Face-Off

| December 2, 2025He stood up to a pro-Hamas mob at a New Jersey shul. Who at the top is out to indict Moshe Glick?

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian, Family archives

Dr. Moshe Glick never dreamed that saving a fellow Jew from an Islamic assault in front of a New Jersey shul would land him on the defendant’s bench, especially when there was explicit video footage that the purported victim was clearly the attacker. In a case plagued with legal miscues, buried evidence and coaching of alleged witnesses, there was a clear agenda: Someone was determined to get that indictment

DR. Moshe Glick and his wife Renee were in the lobby of the Inbal Hotel in Jerusalem, having traveled from their home in West Orange, New Jersey, to participate in a chizuk mission to Israel, when the phone call came. It was Moshe’s lawyer on the line, and he had bad news.

“They’re going to press charges… you could be looking at five to ten years in prison.”

When you’re a law-abiding, upstanding citizen and a family man; a dentist who’s never threatened anyone with anything other than the occasional root canal for not flossing; a maggid shiur and pillar of chesed and community work, those are not the words you think you’ll ever hear.

Dr. Glick’s story, in which he protected a fellow Jew being assaulted during an unauthorized pro-Hamas demonstration outside a New Jersey shul, is just one act in an unfortunate script playing out in many Jewish communities around the world since October 7, as pro-Palestinian protestors have not only been threatening, but physically terrorizing Jewish communal institutions and individuals. Buoyed by the hand of Hashgachah and the groundswell of support they’ve been receiving, the Glicks are determined to see the story through to a happy end. And in the process, they’ve learned about a powerful yet much underused legal tool called the FACE (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances) Act — a federal law that makes it a crime to physically obstruct anyone trying to access health services or their place of worship — that can be used to protect Jewish communities in the United States.

Say Little, Do Much

The Jewish community in the MetroWest area of North Jersey, encompassing West Orange, Livingston, Millburn, and more in Essex, Morris, Sussex, Union, and parts of Somerset Counties, had always been active in its expressions of support for Israel, Jewish pride, and chesed, but the year following October 7, 2023 saw a tremendous upsurge in advocacy and activity.

Moshe and Renee Glick are at the center of a group called the MetroWest Israel Action Committee. As soon as the shock of the Simchas Torah pogrom was absorbed, they swung into motion. Together with other leaders like Larry Rein and Barbara Listhaus, they held events and rallies in support of Israel and Jews abroad. As early as the following Sunday, the group organized a 6,000-person march from one of the local shuls, ending with speeches and chizuk.

“We brought the message that, ‘Hey, we took a punch, but we’re going to come back fighting,’ ” Moshe says. Never did he dream that the battle would land him in court on false charges, facing years in prison for defending a Jew from assault in front of his own shul.

The Glicks have always been community doers. Their humility precludes them from sharing more, but some research yields an impressive list of klal activity, just a sampling of which includes founding the West Orange/Livingston Chesed Committee, which fills needs ranging from bikur cholim and Tomchei Shabbos to assistance finding employment and paying bills; and helping to start Kulanu, a chinuch program for unaffiliated families and kids who are no longer in a yeshivah environment.

Moshe and Renee are held in high esteem in the broader local community as well, and have formed warm relationships with police and elected leaders. They were part of a community initiative that helped block a one-sided resolution before the West Orange Township Council calling for a ceasefire in Gaza, and in advocating for the town’s adoption of the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism in January of 2023.

Pivotal Fair

It started with a simple conversation.

In early November 2024, Moshe was approached by Gedaliah Borvick, an American oleh and expert in Israeli real estate, about hosting an informational event about buying property in Israel. Borvick was running a series of similar programs around the Tristate area, at which attendees could meet a team of real estate professionals to learn about the options and process of buying a home in Israel. One was scheduled for nearby Bergenfield, and the Glicks readily agreed to host another one at their home in West Orange, scheduling it for November 13.

Then the warning signs began flashing.

Protesters and agitators had been plaguing numerous events in the area. Hundreds of pro-Hamas protesters had descended on the Bergenfield expo on November 7, shouting for intifada and spouting threatening and anti-Semitic slurs. “That evening came close to seeing violence, but Bergenfield police did a great job of keeping the sides separated,” Moshe says. A police report of the event sums up the agitators as “very aggressive, but not crossing over into violence.”

But threat of physical or bodily harm was real. The very same day, an anti-Israel protest in Amsterdam escalated into violence, leaving close to 30 people injured. And months earlier, Paul Kessler, a 69-year-old Jewish man, died from his injuries after being assaulted by protestors in Ventura County, near Los Angeles.

Next, the Glicks received a threatening letter. Their doorbell camera captured a woman (later identified as an activist using the name Terry Kay, who would play a major role in pro-Palestinian protests) dropping off a thick envelope on the porch. It included semi-official documents from well-funded organizations like American Muslims for Palestine (AMP) and the Palestinean Assembly for Liberation (PAL-AWDA NY/NJ/Ohio), warning the Glicks against holding a pro-Israel event in their home. In a gesture intended to intimidate, she also made it clear that she had pictures of their home.

These organizations had the event in their sights.

Gedaliah offered to cancel, but Moshe wouldn’t hear of it. Wishing to ensure there would be proper security protocols in place, he facilitated coordination between Thomas “Chip” Michaels, chief security officer of the Jewish Federation of Greater MetroWest New Jersey; the West Orange Police Department; and the Essex County Sherrif’s Department.

Chip’s team mined social media and determined that a group of protesters planned to meet several blocks from the Glick home on November 13 and march on the location.

After some discussion, it was decided to move the event to Ohr Torah, a shul in close proximity, of which Dr. Glick is a board member. Moshe paid for extra private security. The planned event was expanded to include an outdoor barbecue, with Tehillim, singing, divrei Torah from the local rabbanim, and an address by Eliezer Goldberg, who was in the shloshim mourning period following the death of his brother, Rabbi Avi Goldberg, an IDF reservist killed in Lebanon. The real estate fair would follow, indoors.

Another last-minute add-on was to arrange for Amir Goldstein, a videographer and owner of Creative Image Productions, and a friend of the family, who agreed to come and get some footage.

Moving the event out of their home seemed like a concession, and the Glicks weren’t too pleased. But the redrawn plans for the event as a result of the venue change would later prove to be pivotal in leveraging federal intervention.

Dr. Glick reached out to the deputy police chief of the WOPD to determine whether the anti-Israel protesters had a permit to march and where they would be allowed to protest. He was told that the protesters had not filed for a permit to march or assemble (as required by local ordinance), but that policy was to allow it as long as things stayed peaceful. Police assured him that safety was their number one priority.

Fateful Night

The event began, as planned, at about seven p.m. Moshe and some others were on site long before, working with the security team, which included Chip Michael’s people and a private security firm hired by the Glicks. There were also officers present from both the WOPD and the Essex County Sheriff’s office.

Meanwhile, as planned, between 75 and 100 demonstrators converged several blocks from the Glicks’ home and began to march toward it. At some point, they realized the event had been moved to the shul and made the decision to march there instead. Videos posted online by the marchers show them decked out in kaffiyehs, waving Palestinian flags and chanting slogans. They accosted the Jews they met on the way with verbal barbs — illegal in West Orange — such as, “Zionazis! How many babies did you kill today?” “You are Hitler!” and “Did you steal this house?”

When the group arrived near shul property, WOPD officers told them to stop. In publicly available bodycam footage, Police Sergeant (now Lieutenant) Brad Squires can be heard telling the group not to pass the property of the WOFD firehouse that neighbors the shul. In the recording, a protester clearly tells the others that “police want us to stop here.” One of the group responds, “We’re not stopping here, we’re not stopping this far away.”

Brushing police off, the demonstrators continued on toward the grassy slope leading to the shul’s parking lot. Chanting and hurling insults at the Jews gathered there for Tehillim and songs — and at the police — the protestors approached the grass. A choke point was formed at a gap between the bushes, just up the hill from the shul parking lot, and the two sides met.

On bodycam footage, police can be heard ordering the protesters back. “You’re making me nervous,” one of the officers says. But the protesters continue to ignore them, shouting and blowing vuvuzelas — incredibly loud airhorns, banned at some sporting venues for their ear-splitting volume, which can cause hearing damage. (The Justice Department would later identify the vuvuzelas as “weapons reasonably known to lead to permanent noise-induced hearing loss,” and define blowing them at close range as assault “to cause injury and intimidate.”)

Showdown

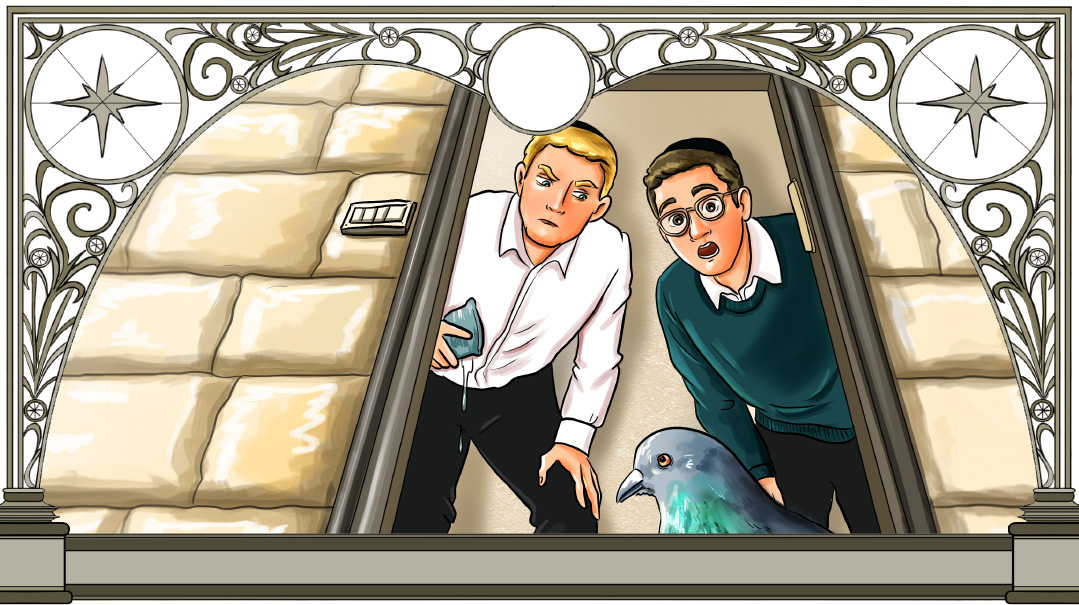

The key moments happened fast, and are all recorded on surveillance footage from the shul security cameras and footage shot by Amir Goldstein, the videographer.

A kaffiyeh-clad man, later identified as Altaf Sharif, approached a knot of people including Glick and David Silberberg, a 64-year-old man standing near him. Sharif blew his vuvuzela directly in Glick’s ear, who swatted it away with his hand. Sharif assumed a threatening posture and charged toward Glick “with intent to cause serious bodily harm,” according to the later DoJ complaint. Glick took a few steps back, while Silberberg pulled pepper spray from his pocket, squirted Sharif in the face, and put it back in his pocket. (Sharif would later tell police he was just trying to grab the pepper spray in self-defense and that his horn had been ripped out of his hand. But the video shows Silberberg stow the spray right away, and Sharif holding onto his horn throughout.)

Startled, Sharif stopped and rubbed his eyes. After a few moments, he asked one of the other protestors, “Who did that? Who sprayed me?” A man later identified as Eric Camins pointed at Silberberg and says, “The Jew is here.”

About ten seconds later, Sharif attacked. He grabbed the older and smaller Silberberg around the neck, applied a headlock, and tackled him, pulling him down the slope to the parking lot with his arm still locked around Silberberg’s neck. At the bottom, Sharif dragged Silberberg toward a parked boat and some sharp metal protrusions from a boat hitch.

From the moment of the initial attack, Glick can be heard on the video shouting, “Officer! Officer!” Police are nowhere to be found. “We didn’t see anything,” the bodycam records them later saying. Still shouting for police, Glick followed Sharif and Silberberg down the slope. He tried to push Sharif off the older man, but the enraged attacker was squeezing tightly.

Glick again called for police help, then realized he couldn’t afford to wait any longer. A trained Hatzolah EMT, he realized Silberberg’s airway was cut off and that he was losing consciousness. “I saw his knees buckle and realized I had to do something, now. I swung the flashlight I was carrying, once, at Sharif’s back.”

Glick aimed at Sharif’s back, but between Sharif’s constant motion and the mob surrounding him, the blow inadvertently struck Sharif in the head. Startled, he released Silberberg.

It was then that police finally arrived. They offered Sharif medical attention, or to rest against the police car, but he declined both offers. “Nah, I’m good, I just got a little surprised, that’s all,” he told police officer Lt. Wilfred Jiroux on camera. Other protesters shouted at the police, telling them to “leave him alone, he’s fine.” Picking up where he left off, Sharif went right back to shouting and blowing his vuvuzela. At this point, over blistering verbal abuse and antagonism, the police finally moved the noisy protest across the street and away from the shul.

Later, Sharif, who apparently reconsidered the strategic value of seeking medical attention, did visit with a first-aid crew at the firehouse. He was told he had no concussion and was treated for a superficial skin wound.

The rest of the evening continued relatively uneventfully — if masked, horn-blowing, slogan-shouting, insult-hurling, kaffiyeh-wearing protesters outside a shul can be considered par for the course.

Glick himself remained for the rest of the evening and served the police officers food from the barbeque. Police said nothing about the incident, and Glick went home considering the incident closed.

It was just beginning.

Alternate Reality

The first indication that something was amiss was an interview with Altaf Sharif that appeared five days later in Fight Back Better, a pro-Palestinian rag. Sharif described an alternate reality — one in which he was peacefully exercising his right to free speech when he was suddenly assaulted by a bunch of Jews, pepper sprayed, and whacked over the head just for the crime of wearing a kaffiyeh.

All indications were that Sharif’s narrative was not taken seriously outside of his own circles, and the Glicks, who were celebrating the wedding of their son, were able to do so without concern. Hashgachah spared them worry until two days after sheva brachos ended, when Moshe received a call from Detective Bryan Louis of the WOPD, asking him to come down to the local police station to answer some questions.

Moshe immediately retained Mitchell Liebowitz, a criminal lawyer and graduate of the Jewish Education Center/Rav Teitz Mesivta Academy in Elizabeth, which the Glick’s own children attended.

Recorded interviews conducted with Sharif and another protester, Matt Dragon, by Detective Louis are publicly available. Much of their statements in the recordings are clearly contradicted by police bodycam and Amir Goldstein’s footage.

Sharif claimed that the protesters were told they couldn’t stop in front of the firehouse for safety reasons and had to continue to the shul. But Dragon testified — and Sgt. Squires’ bodycam captured — police repeatedly telling the protestors to stop at the firehouse and not enter the shul’s property. The bodycam also captures the protestors reaching the decision to ignore the police and march toward the shul, and deriding Sgt. Squires.

In the footage, the Jews politely request of the police to move the protestors away and to set up barricades. But Sharif told Detective Louis that “the counter-protesters approached us… they stormed towards us, ran toward us.” Louis accepted his version unquestioningly, and even led Sharif on, asking who were the aggressors. “They came up to us, trying to fight us, super aggressive, our side was not like that at all.” Again, the footage clearly shows otherwise.

Sharif also told police that Silberberg and Glick tackled him while he was trying to grab the pepper spray, and “I tried to defend myself while hunched over.” In the video, he can be seen charging at Glick and tackling Silberberg, pulling him down the hill, although the spray is already back in Silberberg’s pocket.

Liebowitz arranged a meeting with a West Orange police detective and provided him with the video evidence plainly showing that Sharif was the aggressor. An Essex County assistant prosecutor would ultimately be responsible for the decision to file charges in the case, and the detective gave assurances that he would forward the footage to him.

The drama didn’t deter the Glicks from their dedication to communal service. In January of 2025, they joined an Israel365 mission to the Holy Land, viewing the Nova massacre site firsthand and visiting with bereaved parents. After the mission, the Glicks spent time with injured soldiers at Sheba Hospital, bringing needed supplies and gifts, and sharing chizuk with the Chevron community. They were just checking in at the Inbal Hotel in Yerushalayim on January 17 when a member of his legal team back home called with an update. “Moshe, you’re not going to believe this,” he said. “The county is going to go ahead and press four counts of criminal charges against you.”

Moshe describes what it was like to receive the shocking news. “All of a sudden, everything just stops,” he says. “I could be looking at serious years in prison, loss of my dental license — my parnassah — and all my nonprofit activities. I still couldn’t believe this was real, I was pretty shaken.”

And the charges weren’t small misdemeanors, but felonies. Someone at Essex County had really decided to throw the book at him.

The “good news” was that at least he wasn’t going to be arrested at the airport. Essex County would allow him to turn himself in peacefully.

Understandably stunned, Moshe did his best to put on a brave face for the rest of the mission, and took advantage of his proximity to the Kosel to daven.

Just two days later, he saw the first “Divine wink,” one of just many instances of Hashgachah pratis that he would see as the ordeal continued.

As a gabbai in his shul back home, Moshe hadn’t received an aliyah for four years (other than the tochachah). On the Shabbos after the phone call, he was davening in a small shul in Yemin Moshe, and as there was no Kohein, he was given the first aliyah. He was stunned to read words (that he had never been oleh to before) in parshas Mikeitz describing Yosef’s release from prison. “I couldn’t believe it,” he remembers. “It was a real hug from Hashem. It’s like he was telling me everything was going to be okay.”

Upon returning home, Moshe presented himself to the police, subjected himself to fingerprinting and a mugshot, and was released home pending a grand jury indictment hearing.

His legal team was astonished. How had Essex County decided to prosecute when there was clear video evidence that Moshe had been defending an innocent man, not assaulting one; and that the purported victim was clearly the attacker? It was just the first sign of obvious prejudice that would appear as the case unfolded.

While the legal team got to work setting up a meeting with the Essex County Prosecutor, Moshe and his family were advised to keep silent on the case. As the media circus grew, he confided only in a few rabbanim, including Rabbi Eliezer Zwickler and Rabbi Zalman Grossbaum, as well as Rabbi Elie Mischel of Israel365, who were a steady source of strength; as well as a small team of confidantes and advisors.

The Ugly Side of Things

The other side, however, was not interested in silence. Following an incident of pro-Palestinian violence against Jews in Boro Park on February 19, the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) put out a press release on Moshe’s case, hoping to counter their own bad press and depict themselves as victims.

The press picked up CAIR’s release, and the Glicks were bombarded by reporters. The family, the Silberbergs, and Moshe’s dental office had their details published online and became the subject of doxxing attacks. “I feel bad for my staff. They were kept busy answering phone calls like, ‘Do you know you work for a terrorist?’ or ‘Does he first knock out their teeth and then replace them with implants?’”

The Glicks themselves maintained silence, with the rabbanim speaking out forcefully on their behalf to the community; but it was a tough, painful period.

Shortly after the CAIR press release, Moshe was called to the Torah for another aliyah, his second since the case began. Again, there was a special message for him, another hug: In the sixth aliyah of Shemos, Hashem reassures Moshe that although he struck the enemy, he has nothing to fear, “ki meisu kol ha’anashim hamevakshim es nafsehcha — because all those pursuing you have died.”

Just before Pesach, Moshe’s lawyers were finally able to meet with the Essex County assistant prosecutor.

Now the mystery of how the case had come so far was finally solved.

The assistant prosecutor had never seen the video footage documenting the actual events. Bryan Louis, the WOPD detective who had forwarded the case to him, had withheld the key evidence. In the taped interview he conducted with Sharif, Louis actually leads him on, asking, “Why do you think this happened to you?” prompting Sharif to answer that he could only be identified by his kaffiyeh (never mind the fact that he had someone in a chokehold), and the other side “was clearly out to get someone that night… they saw us as a threat.”

Louis digs further, apparently trying to get to a bias charge. “ ‘As us,’ what would you describe ‘us’ as?” he asks, coaxing Sharif to blame it on Islamophobia and Arab hate.

Louis is one of several officers facing internal affairs complaints filed by the Glicks for bias and misconduct, among other charges.

Now, when the assistant prosecutor finally saw the footage, he was immediately receptive to Mr. Liebowitz’s presentation and recommended to his supervisors that the charges be dropped. As Pesach approached, the Glicks had high hopes that the case would go no further.

Their positivity proved premature.

The video presentation to the assistant prosecutor by Moshe’s defense counsel notwithstanding, the prosecution against Moshe continued unabated. He in turn took up the gauntlet, flipping from seeing the facts Dr. Glick’s way to devoting intensive energy and numerous hours to prosecute him.

“At this point, we realized something was really going on,” Moshe says. “We weren’t just up against a mistake. There was powerful political pressure coming from someone way up the ladder to get me. There’s no way this series of inexplicable decisions was a coincidence.”

Saving Face

Moshe added Mike Bachner, another JEC graduate and experienced criminal trial lawyer, to the team. More meetings were held with officials in the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office, who began pressing for a compromise of sorts that would give them a win.

They offered a plea deal, under which Glick could avoid trial and prison time, submitting instead to Pretrial Intervention (PTI), which entailed weekly counseling sessions for a year (six months for good behavior). The prosecutors had already dropped the second-degree bias intimidation charge, which is the most severe — carrying prison time even for first-time offenders. The remaining charges were only lesser felonies for which he could take PTI without a guilty plea. Upon successful completion of PTI, all charges against him would be dismissed, and he could most likely have his record wiped clean.

Were he to refuse PTI, though, he was liable to face a grand jury indictment.

“This was’t a decision to be made lightly,” Moshe explains. “PTI was tempting. I could make everything go away, have my record clean, and put a halt to the mounting legal fees.” But he refused.

“I just couldn’t live with myself if I gave into this,” he explains. “They can’t be allowed to attack Jews and cast themselves as the victim. What would happen the next time? When someone else needs to be saved, will a bystander hesitate to act because they don’t want to get in trouble? This could cost lives.”

The Glicks decided to go to grand jury. In the meantime, the askanus machines got cranking. “We worked every contact we had,” Moshe says. “We asked for a meeting with New Jersey Attorney General Matt Platkin, but it was denied. Over one hundred rabbanim from Lakewood and across New Jersey, including the RCA and Chabad, signed a letter for us.”

A rally was held in June on the steps of the county courthouse in Newark, bringing together speakers and influencers from a range of backgrounds to garner support.

Moshe also prepared to testify before the grand jury. While he knew he’d be up against a hostile jury, he was hopeful that the evidence was clear-cut enough for him to win. He didn’t realize that he never had a chance.

“Most people have never appeared before a grand jury,” Moshe says. “Let me advise you: Don’t! They kick you around and string you along. You have no chance.”

Grand juries are the playground of prosecutors’ offices, with little oversight and less accountability. New York Chief Judge Sol Wachtler coined a phrase common in legal circles: “A grand jury will indict a ham sandwich.”

On June 25, Moshe showed up for his 9 a.m. appearance on the tenth floor of the Essex County Criminal Court in Newark, New Jersey. He was delayed until 12 p.m., when he was finally invited to enter.

Entering the court, it wasn’t hard to see which way the winds were blowing. The grand jurors weren’t listening to him, refused to look at him, and weren’t engaging at all. The room was filled with prosecutors and police, but he wasn’t even allowed to bring his lawyer. He showed the videos and presented the proof, but to no avail.

Oddly, Logan Teisch, the prosecutor representing Essex County, called an investigator with the Prosecutor’s office to the stand a second time following Moshe’s presentation, ostensibly to refute his words — a rare step in grand jury proceedings. The prosecutors really wanted this indictment — further signs that they were under heavy pressure from someone.

The proceedings were plagued with legal miscues. Among others, Teisch disqualified a potential juror at the grand jury proceeding without a judge’s decision, a clearly illegal move. That alone was reason for the indictment to be voided.

But there was an agenda here against Dr. Glick and what he represented, and someone was determined to get that indictment.

They got it.

Turnabout

“That night was my lowest point,” Moshe says, until the Hand of Hashgachah showed itself again.

The grand jury had been a last hope, and it was a total bust. The system reeked of anti-Semitism and was against him. It had been clear early on that there was no one to talk to at the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office, and now the grand jury had failed him.

At this point, the assistant prosecutor again pressed the state’s offer of PTI without admission of guilt.

Friends, family, and Dr. Glick’s close advisors urged him to accept the deal. You fought the good fight, they argued. Costs had climbed to well into the six figures and innumerable hours, and would still go higher. Let them have their little “win” and move on, they argued, while you focus on other important initiatives to help the community.

Still, Moshe struggled. “I didn’t like the feeling of it,” he says. “Where’s our civil rights? A Yid gets assaulted in front of a shul, and we’re supposed to just give up and give in, let them win? What kind of message does that send to the Jewish community? And even more importantly, what message does that send to those who target Jews and our shuls? What kind of precedent does that set for next time?”

Still, he was close to caving, when the phone rang. “[Assistant Attorney General] Harmeet Dhillon is working on your case,” the caller said. Another call the same night corroborated the first. The Trump Administration’s Department of Justice was about to wade into the fight.

Encouraged, Moshe held on, and the legal team got back to work, filing a 30-page motion to dismiss the indictment based on procedural errors. The prosecutor’s office readily admitted the indictment was flawed and indicated that they planned to abandon it. The primary reason? The arbitrary dismissal of a fully qualified juror from the grand jury, contrary to law.

But the prosecutors weren’t dropping the case. Just before Succos, they filed for a second, superseding indictment to absolve the errors in the first. Moshe and his team weren’t even notified, or invited to testify, at this one, which passed easily.

Constant Reminders

The Justice Department plainly saw the facts in the case as the Glicks did, and filed civil cases against six of the pro-Palestinian protesters for violations of the FACE Act. The law, designed to prevent protesters from blocking access to clinics, also criminalizes blocking houses of worship.

Harmeet Dhillon held a press conference in which she detailed DoJ complaints brought against Altaf Sharif, Eric Camins, Matt Dragon, Terry Kay, and two others. She indicated that she wasn’t ruling out criminal charges against them.

It was encouraging that the DoJ clearly agreed as to who the aggressors were that evening, lending strong support and backing to Dr. Glick’s case in defense of the charges against him.

Following the DoJ announcement, Moshe got another aliyah in shul. “It’s constant chizuk, constant reminders to have faith,” Moshe says. This one was chamishi of Ha’azinu, which speaks of the foolishness of Klal Yisrael’s persecutors and their ultimate demise at the Hands of Hashem.

The Good Fight

Buoyed by the DoJ and in light of the clear discrimination and obfuscation against him, Dr. Glick and his legal team are going on offense, bringing complaints and filing motions on a number of fronts.

Moshe’s team asked federal court to block the Essex County Prosecutor’s case due to evident anti-Semitic animus. That motion was denied on a technicality, but can be filed again.

A notice preserving the right to sue for up to $9 million was filed against the West Orange police officers.

A police Internal Affairs complaint has been filed against Detective Bryan Louis, for failing to forward exculpatory evidence to the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office, selective enforcement, witness coaching, and subordination of false testimony by leading Sharif in his statement to indicate that he was an innocent victim attacked for “Islamophobia,” among other charges.

Internal Affairs complaints have been filed against a police lieutenant, Bradley Squires, for a series of missteps at the scene of the assault, including: turning off his body camera (violation of NJ Attorney General guidelines), admitted conflict of interest, relying on biased account, making an early and baseless determination of guilt on the spot despite seeing nothing, failure to arrest protestors in severe violation of clear warnings, and — most egregious — failure to intervene with violent assault which forced Dr. Glick to take action.

While things are looking up, the case is still pending and Glick remains under indictment, although his lawyers will be filing challenges to the validity of the second indictment as well. Should the indictment hold up, he will be facing arraignment and trial. PTI is still an option, and had Moshe taken it when it was first offered, he could likely have been done already. But he views this as a fight for Klal Yisrael.

He’s grateful for all the support he’s received from the community. “The other side has bottomless pockets and highly paid lawyers. So often it has felt like us against an army,” he says, citing gratefully the assistance he’s received from organizations like Agudah of NJ, JBAR, The Lawfare Project, and Israel365, which raised significant sums of money to help cover some of the legal expenses.

He’s had to dig deep into his spiritual resources to keep going, and he candidly shares that it’s not simple. “It’s easy to have emunah and bitachon when things are going smoothly,” he reflects. “It’s when the challenges mount upon us that we’re called upon to lean into our faith and trust. Emunah is not only for the guy who missed the plane that crashed, but for the guy who was on standby and actually got onto that flight.

“Being arrested and threatened with incarceration is a major test. I’ve learned so much from Rabbi Efrem Goldberg’s incredible Living with Emunah series, including that when Hashem tells Moshe, ‘No man can see Me and live,’ it can be understood as an explanation that we cannot know the Heavenly calculations for our benefit during the darkest of times.”

The Glicks have learned a new appreciation for the shared bond between all members of Klal Yisrael, and our existential reliance on each other and ourselves. “Im ein ani li mi li… we have to look past our differences to focus on our unity, or our enemies will force us to do so.” —

Face the Law

The FACE (Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances) Act of 1994 is a federal law that makes it a federal crime to use or threaten force, or physically obstruct, anyone who is trying to access certain health services or exercise their right to religious freedom at a place of worship.

The Act is a useful tool to deter aggression at rallies or marches, and to later potential criminal charges or civil lawsuits against agitators and protesters. Department of Justice lawyers are researching whether violations occurred at the Israel real estate fair in Livingston, New Jersey. The recent demonstration in front of Park East Synagogue in Manhattan, during which protesters blocked the shul doors, is also being examined.

Several elements need to be in place for a FACE Act violation to be incurred:

- Prohibited conduct: there must be either the threat or use of force, harassment, intimidation, physical obstruction or damage, or recording someone without consent

- Target and intent: that activity must intentionally be targeting a person or facility seeking or providing religious worship

- Religious element: the event obstructed must have a religious element to it

- Punishment: The law authorizes a range of repercussions to violators:

- The U.S. Attorney General can seek criminal penalties, including fines and imprisonment;

- The DoJ can pursue or civil remedies, such as injunctions, compensatory damages, and civil penalties;

Individuals who are harmed can also bring their own civil lawsuits.

“The implications throughout the country are enormous,” Dr. Glick stresses, advising anyone planning a rally or march to FACE-proof it. “The next time someone wants to violently protest in front of a Chabad house on a campus, a shul, a yeshivah or school, they’re going to think twice, because there are going to be serious ramifications.” He intends to hold seminars educating people how to make use of the FACE Act.

WHAT THE CHARGE SHEET LOOKS LIKE

Felony Aggravated Assault, Third Degree:

for allegedly attacking Altaf Sharif with a flashlight, state prison 3–5 years (unlikely for first-time offender), $15,000 fine

Felony Bias Intimidation, Second Degree (most serious charge):

for allegedly assaulting Sharif in the basis of his Muslim faith, state prison 5–10 years (even for first-time offender), fine up to $150,000

Felony Possession of a Weapon for Unlawful Purpose:

for carrying a 6-inch flashlight, state prison 3–5 years, fine up to $15,000

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1089)

Oops! We could not locate your form.