Backfired

| September 30, 2025Do our teens pay the price when we’re there for our babies?

I

was the proud mother of one delicious baby boy when I remember being jolted by the news. Three different women whom I considered major mentor material — successful, full-time mechanchos in major seminaries — had quit working or significantly reduced their hours so they could spend more time with their children.

Huh? None of them had babies or toddlers. They all had teenagers — children old enough to manage a few hours a day without Mommy, and to help with the younger ones. It seemed absurd to me that they were quitting work just when they seemed to finally have the most time for it.

Years later, I understood. So did the group of friends I was sitting with at a wedding. Leora and Dina were in their thirties, just starting to raise teenagers, while Chaya and I were well into our teen parenting journey. But we all shared one thing in common, and I summed it up with a line stolen from Rav Uri Zohar a”h.

“My friends,” I said, “we were robbed.”

Keep Them Close

When we’d been young adults, we’d heard — and fervently bought into — the hype about staying home with little babies and toddlers. We knew the science: attachment theory, the brain development that occurs before the age of three. We were ready to jump through any hoops it would take to keep our babies and toddlers home with us.

Most of us didn’t have the luxury of not working at all, but we managed to work part-time, from home, or at night, so that we wouldn’t have to leave our babies with babysitters. No one can care for your baby the way you can, we knew. We looked down on friends who did not share our philosophy.

“My oldest was a kvetchy baby who couldn’t fall asleep without nursing,” Leora related. “I didn’t think any babysitter would have the patience to soothe her to sleep over and over again at forty-five-minute intervals, so I decided not to go back to school as I’d planned. I wanted to be the Mommy I was supposed to be to her and the babies that came after her.”

The rest of us nodded in commiseration. Instead of considering what they really wanted to do, Dina and Chaya had accepted minimum-wage jobs that worked with their short-term parenting plans. Dina did mind-numbing data entry from home, and Chaya worked as a night secretary for a small sheitel salon.

But if being a mommy meant lower-paying jobs with less possibility of advancement, it was worth it. If we felt a bit understimulated, or that our talents were untapped, we had a whole life waiting for us as soon as our youngest started school. For now, our children were our priority.

As our children got older, though, the reality of life was that we couldn’t afford not to work. The scrimping and saving you can get away with when all your kids are little just doesn’t work when they’re older. You can no longer serve oatmeal for supper, and even if you’re not buying the trendiest, most up-to-date styles, your kids still have to fit in with their peers. Your children need evaluations and entertainment and transportation. The older they get, the more their needs cost.

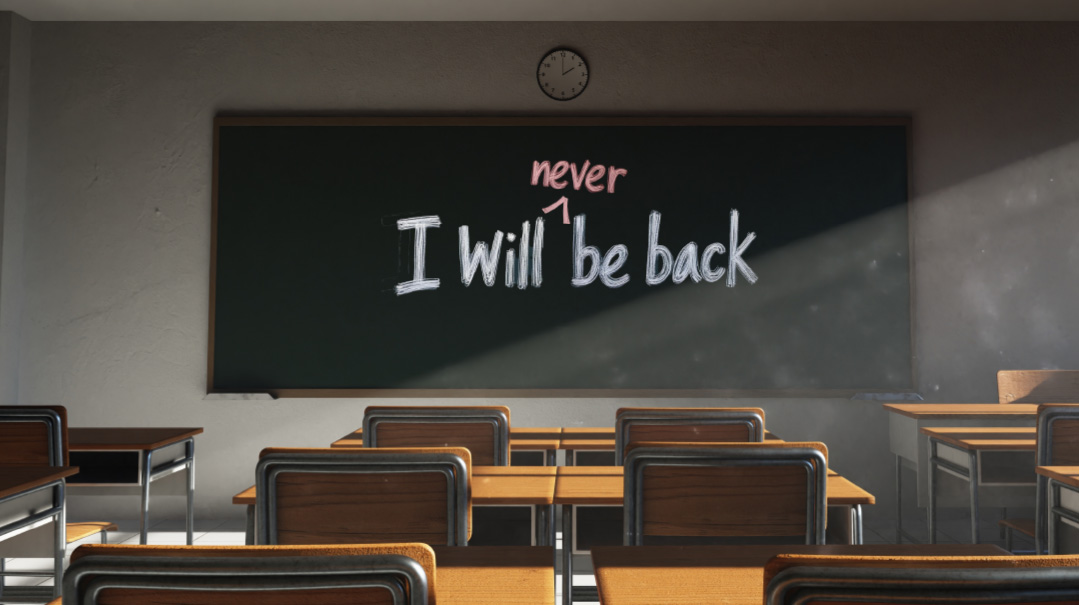

So as our children (and family size) grew, we’d been forced to change our lifestyles. Some of us found ourselves working on advanced degrees while trying to run big, busy households. Others took whatever jobs they could get — but entry-level positions and salaries leave little room for flexibility. The baby Leora wouldn’t leave with a babysitter was now a 14-year-old letting herself into an empty house and preparing snacks for the younger kids while Leora got the master’s she’d denied herself years before.

“Hopefully this will pay off in the future, and when my youngest is in high school, I can be there for him when he gets home.” Leora sighed. “But that’s a long way down the line. After I get my degree, I still need years of experience to give me the professional flexibility I’ll need to have more control over my time.”

Backfired

We all had different stories, but the same takeaway. We each felt that by committing to being full-time carers for our babies, we’d ended up depriving them of more important things when they were older. Yes, a lot of very crucial development happens before the age of three. But it’s not like children are ready to be independent at four; the brain is still developing until age 25. And the older they get, the less a child’s need for their parent can be filled by someone else

A baby can flourish at a loving babysitter, and your toddler will enjoy the park with any safe adult. It’s your older children and teens who need to be listened to. They need an attentive adult around, someone who’ll pick up on what they’re not saying. They need to feel cared about, just as much as a younger child.

At our table, Leora laughed. “I was so worried about leaving my baby who didn’t know how to fall asleep on her own with a babysitter. But most likely a loving and experienced babysitter would’ve helped my baby learn to fall asleep on her own within days. She would’ve been a happier and better-rested baby.”

But there’s no one else who can notice the glow on your fourth grader’s face when they greet you at the end of the day and wait for you to guess they’ve won the weekly raffle. You’ll be hard-pressed to find someone else to shop with your preteen daughter and give over the value of feeling good about herself while being tzanuah.

Whether they’d been in school, working for others, or building private practices, those peers we’d looked down on all those years ago for leaving their babies were now able to be more selective in their work today, allowing them to better meet the needs of their families. Some of them were outsourcing work, others had the reputation and experience to raise their fees and cut back on their hours, or enough job offers that they could agree to take only projects that didn’t overlap with family time.

Gila, another friend who’s about my age, walked over to our table. “Looks like an interesting conversation. Mind if I join?”

“You don’t belong here.” Chaya teased. “We’re all bemoaning the fact we didn’t do what you did and work before our babies grew up.” Gila had gotten her MSW and seen clients all these years. She’s become so well known that people are willing to pay top dollar for her. I know she’s really careful not to work hours that interfere with her family time.

The condescension we’d felt years ago toward the working mothers like Gila was now replaced with envy. In the big picture, it was clear that the women who had been working or in school when their kids were babies had an advantage with their families that we didn’t. The exact thing we’d done to be there for our families had backfired on us.

“Don’t make this about solving your financial situation,” Gila said. “I’m managing better now than I would have without my job experience, but we’re still not making ends meet. The bottom line is now that my kids are older, I need to be around for them — whether or not we can afford it.”

Incorrect Instincts

I watched everyone nodding, agreeing with Gila, and I thought, This isn’t just about working or staying home with your baby.

Babies are so small and so helpless and so cute. They naturally tug at our emotions, and we feel a need to protect them. But we can’t let that distract us. Bigger (and sometimes less cute) kids still need their parents. Maybe even more than babies do.

I shared a story from a recent Shabbos afternoon in my own home. “The adults and older children were sitting at my Shabbos table when my two-and-half-year-old granddaughter, Rachel, started wailing from the corner where she and my ten-year-old, Eliyahu, were playing.

Through her sobs, we heard her accusing Eliyahu of doing something to her.

Everyone jumped on Eliyahu.

“What did you do?”

“Did you hit her?”

“Do you really have to fight with a two-year-old?”

Flustered at our attack, Eliyahu tried to explain.

“I didn’t hit her. She had my toy and—”

Which only invited more criticism. “He’s such a baby.”

“You have a zillion toys. You can’t find something else to play with?”

Tears threatening, Eliyahu ran to his room and closed the door.

It was his 17-year-old sister who came to his rescue.

“He’s not a baby. He’s right. Why does he have to give up everything to her, just because she’s younger? That’s not fair.”

I went to Eliyahu and got the whole story, I told my friends. It turned out that he hadn’t even taken a toy from Rachel. He wanted his toy; he’d let her play with it earlier, and when he wanted it back, he asked her where she’d left it. When she wasn’t able to articulate herself, he took her by the hand and asked her to show him where it was. Not wanting to interrupt her play, she’d cried when he tried to take her hand.

I couldn’t help but notice how instinctively we side with the younger child — no matter how old the kids are. If Eliyahu had been in a conflict with an older sibling, everyone would’ve assumed he was in the right before hearing the whole story, I finished.

“It’s so true,” Gila said.

As if on cue, Dina, Chaya and Leora in turn each mocked typical parent lines.

“Give her the last cookie. You’re bigger.”

“Let him go first. He’s little and not as patient as you are.”

“The baby needs Mommy right now. I’ll help you soon.”

We all laughed, but I believe it’s an instinct we need to override.

The older a child gets, the less they depend on us physically. But children of all ages need the emotional security of knowing that they’re important to their parents. They need to know they can rely on their parents at all times — not only when no one younger also needs them. Everyone needs to know they matter.

Everyone needs the security of knowing there are things that belong to them, and no one can take them away. But when the smaller child pulls at our heartstrings, our emotions often override our logic. Why on earth should the older child always have to lose their turn, their toy, their anything — just because there’s a younger child who wants something that doesn’t even belong to them? When two children need us at the same time, who says the younger one needs us more than the older one?

When I heard the rebbetzin in a parenting class say that we need to prioritize an older child’s emotional needs over a younger child’s physical needs, it resonated deeply. It’s a message that reverberates with anyone who grew up constantly stepping aside or waiting for parental attention that had been diverted to their younger sibling.

The table conversation was heating up. I leaned in to listen to Dina share, “I was pushing my double stroller through the park, when the front wheel got stuck on a rock and overturned. Baruch Hashem, neither child was seriously hurt, but they were both startled and crying. I remember how bystanders were shocked that I picked up and comforted my three-year-old before my one-year-old. But my three-year-old is old enough to understand how scary it was and remember what happened. She needed me more than the baby who would calm down as soon as she was picked up and forget it ever happened.”

Often the “older” children aren’t very old. It could be a six-year-old, or even a four-year-old we’re asking to step aside. Something about seeing a younger child cry triggers something in our neural pathways. But we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking it’s about teaching the value of vitur to the older child; this is about soothing our misguided emotions. When an eight-year-old asks us for a sandwich at the same time as a teen, we view that eight-year-old as helpless and needy. But if that same eight-year-old is asking for his sandwich at the same time as a three-year-old, he’s suddenly old enough to wait? Where’s the logic in that?

Chaya offered the perfect example: “When I was six, I remember being asked to clean up after my little brother, ‘because he’s too little to clean up after himself.’ That made sense to me at the time. But when I was twelve and hearing the same line, it suddenly struck me: Hey, he’s the same age I was when I started cleaning up after him. Why can’t he be expected to clean up after himself?

“At first my parents were resistant. My little brother seemed so, well, little. And I was so big and capable. I was bothered by the injustice, though, and I persisted. In the end my parents agreed with me.”

I’m not saying you should let a newborn cry in hunger, but there’s no reason a cranky two-year-old can’t cry while you cut an apple for your four-year-old. Let them both see that the four-year-old also matters. If your teenage daughter is nervous because she’s supposed to leave the house and can’t find the skirt she needs, who says her needs aren’t more pressing than the preschooler who’s crying for a snack?

It’s natural when two kids are fighting to blame the older one. It’s instinctual when two kids need us to respond to the one in the crib. But we need to become aware of it so we can engage our mind and determine who really needs us more at the moment. Maybe the older child isn’t as loud. We’ve taught our children to ask nicely, and maybe they’ve learned that. (And if they haven’t, is it possible we’ve taught them that you have to act like a baby to get something?) So we need to listen, really listen, because at every age our children need attentive parents. The older they get, and the more sophisticated their communication — the more we have to listen carefully to hear what they’re saying.

As parents, we watch our children grow, watching with pride as they go from tiny, squalling babies to independent adults. But it’s specifically as our children grow more independent that they need to see they still matter to us. There is no age limit to needing love, attention, and acceptance.

Chaya stood up.

“Where are you going?” Gila asked. “They haven’t served dessert yet.”

“I have a yeshivah bochur coming home after a long day. I’d like to get home in time to spend some time with him.”

Well, we couldn’t argue with that, could we?

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 963)

Oops! We could not locate your form.