Time for Some Good News

There was plenty of negative news about Jews and Israel still left to discuss this week. But with the end of the Three Weeks, I decided to give it a break

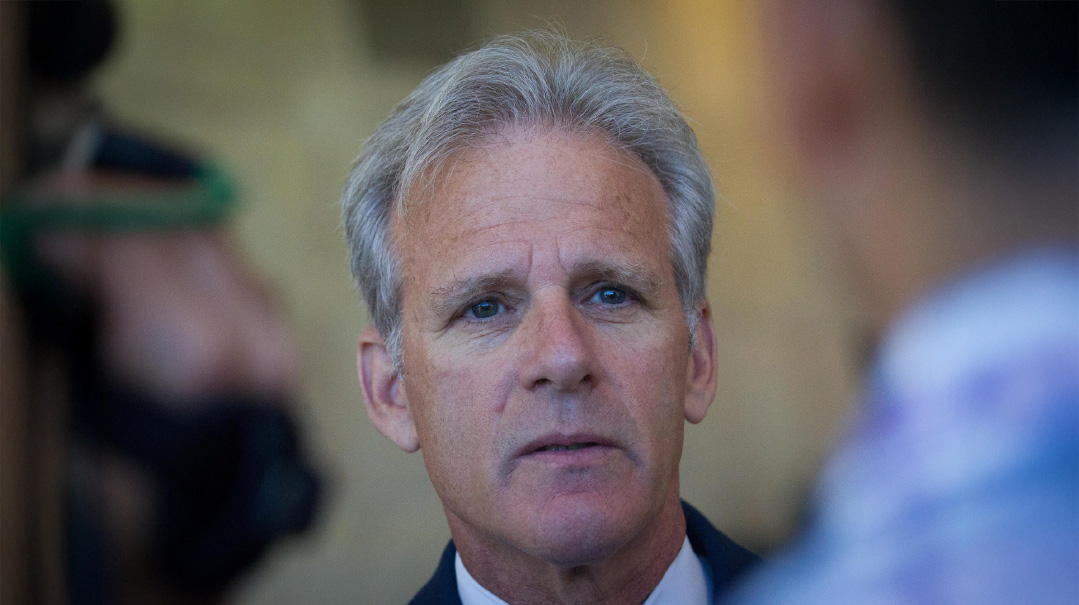

Photo: Flash90

F

ormer Israeli ambassador to the US Michael Oren speculated last week on possible parallels between the aftermath of the 1967 Six Day War and Israel’s current war with Iran and its proxies. He is well qualified for the task: His Six Days of War: June 1967 and the Making of the Modern Middle East is considered the premier history of the Six Day War and its aftermath.

Even though Egypt would again launch an invasion against Israel in 1973 and it would be ten years after the Six Day War until Anwar Sadat visited Israel and began negotiating for peace, the Six Day War ended forever Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s pan-Arabic vision of a united Arab Middle East, with Israel gone. Oren questions whether Israel’s victories in the current war will similarly end the Iranian vision of pan-Islamism. He notes that even Iran has begun deemphasizing its status as an Islamic state in favor of Iranian nationalism.

Whatever happens, he writes, the pre–October 7 status quo has been “irreparably shaken,” and the “regional aftershocks will be felt for years.”

One of the first of those aftershocks may have been hinted to in a letter addressed by five sheikhs in the Hebron district to Israel’s Economic Minister Nir Barkat, in early July. In that letter organized by Wadee al-Jaabari, the sheikhs recognize Israel as the nation-state of the Jewish people. In return, they seek recognition for the Hebron district as a separate emirate and request to enter the Abraham Accords on that basis.

Jaabari told the Wall Street Journal that “there will never be an independent Palestinian state — not even in a thousand years.” Certainly not after October 7. The only thing the Oslo Accords have brought, he continues, are “death, economic disaster, and destruction.”

Admittedly, little more has been heard of the sheikhs’ letter since it was first reported in the Wall Street Journal in early July, and the entire initiative has been dismissed as “unrealistic” by a number of Israeli academic experts on Arab clans. Nevertheless, the willingness of Jaabari to publicize his letter and to meet with Israeli minister Barkat over a period of five months may signal a change in attitude at least among some Palestinians.

As Adi Schwartz and Einat Wilf conclusively demonstrate in their The War of Return, the Palestinian movement led by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem totally rejected the existence of any Jewish sovereign entity in the Land prior to the creation of the State of Israel, and has continued to refuse to recognize the permanence of Israel as a Jewish state until today by insisting on the so-called “right of return” for millions of refugees from 1948 and their descendants. Though both Schwartz, who wrote for Ha’aretz, and Wilf, a former left-wing MK, are supporters of a two-state solution, they argue that no such solution is possible until the Palestinians abandon their dream of a Middle East without Israel.

That has thus far proven impossible for the Palestinians and much of the larger Arab world to do for two reasons — one theological and the other sociological. In Islamic theology, there is a concept of dar al Islam, land under Islamic sovereignty. Once land attains that status, it is considered an affront to Al-lah for Islamic sovereignty to be replaced by any other.

In addition, traditional Arab society is an honor-based society. The defeat of much larger Arab armies by Israel in 1948 was an affront to Arab honor that had to be erased. And Israel’s continued ability to defeat its Arab enemies, not to mention Israel’s comparative economic prosperity over its Arab neighbors, remains a continued stain on Arab honor.

One of the positive aspects of the letter of the Hebron sheikhs, beyond their recognition of Israel’s continued existence amid its Arab neighbors, is their focus on the prospects of a greater economic prosperity and a better life for their clans through building ties to Israel. In other words, a better life in the here and now appears to trump theological considerations.

These clan leaders no doubt remember that between 1967 and 1993, when Israel controlled Judea and Samaria, the area boasted the fourth-fastest growing economy in the world. The letter’s reference to the Abraham Accords is significant for the same reason, as those accords have largely been promoted in terms of the economic opportunities that they open up for the signatories.

Jaabari makes clear that he has his eyes firmly on economic development. He proposes in the initial stage of the agreement that 1,000 workers from the Hebron area be admitted into Israel to work with a goal of eventually increasing that number to 50,000. In addition, he proposes that Israel establish an industrial zone in the Hebron district that would undoubtedly greatly expand opportunities for the district’s residents to gain high-level training and dramatically increase their economic prospects.

While the sheikhs’ letter at present represents only a glimmer of hope, at some point it may come to be seen as the beginning of the end of more than one hundred years of Arab rejection of Jewish sovereignty in any part of the Land.

ALMOST FROM THE BEGINNING of Israel’s military actions in Gaza, Prime Minister Netanyahu has been hounded with the question — What comes after Hamas? — a question obviously impossible to answer without knowing the circumstances of Hamas’s defeat. Yet the Biden administration kept trying to use October 7 to bootstrap into reality all past failed efforts to create a Palestinian state under the banner of the decrepit and widely despised Palestinian Authority.

Yet Mahmoud Abbas, now in the 20th year of his four-year term as head of the PA, has explicitly refused to renounce the claimed “right of return.” In addition, the PA continues with its “pay for slay” policy of supporting the families of terrorists who kill Israeli Jews. Both of these facts make it an unacceptable alternative to ruling Gaza in Netanyahu’s eyes.

Nor is it imaginable that any Arab peacekeeping force would prove better at preventing Hamas from rising again than UNIFIL observers were at preventing Hezbollah from rearming in southern Lebanon under UN Security Council Resolution 1706, which ended the 2006 Second Lebanon War. Or that such a force would remove the “jihad curriculum” from UNRWA schools in Gaza.

Last week, however, an armed Popular Forces militia in Gaza, under the leadership of Yasser Abu Shahab, publicly announced its opposition to Hamas and desire to protect a Hamas-free zone in eastern Rafah. Prime Minister Netanyahu admitted that Israel has provided the group with arms and charged it with guarding the distribution of humanitarian aid in the area from Hamas’s attempts to commandeer that aid and use it to enrich itself and maintain its control over the population.

Admittedly, it’s hard to view the Popular Forces militia as the harbinger of a bright, new day for Gaza, The degree of destruction in Gaza means that much of it will be uninhabitable for years to come, even after rebuilding efforts commence. Yet remarkably, no Arab country has agreed to receive residents of Gaza, despite their professed concern for the well-being of Gazan civilians. Multiple surveys show that a majority of residents would be eager to leave if there were some place to go.

And it may well be that many members of Abu Shahab’s clan have been involved in criminal activities, including smuggling to and from Sinai, under the Philadelphi Corridor. But the great advantage of the clan from an Israeli point of view is that it does not share Hamas’s jihadist fanaticism. All agree that a thirst for jihad drove Yahya Sinwar.

True, Hamas’s leadership, including Sinwar, whose wife was filmed moving through an underground tunnel with a $30,000 Hermes Birkin handbag, has not been adverse to siphoning off large sums of foreign aid. The senior Hamas officials in Qatar, headed by the late Ismail Haniyeh, are estimated to have amassed personal fortunes totaling $11 billion. But jihadism remained their principal motivation.

Not so Abu Shahab, who claimed in a Wall Street Journal op-ed that the group could bring as many as 600,000 Gazans, about one-third the population, under its protection.

NOT ALL THE CHANGES growing out of the current war relate to shifts in Palestinian attitudes. Israel has also drawn important lessons from the nearly two years of fighting. One of those is that it must undertake production of its own munitions so as not to face the same situation as it did when the United States under President Joe Biden cut off or slowed down delivery of crucially needed munitions.

And the war speeded development of weapons systems already in the pipeline — most importantly, the Iron Beam laser aerial defense system. Drones have become one of the mainstays of modern warfare, and they are great equalizers. Case in point: the June 2 Ukrainian attack on Russian air bases from the border with Finland in the west to Siberia in the east, over 4,000 kilometers from the frontlines of the war. Ukraine employed 117 drones, many of them smuggled deep into Russian territory and then launched remotely, to destroy on the tarmac Russian bombers designed to carry cruise missiles. Ukraine claimed to have knocked out one-third of the bombers in question and caused $7 billion in damage to Russia, while exposing the vulnerability of Russia far from the frontlines.

Sophisticated drones can be manufactured for a few thousand dollars, but the interceptors used to shoot them down cost $35,000 to $40,000 and can be overwhelmed by a massive drone attack. Nor are the interceptors in infinite supply.

That is what makes Israel’s mobile Iron Beam laser air defense system — now battle-tested — such an important development. Lasers cost next to nothing to fire, and do not have to be reloaded after every firing. And they never run out of ammunition.

“Once the system is built, the variable cost of shooting down a drone or other projectiles is merely the cost of electricity, and you can’t run out of interceptors after a swarm attack by drones,” says the head of the IDF’s laser system division.

As a consequence, the addition of laser beams to the tools available to shoot down drones, rockets, and missiles, as part of a multitiered air defense system, is a game changer.

THERE WAS PLENTY of negative news about Jews and Israel still left to discuss this week. But with the end of the Three Weeks, I decided to give it a break.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1073. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.