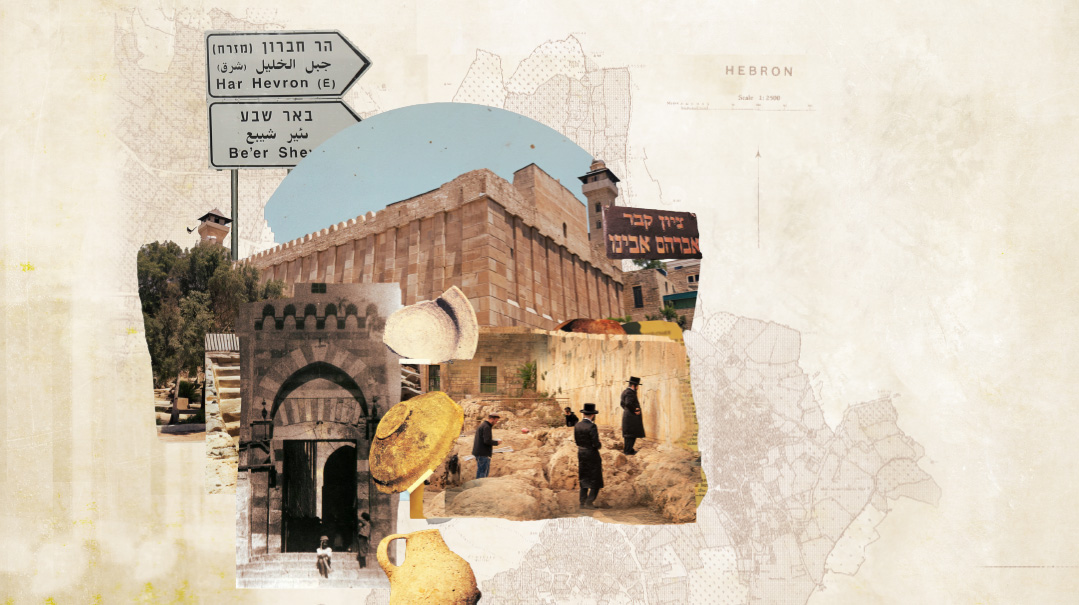

Secret of the Caves

For centuries the sacred caverns beneath Mearas Hamachpeilah were off-limits. These few found a way in

For 700 years, no Jew had entered the sacred caverns beneath Mearas Hamachpeilah. From a daring 13-year-old’s secret descent in 1968 to Noam Arnon’s midnight mission years later, generations risked everything to uncover what lies beneath the resting place of the Avos and Imahos

Chevron.

Chol Hamoed Succos, 1968.

Close to midnight.

The city is under curfew.

Just that afternoon, a terrorist had thrown a grenade at Jewish worshippers in the city, injuring 40.

A car pulls up outside Mearas Hamachpeilah, and a man and a girl wrapped in blankets emerge.

The man is Yehuda Arbel, head of the Shin Bet’s Jerusalem portfolio. And the girl is his 13-year-old daughter, Michal.

They’re there on a mission: to sneak inside the ancient stone building we associate with Mearas Hamachpeilah and explore what lies beneath its surface.

Eyewitness Accounts

From when the Mamluks conquered Eretz Yisrael in 1279, until Israel won the territory in the Six Day War in 1967, only Muslims were allowed to enter that tall Herodian-era building believed to be covering Mearas Hamachpeilah. Jews were restricted to praying up to the seventh step outside the entrance to the building’s eastern side. Even now, the Waqf control 81 percent of the building, and while Jews have access to the presumed tombs of Avraham and Sarah and Yaakov and Leah, they’re only allowed into Yitzchak and Rivka’s burial place ten days a year.

If access to the site has been banned for non-Muslims for close to 700 years, how do we know what lies underneath the ancient structure?

No exhaustive study of the site has been able to be conducted for risk of antagonizing the world’s Muslim population, but Noam Arnon, who spent eight years writing a 600-page doctoral thesis on Chevron and Mearas Hamachpeilah explains that although we don’t have actual tombstones inscribed with the names of the Avos, “When we weigh all the evidence — archaeological, historical, traditional; accounts of travelers, Biblical sources, and topography — it all points to the same conclusion.” The conclusion: This is it, the holy site where Adam and Chavah and our Avos and Imahos are buried, the place the Zohar tells us is the portal to Gan Eden, where all tefillos pass through on their way upward.

Throughout history there were some, a select few, who managed to make it not only inside the mosque, but also to the caverns underneath it and record what they saw, providing testimony to what lies below.

“The Talmud tells of Rabbi Bana’ah, an Amora, who managed to enter Mearas Hamachpeilah, but only the outer chamber,” says Arnon, who today is the spokesperson for the Jewish community of Chevron.

“The entrance to the cave is located on the floor of the mosque in what’s known as Yitzchak’s hall. There’s a flower-shaped marble structure over it that has a small, circular opening in its center and is covered by a copper lid.

“Jewish legend has it that about 400 years ago, when a visiting pasha toured the site, he leaned over to look inside that opening, his jeweled saber fell into the cave below. He ordered his servants to retrieve it, but anyone who entered died instantly. The pasha commanded the Jewish community to retrieve the sword, threatening severe retribution if they refused.

“No one dared to volunteer — except the great kabbalist Rabbi Avraham Azulai, author of Chesed L’Avraham and grandfather of the Chida. He entered the cave to retrieve the sword and managed to exit safely, but shortly afterward, on 21 Cheshvan, 1643, on the eve of parshas Chayei Sarah, his soul departed This World. He was buried in the ancient cemetery of Chevron.”

On August 25, 1859, Italian archaeologist and engineer Ermete Pierotti, aided by Muslim friends, tried to descend into the cave’s depths, but after descending only five steps, the Waqf guards pulled him back up. “The blows I received and the curses I heard did not diminish the great satisfaction I felt then and still feel today,” Pierotti wrote in his journal. “I can say that I saw something of the cave — ossuaries in white stone… a rock wall separating the lower and upper caves.’ ”

Archaeologists who attempted to study the cave, such as the British Ernest Mackay and the French Louis-Hugues Vincent, described the 2,000-year-old structure built above ground in great detail, but were unable to explore the spaces beneath it.

Another recorded visit was made by British Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, an officer in General Allenby’s command during World War I. After the British captured Chevron in the fall of 1917, Meinertzhagen entered the site through an entrance in the southwestern part of the structure, to ensure that enemy forces weren’t hiding there. He found a slightly open door and a narrow passage leading to “an underground hiding place containing, among other things, a large rock block surrounded by four pillars with flat tops and winding grooves.”

The next documented visit after them, in 1933, was made by a young British Zionist activist named Jack (Yaakov) Sklan. But he didn’t reveal that visit for nearly 80 years, until 2012, when his daughter, Yehudit, who lives in the yishuv of Ofra, arranged for Arnon to meet with Sklan and give his testimony. “He was then 97 years old, but completely lucid, with an exceptional memory,” says Arnon. “He described in great detail how, accompanied by a British officer, he descended three levels into an underground hall deep within the earth, where he found another door.

“Through this door, they descended a few more steps and then reached a barred window overlooking an underground hall. Sklan recounted that it was a fairly large hall, built of stone or natural rock. In the dim light, he saw tombstones. His Muslim escort explained that these were the graves of the Patriarchs.

“We scheduled another meeting to show Sklan diagrams and pictures in an attempt to pinpoint the locations he described, but on the eve of our second meeting, I received a phone call from his daughter — Sklan had been struck and killed by a jeep while leaving the Great Synagogue in Jerusalem after Shabbos prayers.”

A similar account was given to Arnon by an elderly man named Aryeh Ariel. Ariel told him that as a nine-year-old child, he accompanied his father on a trip to Chevron after the 1929 riots, where they joined a group of British archaeologists exploring the underground spaces beneath the building.

“We went down the stairs,” Ariel recounted, “and I remember them saying: ‘These are the graves of the Patriarchs.’ ”

A Young Girl Descends

A major breakthrough in knowledge came through the Arbels, after Moshe Dayan, the minister of defense, summoned Yehuda Arbel to his office shortly after the Six Day War. At the time, Israelis were settling in the remnants of the ancient Jewish community. Of course, they wanted access to Mearas Hamachpeilah, but the Waqf custodians were adamantly against non-Muslims setting foot in the mosque built over it. “I don’t want a religious war,” Dayan told Arbel. “We need a solution.”

Arbel, a bit of an archaeology buff, had the idea that if he could find another entrance to the caves below that didn’t require going through the mosque, he will have solved the problem.

“First, we needed to determine the direction of the cave below to understand where to dig from the outside,” Arbel wrote in his memoir. “I went on a site inspection and met with the Muslim custodian of the mosque, Sheikh Ataf, who showed me the circular opening on the western side of the mosque through which one could look down to the caves below.”

The sheikh told Arbel that when he was a child, his father — who was also the mosque’s custodian — would lower him through the very narrow circular opening into the cave below to “clean up the papers.” The papers were prayer notes and requests that Muslim worshippers threw inside, along with coins and banknotes, in an attempt to effect a “yeshuah” for their problems.

How could Arbel access this opening and map out the direction of the caves without starting a riot?

The moment arrived on the second day of Succos, 1968, when a curfew was imposed on Chevron in the wake of the grenade attack, and the mosque was closed. “I knew this might be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore the cave,” Arbel wrote. “I asked my wife whether she thought our daughter Michal would agree to descend through a narrow hole into a dark cave. Her response was immediate. She said that Michal wouldn’t just agree — she would be thrilled.”

“I was an adventurous child,” Michal recalled in an interview with Haaretz in 2006, conducted, ironically, in light of the fact she grew up to become a left-leaning literature professor who parted ways with her parents’ right-wing secular Zionism and regretted her foray into Mearas Hamachpeilah, feeling it was an affront to the Muslims. “I loved reading mysteries. When my mother asked me if I wanted to descend into Mearat Hamachpeilah, I treated her request with adventurous excitement. I didn’t feel afraid of the mission at all.”

That afternoon, her father prepared 13-year-old Michal for the task. She was shown how to take photographs and sketch architectural spaces, determine directions using a compass, and write a report. “After the exhausting training, Michal went to sleep, with the promise that I would wake her up at night,” wrote Yehuda Arbel.

That evening, he called Rehavam Ze’evi HY”d, the regional military commander. “I informed him that I needed to carry out a secret mission in the cave and requested special arrangements: the removal of guards from the area and assistance from the deputy governor. I then gathered a few ‘specialists’ and the necessary equipment for 10 p.m.,” wrote Arbel.

“A few hours after I went to sleep, my father woke me up,” Michal recalled in her 2006 interview. “I got dressed and got into the car. Inside, I wrapped myself in a blanket up to my head, looking like a bundled package. We drove to Chevron. We stopped for a while at the police station and then continued to Mearas Hamachpeilah. I emerged, still wrapped in the blanket, and entered the mosque.”

“We managed to squeeze her through the hole, which had a diameter of 28 centimeters,” Arbel wrote. “The descent went smoothly. The only concern that gnawed at me was that there might be no air down there, and if she fainted, we wouldn’t be able to help her. So I gave her matches and a candle to test the air.”

Once it was determined there was oxygen in the caves below, Michal began exploring. She recalls, “I was inside a square-shaped underground room. In front of me to the west were three tombstones, the middle one taller than the other two. On the opposite wall, there was a small square opening. They released more rope, and I crawled into the opening. I walked through a narrow, low corridor with rock-hewn walls. At the end, I found a staircase leading downward, but it ended in a solid wall.”

Arbel wrote, “We could no longer hear her voice, but from the rope being pulled after her, I estimated that she’d advanced about 20 meters. A few minutes later, which felt like an eternity, Michal returned and reported that the corridor ended in stairs leading upward and terminating in a sort of small platform. Above her head, she saw iron hooks holding a large stone.”

Michal then began measuring the area. “I measured the room: six steps long and five steps wide. Each tombstone was one step wide, and the space between them was also one step. The corridor was one step wide and about one meter high,” she noted. The low corridor was 34 steps long.

“When I counted the stairs, I noticed something strange: When I descended, there were 16 steps. But when I climbed back up, there were only 15. I counted them five times, going up and down, and got the same results each time. I climbed back up, received a camera, and went down again to take pictures of the room, the tombstones, the corridor, and the stairs. I went back up again, received paper and a pencil, and drew a map of the area. They pulled me back up, but the flashlight fell, so I had to go down and climb back up again. That was my final descent for the night.” It was already three in the morning.

Excited, Yehuda Arbel sent the films Michal had taken for development and printing that very night. In the morning, when Moshe Dayan arrived by helicopter for a tour of Chevron, Arbel approached him and presented him with the photographs and sketches. They proved beyond doubt that a tunnel ran beneath Isaac’s Hall, leading to another opening on the eastern side of the building. Michal descended into the cave twice more, and each time she emerged with new discoveries. She was so brave, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan asked to meet her.

“He asked me, ‘Weren’t you afraid of snakes and scorpions?’ ” Michal recalls. “I replied no, reminding him that I had a flashlight. We were a family that traveled a lot and visited many caves,” she notes. “At the time, it just seemed like an incredible adventure. Ten days after the first descent, I descended into the cave again, in the same manner.”

The third descent occurred a few weeks later. Similar to the first time, an IDF-built position near the Cave of the Patriarchs had been blown up. The position was unmanned, but an Arab child was killed, and two adult Arabs were injured, and the city was once again put on lockdown and the mosque closed.

“This time, they only asked me to remove the decorated tombstone from its place,” Michal describes, “because, according to my assessment, this tombstone blocked further passage to additional caves or another small chamber. But despite my efforts, the tombstone wouldn’t budge.”

The mysteries of the cave continued to intrigue the country’s leadership. Another secret mission to descend into the cave was organized in the month of Adar 5733/ February 1973. The operation was named “Operation Adar” and was initiated by Rehavam Ze’evi, then the commander of the Central Command.

Lieutenant Avner Tzadok, a reservist officer in the Armored Corps, was chosen for the mission due to his petite physique. He underwent a preliminary test, in which he was summoned to a military base and asked to crawl through a metal pipe with the same diameter as the entrance to the Cave of the Patriarchs. He then received training in photography, and on the appointed night, the night of 11 Adar, was lowered into opening. Tzadok safely entered, additional photography equipment was lowered after him, and he explored every underground space he could access and documented them, but the findings remain classified to this day.

Midnight Deception

The next time Jews secretly entered the Cave of the Patriarchs was in Elul 5741 (1981). Noam Arnon was privileged to lead the mission. “This mission was organized this time by members of Midreshet Chevron, where I learned,” recalls Arnon. “The goal was to open the stone Michal Arbel hadn’t been able to move and see if that could lead us further into the caves. We could not, of course, enter the same way that Michal entered, via the small circular entrance. However, she’d related that she’d climbed stairs that were blocked off by a stone. Where could that stone be? We measured the distance she had spoken of and revealed that the stone was on the other side of the Yitzchak hall, covered by Arab prayer rugs. The area was in the Arab-controlled section. How could we succeed in moving that stone, thereby allowing us to descend into the caves?

“We found the answer during Elul, when we were given authorization to say Selichos in Mearas Hamachpeilah every evening at midnight. The Arab guards left their posts to sleep. When we saw this happening night after night, we decided to smuggle in hammers and chisels. A backup team began singing and dancing during Selichos, drumming loudly to mask the noises we made. We lifted up layers of prayer mats and discovered the stone Michal Arbel had seen. It was held in place by metal bars. We began hammering on the rock with the chisels, and after a while it began to move.

“It’s difficult to describe the emotions we felt when we saw the stone move and reveal the opening under it. We entered, our hearts pounding with excitement. We found stairs that led down into the darkness and descended slowly. After the stairs, there was a narrow, dark corridor. We crawled through the corridor, using flashlights to guide our way. We reached the circular room Michal described and looked around. On the wall were three stones, but no cave was visible. Where was the cave? Were all our efforts in vain?

“Several minutes later an additional mystery presented itself. We felt a breeze from below. How could this be? Examining the ground, we saw several stones stuck together. The wind was coming from the gaps from between them. We slowly lifted up all those heavy stones to reveal a cave underneath.

“We went deep into the cave, and then it became clear: This was indeed Mearas Hamachpeilah, composed of two caves, one inside the other, of the ‘double shaft tomb’ type characteristic of the period of the Avos.”

“The first cave was larger, filled with earth almost to the ceiling, and from it, a narrow corridor led to a second, smaller cave. There were bones and pieces of pottery scattered on the floor, which we collected.

“The sounds of our hearts pounding was audible. No living being had been this close to the Avos in thousands of years. Each one of us spent some time considering the significance of being here. We tried with all our might to overcome our excitement, seize the rare moment, and focus on tefillah. After all, such an opportunity does not come every day, especially not on the eve of Rosh Hashanah!

“Hours passed, which felt like minutes. Before dawn, we received a message over our radio: ‘It’s almost dawn, you must leave now before the Arabs wake up and discover what happened during the night.’ We left the cave, overwhelmed with excitement and an uplifting, unforgettable experience.”

The four pottery vessels they took from the site were examined by Dr. Ze’ev Yavin, the chief archaeology officer of Judea and Samaria at the time, and were determined to be from the tekufah of the First Beis Hamikdash.

“Years have passed since then,” says Arnon. “We never had another opportunity to return to Mearas Hamachpeilah, but the experience and memories remain alive in our hearts.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 968)

Oops! We could not locate your form.