Unlimited Horizons

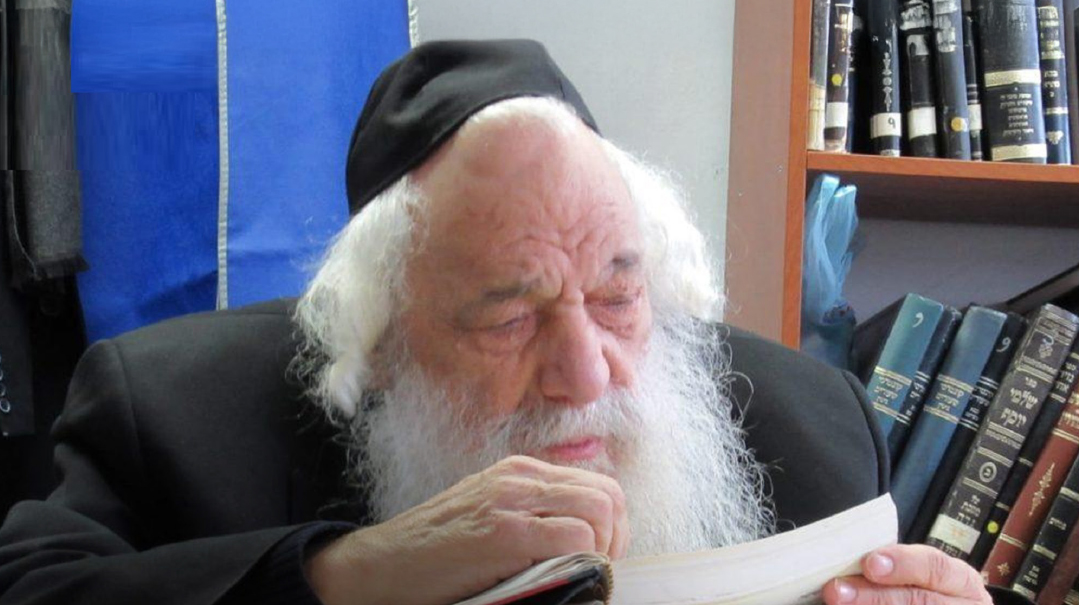

In tribute to Rav Baruch Shmuel Deutsch

Photos: AE Gedolim photos

By Rav Uri Deutsch, as told to Shmuel Botnick

In tribute to Rav Baruch Shmuel Deutsch, one of the roshei yeshivah of Kol Torah for 40 years, and more recently rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Be’er Mordechai

MY rebbi, Rav Baruch Shmuel Deutsch, hareini kapparas mishkavo, who passed away last week, was known throughout the Torah world as an illui whose vast knowledge and breathtaking speed at grasping complex issues was truly extraordinary.

Many authors of seforim presented him with their work and asked for honest critique. He would rapidly leaf through the pages and fire off questions and insights that indicated that he had fully perused and understood the content.

When editing the teshuvos of Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski, one of the greatest geniuses in the last century, he hardly ever had to consult a quoted source.

The name Rav Shmuel Deutsch has, for decades, been synonymous with prodigious genius.

But much less known is that his enormous mind came with an equally boundless heart.

It was this facet of his magnificent personality that drew me, just an insignificant bochur in Kol Torah, to have some semblance of a relationship with him.

At that time, the yeshivah had a program for “chutzniks,” talmidim who came from abroad. Understandably, being part of a small group of outsiders in a predominantly Israeli institution can feel isolating. But Rav Shmuel made a determined effort to reach out to us. He set up chavrusas for us and gave us vaadim on Friday and Shabbos.

This wasn’t done in a patronizing way at all. He was fascinated by people in general, and his heart was open to all. In his view, if someone could add another dimension of interest, he was ready to connect with them.

Rav Shmuel touched us chutzniks with his sympathy and sensitivity, just like he did to so many of his talmidim.

Because of his deep humility, I will never know the extent of what he did for his talmidim; it is only through indirect statements that he made over the course of years that I gained some insight.

I was once contemplating taking a certain teaching position. Because of the nature of the position, I recognized that significant time would need to be devoted to the talmidim’s personal needs. I was concerned — should I accept a job that would require such a commitment of personal time, which could otherwise be spent learning? I shared this concern with Rav Shmuel.

He looked at me in his totally self-effacing way and said, “What do you think I do with most of my time? I’m talking to bochurim.”

I don’t know if he meant this literally. He was more likely referring not to hours on the clock, but to the personal investment and placement of priorities.

He learned so much, knew so much.

Yet he cared even more.

Every now and then he’d let out a sigh. “Oy, this talmid is going through such a hard time. I just spent a few hours with him.”

He must have touched the lives of hundreds of talmidim, who he built and cared for, and I know that he personally collected funds for talmidim as well.

There was a point during my time in Kol Torah when I was contemplating transitioning to Ponevezh, along with a group of friends. I asked Rav Shmuel to write a letter of recommendation. He did, but then engaged in a candid discussion. He weighed the various advantages that Ponevezh might present in terms of academics but strongly encouraged me to consider the social element as well. Based on this discussion, I opted not to go.

Somewhere in my files, I still have that filled-out application to Ponevezh, along with a beautiful letter of recommendation. Per my rebbi’s instructions, I never sent it.

Rav Shmuel instead encouraged me to go to Brisk, where he himself had learned. We continued to keep in close contact. He always expressed an interest in how I was doing, and kept tabs on my progress.

This relationship lasted for decades. Whenever I needed him, he was there as a listening ear, an ocean of humility and compassion.

We once had the zechus of hosting Rav Shmuel in our home. In my mind’s eye, I can still see him sitting on the couch, without his frock, reading a bedtime story to my seven-year-old-daughter. He couldn’t read English. Instead, he was looking at the pictures and making up a story, which he shared in Hebrew and which I then translated into English.

All of this was unpretentious, not patronizing, without any aspiration to be perceived as noble.

With his enormous heart he wanted to connect, even with a young child.

In more recent years, Rav Shmuel became increasingly involved in issues deeply relevant to the olam haTorah in Eretz Yisrael. He took certain positions that thrust him into deep controversy, and I had several opportunities to discuss this with him. The content of those conversations are not relevant at this time; the point is the tone with which he expressed them. At no time — even in the most contentious of moments — was there even the slightest hint of anger or vindictiveness.

“I know I may appear as a baal machlokes,” he once told me. Then, in a most emphatic voice said, “I’m not being a baal machlokes! I feel there’s a hashkafah that has to be explained. I feel there’s a duty as a marbitz Torah to share this hashkafah. I’m explaining a sugya like I would explain any sugya in Shas.”

It was never about him. His humility ran as vast as his mind and as deep as his heart.

This humility led to another unique facet in my rebbi’s life, his absolute submission to his rebbeim. He studied in Ponevezh as a bochur, where his rebbi in terms of a mehalech halimud was Rav Shmuel Rozovsky. Much of the deeply cherished seforim that we have today containing Rav Shmuel Rozovky’s chiddushim come from my rebbi’s copious notes. He also viewed Rav Berel Soloveitchik as his rebbi from whom he learned the nuances of the Brisker derech.

And then there was Rav Shach.

He saw Rav Shach as the conduit through which we access Yiddishkeit of the previous generations. When it came to issues pertaining to the klal, his metric for “right” and “wrong” was one simple consideration: “What would Rav Shach say?”

After Rav Shach’s petirah, he turned to Rav Elyashiv as his rebbi. And then, after Rav Elyashiv’s passing, Rav Shmuel Auerbach became his rebbi.

As great a giant as he was, he always looked up to others.

But ultimately, the legacy of my rebbi is that of a man who refused to acknowledge limitations. He insisted — for himself and for everyone else — that the entire scope of Torah is ours to study, analyze, expound upon, and master.

The fact that yeshivos tend to inch their way slowly through sugyos, failing to cover significant ground, pained him to no end. At the end of each zeman, he would set up his shtender at the doors of the beis medrash, and practically cry out in pain, “We only reached daf yud zayin!” And from memory, he’d list a string of topics that we wouldn’t cover “What will be with that machlokes Ketzos and Nesivos? What will be with that Rabi Akiva Eiger?”

The system in Kol Torah was to set up younger talmidim with older chavrusas — like a mentoring structure — for Friday and Shabbos sedorim. The starting limud was Teshuvos Rabi Akiva Eiger, with the assumption that we, as 18-year-old bochurim, would be capable of comprehending this immensely complex work.

I remember my chavrusa telling me that whenever a sefer says the word “kayadua — as is known,” if he doesn’t know it, he must learn it right away.

That was the chinuch we got from Rav Shmuel. If the sefer expects you to know something — just know it. If Rabi Akiva Eiger expects you to know it — then just know it.

That was the kind of atmosphere he created around himself.

It wasn’t that Rav Shmuel expected people to be illuyim. He understood that wasn’t the case. But he did demand that we not limit ourselves. There should be no area of Torah that is viewed as obscure. You could know it, and you should know it. He felt that people’s shortcomings in learning come from their limitation in their scope of what they feel they should know.

For Rav Shmuel, all of Torah was within reach, including Kabbalah. He once told me that what attracted him to Rav Shmuel Auerbach was that “by him, kol haTorah kulah meant ‘and Kabbalah.’ ”

On Shabbos afternoons, he led a chaburah where he taught Ramban on the parshah. There, he gave us an appreciation for every word and phrase of the Ramban, which remained with me for life.

Where the Ramban wishes to express a kabbalistic concept, he prefaces it with the words “V’al derech ha’emes.” I remember once trying to debate the intention of the Ramban on one such comment.

Rav Shmuel said, “Look, I’m happy to listen, but you’re too young to talk about these things. I may need to correct you, but you’re not going to understand what I’m saying. And you might chas v’shalom think I consented to an erroneous interpretation. So let’s leave the subject alone.”

Once, to explain a kabbalistic comment of the Ramban, Rav Shmuel took out the sefer Shushan Sodos by Rav Yitzchak d’min Akko, who explains the Ramban al derech hasod. I was 19 years old at the time; even being introduced to such seforim was unheard of in the olam hayeshivos.

But he did it with no ceremony. He just said, “You know the sefer? This is Rav Yitzchak d’min Akko. You know it, yes? Let’s read it.” And he just ran down the page as one might read any Acharon. Then he turned to me and said, “So you got it, right?”

In his presence, you felt you had better become something. You must master Torah.

While he served as a rosh yeshivah, and spent his day studying and teaching sugyos b’iyun, Rav Shmuel also had a great interest in halachah seforim and was fluent in hundreds of sh’eilos u’teshuvos seforim. He once shared that he has a special fondness for the seforim of the early commentaries of Sepharad, such as the Mishneh Lamelech, Sha’ar Hamelech, and Teshuvos Maharit, which tend to have a more structured, contained analysis than the sweeping pilpul found in Ashkenazi commentaries.

The degree to which Rav Shmuel was demanding of himself defies comprehension.

There is no Talmud Bavli on Sidrei Zera’im and Taharos and, for this reason, these sedorim tend to get neglected. An off-hand comment he once made revealed the degree to which he expected himself to gain full mastery over these areas of Torah.

It had come time for me to consider leaving full-time kollel in search of a teaching position, and I approached Rav Shmuel to discuss the various pros and cons. One primary concern was that leaving kollel meant sacrificing the ability to learn in a most ideal setting.

Rav Shmuel looked at me and said “You think I didn’t give something up? I gave up Zera’im and Taharos! I don’t know it as well as I could have.”

Context is important. Rav Shmuel was one of the few talmidei chachamim entrusted by Rav Shneur Kotler to edit — or practically write — the brilliant chiddushim of his father, Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l. Rav Shmuel was tasked with working on the chiddushim on Zeraim and Taharos.

To successfully complete this task required absolute clarity in these topics.

And yet this is what Rav Shmuel considered his “weak spot” — the areas of Torah that he “gave up” for the sake of teaching talmidim.

In his later years, one of the things that Rav Shmuel decried was that maggidei shiur, by accepting a teaching position, may limit their aspirations to the topics expected of them to teach.

Rav Shmuel was determined to challenge this perception. He opened a second-seder kollel where he virtually demanded of maggidei shiur to devote their second seder to other areas of Shas. A number of volumes of his seforim, Birchas Kohein, emerged from the sessions learned in that kollel.

Rav Shmuel’s petirah leaves us with a void once filled by a man who lived with no limit to his horizons. His message to us all is to negate any voice of inner discouragement. The sentiment that “this masechta is too hard,” or “this sugya is too obscure” was nonexistent in his world.

And with his entire caring heart and his brilliant mind, he demanded us all to feel the same.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1075)

Oops! We could not locate your form.