Refracted Light

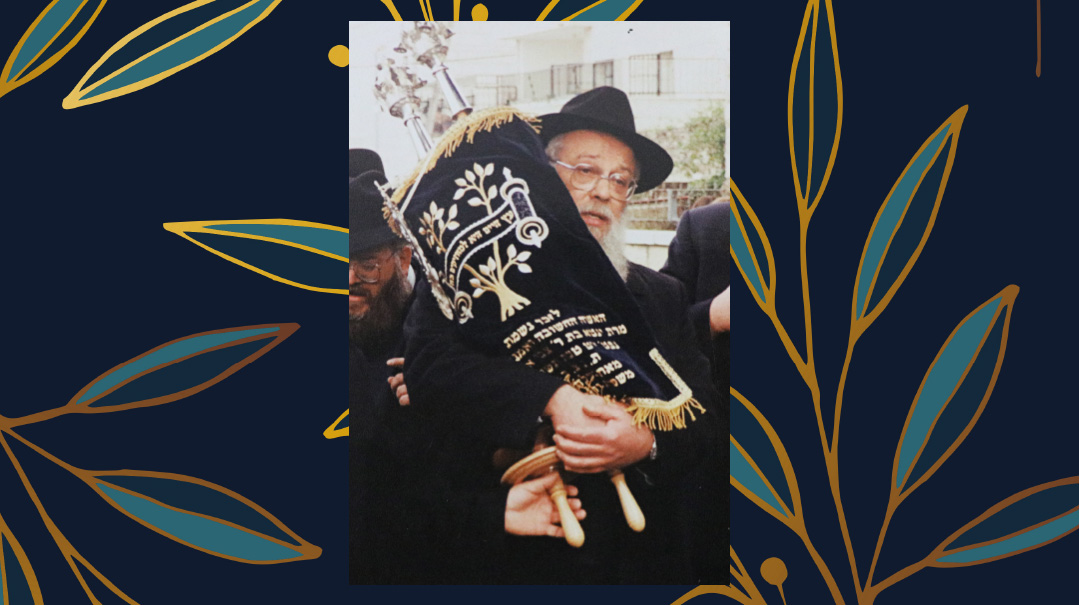

Ner Moshe’s Rav Avrohom Gurewitz was a guiding beacon through shifting generations

Photos: Yeshivas Ner Moshe and family archives

Rav Avrohom Gurewitz, rosh yeshivah of Ner Moshe and prolific mechaber of the Ohr Avrohom series and more, was in his late eighties, still going strong, still learning and writing seforim, when — recovering from a hospital stay and about to return home — he was suddenly gone, the open notebook on his desk bearing witness to his latest work. Yet he left in his wake a million sparks that he personally ignited, encouraged, and fanned

And if I have merited to express some theory or understanding in words of Torah, or to find some novel concept in the words of the Rishonim and Acharonim which, if written, will be helpful to others, then it is certainly my obligation to do so. And through this I, too — Avrohom, descendant of Avraham Avinu — will merit to somewhat illuminate the darkness and obscurity that covers the earth, as long as we are placed in the world of tohu vavohu in this bitter exile.

These words are written as part of the introduction to the sefer Ohr Avrohom, by Rav Avrohom Gurewitz ztz”l, on sugyos haShas. The essay begins by quoting the midrash which teaches that the words “yehi ohr — let there be light” refer to Avraham Avinu.

Avraham Avinu was the very definition of light.

Why is this?

Rav Gurewitz suggests that it’s because Avraham Avinu didn’t just learn Torah.

He taught Torah.

He let others see the brilliance that he himself perceived.

He brought the masses into his world.

He shared, he cared, he sacrificed, and he taught, taught, taught.

And that, says Rav Gurewitz, is the very personification of light.

Rav Gurewitz was also named Avrohom, and he saw it as his obligation to model himself after the patriarch of our People.

His mission was to spread light.

For over five decades, Rav Avrohom Gurewitz taught Torah in various settings and institutions. He himself was a relentless masmid, learning all day and deep into the night, possessing encyclopedic knowledge of the gamut of Torah. His 23 volumes of chiddushim, all titled Ohr Avrohom, are each jammed margin to margin with his writings, running for some nine hundred pages. But learning alone wasn’t enough. He had to spread light, and so he invited thousands of others to join him in the world he loved so much.

It can’t be a coincidence that when he opened a yeshivah and named it after his father, Rav Moshe Gurewitz, he chose to call it “Ner Moshe — Moshe’s Candle.”

Upon this candle he cast a light.

Last Thursday, without notice, this light suddenly extinguished in a wisp of smoke. Rav Avrohom Gurewitz, rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Ner Moshe, had been in the hospital for a week, receiving treatment for pneumonia. He was recovering, readying to return home, and then… he was gone.

He left this world in a whisper, leaving in his wake a million flashes of light that he personally ignited, encouraged, fanned until they reached independence.

Ad shetehei shalheves oleh m’eilehah — until the flame can rise by itself.

And those flames will continue to shine with the Torah that he spent a lifetime teaching.

Palestinian in Ponevezh

Rav Avrohom was born in Yerushalayim, on the sixth of Elul, 1937, prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. With his typical wry sense of humor, he would call himself a “Palestinian.” He was just a little boy when his father, Reb Moshe, traveled alone to America to seek employment, where he succeeded in securing a position as a rav in New York. He then sent for his wife, Chana, and their three children.

It was the winter of 1941, while World War II was still raging, and the usual westward route through the Mediterranean and across the Atlantic was too dangerous. Instead, they went east, ultimately arriving at a port in California. Their arrival was featured in an article in the Los Angeles Times.

A close look at the picture shows that Avremel had long locks of hair. While his third birthday had been several months prior, his mother held out on cutting his hair, choosing to wait so that his father, Reb Moshe, could be the one to oversee the traditional upsheren. Also visible in the picture is the yarmulke clamped upon the thick tufts of hair. Many years later, when Rav Avrohom published his first sefer, he brought it to his parents. His mother turned to her husband. “I’m taking the credit,” she said. “Ever since he was born I kept a yarmulke tied onto his head with a string. That’s what allowed him to become what he is today.”

He attended Torah Vodaath and then Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin. In 1958, at the advice of his father, he left New York to join Yeshivas Ponevezh. It was there that he met the man who would become his rebbi for life.

For decades to come, Rav Avrohom would speak about Rav Shach. He saw the world through the prism of his rebbi’s approach, clinging to the raw, unadorned, yet majestic spirituality of prewar Lithuania.

Rav Avrohom was resolutely independent, unaffected by any external feedback, whether positive or negative. The one exception was Rav Shach. He glowed when he shared memories of the deep affection Rav Shach had for him.

“Rav Shach sat in the back of the beis medrash, and bochurim often went over to speak with him in learning,” he would share. “A few weeks passed where I didn’t feel I had what to speak to him about. One day, he walks over to me in the beis medrash and says ‘Zeit broiges oif mir? Are you upset with me? Where have you been?’ ”

It wasn’t only Avrohom’s Torah that Rav Shach cherished.

As a rosh yeshivah, Rav Avrohom, always brilliantly witty, had a most creative method of waking up the bochurim for Shacharis. If he noted bochurim were missing from the beis medrash after davening had started, he would head into the dormitories, water gun in hand. He would approach a sleeping bochur, steady his arm, and shoot a well-aimed squirt, startling the boy out of his slumber.

Once, on a fundraising trip to America, he shared this technique with a close talmid, Dr. Yaakov Finestone. Mrs. Finestone, who was present, asked, “Is that what they did to you in Ponevezh?”

Rav Avrohom shook his head. “Oh, no. In Ponevezh, I once missed Shacharis. Rav Shach came over to me and put his hand around my shoulder. He said ‘Avrohom, I missed you. Davening wasn’t the same without you.’ ”

“Doesn’t the Rosh Yeshivah think that method worked better than the water gun?” Mrs. Finestone wondered aloud. Rav Avrohom was quiet for a moment, then nodded slightly. He had to head to the airport for his flight back to Eretz Yisrael.

Two hours later, the phone in the Finestone home rang. It was Rav Avrohom, wishing to speak with Mrs. Finestone. “I thought about your question,” he said. “You’re right. Rav Shach’s method was better than mine.”

Rav Avrohom would describe what learning in Ponevezh was like. “On Erev Shabbos, we learned until one hour before shkiah. On Motzaei Shabbos, we began learning the moment after Havdalah.”

The overseas communication was nothing like it is today. Rav Avrohom shared how he wrote weekly letters to his parents, while reserving a time to use the telephone once a year — prior to Rosh Hashanah.

After spending three years in Ponevezh, in 1961, Avrohom returned to America and rejoined Chaim Berlin. Not long after, he announced his engagement to Tzirel Bernstein, the daughter of Rav Binyomin Bernstein, who had studied in the Kamenitz yeshivah under Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz ztz”l.

Tzirel, known to thousands of talmidim as “Rebbetzin,” was every bit as dedicated to her husband’s talmidim as he was. She was the sweetest of personalities, always smiling, forever cheerful, ready at any moment to help any talmid, all of whom she knew by name.

Once married, Rav Avrohom joined Chaim Berlin’s kollel, Kollel Gur Aryeh, where he learned for five years. He then joined Reb Zelig Meir Kanter in forming a yeshivah called “Romema.” The Gurewitzes, however, always intended to move to Eretz Yisrael and in 1970, the dream became a reality. They bought an apartment on paper in Yerushalayim and settled in Bnei Brak until it was ready.

Rav Avrohom had nothing set up in the way of employment, but he had full trust that Hashem would send him a job. That happened fairly quickly. Rav Avrohom went to visit a former talmid who was learning in Itri yeshivah in Beit Safafa, at the southern edge of Yerushalayim. The talmid introduced him to his rosh yeshivah, Rav Mordechai Elefant, and the two developed an immediate rapport. He was offered a job on the spot which he accepted.

Ultimately, the family moved to Yerushalayim, and Rav Avrohom continued to teach in Itri for several years, before moving on to a yeshivah called Mishkan Torah.

But inwardly, he yearned to use his rare gifts to help mold boys in the way that only he could. It was 1984; his father, Reb Moshe had passed away in the month of Teves. In Iyar of that year, Rav Avrohom founded a yeshivah of his own, and named it Ner Moshe, after his father.

Together with his close friend, Rav Shalom Schechter, Rav Avrohom led the yeshivah through three iterations. From 1984 to 1995, it catered to a diverse student body, hailing from across the academic and hashkafic spectrum. He then closed this institution and formed a kollel that lasted until 2005. Then, he reopened the yeshivah in the model which it exists today, welcoming bochurim from leading American yeshivos to learn Kodshim in the traditional style of Brisk.

In the yeshivah, Rav Avrohom blended brilliance, wisdom, sarcasm, hilarity, and wit to create an environment defined by the joy and exhilaration gained through a life devoted entirely to Torah, Torah, and more Torah.

He would see miraculous success in his work; Even the yeshiva’s location was secured through a miracle.

The day the scheduled closing for the yeshivah’s current building in Givat Shaul, Rav Avrohom was still several thousand dollars short of the amount required for a down payment.

“Do you think I slept that night?” he asked while retelling this story. “Of course I slept! I slept like a baby. Why should I lose my building and my sleep?”

The next day, he got a frantic call from his daughter. “Abba, I was driving by the building and I saw bulldozers demolishing a part of it!” The building was owned by two brothers who were in some sort of machlokes, and as a result, two small auxiliary structures attached to the building were demolished, exactly that day.

Rav Avrohom called his attorney. “This wasn’t part of the deal!” he said. “The down payment included those structures as well. If you knock them down, then the down payment must go down as well!”

The argument worked, and the down payment price was negotiated downward, to one Rav Avrohom was able to afford.

All My Sons

Rav Avrohom strongly opposed the approach of expecting bochurim to fend for themselves in terms of room and board. He would explain that a yeshivah must take the role of both father and mother. A father is charged with seeing to his child’s spiritual development while a mother must see to the child’s physical wellbeing.

“As a yeshivah, we are both an av and an eim,” he said proudly. “We make sure to have the best food and excellent dorming accommodations.”

Until today, a hallmark of Ner Moshe is that it offers ideal material provisions to complement its premier spiritual environment.

Like a parent, he took so much pride in his talmidim. On Purim, after Krias Megillah, he would leave the yeshivah and return to his home in Ramat Eshkol, quite a distance away. But later he would go back to join the bochurim dancing as they celebrated Purim.

“Why would the Rosh Yeshivah come all the way back?” he was once asked.

“My bochurim are having a mesibah and I shouldn’t join?” he responded.

The relationship he had with his talmidim wasn’t limited to the structure of learning, teaching, asking, and answering. He loved his talmidim and simply enjoyed their company. Bochurim could spend hours in his spacious office lined with large glass windows, discussing anything on their minds. When a talmid presented Rav Avrohom with a fish, feeling that a fish tank would add a perfect touch to the office’s decor, Rav Avrohom was thrilled. In the spirit of the yeshivah’s Kodshim curriculum, he named it “Piggul” (referring to the status of a korban sacrificed with the wrong intentions).

Once, as Rav Avrohom left the yeshivah sometime around midnight, he spotted a close talmid. “You’re here all day and you don’t have time to visit the old man upstairs and say hello?”

When Rav Avrohom first opened the yeshivah, he delivered a shmuess. “I don’t care if you pay full tuition or no tuition,” he said. “If you’re learning, you can ask me for whatever you want.”

When a bochur’s parents got divorced, he approached Rav Avrohom and explained that there was no longer anyone to take responsibility for his tuition payments.

“If the Rosh Yeshivah has to, he can send me away from yeshivah,” he said. Rav Avrohom shook his head. “No, stay,” he said. The following day he handed the boy an envelope. It contained $500.

In the earlier days of the yeshivah, Rav Avrohom made frequent trips to America to raise money. An alumnus once asked him, “Why does the Rosh Yeshivah have to work so hard fundraising? Why not just make a policy that only boys whose parents pay full tuition can come to yeshivah?” Rav Avrohom blanched. “I should turn away a bochur because his father can’t afford tuition?”

“Well,” the talmid persisted, “what about those bochurim who fathers could pay full tuition but refuse to do so? At least those bochurim should be rejected!”

With his classic smirk, Rav Avrohom shot back. “I for sure should not reject a bochur for his father being a nuisance!”

He was brilliant at using his unparalleled skills to provide all that he could, but even more brilliant, and courageous, was recognizing that which he could not provide. When he closed Ner Moshe in 1995, he gave a shmuess. He explained that one of his intentions in this dramatic move was that he felt that he no longer could offer a critically needed service at that time. It was always Rav Avrohom’s desire for all to feel welcome in the yeshivah — even those not yet oriented with full-time Torah study. He reveled at the opportunity to engage these boys in intellectual discussions and show them the joys of Torah. But as drug usage became more prevalent, he concluded that no intellectual conversation can counter the lure of artificially induced euphoria. He forecasted this to be the challenge of upcoming times and felt that it wasn’t one he could rise to.

If he couldn’t provide what was needed, it was time to step down.

Eyes to See

Rav Avrohom often returned to yeshivah from his fundraising trips armed with stories of experiences he had on the airplane or in the airport.

“Rosh Yeshivah,” a talmid asked, “I also travel to America. Why don’t I have stories?” Rav Avrohom smiled.

“You have to open your eyes,” he said. “If your eyes are open you see stories everywhere.”

This very much captured Rav Avrohom’s approach to life. He was a keen observer of society, saw snippets of mussar everywhere, and knew just when and how to express these latent messages.

He once pointed to his fish, Piggul. “Look, he said, “the fish is constantly opening his mouth. It opens and closes, opens and closes.

“You know what we learn from this?” Rav Avrohom said. “The fish doesn’t talk when it opens its mouth. That’s the lesson. Not every time that you open your mouth do you have to say something.”

In 2015, rare footage of the Chofetz Chaim at the first Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna was discovered and made public. Rav Avrohom saw a Divine message in this. “Specifically in our time, the image of the Chofetz Chaim resurfaces,” he said. “Look around. Everyone is on cell phones. Everyone’s talking. Now, more than ever, we need to internalize the message of the Chofetz Chaim.”

He once approached Aaron Solomon, a close talmid, and posed a question. At the end of Shemoneh Esreh, in Elokai Netzor, we daven that Hashem should “protect my tongue from bad, and my lips from speaking deceit.”

“Why specifically this tefillah?” Rav Avrohom asked. “Why is it so important, specifically as we complete Shemoneh Esreh, to daven for protection with our speech?” Rav Avrohom then suggested an answer.

“When we begin Shemoneh Esreh, we ask Hashem, ‘sefasai tiftach, open my lips.’ We entreat Hashem to open our mouths so that we can express words of tefillah. But,” Rav Avrohom said, “the moment we complete davening, it’s time for the mouth to close. We turn to Hashem and say ‘Now that we’ve finished davening, help me close the mouth that I previously asked you to open.’ ”

On visits to the United States, Rav Avrohom would go on various trips with talmidim. He once took Zvi Lang to an ancient beis hakevaros in Upstate New York. As they exited the car, Rav Avrohom pointed to the ground. “Hey what’s that?” Zvi squinted. “It’s a penny.”

“A penny? Pick it up!” Rav Avrohom said. Incredulous, Zvi retrieved the penny and handed it to his rebbi.

They davened by the kevarim and then continued on to their ultimate destination, a seforim store, whose owner had an arrangement with Rav Avrohom to buy his seforim at wholesale prices.

After concluding the sale, they returned to Brooklyn.

The following day, Zvi saw Rav Avrohom leafing through a stack of papers. “A few days ago, I had trouble with my car,” he said. “I brought it to the mechanic and I’m looking through the bill.” He looked at Zvi. “It’s the exact amount of money we made selling the seforim — plus one penny.” Then he broke into a smile. “That was the penny we found!”

He didn’t hesitate to tell his talmidim what he thought they needed to hear. He was on a fundraising trip when he visited a talmid’s home. This talmid had recently sent him a thousand dollars to help finance the publishing of one of his seforim, and Rav Avrohom wished to thank him in person. When he entered the home, though, he saw on the wall a screen that he later described as “so big I thought they were going to hand out popcorn.”

Rav Avrohom turned to the talmid. “Why do you have a relationship with me?” he asked rhetorically before continuing. “Because you want a rebbi. My rebbi was Rav Shach. His rebbi was Rav Isser Zalman. That’s the mesorah I’m trying to give over. Now, I give you one week to decide who your rebbi will be. Me or,” he pointed to the screen. “It?” .

A week passed, and Rav Avrohom had not heard back from the talmid. He took out ten one-hundred dollar bills and put them in an envelope along with a letter. Then he then drove to the talmid’s home and slipped the envelope under the door.

The story ends with an incredible postscript.

“Within 24 hours,” he shared, “I received a call from a talmid I hadn’t spoken to in years. He asked me to come to his office, where he handed me a check for eighteen thousand dollars.”

“You see,” Rav Avrohom said, “when you do the right thing, Hashem pays you back kiflei kiflayim.”

He had a way of communicating basic messages in the most memorable of fashions.

A bochur placed his hat and jacket on the bimah in the beis medrash, where it remained all day, until it came time for Rav Avrohom to deliver his weekly shmuess. He stood at a shtender that was placed before the bimah and began to speak about “Derech eretz kadmah laTorah.” He then stopped short, reached across the bimah, and grabbed the hat. “And this — leaving a hat and jacket on the bimah — you call this derech eretz?!” He cocked his arm and let the hat sail, frisbee-style, across the room.

Derech eretz is a prerequisite to Torah, and the lack of it bothered him immensely.

Rav Avrohom was in America, fundraising on behalf of the yeshivah, and was visiting his close talmid, Yossi Kunstlinger. Yossi noticed that his rebbi looked upset, and asked him what was on his mind.

Rav Avrohom shared how he had recently visited a group of talmidim. In the midst of the conversation they voiced something to the effect of “we don’t need to show hakaras hatov to the yeshivah because our success was due to our own diligence. It wasn’t anything that the yeshivah did for us.”

“I don’t understand,” Rav Avrohom said. “Why can’t you have gratitude? It will cost you money? I don’t want your money. But show some appreciation to a yeshivah in which you grew.”

“Let’s say they’re right that their growth came from their own initiative,” he added. “Does that exempt them from hakaras hatov? They should be grateful to the environment in which they saw success.”

Rav Avrohom would call talmidim in at random, to address whatever might be on their minds. He once called Yehuda Russak to share an idea from the Gra with him. In Megillas Rus, Rus pleads with Naomi to allow her join Am Yisrael, but at first, Naomi demurs. Then the pasuk continues, “Vateireh ki misametzes hi laleches — She [Naomi] saw that she [Rus] was strengthening herself to go.” At this point, Naomi allows Rus to join her.

“What’s the continuum?” asked Rav Avrohom. How does Naomi “seeing Rus strengthen herself” lead her to change her mind so drastically?

Rav Avraham then looked at Yehuda meaningfully.

“The Gra explains that what Naomi saw was Rus struggling. If Rus was struggling that means it was the right thing for her to do. Doing the right thing always comes with a struggle.”

“I was once complaining to the Rosh Yeshivah about something,” says Rav Dovid Rube, rav of Beis Medrash Ateres Rosh in Monsey and a close talmid of Rav Avrohom. “I said something to the effect of ‘Sometimes, I want to jump off the grid and park myself in a corner and learn.’ ”

Rav Avrohom’s response was concise.

“Dovid, you wanna do what’s easy or you wanna do what’s right?”

It’s often not the same thing.

The Hidden Light

Rav Avrohom wrote in his introduction to his seforim that he saw it as a responsibility to live up to Avraham Avinu’s description as “yehi ohr.”

But there’s something interesting about this light. We never truly saw it. This original light, the Ohr Haganuz, was tucked away, awaiting its chance to shine some time way off in the future.

For now, we only see little glimmers peeking through the dense curtains.

Rav Avrohom was indeed a brilliant light, as anyone who has glanced through any of his 23 seforim can attest. Yet nothing about his persona, attire, or presentation revealed any of this greatness. He wore a short jacket and a down hat; his demeanor was entirely approachable; and his style of speech was unpretentious, warm, and always laced with humor.

His eyes always laughed, a small smile tugging at his lips. It was as if he were laughing at the world, seeing past the veneer that obstructs so much and confuses so many.

He davened in the Mishkan Esther shul in Sanhedria, where he had a seat in the back. “Yeah, they always try to get me to sit in the front,” he said. “My wife wants me to listen to them. I tell her,‘Here, I have a window next to my seat. Up front, it’s so hot and stifling.’ ”

In June of 2023, Ner Moshe held a special dinner in honor of its 40th anniversary. Rav Avrohom was called up to speak, and the emcee used the term “Harav Hagaon Rav Avrohom Gurewitz.”

Rav Avrohom rose to the podium and leaned toward the microphone. “I just want to talk about the olam haTorah nowadays,” he said. “A few thousand years ago, we had Tannaim. Then we had Amoraim. After Amoraim we had Geonim. You know why they were called Geonim? Because they knew all of Gemara backward and forward. Since then, there haven’t been geonim. Until today! Now, everyone is a gaon!”

He continued his speech and then concluded by introducing the next speaker, Ner Moshe’s much-beloved maggid shiur, Rav Yankel Lieberman.

“I would like to introduce Rav Lieberman shlita. And you’ll forgive me if I don’t call you Harav Hagaon….”

Gift of Sight

Many years ago, Rav Ahron Soloveichik z”l, who then served at maggid shiur in the tenth grade of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin, faced a dilemma. There was a bochur in his shiur who had been born sighted, but later, tragically became blind. Finding this boy a chavrusa willing to navigate this obstacle would be very difficult. One bochur, Avrohom Gurewitz, stepped up to the task. He became chavrusas with the boy; together, they journeyed through the pages that one could see and the other could not.

Later, Rav Soloveichik commented that while Avrohom was a good bochur before this, his rapid vertical ascension in Torah happened after he became this boy’s chavrusa.

After Rav Dovid Rube heard this anecdote, he asked his rebbi about it.

“Is this true? Did Rebbi experience special hatzlachah during that zeman?” Rav Avrohom thought for a moment. “It was definitely a special experience,” he said finally. “But let me tell you why. This bochur didn’t just want me to read the Gemara to him. He wanted to visualize it. He wanted to see exactly where each Rashi was, where each Tosafos was. And so I had to teach the sugyos in a way that he could see the Gemara and Rishonim before his very eyes.”

Yehi ohr.

Let there be light.

When light is strong enough, sight can be brought to the sightless.

And today, thousands of talmidim perceive what Rav Avrohom saw all along.

Plan B for Every Bochur

Rav Menachem Nissel

The year was 1979. We were three Brits enjoying a year or two in yeshivah before embarking on our careers. Eliot Stefansky and I were heading to medical school while Yossie Davis was off to Cambridge. In other words, Plan A meant that the only way you would read my writing is if you were stuck in London and needed a prescription for cough medicine.

We wanted high-level learning so we temporarily traded our kippot srugot for black kippahs and went to Itri Yeshivah, famous for its world-class teachers. It was located in the sleepy Arab village of Beit Safafa at the southern edge of Yerushalayim. We were introduced to our rebbi for the year, Rav Avrohom Gurewitz. He was known as a straight shooter from Brooklyn and a talmid of Rav Yitzchak Hutner and Rav Shach. Little did we know that Plan B had been unleashed.

The first thing we noticed was that he was different. He sat in the back corner of the beis medrash while the other rebbeim adorned the Mizrach. He occasionally wore blue shirts and made no secret that he had a subscription to Time magazine. He was the type who for “personal reasons” would not get haskamos for his seforim, but at the back of his sefer you would find a glowing haskamah from Rav Moshe Feinstein inserted “at his father’s request.”

His shiurim were mesmerizing. We would watch him through a haze of cigarette smoke as his tall figure, standing hunched over a shtender, tore apart the sugya we had just spent hours preparing. He would then rebuild the sugya, with scintillating brilliance, and everything fell into place.

He loved telling jokes. They were actually funny, not the rebbi version of “dad jokes,” they were the type that I would scribble in the margins of my notebook next to the write-ups of his classes. His deep gravelly voice would laugh heartily at everything that amused him while his eyes danced in delight.

He was a master mechanech. He dared us to believe in our greatness. I once asked him a question on a Sfas Emes, and he casually responded that he had the same question, “So it’s two against one, so we’re probably right.” He was ruthless when we said a weak argument or asked a dumb question, but he rebuked us in a way that empowered us to do better.

One day I asked him what his game plan was. Was he trying to change our hashkafos? He knew the world where we came from and I argued that the chareidi world would never be suitable for our background. With a twinkle in his eyes he responded, “Menachem, don’t worry, I’m not going to make you black. But I’m gonna make you charcoal gray.”

One day he arrived at our dorm at four o’clock in the morning. He piled us in to his sand-colored Peugeot 404 station wagon and we headed toward the Dead Sea, davening vasikin in Ein Gedi. Afterward we swam in the Yam Hemelach and were back at 9 a.m. for morning seder. He made us promise that we would push ourselves to learn well that day. The experience was undiluted fun, but the result was that rebbi was no longer just someone whom we deeply respected. We loved him with our hearts and souls.

The years rolled by. We moved from Itri to Mishkan HaTorah (playfully known as “Splitri”) and eventually we went our own ways. Eliot learned in Brisk and became Rav Elozor Stefansky, rav of the Vine Street Shul in Manchester. Yossie learned in Reb Zvi Kushelevsky’s and became Rav Yosef Davis, senior editor of the ArtScroll Talmud. And Rebbi? He got rid of his blue shirts and his subscription to Time magazine and became rosh yeshivah of Ner Moshe in Givat Shaul.

For four decades he built countless talmidim and wrote 23 Ohr Avrohom seforim on every conceivable topic. Some described him as a humble man, but my experience was that he just had a visceral hatred of shtick, including anything to do with kavod. He was known as a masmid, but I think he just loved learning so much, you just couldn’t take him away from his seforim. Nothing made him happier than finding an obscure Rishon to make his point. Nevertheless, he found time to come to our family simchahs.

At his levayah, his son Binyomin used Yaakov’s ladder as a metaphor for his legacy. His head was in the clouds, but his feet were firmly entrenched on the ground. He related to everyone on their own turf. He had a Plan B for all his talmidim. Our first impression of him endured — he was different. In today’s language he would have been called “authentic.”

And Rebbi was right, I ended up charcoal-gray. With just a tinge of black.

Rav Menachem Nissel is a rebbi at Yeshivas Yishrei Lev, Senior Educator at NCSY, and the author of Rigshei Lev: Women and Tefillah (Feldheim 2024).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1074)

Oops! We could not locate your form.