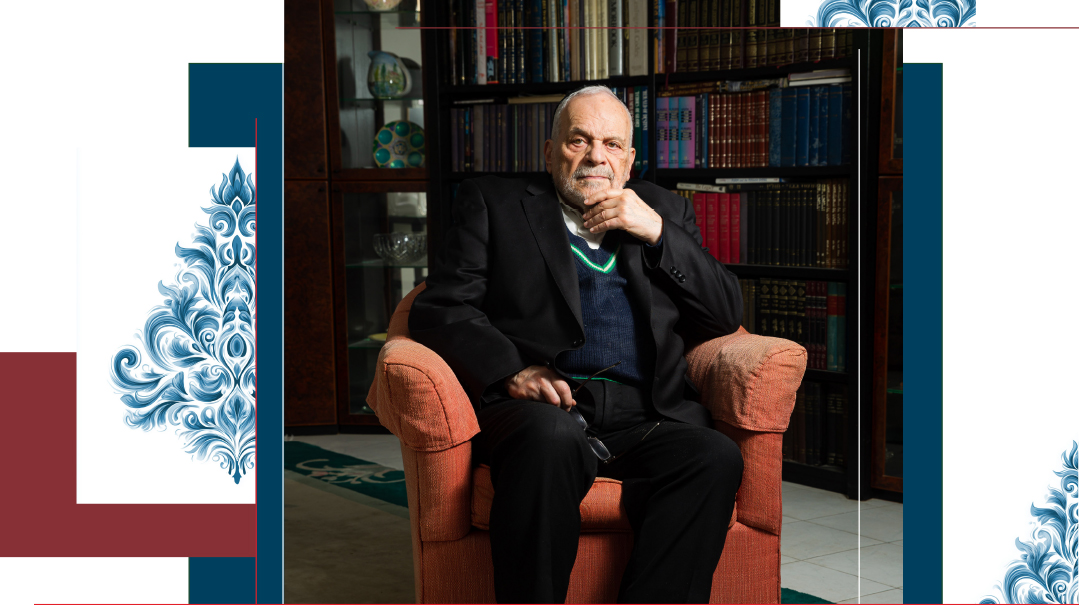

One Family

| August 19, 2025What made Rabbi Wein’s quips timeless was their economy. He didn’t need a paragraph; he needed a line. He didn’t need theatrics; he needed timing

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha and family archives

A

fter my father, Rabbi Dr. Samuel I. Cohen, was niftar, my mother, Mira Cohen, eventually remarried — and the man who stepped into that role was none other than Rabbi Berel Wein. What followed was a relationship that was not guarded or conditional, but genuine and overflowing with warmth. We called him Zaydie Berel, and he embraced us as though we were his own children and grandchildren.

At the bar mitzvah of our son, Zaydie Berel rose to speak. And in a moment that startled me with its grace and selflessness, he chose not to highlight himself, but to focus instead on my father, and his extraordinary contribution to Klal Yisrael as a frum executive vice president of the Jewish National Fund (JNF). It was a class act in every sense. Many men might have subtly recentered the moment on their own role in the family, or sidestepped the memory of the man who came before them. Zaydie Berel did the opposite. He honored my father’s legacy openly and warmly, in front of a room filled with family, friends, and community. That gesture said more about his character than any introduction could have. It showed us that he was not competing with my father’s memory — he was embracing it.

We quickly learned that Zaydie Berel was the master of the zinger. To speak with him was to spar with a master.

What made Rabbi Wein’s quips timeless was their economy. He didn’t need a paragraph; he needed a line. He didn’t need theatrics; he needed timing.

Take this classic on Jewish unity: “If two Jews agree on everything, then one of them is unnecessary.”

Or this one on synagogue politics: “In every shul, there are people willing to give up everything for Judaism — except their seat.”

Or this insight on marriage: “They say marriages are made in Heaven. So are thunder and lightning.”

But his litvishe wit was never ornamental. It was both armor and compass — armor against folly, pomposity, and narishkeit, and a compass pointing unfailingly toward truth. You’d recognize that what seemed like a passing remark had been mussar in miniature — a seed planted in silence, destined to grow.

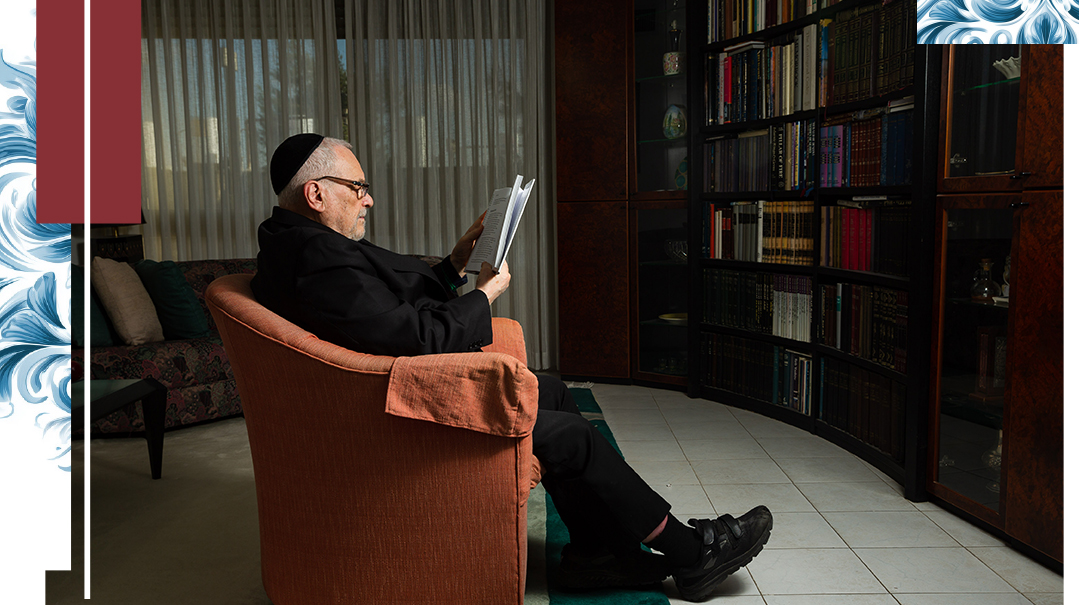

My initiation to that sharp wit took place when he came to Los Angeles before getting engaged to my mother. Visiting my home, he drifted toward my bookshelf as if by instinct. His finger moved across the spines like a dayan reviewing evidence — scanning, measuring, weighing the scene with quiet authority. And then he stopped. Not a single Berel Wein sefer in sight. He turned to me, eyebrow arched and then, with the precision of a cross-examiner who already knows the fatal answer, he delivered a single word: “Seriously?” That was it. Just one word.

And then, with the precision of a dayan issuing a second, decisive tap, he doubled down: “You live in Los Angeles — home of Hollywood, the land of fake facades. You could have at least created fake facades for your library.”

Each time Zaydie Berel visited Los Angeles, he arrived with one of his newest books in hand, always with a warm handwritten note inside — not merely a gift, but a statement. As those seforim filled my shelves, I came to understand what he had really planted there: not just volumes of words and wisdom, but a lifelong lesson — that Torah is never a facade. It must be lived, displayed, and owned with integrity, not only on the shelf, but in the heart, the home, and the soul.

Zaydie Berel often described himself — half in jest, half in truth — as a recovering lawyer. Though the pulpit and the pen became his great arenas, the instincts of an attorney never left him. That legal background gave him a special delight in following my litigation cases, because he saw in litigation the same intellectual chess match that had once animated his own legal work. For him, it was never just about who won or lost — it was about the craft of the argument. When I described a carefully laid brief, a surgical cross-examination, or a strategy that forced the opposition into retreat, his eyes would twinkle with recognition.

When I told Zaydie Berel about the polygraph experiment I participated in, and how the FBI agent declared it could not be fooled, because deep down a person knows truth from fiction, Zaydie Berel leaned back with that half-smile that always signaled a message was coming: “Just like the polygraph knows the truth, so does the neshamah.” For him, the analogy was seamless. Machines may detect changes in pulse and breath, but the soul — our innermost self — is the truest lie detector of all. We may excuse, rationalize, or spin our actions, but deep inside, the neshamah registers every falsehood and every truth with perfect clarity. That was vintage Zaydie Berel: turning a courtroom anecdote into a spiritual insight. What the FBI agent stated as science, he elevated into mussar.

For all his wit, his sharpness, and his fearless honesty, to us he was never just the great Rabbi Wein — he was Zaydie Berel. My wife and I cherished him not as a public figure, but as the heartbeat of our family. He was our anchor, our sounding board, our teacher, and our comfort. Our children adored him, soaking in his stories, his warmth, and the sparkle in his eyes when he turned a phrase or delivered a zinger with perfect timing. He had the rare gift of making each of us feel seen, valued, and loved — not in sweeping declarations, but in the quiet strength of his presence, in the subtle wisdom of his words, and in the deep pride he carried for his family.

Even after my mother’s passing, Zaydie Berel continued to show up for our family — literally. He traveled from Israel to attend our simchahs, making the long journey not out of obligation, but out of love and loyalty. This was no small matter. International travel is draining even in the best of circumstances; for a man of his age, stature, and schedule, every day at home was precious. Yet when it came to celebrating our milestones — a wedding, a bar mitzvah, a special occasion — he came. He walked into the room not as a distant dignitary, but as family. He greeted our children and grandchildren with the warmth and familiarity of a true Zaydie. That, perhaps, was the most extraordinary part. There was no halachic or familial requirement binding him. My mother was gone; the technical tie was severed. But his bond with us wasn’t built on technicalities. It was built on relationship, respect, and genuine love. In a world where relationships often fade when the connecting link is lost, Zaydie Berel’s presence was a living testament to his character. His actions said: I was here when we were one family, and I am here still — because to me, we still are.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1075)

Oops! We could not locate your form.