Client: Bonei Olam

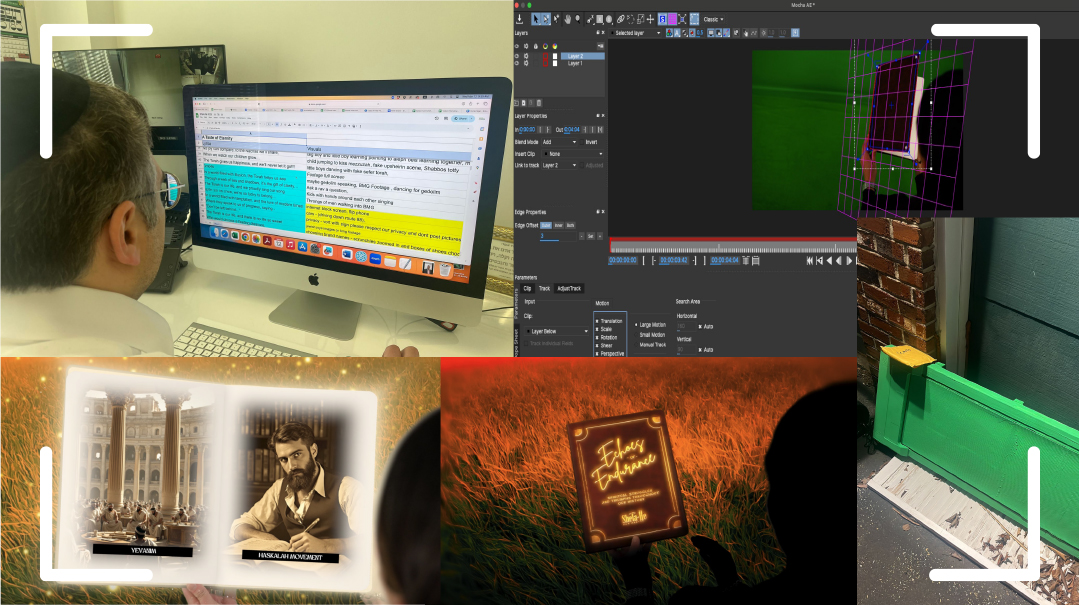

| July 29, 2025Outtakes from a Video Production Studio

Client: Bonei Olam

Objective: Create a full-length feature for Tishah B’Av

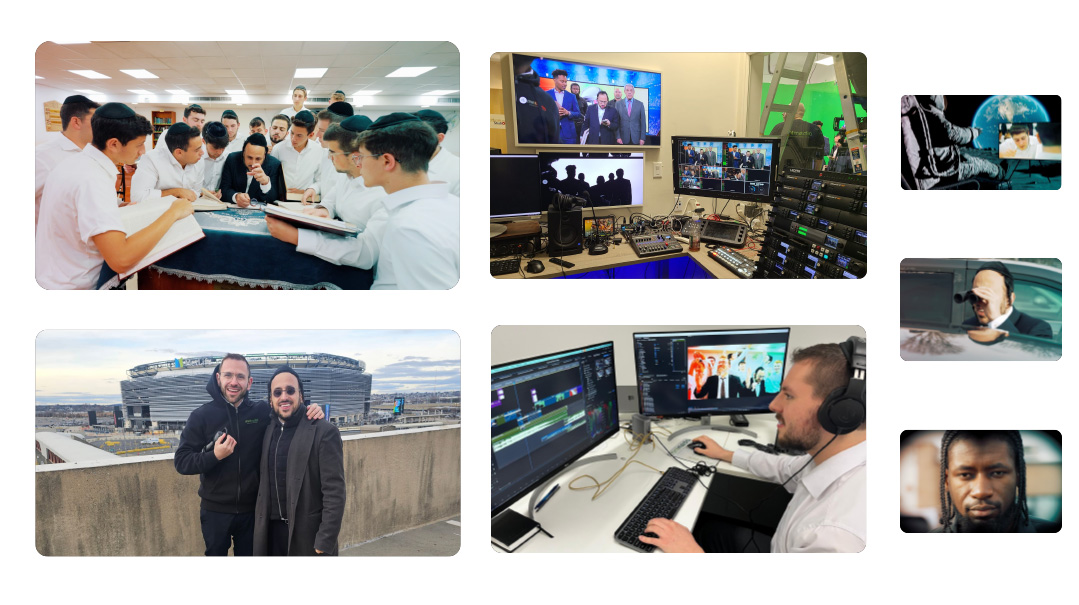

Film locations: Vilnius, Lithuania; Beit Shemesh, Israel; Boro Park, New York

Project Deadline: Tishah B’Av 5785

The Proposal

Tishah B’Av is a day of profound mourning for Klal Yisrael — a time to reflect on the Churban, the galus, and the many tzaros we’ve endured — yet truly connecting to the day can be challenging. In recent years, video has emerged as a powerful medium to help people tap into the day’s latent emotions in a real way.

This winter, Boruch Goldberger, Bonei Olam’s chief marketing officer, reached out with a meaningful idea. He shared that Rabbi Shlomo Bochner, the organization’s cofounder, had long dreamed of visiting the kevarim of tzaddikim who were never zocheh to have children.

“Rabbi Bochner believes that these tzaddikim, having personally experienced that pain, could serve as potent meilitzei yosher for couples today struggling with infertility,” he explained.

Boruch asked if we would join Rabbi Bochner on this journey — documenting the visits, capturing his heartfelt reflections, and giving voice to the silent suffering borne by so many. The vision was to create a film to be released on our nation’s day of mourning, a fitting moment to highlight the quiet, constant suffering of those yearning to build a family.

Oops! We could not locate your form.