One Jump Ahead

| October 15, 2025“What’s the point in living like this, immobile and in constant pain? Why didn’t You just finish me off?”

By Yitzchak Landa, based on an interview with Cadet Boaz Abramoff, USAFA

You could say that military service was in my blood, but I never expected my blood to be in the service so soon.

I guess it’s good that I don’t remember anything from that day — or the day before, or several months that followed.

I don’t remember taking off or jumping out of the plane. I don’t remember the parachute failing, or spinning out of control, passing out, or striking the ground at the speed of a freight train.

I wasn’t in the plane where the pilots were frantically calling ambulances, and I wasn’t in the car with the nurse who saw me fall as she immediately pulled over, ran through the cactus fields, and saved my life.

I don’t remember being rushed to the hospital or into surgeries, my parents, friends, or rabbi visiting me during those early days, or the grim prognosis the doctors gave for my survival and even in the best case, for ever living a functional life again.

I just know that I’m here, I feel fine, and I owe that to Hashem’s great personal miracle and to so many special people. And I’m forever humbled by gratitude and a sense of mission. I’ve been through a lot, and I’m working on becoming a better person for it.

I

’d known since I was a kid that I would serve in the US Armed Forces, as did my grandfather and brothers. We were raised with profound gratitude to the United States for liberating my family during the Holocaust, and always nurtured an obligation to give back, even years later.

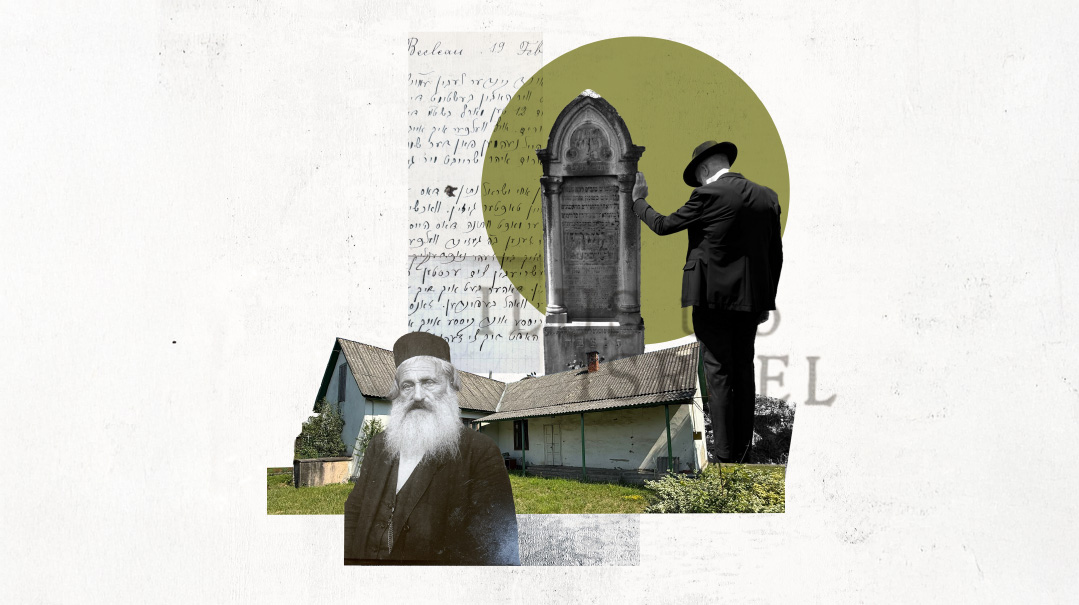

My father’s roots trace to Ukraine, as reflected in our family name: Abramoff. My paternal grandfather’s family fled their hometown of Berditchiv in the early 1900s, forced out by persistent anti-Jewish pogroms and Bolshevik violence. They settled in the Netherlands before World War II — my grandmother’s family was originally Dutch — and that’s where they were when Hitler’s marauders swept across Europe.

My grandfather and his siblings survived the war as children hiding in Dordrecht, Netherlands, while the vast majority of the local Jewish community was murdered. Toward the end of the war, Opa’s village was liberated by North American troops. As he watched the soldiers roll into town, bringing the promise of freedom and safety, he vowed to join them. Although they were Canadian, he was under the impression that the liberators were from the US. When he turned 18, he traveled to the United States, enlisted in the US Army, and served in the 101st Airborne Division during the Korean War. After completing his enlistment, he returned to the Netherlands. But burned by the war, Opa wanted nothing to do with Judaism or Jews afterward. He changed his name to Braamhof, a common Dutch last name, and married a non-Jewish woman.

My father was not born Jewish, but he sought out the religion and nation of his ancestors and became a ger at age 18. He married my mother, who was born Jewish of Dutch descent, and while still living in the Netherlands, changed his name back to reflect his Jewish lineage.

My parents lived in the Netherlands until 2003, when my father, an ophthalmologist, accepted a position at the University of Iowa. My mother, who is a child psychiatrist, was pregnant with me when we made the transatlantic voyage aboard the Queen Elizabeth II, fulfilling a lifelong dream to move to America.

My parents gave us very Jewish names and raised us with a strong Jewish identity, despite the fact that, in Iowa City, Iowa, there wasn’t a lot of Jewish infrastructure. Our family identified as Conservative, attending the local temple as well as Chabad of Iowa City. We kept some manner of kosher, learned Hebrew, and went to Sunday school. My two brothers and I had a bar mitzvah, and as we came of age, joined the Armed Forces. Yair enrolled in the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, serving as an officer aboard a submarine following graduation. Nathan went to the US Air Force Academy (USAFA) in Colorado Springs, and is currently a Space Force officer. As the youngest, I figured I would go to West Point, completing the family trifecta of all three US military service academies.

I applied and received Congressional appointments to all three academies. After touring the schools, I opted to go to the Air Force Academy, beginning in June of 2022. I wanted to be a pilot, and I found the Air Force’s academics more in line with what I was looking for than West Point. The kicker was when Frank Kendall, the Secretary of the Air Force at the time (and a West Point grad himself) called me to pitch it.

B

asic cadet training went by quickly, and I was soon deep into the academic year at USAFA. The schedule is hectic and demanding, and I always made sure to join the Jewish services and events, and was an active member of the community of about 35 Jewish cadets. I’d also established a connection with Chaplain Saul Rappeport, the Jewish chaplain stationed at USAFA at the time.

I loved the experience at the academy. At the end of the academic year, I enrolled in one of several special training programs that took place over the summer. Airmanship 490 is free-fall solo parachute training, where cadets train to become expert jumpers. After five solo jumps, we earn our jump wings. By late July of 2023, I had two successful jumps under my belt, and a third scheduled for July 31.

And that’s where my memory ends.

I have no recollection of anything that happened on that day, the preceding day, or the few months that followed. My memory restarts sometime in late September or early October — I definitely remember October 7, 2023, the day of the Hamas invasion in Israel (and my 21st birthday, which we marked in the hospital). The first recollection I have is of my mother putting my socks on, and me screaming at her to stop because it was too painful to bear.

Based on reports from doctors, friends, family, and official investigations, this is a summary of what happened on that day. While most of the details have been classified, what I can share is the following.

The jump on July 31st started like any other. We took off from the Academy’s Davis Airfield into a clear blue Colorado sky. Most of the jumpers completed their freefall and parachute landing, successfully touching down in the Olmstead Drop Zone, where I aimed to land as well.

But when I dropped out of the Twin Otter aircraft and pulled the cord to open my parachute, something went wrong. The parachute did not fully deploy, only partially slowing my fall and sending me into a spin. Ordinarily, I would have pulled the reserve chute, but photos and videos of the fall, which are all classified (even records of my first two successful jumps were classified), show that I was already unconscious. It isn’t clear why: One theory was that I had a minor stroke, lost consciousness because of the altitude and oxygen deprivation, or possibly I was struck on the head at some point. Whatever it was, I was incapacitated while falling, and unable to trigger the emergency parachute.

The Cessna pilots watched helplessly from above as I spiraled toward the ground, speeding to an impact site along the railroad tracks that skirt the airfield. They radioed command post to send an ambulance, although they knew it would be pointless.

I struck the gravel ground near the tracks, just where they run under an overpass. According to some instruments I was wearing, my body hit the earth at over 70 miles per hour. In videos of the accident, it’s clear that I bounced several feet in the air after impact and then lay still, face down.

Mrs. Alicia Shamblin was driving across the overpass on her way home from shopping at Costco when she saw all the parachutes coming down. She could see that something was wrong with mine, and that I was going to miss the drop zone and crash. A trained nurse, she pulled off the road just beyond the overpass and ran down the embankment, running through thorn bushes and cacti in her flip-flops as she raced to get to the spot where she saw I was heading.

She later told reporters that she didn’t think for a moment that I would survive the fall, but she couldn’t bear to let me die alone. She was there when I hit the ground — and to her utter shock, I still had a pulse. She cleared the gravel and dirt out of my airway, using her medical skills to stabilize me and immobilize my spine and back. Doctors later told me that there is no reason, no explanation, for how I survived the fall. But it’s clear that had Mrs. Shamblin not been there, ready and trained, when I hit, I would certainly have died within moments.

Mrs. Shamblin is a very religious woman, and later she told people that it was surely Divine intervention. “I don’t believe it was a coincidence,” she would say. “I call it a ‘G-d incidence.’ ” She was very protective of me afterward, telling everyone that I’m her fourth child, and that she can’t wait for a wedding invitation and a baby announcement.

An ambulance arrived at the scene and transported me to the emergency room at Penrose Hospital in Colorado Springs, where I was rushed into the first of several surgeries to address severe internal bleeding and the risk of organ failure. My parents were called, told that I had been in a serious accident, and that it was unclear if I would live much longer.

The hospital identified severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), along with a broken pelvis, several fractured vertebrae, spinal injuries, and pervasive internal bleeding. In surgery, my pelvis was screwed back together (I’ll always have six inches of titanium as a souvenir), my spine was set and damaged nerves treated, I was put on a feeding tube, and was kept in a medically-induced coma until I was treated for the primary trauma and stabilized.

In another clear miracle, the doctors were unhappy with my breathing, and planned to surgically install a tracheal implant to help me breathe. That would have been difficult to reverse. I was already in the OR when a nurse did a final check just before the surgery, and found that my breathing had suddenly improved. The surgery was called off. Doctors later told me they didn’t think I would ever be able to breathe on my own again.

It was a miracle from Hashem alone that I was alive. I was in pretty bad shape, and it would take another miracle to recover, but miracles, it seemed, were becoming commonplace.

Iwas transferred to James Halley Veterans Hospital in Tampa Bay, Florida, for long-term recovery, because it’s considered the best hospital in the country for treating TBI.

MRI imaging of my brain showed massive hemorrhaging and brain damage. The destroyed parts of my brain have yet to recover, as recent imaging has shown, and the healthy parts would need to learn all the functions that had been handled by the damaged part. Doctors at the brain injury unit were unsure if I could recover at all. Most of their patients are stroke victims in their 60s or 70s; those brains are no longer in the development stage as is the brain of a 19-year-old. They were interested to see what would happen with me.

At first, I was like an infant: What was left of my brain was not developed enough to store memories, or to control even basic movement. I was incontinent and needed to be washed and fed, just like a newborn.

And then, something started to shift. In mid-September, I began to store memories again, albeit fuzzily. I couldn’t understand what was happening, who I was, who the people around me were, or what had happened to me. All I knew was that I was in intense physical pain, surrounded by so, so many tubes sticking in and out of my body. I couldn’t move and I couldn’t process visuals — it took a long time until I recognized my mom’s face, and then my dad and brothers. My family tried to explain things to me in the simplest terms, but my injured brain couldn’t grasp much.

Most critically, I didn’t understand that the situation could well be temporary, and that there was a chance, albeit slim, that I would recover. It felt like this was my forever, and I began to battle deep depression. If spiritual health is a key component of positive physical health outcomes, I had none.

My turning point came one night when I had a talk with G-d, although I’m still ashamed to admit what I told Him. By now I understood that there had been an accident, and that Hashem had saved my life by a miracle.

I asked Him, “Why?!”

I begged G-d to just take me away and end this suffering. I was locked in a life that was not living. “If this is what I’m meant to be like, why did You save me?” I cried. “What’s the point in living like this, immobile and in constant pain? Why didn’t You just finish me off?” I cried myself to sleep.

When I awoke, it was suddenly clear to me that if Hashem had spared me, He must have had a good reason for keeping me around. And that meant that maybe I could actually get better if I worked hard at it. The Jewish chaplain assigned to nearby MacDill Air Force Base, Rabbi Elie Estrin, who is also the executive assistant to the endorser and military personnel liaison at the Aleph Institute, came to visit me, lifting my spirits and restoring my faith. My Chabad rabbi from back home in Iowa City, Rabbi Avremel Blesofsky, visited multiple times and helped me work through what was happening. They were able to shift my thinking from, “Hashem, why would you do this to me?” to “Hashem, thank You so much for all the miracles You have done and continue to do for me!”

And so, I committed to spare no effort to recover. There was a long road still ahead. I faced endless months of therapies, medications, and tests. I needed to learn to sit up, use a wheelchair, and eat solid food — walking, running, or going about normal life was a far-off dream.

I also committed to strengthen my connection to Hashem. I vowed to put on tefillin every day. Rabbi Estrin brought me a pair, and I have worn them every weekday since. I’ve also increased kosher observance and several other mitzvos. Rabbi Estrin brought supplies for Rosh Hashanah and Succos, blew shofar for me, and held a Kol Nidrei service in the hospital. The love and care shown by these rabbanim and the Jewish community gave me the spiritual strength I so sorely needed.

I threw myself into therapy for eight hours every day. There was physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, neurological training, and more. I learned to eat like a baby learns — first it was blended mash, then I slowly learned to chew, progressively handling more solid foods. I had to be monitored carefully when eating, because there was always a danger of choking. I chewed 12 pills each day, because I couldn’t swallow.

I slowly learned to control my limbs again, use a wheelchair, and eventually move about. When I could finally get out of bed, I was confined to a wheelchair for ten weeks as I learned to walk.

I’m really lucky and blessed in so many ways. It struck me recently what a blessing it was that this happened when I was 19 years old, and my brain was still in its neuroplasticity stage of development. This allowed it to learn these functions relatively quickly. The neurologists told me that had I been just a few years older, say 25 or so, it would have been so much harder to recover, and I probably would not have been able to regain all the essential skills.

With time, I grew stronger, and was finally discharged from the hospital on November 17, 2023, after 110 days. It was the happiest day of my life! I was so grateful to be able to wake up, to breathe, to walk and climb stairs. About two weeks after I was released, the Jewish Choir, which I helped restart at the Air Force Academy after it had been dormant for about 30 years, was invited to the White House Chanukah Party, and I was privileged to be able to join them. It was surreal — less than a month earlier I was stuck in a wheelchair, and now here I was, in service dress uniform, singing in the Executive Mansion.

B

ut with all the progress, I was nowhere near even thinking about returning to the Academy. I went home, back to Iowa City, and continued physical therapy and reconditioning. I set myself goals: to jog, eventually to run, and finally to do strength training. When I was at long last able to complete one pushup, I was so excited that I kissed the ground at the bottom of the rep.

The most amazing thing was that, pushing forward with grit and tenacity, at long last I was able to meet Air Force Academy standards, and could start working on re-enrolling. I visited during the year and spoke to the cadets, basically just to sort of show them that I was alive and standing. The decision to take me back was made by the Secretary of the Air Force on the recommendation of the superintendent of USAFA and the congresswoman who nominated me, Rep. Mariannette Miller-Meeks of Iowa. The plan was that I would enroll in the University of Iowa for the remainder of the year, and if I did well academically, I could come back to USAFA the following academic year.

I returned to the Academy in the fall of 2024, where I continued to excel, double-majoring in aeronautical engineering and applied mathematics in the honors program. I was also put in charge of the Recondo program, helping cadets who have slipped below physical fitness standards recondition themselves. I guess they figured my determination was a good example for them. I’m still hoping to get a pilot slot, but there are waivers required. The superintendent has to go before a board and explain why someone with my history of brain injury and spinal fractures should be given an exception to policy and sent to pilot training.

Today, I’ve returned to full physical fitness as I was previous to the accident. There are some minor hitches, though — the main nerve in my left leg had been severed, and is regenerating very slowly. This leaves me with less power, affecting my sprint speed and long jump (both part of the academy fitness test). I’m not quite the top athlete I was in high school — or even in my first year at USAFA, where I made the competitive lifting and freestyle ski teams and maxed out the majority of my fitness tests. But these are small things.

I also have to be extremely vigilant not to hit my head again. What would be a minor bump for others could be catastrophic for me. That means no more skiing, football, or any of the other high-impact sports I used to love. While swimming this year, I slipped, bumped my head, and wound up with a concussion. Overall, my brain is functioning well, but not quite as sharply as it used to. On cognitive tests, my processing speed is definitely slower than before, and I’m not easily getting straight A’s like I once did. But that just means I need to work harder.

I’m nothing if not blessed — it’s astounding how my brain has recovered. I consistently score in the 99.9th percentile on neuropsychological cognitive tests at Fort Carson, near USAFA. I had a brain MRI done recently, and the first thing the doctor said was, “Based on this MRI, you should not be in college.” But I am — and doing really well. I’ve done and presented great amounts of hypersonic research at the USAFA Aero Lab, the Arnold Engineering Development Center in Tennessee, and the Air Force Research Lab Space Vehicles Directorate in New Mexico, and have ongoing and future work with Oxford. The academy is an undergraduate degree, and I still have my eyes set on graduate school.

I’m excelling physically as well, and am now in as good as — if not better — shape than I was before the accident. I can still achieve full marks on most events in the Academy Fitness Test.

This spring, I trained in powered flight, because I haven’t yet been cleared to jump again. I know it sounds strange, maybe even a little off, but I hope I’ll get clearance soon — I really do want to finish the program and finally earn my jump wings. I wanted to join Wings of Blue, the Academy parachuting team, but I missed the window for that.

I

’ve always believed in G-d and considered myself religious and spiritually-sensitive, but now it’s clear to me that Hashem saved me and allowed me to recover for the sake of a Higher Purpose.

I have also had to become deeply disciplined and hard-working. Previously — and without meaning to sound haughty or egotistical — everything came easy for me. I got straight A’s and did really well on standardized tests almost without trying; I was captain of my high school football team and track team without devoting too much energy or focus to it. Life was exactly what I made of it and I could be successful at pretty much whatever I wanted. And then suddenly, I had to struggle just to walk or get my brain to cooperate. Even today, I’m on a strict nutrition plan, and my sleep, exercise, food intake, and time management are very carefully regimented and optimized by a team of specialists who hope for my continued recovery. Nothing is easy anymore. I have to be disciplined and deliberate about every little part of my life.

So when I wake up and have a hard day ahead, I put on my tefillin, and it grounds me. I remember to be grateful. I remember the mornings when I woke up and couldn’t move at all. I thank G-d just to be alive and healthy, I thank Him for being born, for my great family and supportive environment, for all the blessings and opportunity I have been given. I try to focus on what matters most in life, and try to maximize the gift of every waking moment. By staying grateful for every second of every hour of every day, and keeping in mind the countless people who invested so much time, effort and expense into me, it’s the easiest thing in the world to put my head down and focus on being better.

Hanging On

By Chaplain Saul Rappeport

When I got the call on July 31 about an accident at jump class in the airfield, I knew this was going to be a death notification and fatality support. Having completed the jump class myself earlier that year, I understood that there were no injuries in parachute training, only deaths. Thankfully, USAFA had a clean safety record with no recorded accidents — that was good, because there was no wiggle room or middle ground.

I visited the commander of the squadron who had experienced the accident, not knowing who the cadet involved was. When I heard that he was from Iowa, I started to get nervous; when the name was confirmed, my world started spinning. Boaz!

I rushed to the hospital to be with him, and was allowed into his room. He was in a coma and looked terrible — battered and shattered almost beyond recognition. I met his parents in the lobby — they had dropped everything and driven straight from Iowa, also expecting to have to arrange a funeral on arrival. But to everyone’s surprise, Boaz was hanging on.

For the next several weeks, the Jewish cadet community and the Abramoffs rallied around Boaz in the hospital room. We said Tehillim, davened Friday night there, with Kiddush and hamotzi in his room. After a week and a half, Boaz came out of the coma, but was clearly disoriented and faded in and out of consciousness. The doctors assumed there would be severe, permanent brain damage, and the extent to which he would regain function was unknown.

But Boaz surprised us all. In his vaguely conscious state, one Friday night, we asked him if he recognized the people in the room, and he was able to say, “That’s Sam, that’s Levi, this is Rabbi.”

Boaz’s family and the other cadets did everything they could to help. Someone had said that it was beneficial to have brain stimulation going on in the background, even when he was unconscious, so they took turns talking to him or reading aloud. Once, his father told him a devar Torah and added, “Isn’t this your bar mitzvah parshah?” Boaz said, “No, my bar mitzvah parshah is Ha’azinu,” and proceeded to rattle off the first ten pesukim, by heart, with the trop.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1082)

Oops! We could not locate your form.