “because if that were the case, the marker ink on one would be more faded than on the other.”

“Yes, of course,” I affirmed, because I had totally been thinking of that counterargument and was definitely not still processing the fact that the girls were twins.

“Well then,” concluded Myron, “I’ll wish you a refuah sheleimah and Chanukah samei’ach. Think of me when you light the menorah I sent. I’ll know if you don’t, and I will be insulted.”

“Thank you, Myron,” Nachum said, sounding anything but thankful.

“And do try to limit your sufganiyah consumption this year. Remember when you ate too many at Grandma Gita’s Chanukah party and threw up all over her sewing machine?”

Nachum’s knuckles were white against the black of his armrests. “I was eight years old then, Myron.”

“Yes, and you haven’t advanced much from that point in time, have you?”

“Ah freilechen Chanukah, Myron.”

“Same to you, dear brother.”

The phone clicked off. I knew the conversation had put Nachum in a foul mood because he wheeled himself over wordlessly to the viola in the corner and began playing his repertoire of slower, more sorrowful-sounding klezmer songs.

The next two days passed in a blur of bechinah-studying for me and wick-rolling for Nachum, who couldn’t fathom that I bought my wicks already rolled.

“I won’t light Myron’s menorah,” Nachum said as the cotton strands turned to strings in his hands. “I don’t care if he’s insulted. I broke my legs getting my menorah, and that’s the only one I’ll use.”

Before I knew it, we had arrived at one of my favorite moments of the entire year: candlelighting of the first night of Chanukah. Nachum and I lit inside, but went out on the mirpesset to sing his father’s favorite, yekkish tune for Haneiros Halalu. From between our soragim, the twinkling candle lights dotting the Jerusalem cityscape looked to me like stars that had fallen from the sky. We began breaking into our first sufganiyah contender — a snowy-white confection from Angel’s Bakery — when I noticed Nachum slowly lowering his doughnut onto his plate.

He was staring in the direction of Shtilerman’s shtibel with a very strange look on his face. I saw him look down at his watch and back at the shtibel.

“A discordant note,” he said at last.

“What do you mean, Sparks?”

“It’s 5:07, is it not?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Doesn’t that seem a little too early for the menorah in Shtilerman’s to already be out?”

“I guess so. I wouldn’t think too much of it though.”

Nachum’s eyes were fixed on the shtibel’s black windows. “Why is the shtibel completely dark at this hour? The menorah was lit right before Aleinu. I would have expected it to stay lit for at least another hour.”

“Yeah, but menorahs go out early sometimes, Sparks.”

“Hmm… perhaps you are right. It strikes me as a discordant note though, Rosen. I confess that I don’t have a good feeling about it.”

I watched as he took the pen on his shtender and etched the numbers 5:07 onto his cast.

Two hours later, deep into Maseches Yevamos, we heard Nachum’s phone ring.

“Eliad?” Jerusalem’s Chief Police Inspector was on the line.

“Nachum, yeish lanu matzav,” I could overhear.

“Where?” asked my roommate.

“A shul in your neighborhood. It’s called Shtilerman’s.”

Monday morning, December 15th

“Y

es, your majesty,” I mumbled.

“What was that, Rosen? Try to project when you speak.”

“It’s hard to talk when you’re moving a heavy… never mind.” On my shoulder, I had the tattered armchair Nachum’s clients sat on when they came to consult with him. We were moving it to the mirpesset so Nachum could conduct meetings in his man-cave instead of having to, chas v’chalilah, exert himself to wheel his chair inside.

“A little more to the right,” Nachum said, his finger moving up and down in what looked like finger jumping jacks.

“I get it, I get it,” I said between breaths for air. “You don’t need to keep pointing with your finger.”

“I’m not pointing, Rosen. I’m exercising my finger muscles.”

“Why?”

“For my new dreidel chug.”

“Your new dreidel what?” I wasn’t sure I heard correctly.

“I’ve perfected a method for spinning a gimmel every time you spin.”

“That’s impossible.”

“Watch me.”

Eighteen “gimmel” spins later and I had to reluctantly admit that Nachum was on to something.

“How do you do it?” I demanded.

“It’s a combination of knuckle strength and physics. You’ll have to come to the chug to hear the rest.”

“Who else will be there?”

“Yehuda Gershonowitz and his friends.” Yehuda was our seven-year-old downstairs neighbor. “He kept losing all of his chocolate coins in cheder,” Nachum explained, “so I told him I would help him perfect his method.”

“Next thing I know,” I said skeptically, “you’ll be doing a klafim chug: how to use physics to get the cards to turn over without destroying the palms of your hands.”

Nachum’s eyes were giant blue orbs. “Rosen, that’s actually a brilliant idea.”

“I have them every so often, Sparks. Don’t look so stunned.”

A knock from inside signified the arrival of our newest client. I went in to direct Reb Yoel Laufer through the mess of our living room to our only slightly-less-messy mirpesset.

“Shalom aleichem, Reb Aryeh, Reb Nachum,” Reb Yoel warmly extended one white-shirted arm toward Nachum and the other toward me.

“Aleichem shalom, Reb Yoel,” Nachum said, proffering a hand from his wheelchair. “How’s the arthritis?”

“Baruch Hashem yom, yom. The Rebbetzin wants me to switch to a new orthope — wait — when did I tell you about my arthritis? Reb Aryeh was by us last week, but we haven’t had you in the shtibel for too long, Reb Nachum.”

“You didn’t tell me, Reb Yoel, I heard the grinding of your knee cap when you came in. Also, the protrusion of your left pant leg tells me you’re wearing a brace. Is it helping?” Nachum asked, sounding sympathetic.

“A little,” Reb Yoel answered, as he sat down slowly in the armchair I had deposited there just moments earlier. “Only a little,” he rubbed his kneecap with his hand. “But I can’t complain. Not to someone with two broken legs and not on a beautiful Chanukah morning like this one.” He smiled at the view from our mirpesset.

“It’s beautiful but a bit chilly. Let me make you a coffee,” said Nachum.

Reb Yoel held two hands up and waved them downward. “No, no, I don’t want to be matriach….”

“No trouble at all,” answered my roommate, reaching for his train remote. I saw Reb Yoel’s eyes widen in astonishment as they followed the curve of the train carrying his freshly-brewed mug of coffee across our mirpesset tiles. “Geonis, just geonis,” he said when the steaming mug stopped with a toot, toot by his feet.

As he reached down to retrieve it, Nachum asked, “So tell me, Reb Yoel, what happened at Shtilerman’s last night? Eliad told me the basics, but I’d like to hear your account.”

I watched Reb Yoel make a brachah and take a long sip. “It went like this, Reb Nachum. It was a normal day at the shtibel. I was giving a shtickel from the Sfas Emes before Minchah — I have a hosafah I just thought of this morning — remind me, Reb Nachum, to tell you later — and then we davened Minchah and lit the menorah. We were in the middle of Aleinu when I started to feel very tired.”

“Tired?” repeated my roommate.

“Yes, but not a normal tired. Like, my whole body mamash felt like lead; I pashut couldn’t move. I sat down in my chair and I noticed that everyone else in shul was also starting to sit down and put their heads down on the table, as if to take a shluff in the middle of davening!”

“And then?” my roommate prompted.

“That’s it. Next thing I knew, I was out cold. When I opened my eyes, the room was dark. From what I could tell, the entire shtibel — some twenty guys — all had their heads down on the tables, and I realized the menorah was gone. That’s when I called the police.”

“Everyone had fallen asleep?”

Reb Yoel was stroking his beard. “I can’t make any sense of it, Reb Nachum. By the time the police came, the minyan had woken up. The police called MADA to examine us. They said we all were healthy and fine.” He took another sip from his mug. “This coffee’s a mechayeh, by the way.”

“What time did the police arrive?”

“I’d say around 5:30.”

“I see. Now tell me more about the stolen menorah.”

“I don’t know so much about it, Reb Nachum. Dovid — Dovid Shtilerman — bought it a couple of years ago from a Judaica dealer that he knows.”

“Do you know the name of the dealer?”

“I wish I could remember. My memory’s not what it once was, Reb Nachum. It’s funny but I think both the first and last name started with the same letter.”

“What else can you tell us about the menorah?”

“The emes is that I don’t know so many more pratim about it. I do know it was very valuable.”

“Did it have any distinguishing features?”

Reb Yoel’s fingers were smoothing down his more-salt-than-pepper beard. “It had an interesting design. It kind of looked like the branches were stones, like one stacked on top of the other. Then the cups looked like little drops of water. Oh, and I should probably mention that there was a word engraved on the base.”

“A Hebrew word?” I noticed Nachum sitting up straighter in his chair.

“Yes,” said Reb Yoel, “on the base of the menorah was the word Nafshi.”

“Hmm…” was all my roommate replied. I watched him take a permanent marker from his shtender and slowly write the Hebrew letters nun-fey-shin-yud on his cast.

“You’ve been a huge help, Reb Yoel,” he said as he put the cap back on the marker. “Now let’s hear your hosafah on the Sfas Emes.”

The three of us schmoozed in learning for a bit before I walked Reb Yoel out of the dirah and headed to yeshivah. When I returned home, I could see the crouching backs of a bunch of cheder boys on our mirpesset. I came closer and noticed each boy had his own name card and mat, and that there was a plate of Krembos and a bottle of Shoko on our armchair.

Aside from the whirring of the dreidels, there was the silence of complete concentration.

“This is quite the chug,” I said to Nachum.

“Did I overdo it with the refreshments?” Nachum whispered to me, not looking away from the spinning dreidels.

“Nah, it’s a nice touch,” I reassured him.

“Ariel, lower your index finger a bit,” Nachum said to an orange-shirted boy in the corner. “Yes, that’s it. Excellent form.” The boy grinned up at him. “Avi, a little too much force,” he called to a kid with glasses. “Remember the soft twisting motion I showed you? Like you’re opening a bottle? That’s it. You got your gimmel!”

“Nachum,” I said, “I keep getting emails from mothers who want their sons to join your chug. Is there something you can do about that? There’s one mother who emailed five times today alone.” (I really hate it when people use our agency email address to send Nachum personal messages. For the record, he has a personal email address, and all shidduch résumés and any other messages unrelated to his detective work should please be sent to him there.)

“I’m sorry, Rosen. I had to cap the chug at eight. My eyes can track only eight moving dreidels at one time. If I accept more, it will compromise the quality of the instruction. Please relay that message to the mothers on my behalf.”

I left Nachum to his quality chug instruction, responded to a new batch of desperate parent emails, and updated our Substack. By the time I came back out, the boys had gone and it was time for candlelighting.

“Tonight we have two doughnuts — pistachio cream and apricot jelly filling — from Berman’s bakery.” Nachum held up a yellow box toward me. Suddenly, the tone of his voice changed. “Oh — I see you’ll be heading out after lighting, Rosen. A date with your shoel u’meishiv’s first cousin, I presume? I notice you’ve showered and even combed your hair. It looks less nest-like than usual.”

“Umm… thanks?”

“There’s still a couple of strands sticking up in the back, though. You might want to comb through again. Nice idea to go to the Galita chocolate factory. Don’t look so shocked, Rosen. The black letters on the tickets are so visible from behind the white of your shirt pocket, you’re practically a walking advertisement.”

Nachum put the box of doughnuts down on his shtender. “I’ll wait for you to try them, of course,” he said, “and I’ll chazzer Yevamos until you come back. Then we’ll start Kesubos together tonight.” If I didn’t know better, I’d say he sounded like he would miss me. We lit and sang, and I left him bent over his open Gemara.

When I returned two hours later (the chocolate was chalavi, the date was pareve), Nachum’s disappointment was gone. Two glowing eyes greeted me on our dark mirpesset.

I knew before Nachum even opened his mouth: “Rosen, we have quite the case on our hands. Eliad just called. The menorah thief struck again.”

Monday evening, December 15th, the second night of Chanukah

“HE struck again, Rosen,” Nachum repeated.

Nachum’s eyes were so bright he looked like he had just unwrapped a new Chanukah present. “This thief is creative, Rosen, and I admire a creative criminal. As I always say, if you’re going to break the law, at least do it with some originality.”

(It is statements like these that make me sing shirah that Nachum ended up on the side of the law-enforcers rather than the lawbreakers. One shudders to think what kind of criminal Nachum Sparks could have been….)

“It was the same MO as the Shtilerman theft,” Nachum continued. “This time, two adult males in a private residence. They fell asleep and woke up to find their menorah gone. I got these details from Eliad, but he’s sending the client over tomorrow morning. His name is Benny Butler.”

The next day, Nachum and I were finishing up Kesubos when we heard a knock at the door.

“That must be the client,” I said.

Nachum shook his head at me. “Surely you’ve lived in this dirah long enough to identify Mrs. Pessin by her knock.”

I opened the door and, indeed, our landlady was blinking up at me from behind her sparkly pink glasses.

“I have your whites washed and ironed, Nachum,” she called sweetly to my roommate behind me. “I’ll be down shortly with the colored clothing. And for both of you, I brought fresh soup.”

Two questions flashed in my brain simultaneously: One, since when did Mrs. Pessin do Nachum’s laundry and two, how could I get in on this arrangement?

“Thank you very much, Mrs. Pessin,” Nachum said. “I hope it’s your potato-leek soup. That one’s my favorite.” He gave her a huge, beaming smile that reminded me of his Rav Kav picture.

“Yes, it’s potato-leek,” she replied, looking pleased. “I made it especially with you in mind. I don’t know how you two manage with meal prep, and especially now that Nachum is out of commission.”

(I wouldn’t say Nachum helped very much when it came to food prep even when he had two working legs, but I managed to stop myself from saying so.)

“Where should I put the laundry?” Mrs. Pessin asked, moving into the center of the room. I glanced down wistfully at the crisply folded piles of white ironed shirts in her bag.

“The couch is great,” said Nachum.

“What is this line on the floor?” Mrs. Pessin abruptly wondered aloud.

“Hmm?” ventured my roommate.

“The glistening white trail?” She bent down on the speckled tiles, placing the laundry bag down beside her gold loafers. Her fingers began chipping at the tile.

Above her bent, be-sheiteled head, Nachum started to gesture at me frantically. “The box,” he mouthed. “Move the box.”

I looked at the direction of his pointing finger and saw a white box on the couch. I hastened to the couch to remove it but lost my footing and accidentally knocked it onto the floor.

Off fell the cover, revealing about fifteen brown snails and an array of green leaves.

“Nachum Sparks,” Mrs. Pessin said slowly, straightening up to her full four feet of height.

“Yes, Mrs. Pessin?” Nachum’s voice sounded oddly high-pitched.

“I thought I told you to never bring any more animals into the apartment.”

“Snails are technically not animals,” Nachum noted with a raised finger. “They’re gastropods.” Mrs. Pessin’s eyes narrowed into tiny, smoldering slits; Nachum’s finger fell fast.

“Let me make myself perfectly clear then. If it’s not a person and it’s either alive or was once alive, it cannot be in your apartment. Is that understood?”

“Yes, Mrs. Pessin,” Nachum’s bent head replied.

“Good. Now, Aryeh, help me get these gastropubs—”

“Pods,” coughed Nachum.

“Gastropods — whatever they’re called — out of here.”

I lifted the fugitives by their shells, trying not to be too grossed out by their slimy antennae, and tossed them back into the box.

“Can we keep them in the lobby?” Nachum asked quietly. “I’m actually in the middle of an important experiment.”

“Out.” Mrs. Pessin tapped her gold shoe. “O-U-T, out!”

Above her shouting, we suddenly heard a strident knock on the door.

A tall man in a maroon sweater poked his head in. “Is this the office of Detective Nachum Sparks?” I saw his eyes sweep skeptically over the scene.

“You must be a client,” said Mrs. Pessin, her voice magically restored to its typically sweet tenor. “I’ll leave you to your consultation then,” she said with a smile.

“Do you know you have a snail on your wall?” the man asked once Mrs. Pessin had left.

“Oh, sorry,” I said, hastily plucking it off and tossing it into the white box by the door. “Right this way.” I led him outside to our mirpesset, noting that his pointy black shoes seemed too sleek for the clutter-strewn path to his armchair.

“Welcome,” said Nachum, who had already wheeled himself out in front of us. My roommate gestured for the man to sit down. He did so, but only after making quite a show of vigorously dusting off the chair with his hand. (Granted, there were some Krembo crumbs left over from yesterday’s chug, but it still struck me as a bit more dramatic than was necessary.)

“You must be Benny Butler,” Nachum said amiably.

“Yes, yes,” he said with an impatient sort of sigh. “I’m Benny.”

“How can I help you then?”

Benny folded one leg over the other. “I hope you can help me. Eliad told me there was nowhere for me to go except 221 Rechov Ofeh, Knissah Bet — he said you’re the best detective agency in town. I wasn’t expecting to find two yeshivah guys in a dump.”

(Ouch. I’m not saying it couldn’t use a good cleaning, but “dump” seemed a little harsh to me. Behind his clasped fingers, though, my roommate was all amused smiles.)

“Eliad mentioned you have a unique way of solving crimes,” Benny continued. “He said you can look at me and know everything there is to know about me. How do you do it? Are you going to hold your Gemara up at me or something and read my mind?” There was no mistaking the jeer in his voice.

“I’m not going to hold up any sifrei kodesh,” Nachum said quietly, “but I am going to notice that you’re from Manhattan from the way you just pronounced the ‘r’ in the word Gemara. I’ll notice also that you’ve gotten a haircut this morning — there are loose hairs on your collar, but you recently showered, as your hair is still wet — so you’re a man with a flexible schedule. You work hard and have recently lost a bit of weight, attested to by the fact that the side seams of your pants have been taken in twice. You feel a lot of pressure to keep up your image: You’re wearing glasses, yet I can tell from the shape of your corneas that you’ve recently had Lasik surgery, so we can assume they are merely for aesthetic purposes. Your shirt and socks are both from Brooks Brothers, but the monogram on your cuff is “DB” — not “BB” as we would have expected. Why would a man who matches his socks and sweater down to the identical shade of red wear someone else’s shirt? I always say, where logic is absent, sentiment is present; we can deduce that the shirt is meaningful to you. As you clearly like to shop at Brooks Brothers, we can assume that you bought it for someone with the initials “DB” — you look too young to have a son your size, so we’ll guess it was a brother. Why did you never deliver the gift then, Benny? There must have been a falling ou—”

“Enough.” I jumped at the sound of Benny’s hand smashing down onto the shtender standing between him and Nachum. “I didn’t come here for therapy.”

“So why did you come?” Nachum asked softly.

“I want my menorah back.”

“What happened to it?” Nachum asked, leaning back in his wheelchair, his fingers intertwined under his chin.

“Didn’t Eliad tell you?”

“I’d like to hear the narrative firsthand.”

“Fine, I’ll tell it over quickly.”

“Quickly but thoroughly, please.”

Benny nodded in his impatient way. “I had arranged to do a private showing in my home of some of my newly acquired pieces.”

“How new?”

“Only a few days in my possession.”

“Created by a specific artist?”

“No, no, by a variety of artists, none of whom I know personally.”

“And you were showing these pieces of art to a longstanding client?”

“Yes, longstanding and very trusted.”

“His name?”

“Jared Fisher.”

“Was anyone else in the house?”

“No, my wife and kids were at her sister’s for a Chanukah party. I was supposed to join them after the meeting, but I never made it there.”

“Did anyone else come to the house that day?”

“We had a technician in the morning come to check a suspected gas leak. Oh, and my cleaning help, of course. We have a cleaning lady come every day.” Nachum nodded. “Among the pieces was a menorah. It’s a very special piece. It has this wine, grapevine motif that has always reminded me of those vineyards in the Golan Heights.”

“What time did Jared arrive?”

“Let’s see, it was right after I lit my own menorah. I’d say that was around 7.”

“And what happened after he came?”

“Almost as soon as he walked through the door, I started to feel very sleepy. I led Jared toward the items on display and next thing I knew, I was down on the floor. When I woke up, Jared was lying beside me, fast asleep. The grapevine menorah was gone from its glass case.”

“You called the police immediately, I presume?”

“Well, I looked around a little first. To make sure there wasn’t anyone else in the room.”

“And there wasn’t anyone?”

“Not that I could see.”

“Did you make a sale in the end?”

“Jared and I rescheduled.”

“I have two last questions for you, Benny.”

“Yes?”

“Were there any Hebrew letters on the base of the menorah?”

Benny’s eyebrows shot up in surprise. “Well, yes, as a matter of fact, there were. There was one Hebrew word engraved on the base.”

“And that word was?”

“Kadsho.”

Benny shifted restlessly in his chair as Nachum wrote the letters kuf, daled, shin, and vav onto his cast.

“Thank you, Benny. This meeting has been very” — there was a newspaper on Nachum’s shtender, and his eyes fell on the picture of the menorah on the cover — “illuminating. I’ll be in touch if there are any updates.”

“Please do. What was the second question?”

“Excuse me?”

“You said there were two last questions.”

Nachum smiled in a pleased sort of way that made me think Benny had passed a test Nachum had laid out for him. “Yes, yes. You remembered. The second question is whether you provided the newspaper with this picture of the menorah?”

Nachum held up the front cover. Under the headline “Menorah Heist in Jerusalem” was a picture of a silver menorah with grapevines running up and down its eight arms. “Did you give this picture to the press?”

Benny took the paper from Nachum’s hand with a surprising degree of force. “I’ve never seen that picture in my life. I’d very much like to know where it came from.”

After we escorted our client out, Nachum wheeled himself back out to the mirpesset. I watched him stare intently at the empty armchair for several silent moments, as if the particles of air hovering above the chair still contained the voice and form of our latest client.

At last, Nachum spoke to me. “You know I’ve been working hard on my mussar vaadim lately, Rosen. The ones on shviras hamiddos?”

I nodded.

“Well, as hard as I work, I can’t deny that I still feel angry — very angry, Rosen — when someone comes to me for help and then lies straight to my face.”

To be continued…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1089)

Oops! We could not locate your form.