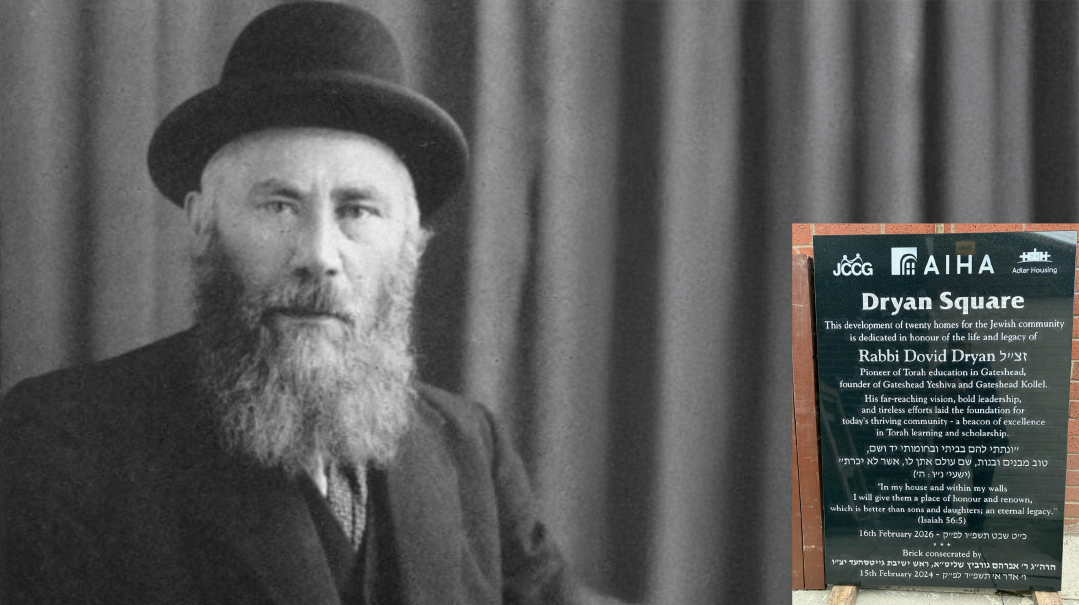

Opening Up the Gates of Zion

| September 2, 2025From the moment he assumed office in 1921, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook leveraged every tool at his disposal to champion aliyah

Title: Opening Up the Gates of Zion

Location: British Mandate Palestine

Document: Chief Rabbinate immigration dossier

Time: 1920s and ’30s

British authorities looked on sternly as the elderly rabbi pleaded on behalf of a boatload of “illegal” Jews who had slipped into Haifa harbor under cover of darkness. It was the early 1930s, and British Mandate officials were preparing to deport new arrivals to Palestine who exceeded the immigration quota. Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook — the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of the Yishuv — requested an urgent audience with the High Commissioner.

The commissioner was perplexed. How could the chief rabbi ask him to bend British immigration law, when the tradition of dina d’malchusa dina teaches Jews to respect the law of the land? Rav Kook answered with a bold twist: “The law refers to new immigrants. But these people are not new immigrants — they are returning citizens.” Citing Tehillim and Chazal, he explained that anyone who “yearns for Tzion” is considered as if he was born there. These Jews, he insisted, weren’t foreign interlopers at all. They were children coming home.

The commissioner, flabbergasted, had no response. In the end, the deportations were halted, a testament to Rav Kook’s mix of passionate advocacy and deft diplomacy. It was just one example of the tireless efforts he would spearhead to keep the gates of the Holy Land open for the Jewish People.

M

any years before he ascended to the post of chief rabbi, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook’s life already embodied the pull of immigration to Eretz Yisrael. In 1904 he left a prestigious rabbinic post in Europe to settle in Jaffa, assuming spiritual leadership of the new moshavim and pioneering kibbutzim. Rav Kook saw building Eretz Yisrael as a holy mission. He urged his fellow Jews back in Europe to join him in settling the Land so that together they could fulfill the “forgotten mitzvos” that could only be observed in the Jewish People’s ancestral homeland.

During World War I, stranded in London, he lobbied for the Balfour Declaration of 1917 and publicly thanked British leaders (with his newfound English-speaking ability) for promising a homeland to the Jewish People. By the time he returned in 1919, the stage had been set: The British Mandate over Palestine began, and Rav Kook was unanimously chosen to serve as chief rabbi of Jerusalem, and soon of all Palestine. In this new role, approved by the British government, his lifelong dream of facilitating Jewish return to Zion became an urgent practical mission.

But passage through the gates of Zion was not left in Jewish hands. The British, bowing to political pressure, imposed growing limits on immigration. Starting with the 1922 White Paper, London declared that Jewish entry must not exceed the “economic absorptive capacity” of the country, which in actuality was just a pretext to placate Arab opposition. This was necessary because the Suez Canal had become a lifeline for the Royal Navy and Britain’s merchant marine fleet to India, and because of newly discovered petroleum in Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf. British imperial policy took a decided shift away from previous obligations to facilitate the establishment of a Jewish national homeland in Palestine.

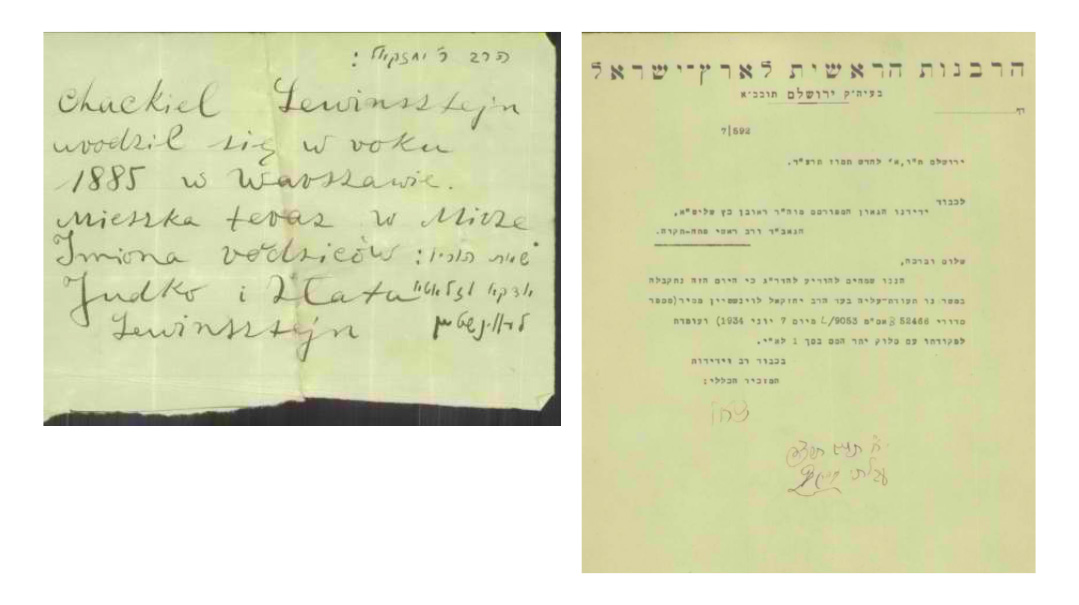

Quotas and certificates became the bureaucratic buzzwords of the era. Every potential Jewish immigrant now required a stamped British “Certificate of Immigration” in hand before setting sail. Applicants had to navigate a maze of forms and proofs. They were asked about family dependents, required to show financial “means” or a promise of employment in Palestine, and even had to post a ₤100 bond to ensure they wouldn’t become a public burden.

With each passing year, the conditions tightened and the quotas shrank; by the mid-1930s, as Jewish desperation in Europe grew, the British gates on Palestine clanged nearly shut. Against this backdrop, Rav Kook used his office to help countless Jews seeking refuge in Eretz Yisrael.

From the moment he assumed office in 1921, Rav Kook leveraged every tool at his disposal to champion aliyah. He understood that for many rabbis and yeshivah students — who often lacked wealth or British connections — the Chief Rabbinate was the address to open doors. Rabbis, roshei yeshivah, and yeshivah students turned to Rav Kook for assistance in obtaining the documentation necessary for their approval from the British mandatory authorities.

Rav Kook did everything he could to assist those who he felt would be at the forefront of building a Torah and religious community in the rapidly developing Yishuv. Before long, letters from every corner of the Diaspora piled up on his desk — pleas from rabbanim in Poland, the Soviet Union, and Lithuania pleading for the chief rabbi’s endorsement to obtain the coveted certificates. Rav Kook personally penned recommendations and intervened with the British authorities.

Mandate authorities, prodded by his persistent lobbying, agreed to allocate a special pool of immigration permits for religious functionaries. Thanks to Rav Kook’s efforts, permits were set aside specifically for rabbis, who could bring their families along. In practice, this meant that if a rav or dayan could document his credentials, he now had a fighting chance to obtain that precious certificate. The Chief Rabbinate in Jerusalem dutifully issued letters certifying a petitioner’s rabbinic bona fides to satisfy British authorities.

F

or aspiring bnei Torah, Rav Kook likewise opened a door; his office secured student visas for dozens of yeshivah bochurim, officially as “students” of the new Merkaz Harav yeshivah he had founded. Many of these young bochurim were refugees from Soviet Russia or Poland — “children of Zion” escaping lands of oppression, now able to enter the Holy Land with Rav Kook’s stamp of approval.

Even the secular-run Jewish Agency came to rely on Rav Kook’s involvement. The Agency’s Immigration Department (headed by Yeshayahu “Heschel” Farbstein, a Mizrachi leader) maintained its own list of certificate allocations. Rav Kook would frequently send polite but firm directives to the Agency to ensure the rabbinic and yeshivah community got its share.

Among the many treasures in Israel’s National Archives are hulking binders meticulously assembled by Rav Kook’s office — each file a window into the gates he opened. There are letters requesting certificates for roshei yeshivah, pages of correspondence with the Jewish Agency, and signatures that unlocked new beginnings. Some names were old friends of Rav Kook from his days in Volozhin — Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, Rav Zelig Reuven Bengis, and others who shared the benches with him in the Netziv’s beis medrash. Others included chassidic rebbes, dayanim, and rabbanim from across Eastern Europe. Each case was treated as if it were the only one.

The files tell stories. There’s a letter from Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski introducing Rav Avraham Yeshaya Karelitz — the Chazon Ish — and warning Rav Kook that the reclusive scholar would not accept a public rabbinic post, so any assistance would need to come through surreptitious means. Shortly after the Chazon Ish’s arrival, Rav Chaim Ozer wanted to acquaint the two and requested that Rav Kook use his connections and ingenuity to assist with his financial support.

“I wanted to acquaint your brilliant eminence with this great man and ask you to persuade the powers that be to support him in accordance with the dignity he deserves,” wrote Rav Chaim Ozer. “That is, to buy his precious books, the three volumes of Chazon Ish. I hope that you will give this matter your attention…”

As it turned out, even at this early stage, Rav Kook was already familiar with the brilliant new arrival. Two days after docking at the Jaffa port, the Chazon Ish himself penned a letter with a halachic query to Rav Kook in his capacity as chief rabbi. He had heard that Rav Kook mandated a stringency regarding pidyon maaser sheini, in an area where the Chazon Ish wished to be lenient.

The Chazon Ish wrote to Rav Kook asking him to clarify this chumra. Opening the letter with the words, “His honored eminence, Maran Shlita,” he noted that he had just arrived in Eretz Yisrael when this question arose. Rav Kook duly answered, but the Chazon Ish responded that he planned on being meikil regardless, as he was in a situation of sha’as hadchak.

In subsequent correspondence with Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, Rav Kook emphasized that he was doing everythingin his capability to look after the welfare of the Chazon Ish. They later had the opportunity to meet face to face. When the Novardok yeshivah hosted a groundbreaking ceremony for their new building, Rav Kook was invited as the guest of honor. The Chazon Ish attended as well, standing in respect throughout the shiur of Rav Kook. The two met and conversed at this ceremony, as their one and only meeting.

A

nother file records the immigration paperwork of Rav Yechezkel Abramsky, then rav of Slutsk, whose way out was blocked by Soviet authorities and who was ultimately sent to Siberia for the “crime” of trying to leave the socialist “paradise.”

Rav Abramsky initially reached out to Rav Kook in 1925 with a heartrending and impassioned plea: “I hereby turn to his honored and brilliant self with a request. Please show kindness to me, and more importantly, to my family, and use your great influence to help make it possible for us to immigrate to the Holy Land…” Rav Yechezkel goes on to elaborate the spiritual dangers of raising children in the anti-religious environment of the Soviet Union, and fears for his children’s future. He feels that obtaining an immigration certificate to Palestine is his only hope.

Three years later, in a more optimistic tone, Rav Abramsky once again corresponded with Rav Kook, as it seemed that salvation was on the horizon: “Yesterday I received a telegram from Petach Tikvah with good news. With the help of Hashem, Who is exalted over all rulers, I was chosen unanimously to fill the honorable position of rabbi of the city. I’m sure that your brilliant eminence was instrumental in this decision, undoubtedly, you were one of those who tipped the scales in my favor. I therefore want to express my heartfelt thanks and blessings to you…”

Unfortunately, it didn’t ultimately materialize, and Rav Abramsky was arrested by the Soviets and deported to Siberia.

And there’s the case of Rav Yechezkel Levenstein, who arrived in 1935 to serve as mashgiach at the Lomza yeshivah in Petach Tikva — with the assistance of Rav Kook — before returning to Europe to take up the post in the Mir Yeshivah following the passing of Rav Yerucham Levovitz.

These weren’t one-off favors. They were part of a systematic effort to populate the Land with Torah and the people who carried it. Rav Kook believed that a flourishing Yishuv needed more than builders and farmers — it needed talmidei chachamim, poskim, mashgichim, and roshei yeshivah. And so, behind the scenes, certificate by certificate, letter by letter, he worked to make that happen — quietly laying the groundwork for the spiritual infrastructure of a future Torah center in Eretz Yisrael.

A Blessing for a Bibliophile

When Rav Reuven Margolis, the great Torah genius and author of more than 50 seforim, came to settle in Eretz Yisrael in 1934, he went to pay his respects to Rav Kook. This great Galician scholar was renowned as a bibliophile and for his mastery of the entire gamut of Torah literature. As the author of dozens of seforim on every conceivable Torah topic, he was also well versed in Kabbalah. Refusing to serve in any rabbinic formal capacity despite his glowing rabbinical ordination from the great Galician posek Rav Meir Arik, Rav Reuven Margolis eventually headed the Rambam library in Tel Aviv until his passing in 1971.

During his initial visit to Rav Kook, his host sensed that he was in the presence of Torah greatness and duly asked his guest to identify himself.

“I am Reuven Margolis from Lavov,” he humbly stated.

Upon hearing his name Rav Kook excused himself for a moment and then returned wearing his spodik. He then loudly recited the brachah of shehecheyanu — as one does for a friend he has not seen in some time.

Silent Support

Rav Kook endeavored to provide monetary support to the poor Torah scholars of Yerushalayim before the Yom Tov season. He quietly slipped envelopes of cash to them before Yom Tov — sometimes delivered to men who thundered against him from the pulpit. The money always traveled through students, a double lesson: give discreetly, and remember that even opponents are talmidei chachamim. They simply do not understand me, he would say, but they are yirei Shamayim.

Rav Shmuel Shezuri shared the following story: “One Erev Pesach, Rav Kook handed me an envelope for a zealot who had slandered him most viciously. ‘Please forgive me, but I can’t deliver money to someone who disgraced you,’ I told him. Rav Kook accepted my refusal without protest. I later discovered that he discreetly sent another emissary to deliver the funds. For him, kavod haTorah always came before kavod harav.”

The 3rd of Elul marked the 90th yahrtzeit of Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1077)

Oops! We could not locate your form.