At the Crossroads of Generations

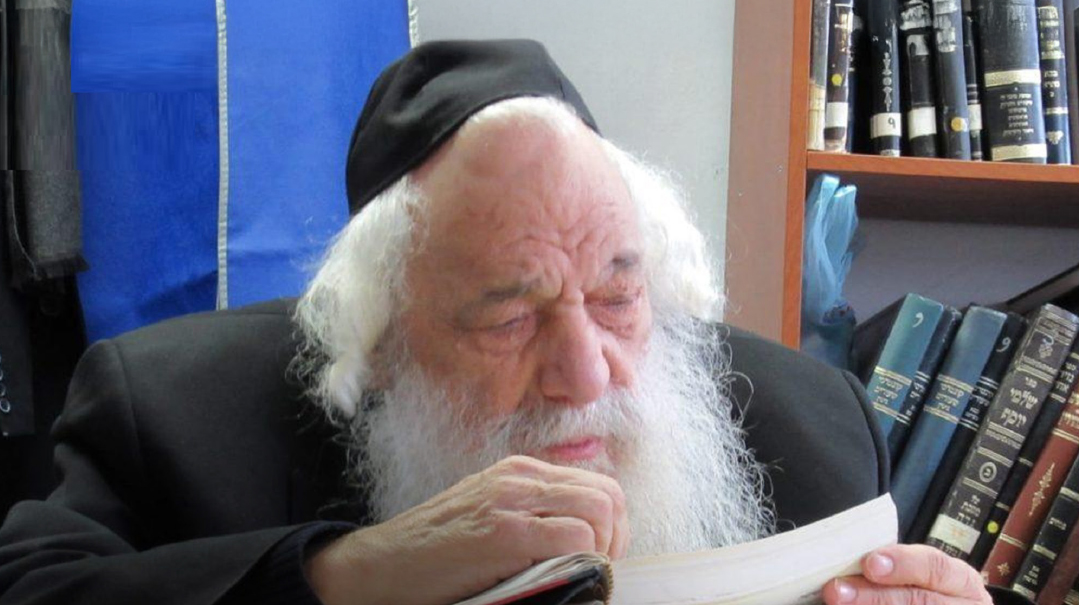

In memory of Rabbi Berel Wein

AS

was extensively covered in these pages last week (“Voice of History,” Issue 1075) and in tributes throughout the greater Jewish world, Rabbi Berel Wein was known for many things. His talmidim in yeshivah knew him simply as their rebbi and rosh yeshivah; his congregants knew him as their rav; many in the wider Jewish world knew him as a distinguished orator, head of kashrus at the OU, a venerated talmid chacham, and a prolific author of dozens of books on Jewish history and other educational topics. His trademark Chicago accent made his thousands of lectures on Jewish history, Navi, Pirkei Avos, and many other Torah subjects instantly recognizable. And of course, to his family he was a caring parent, doting grandfather, and proud great-grandfather.

But my connection to him was much more personal. For me, he served as a mentor, role model, guide, and teacher. I had grown up on his Jewish history books and cassette tapes — they kindled my passion for our nation’s past, which has continued unabated over the ensuing decades, even though it has transitioned from being my hobby to being my career. Interestingly enough, when I expressed concern to him that my passion for Jewish history would flag once it became my job, he set me straight with a healthy dose of pragmatic advice.

“Passion dissipates, a business is more likely to be long-lasting,” he told me.

As a child, I absorbed his recordings on prewar Lithuanian yeshivos, and later, I prepared lengthy notes from those lectures for the early tours I guided in Europe. It was then that I appreciated Rabbi Wein’s proximity to that vanished world. When he discussed Grodno and Rav Shimon Shkop, it was filtererd through the experiences of his father, Rav Zev Wein (known as “Reb Velvel Chullin” for his mastery of that particular masechta when he was a talmid of that yeshivah).

Likewise, Volozhin was the alma mater of his grandfather Rav Chaim Zvi Rubinstein, a close talmid of the Netziv, who later served as rosh yeshivah of Beis Medrash L’Torah in Chicago. Rabbi Wein related that he first studied the classic sefer Ketzos Hachoshen as a nine-year-old chavrusa of his grandfather. His father-in-law Rav Eliezer Levin was a talmid of Kelm and Radin and a ben bayis in the home of the Chofetz Chaim. His uncles and rebbeim in Chicago were all students of Slabodka, Telz, Baranovich, and Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin.

He created another impactful lecture series describing his relationships with great Jewish leaders of the 20th century: his rebbeim in Chicago, such as his rebbi muvhak Rav Chaim Kreiswirth and Rav Mendel Kaplan; in Miami, the Ponevezher Rav, the Satmar Rav, and others who came for fundraising or for the winter; during his tenure at the OU, towering personages like Rav Alexander Rosenberg; and during his years in Monsey, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky. And there were so many more.

Rabbi Wein used his position at a crossroads of Jewish history to its fullest potential. His own rich life experience gave him the perspective to utilize his prowess in every era of Jewish history — from the age of Chazal to Moorish Spain and Renaissance Italy, down to modern times — to imbue an entire generation with the values and traditions of our past.

W

hen I arrived at the Mir Yeshivah in 2003, Rabbi Wein’s grandson Binyamin Teitelbaum became my dirah-mate and eventually my dear friend. Through him, I was privileged to upgrade my relationship with Rabbi Wein. I went from absorbing his words through books and recorded audio to hearing him personally. I became a frequent guest at his Rechavia home for Shabbos seudos, accompanying him after davening at Beit Knesset Hanasi. I took the opportunity to pepper him with questions on every conceivable topic.

I once expressed consternation at hearing that Orthodox Jewish neighbors of a yeshivah had complained to authorities about the noise. Rabbi Wein wryly observed, “Az m’lernt nit ken mussar [if bochurim don’t study the character improvement teachings of mussar], what can be expected from his interpersonal behavior?”

I soon began attending his weekly Jewish history lectures at Ohr Somayach, which was conveniently located right near the Mir. After each lecture, I’d escort him to his next engagement, clarifying and asking questions on the new material he’d brought to light during that day’s talk. His brevity in answering queries was well-known, and the profound insights that he managed to condense into each terse reply was always astounding.

His healthy sense of balance of values and priorities defined his outlook on Jewish life and history. For example, he acknowledged that white shirts are important as a yeshivah mode of dress. But he tempered that with story of a talmid of his who had brought his son before his bar mitzvah.

“I asked him why he’s excited for his upcoming bar mitzvah.

“The boy replied, ‘Because then I get to wear tefillin and white shirts.’

“And therein lies the danger. If he equates the two in his mind, then if he drops white shirts one day, he may drop the tefillin as well.”

T

hroughout his life, even when he was known worldwide as a teacher of Jewish history, Rabbi Wein never viewed himself as a historian. In his mind, he was first and foremost a teacher of Torah. I once heard him express pride over a grandson who had just been appointed a rav: “He joined the family business. But we must realize that teaching Torah is all of our family’s business.”

He essentially pioneered the genre of Jewish history for the yeshivah community. All of us who enjoy history today, who study it casually or professionally, and who find relevance for the Jewish present and future in the stories of our past, are in essence following in his footsteps. He recognized early on that he was a role model, and he tried to instill the protocols of the historian’s craft in his emulators.

In introductions to some of his works, he would note his “bias” as a yeshivah-educated Orthodox Jewish historian. In Faith and Fate, a survey of 20th-century Jewish history — one of his most important works, which later had a spin-off as a popular documentary series — he included this “disclaimer”:

I have concentrated on describing in some detail Orthodox Jewish life in this [20th] century as part of the overall story. This is due to my personal bias that Orthodoxy remains the most vital and creative element in the Jewish world and also because of my belief in the divinity of the Torah, the authenticity of the Orthodox tradition and its unique role in ensuring the survival of the Jewish people throughout the ages. Nevertheless, I have attempted not to ignore other movements and groupings in the Jewish story of this last century and to accord them their fair due. This work is meant as a history book and not as a religious polemic.

His practicality manifested itself in many other ways as well. For example, I attended all of his book launch events, and made sure to have him sign each new edition for posterity. I once stayed till the end of a launch and witnessed the octogenarian Rabbi Wein schlepping around the chairs and speaker system in order to tidy up the event hall. I pointed this out to his grandson, Rabbi Yitzchak Gettinger (at that time my friend Yitzy).

He said, “You want to know the craziest thing about it? He doesn’t care. These things need to be put away, so he’s putting them away.”

W

hen I still lived in Jerusalem’s Ramat Eshkol neighborhood, I’d trek to Rechavia on Shabbos Shuvah and Shabbos Hagadol to hear his drashah. These were veritable works of art, in which he weaved together halachah, drush, Navi, stories, jokes, and history into one tapestry, mesmerizing the audience and readying us all for the upcoming holiday. He occasionally got quite emotional (or as emotional as a Litvak could get).

Once, he was expounding on a nevuah of Zechariah, which he generally referred to as “current events,” in order to impress upon his audience the immediate relevancy of the holy words. The Navi Zechariah declares (12:11): “Bayom hahu yigdal hamisped biYerushalayim [On that day there shall be great mourning in Yerushalayim].”

In context, this pasuk appears strange, Rabbi Wein said. This comes as part of a larger prophecy in which Zechariah describes the great Final Redemption, and the awesome happiness enjoyed by all the returnees to Yerushalayim. Why would there be a great mourning on that day? Rabbi Wein cited a commentary that provides an insight into our current situation.

In the midst of the exile, we are in survival mode — either desperately trying to survive during an existential crisis, or completely focused on the future, trying to rebuild after the most recent travail. We never have a moment to dwell on the past and properly mourn our own suffering during our long exile. Only when the Redemption arrives will we have the peace of mind to be able to cry, to finally mourn our many tribulations as a people and as individuals.

This insight was so profound for me at the time. Part of our yearning for Geulah was to afford ourselves the opportunity to mourn, to attain a sense of closure that was denied to us in the exile. With Rabbi Wein’s brilliant delivery, his clarity and masterful oratory skills, I can honestly say that I have never yearned more for the Geulah than at that moment. I so desperately wanted to be able to mourn properly for our suffering in this long galus.

Together with my rebbi Rav Yosef Elefant, I honored Rabbi Wein as a witness at my chuppah. As I was closing the door to the yichud room, the last thing I heard was the booming familiar voice of Rabbi Wein — “Well, Rabbi Elefant, it was very pleasant spending the evening with you.”

I can now say, “Well, Rabbi Wein, it was very pleasant spending all those years with you.” You were a teacher and guide, and a mentor to me in Jewish history. Anything I’ve tried to develop in my own journey through the field of Jewish history, whether in the For the Record column in these pages with my dear friend and collaborator Dovi Safier, in the Jewish History Soundbites podcast, or in my Jewish history tours across Europe and Israel, has all come from your teachings and inspiration.

Rabbi Berel Wein lived through history, appreciated the value of history, loved history, was a bridge for history, taught history and ultimately — and most importantly — made history.

Yehi zichro baruch.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1076)

Oops! We could not locate your form.