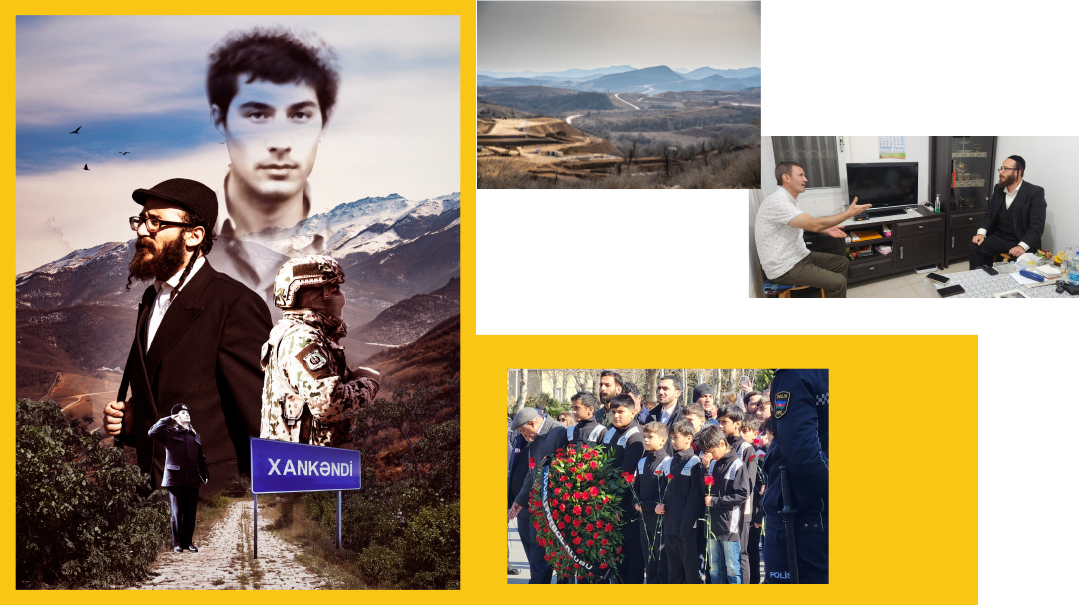

The Missing Jewish Son of Karabakh

| April 8, 2025A daring trek through no-man’s-land to find a Jewish soldier gone missing

Photos: Jake Turx, Branden Eastwood, Serxan Medetli

They never heard from him again.

Three decades have passed since Vugar Mikhailov bid goodbye to his family and went to join his unit on the front.

Two wars and three decades later, his family still hasn’t given up hope

By Jake Turx, Azerbaijan

HE left his family’s doorstep on a crisp winter morning in 1993, a quiet, Jewish 19-year-old boy from the Azerbaijani town of Goychay. His mother begged him to stay. His brother offered to buy him a plane ticket out. The draft board had turned him away. But Vugar Mikhailov refused to listen.

“My country needs me,” he told them. And with a small bag slung over his shoulder, he disappeared down the dirt road, off to rejoin his unit fighting in Karabakh’s frozen hills.

What followed wasn’t death. It wasn’t life either. It was something far more unbearable:

Nothing.

No word.

No grave.

Just whispers — sightings, secondhand rumors, a scattered trail that faded as quickly as it appeared. A witness who claimed to have seen him in captivity. A rumor he was forced into slave labor. A file, a photo, silence.

For more than thirty years, his family has waited in limbo.

Hoping.

Wondering.

In 2023, with the battle lines redrawn and the dust of war barely settled, I returned to the hills and hollowed villages where Vugar’s trail went cold. As I pushed further into Karabakh — the minefields, the rubble, the ghost towns still smoldering from war — I’d discover that harder than losing someone is not knowing if they’re lost at all.

CHAPTER ONE

Where Time Stands Still

Kiryat Bialik, Israel: August 23, 2023

I meet the Mikhailov family in Vugar’s mother’s modest home in Kiryat Bialik, a quiet suburb near Akko, in August 2023. Vugar’s mother sits on the couch, dressed in a patterned black-and-white housedress and colorful headscarf, her hands resting gently in her lap, her eyes betraying years of tears. The rest of the family stands or sits quietly against the side wall.

A simple gray couch is pressed against one white plastered wall; a pair of wedding photos hangs on another. On the lace-covered table, alongside a tray of fruit and water bottles, I notice a pack of disinfectant wipes and a bottle of hand sanitizer — relics of Covid. And between the fruit bowl and scattered remote controls, a small, square-framed black-and-white photo catches my eye. It’s Vugar.

I look at this boy, frozen in time, decades younger than the grief that now filled the room. His gaze is steady, almost shy; suddenly the weight of the years, wars and borders separating us from him feels even heavier.

“How did you hear about my son after all these years?” Vugar’s mother asks, her voice a mix of curiosity, gratitude, and tentative hope. She speaks a blend of Russian and Azerbaijani, while Ilgar, Vugar’s tall and wiry older brother, who is fluent in Hebrew, tries to bridge the conversation between his mother’s Azerbaijani — a language he speaks well — and my English — a language he doesn’t. Conversations flow like a multilingual chess match — Russian to Hebrew to Azerbaijani to English and back again, leaving the poor translators — Vugar’s brother-in-law with the assistance of his wife — dizzy. But despite the linguistic hurdles, there’s no mistaking the emotions threading through the room.

Vugar Mikhailov was born on January 4, 1974. His parents, Avraham and Nina, lived in the city of Goychay, a quiet town in Soviet Azerbaijan known for its pomegranate orchards and mix of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian communities. From a young age, Vugar worked hard, spoke little, and observed much. “He was always so quiet,” his mother tells me wistfully, her fingers fiddling with the edge of her sleeve. “But his eyes… they missed nothing.” He had a knack for needlecraft and tailoring, and a fascination with motors and tractors. “He was a good tailor,” she adds, her voice caught between pride and pain.

Quite anomalous among Soviet republics, Azerbaijan wasn’t particularly aggressive in stamping out religious observance. Jewish traditions quietly endured, passed from one generation to the next. “There was no synagogue in our village,” Mrs. Mikhailov recalls, “but there was a rabbi. In fact, my grandfather, Rav Elyatar, was a big rabbi in Baku. We celebrated the holidays, kept the traditions. Even during the Soviet years, the government never made any problems.”

Vugar grew up with a firm awareness of both his Jewish and Azerbaijani identities, and the family gently debates over which Jewish holiday was his favorite. His sister suggests Shavuos. His mother immediately recalls Rosh Hashanah. But his older brother, Ilgar, smiles and settles the matter. “No, no — it was Pesach. I remember how much he loved matzah.” He mimics Vugar munching on the dry cracker, and for a fleeting moment, laughter lightens the room.

They describe how Vugar would spend hours standing by the main road, waiting for elderly villagers struggling under heavy loads, just so he could lend a hand. “That’s who he was,” his mother says simply.

When the First Karabakh War broke out in 1992 — with Azerbaijan engaged in a raging conflict against Armenia, a few Russian battalions, and an assortment of mercenary groups — that kindness manifested as fierce loyalty to his country. For 18-year-old Vugar, the odds didn’t matter. His country was at war. His people needed him. “He wasn’t on the draft list,” his sister says. “He was young, and they told him to go back to his family.” But Vugar refused. “Many people fled — to Ukraine, Russia — but he chose to stay,” his brother-in-law adds. “He wouldn’t let others carry the burden alone.”

His determination paid off, and at the end of 1992, he donned his uniform and left home. Three months later, in January 1993, Vugar was granted a five-day leave to return home for his birthday. His sister remembers his quiet pride. “A real man belongs on the battlefield right now, not at home,” he said.

When not with family or friends, he “spent time with the elderly villagers, checking if anyone needed anything,” his mother remembers, smiling through the weight in her eyes.

She pleaded with him to stay home. “The government already decided who has to go,” she entreated. “You weren’t called up. Why must you go?”

She pauses before continuing, voice cracking slightly. “ ‘My country needs me now,’ he said. ‘Not joining is like running away. It’s not fair for some to risk their lives and others not.’ ”

Ilgar, who was married and living in Kazakhstan at the time, offered to fly him out. “I told him I’d book him the next flight to Kazakhstan,” Ilgar recalls. “He refused.”

Before returning to his base, Vugar took his passport and national ID card. His mother questioned him. He reassured her: “Don’t worry. I need it. The army might send me to Baku for officer training.” She saw a glimmer of opportunity and tried once more. “I gave him the passport and told him, ‘Take this. Go to Kazakhstan.’ He smiled, said, ‘No thank you,’ and left.”

That was the last time they saw him.

Later, the Mikhailovs received a visitor. In Azerbaijan of the 1990s, there was no army official with a white-coated nurse to carefully deliver the dreaded news; it was the father of a comrade of Vugar’s who knocked on their door and told them that Vugar had been taken prisoner. He had gone to visit his son, he told them, who asked him to pass through Goychay on his way home and tell the Mikhailovs what had happened to their son.

In one heart-stopping moment, eerily reminiscent of the nightmare so many families are living today, the Mikhailovs were swept into the vortex of a whirlwind of desperate longing and uncertainty.

Desperate for more information, they turned to the army, but didn’t learn much. They knew he’d been taken prisoner — “his commanding officer swore to us he was captured alive,” says Nina — and that his journey into captivity started in the Fuzuli district, near the village of Shekher.

The scanty answers offered little comfort. In desperation, Ilgar and his mother visited a Jewish mystic living in Ganja. “He looked at Vugar’s photo, read from a scroll, and peered into a glass of water,” Ilgar recounts. “Before we even explained the situation, he said, ‘He’s been taken captive.’ Then he added, ‘Don’t bother searching, don’t waste money — you won’t succeed. Many years will pass and he’ll come back through the intervention of a third country.’ ”

When the war ended in 1994, nearly all non-Armenians were expelled from Karabakh (a region of Azerbaijan with a sizable Armenian population), leaving behind a population consisting of 99.7 percent ethnic Armenians. Separatist militias seized control of the few mountainous roads leading into the region and proclaimed the creation of the Republic of Artsakh. With no international recognition, the self-declared republic had no formal diplomatic channels to the outside world. Though prisoner exchanges between Armenia and Azerbaijan did occur, Vugar’s name was conspicuously absent from every list. The family was at a loss.

Over the years, they clung to fragments of testimony from people claiming to have seen Vugar in various towns in Karabakh. One classmate managed to escape captivity and claimed to have seen Vugar in Chartaz, a small village tucked away in the mountains not far from Xankendi, Karabakh’s capital. He described captives forced to work as slaves, assigned to Armenian families. But contact with that classmate was lost long ago. Another witness claimed to have seen him in a prison in Shusha. The last known sighting claims he was seen in Xankendi in 2001. Since then, the trail has run cold.

Still, Vugar’s mother hasn’t lost hope. “He is alive,” she declares. “I’m certain. I can feel it.”

Though the rest of their family had long since resettled in Israel, Vugar’s parents remained in Azerbaijan for years, unwilling to leave without him. By 1999, however, they made aliyah as well. “Living there without my family became too difficult,” Nina admits.

In 2000, Vugar’s father, Avraham Mikhailov, met with Robert Kocharyan, the president of Armenia, during an official visit to Israel, and had the opportunity to present Vugar’s case. “My father gave him all the information and the president promised to look into it,” Ilgar says. “But we never heard back.”

Recently, the family sent an associate to Armenia. “He checked every list,” Ilgar says. “Vugar’s name wasn’t on any of them — not as a captive, not as deceased.”

“Maybe pressure from Israel or the United States could help,” his sister suggests. “Israel’s relationship with Azerbaijan is strong. Maybe that could finally get us answers.”

Avraham, Vugar’s father, was hospitalized at the Carmel Medical Center in Haifa in 2006 for an eye infection, but it was grief that seemed to consume him. “He stopped eating. He wouldn’t leave the house. Vugar’s disappearance ate away at him.” Within ten days his broken soul broke away from his broken body.

The decades that have passed haven’t extinguished the family’s hope. “Maybe he married and settled down in some village in Karabakh,” Ilgar muses. “Or maybe Georgia, even Iran. Anything is possible.”

Could Vugar have simply started a new life in the rebel-occupied areas, closed off to the outside world without means of contact? The family wonders. Or perhaps he’s alive, but lost his memory?

Every whispered theory, every far-flung possibility, keeps circling back to the same haunting question: Could he still be out there?

It’s a question they’ve been asking for more than thirty years. Now it was my turn to start asking, too.

CHAPTER TWO

A Fuse Is Lit in Fuzuli

Baku, Azerbaijan, February 22, 2023

The first time I hear the name Vugar Mikhailov is at a chance encounter in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, where I’d been spending time gathering information and capturing footage for a documentary I was putting together. In meetings with Azerbaijani government officials, they speak at length about the lingering aftermath of the wars — the challenges of clearing over a million land mines, and the grim process of locating and unearthing mass graves scattered across the region and identifying the remains.

It’s at a meeting with representatives from the State Commission on Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing Persons bureau, tasked with accounting for the thousands who vanished during the conflict, that I see a familiar face — Rabbi Zamir Isayev, currently the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Azerbaijan — whom I’d first met in Azerbaijan back in 2017 and more recently in Washington, D.C. As the discussion wraps up, I overhear Rabbi Zamir leaning in to quietly ask if the bureau had any updates about two missing individuals: Asad Hamidov and Vugar Mikhailov — two Jewish soldiers who vanished during the First Karabakh War — one in Khojaly and the other in Fuzuli.

The officials respond in the negative, and I scribble the names in my little notepad, not yet realizing how pivotal this conversation will prove to be.

A few days later, I’m with Rabbi Zamir, who’s working on the documentary with me; and Branden, my cameraman; driving to the newly liberated city of Shusha, previously held by Armenian separatists. As we drive past the desolate remnants of Fuzuli — flattened villages, gutted homes, endless ruin — I realize why the name rings a bell. “Hey, Fuzuli!” I exclaim, gesturing out the window. “Isn’t this the place where that Jewish boy was taken prisoner?”

Rabbi Zamir nods, and I feel a fuse lit beneath me.

For the next three days, I quietly reach out to officials, piecing together whatever fragments I can about Vugar and the circumstances of his disappearance. It soon becomes clear that we’re already close enough to investigate — close enough to try.

So we circle back to Fuzuli, specifically to Seyidahamadli Village, about a 50-minute drive from the spot where Vugar was reportedly captured. I’m following a lead from the State Commission for Hostages and Missing Persons that prisoners from that area were brought in to Seyidahamadli, then under Armenian control, to be processed before eventually being transferred deeper into enemy lines. If they made it out of the processing center at all, that is.

The processing center itself no longer exists — it’s been obliterated, like so much else in Karabakh after decades of war. But what caught the attention of ANAMA, Azerbaijan’s national demining agency, was what lay behind the ruins: a yard densely packed with land mines. That detail raised unsettling possibilities. Why mine a site so heavily unless there was something, or someone — or someones — they were trying to keep hidden beneath the surface?

Branden and I spend the day with a 17-member demining crew split into two separate groups, watching and documenting as they meticulously sweep the ground for hidden dangers. From a safe distance, sipping tea under a pale sun, we watch them defuse several mines — each small click and thud a reminder of the buried hazards.

While it isn’t practical to launch an investigation into Asad Hamidov’s case, since Khojaly is still under separatist control and the information we have about him is so sparse, Vugar’s trail, while scanty, feels within reach.

What’s begun as a trip to commemorate victims and document the rebirth of Shusha turns, almost imperceptibly, into something else: the search for one missing Jewish son of Karabakh.

CHAPTER THREE

Ghost Town

February 26, 2023: Partly Liberated Territory of Karabakh, Azerbaijan

There’s no welcome sign at the entrance to Karabakh, a mountainous region in middle of Azerbaijan, which until recently had been in the hands of Armenian separatists. Instead, there’s a trench, its concrete edges, once hastily fortified, now sagging under years of neglect. An old Armenian helmet, half-buried in the sand, peeks out of the mound like a grim relic from a forgotten battlefield. Scattered atop the trench walls empty tin cans dangle eerily.

This was once the front line of a conflict that lasted nearly three decades, dividing territories, families, lives. Behind me is Azerbaijan proper. Ahead, the vast, scarred expanse of Karabakh, freshly liberated but far from free.

Fuzuli is the first town on the Azerbaijani side of the Karabakh border. Or at least, it used to be a town. Today, it’s an open-air graveyard of buildings. Their skeletons are scattered across the hills like broken teeth — walls hollowed out, roofs collapsed, rebar twisting skyward. Destruction stretches as far as the eye can see. Entire neighborhoods have been flattened to the ground, their outlines barely discernible under layers of dust and silence.

These ruins are what remain after two wars — the First Karabakh War, which erupted in the early 1990s, and the Second Karabakh War, fought almost 30 years later in 2020. The first war left tens of thousands dead, over a million displaced, and the entire Karabakh region and a few surrounding districts — including Fuzuli — under Armenian control. The second, brief but fierce, saw Azerbaijan reclaim large swaths of territory, including Fuzuli itself, in a decisive military campaign that lasted 44 days.

“Since 1992,” Aykhan Hajizada, spokesman for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs told me in the early days of my search, “as a result of the aggression against Azerbaijan, not only were 30,000 Azerbaijanis killed, around another 3,800 are classified as a ‘missing person.’ This fact was established by the ICRC as well, and we have all the names of these missing people. We knew that most of them were in Armenian captivity and that Armenia had never provided information about them. This is one of the major topics in our normalization efforts with Armenia.”

Hajizada also tells me about the mass graves that have been discovered since the liberation, and that efforts are underway to identify victims via DNA testing. I check in with the Commission for Hostages and Missing Persons and ask if they have a sample of Vugar’s DNA. They do. Months later, I get a call from Gazanfar Ahmadov, the commission’s secretary, who tells me four new suspected mass graves have been discovered near the Xankendi area and that if they find a DNA match with Vugar they’ll let me know.

While there was no positive match, it feels reassuring to know that I’m not the only one who hasn’t given up.

On my first visit, in February 2023, much of Karabakh — including the regional capital Xankendi — is still in the hands of separatist Armenian forces, which has branded itself as the illegitimate “Republic of Artsakh” — unanimously unrecognized, even by Armenia. A fragile ceasefire clutches an uneasy peace in place.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan lay claim to Karabakh, a mountainous enclave the size of the combined states of Maryland and Delaware, nestled within Azerbaijan’s internationally recognized borders but home to a large ethnic Armenian population. As the Soviet Union crumbled, old nationalist tensions flared. Karabakh became the spark. What followed was years of bitter fighting, displacement, and destruction, punctuated by brief lulls before hostilities flared anew.

Ironically, Karabakh itself is beautiful. Snowcapped mountains loom in the distance, framing the kind of landscape that begs to be lived in, painted, sung about.

But down here, on the ground, there’s only wind whistling through weeds and empty homes. Sometimes, the wind carries a faint rustle; the sound of a lone plastic bag fluttering its way across a minefield, like a scrap of history left behind, tattered and weightless.

You don’t need to search far to see the danger still lurking. Just a few feet beyond the trenches and crumbled facades lies a seemingly empty field, littered with debris. A red warning sign punctures the landscape — “Danger Mines” — its skull and crossbones emphasizing that every step here is potentially one’s last.

Dotting the minefield are tombstones, in various stages of destruction and desecration. Some cracked down the middle, others tilted or shattered by artillery shells. Yet, at the base of quite a few gravestones, you notice something startling — neatly laid flowers, bright against the bleak earth, a quiet testament to family and friends who have ventured here despite the risk.

The border itself is a razor’s edge, slicing Fuzuli right through its middle. On one side: trenches, minefields, and endless destruction. The separatists never rebuilt the towns and villages on their side of the Fuzuli District. But drive just a single kilometer into the Azerbaijani-controlled part of town, and suddenly, life resumes; shops open, schools functioning, traffic humming. Crossing from one side to the other feels like stepping between parallel worlds.

A little deeper into the rebel-held territory lies Seyidahamadli Village, where captives from this region, quite likely including Vugar Mikhailov, were once processed. The village today bears no markers of its grim history. Just more rubble, another forgotten name on the map. But as we drive past it, something lingers in the air. It’s the kind of place where silence presses heavier than sound, as if the past is still pacing, just out of sight. It’s a place where time has stopped, where humanity pressed pause and never quite resumed.

As I stand at the edge of Seyidahamadli Village, staring at the hollowed-out shell of what once might have been a processing center, it feels like staring into an abyss, one where answers remain buried beneath layers of earth, rubble and silence. Somewhere in this no-man’s-land of abandoned trenches, collapsed homes, and empty fields, Vugar’s trail had gone cold.

Or did it?

Because on September 19, 2023, just three weeks after I first met with Vugar’s family, fighting erupts in Karabakh once again. The 3,000 Russian peacekeepers stationed there promptly pack up and check out. In a matter of hours, Azerbaijan reclaims the rest of Karabakh, finally bringing the territory back under full control for the first time since Vugar’s disappearance.

But even as borders shift, one burning question remains: What happened to Vugar?

I have little more than fragments to go on, but I’m determined to trace his steps. I don’t know what I’ll find, but I’m determined to try, to bring some hope or closure to the sad-eyed woman sitting in her living room near a black-and-white photo of her son, still waiting, for so many years.

CHAPTER FOUR

Mine Over Matter

February 29, 2023: Liberated Fuzuli District, Karabakh, Azerbaijan

The drive to Aşağı Seyidahamadli Village, one of the many towns in the Fuzuli district to be wiped out by war, is a bumpy, crater-riddled ride. Dirt roads, pockmarked with potholes from past shelling, snake between the barren, abandoned fields. Our vehicle rocks violently from side to side as we crawl deeper into the traumatized terrain. Every jolt is a reminder: this isn’t just a remote village — it’s one of the most perilous stretches of land on earth. Beneath the ground — and sometimes above it — lie remnants of violence. Mines, tripwires, unexploded ordnance. This is no place to let your guard down.

It would have been terrifying, if we weren’t doing this trip in the company of 17 professional, highly trained deminers from ANAMA, Azerbaijan’s National Agency for Mine Action. Their calm focus stands in stark contrast to the invisible threats lurking beneath the surface.

The area ahead had already been cordoned off. Red-tipped stakes and rocks painted a garish crimson form a narrow lane of safety. Some still bear wet streaks of paint from that morning’s preparation. This is life and death, drawn out in straight lines and red splotches.

By now, I’m accustomed to the odd juxtaposition that defines postwar Karabakh. A gentle breeze carries the scent of dust and dry grass. Wisps of clouds float lazily above. Birds chirp freely, yet beneath every step lies uncertainty.

We pause near the remains of a house — just a crumbling wall with faded red letters spelling out “Seyidahmadli.” It’s one of many skeletal structures left to decay, the former occupants long gone. For the deminers, this scene is typical. For me, it feels frozen in time, eerily quiet but filled with tension.

The team’s leader, Rovshan Gozalov, a deminer with 22 years of experience, walks us through the day’s plan, gesturing at a map pinned to a makeshift easel, his fingers tracing out plots marked in red. This isn’t just a routine sweep; it’s part of a wider, systematic operation. For the next few months, they would be zeroing in on a particular stretch of land, 6,880 square meters to be precise, that they suspect might conceal something darker: a mass grave.

Each miner wears a heavy vest, helmet, and visor, their movements deliberate and measured. Some sweep metal detectors rhythmically over the ground. Others crouch or even lie prone, digging carefully with small trowels, inch by inch, peeling away layers of earth in search of death traps set decades ago. It’s painstaking work. The terrain is unrelenting — trenches, barbed wire, rusted cans hanging like ominous ornaments — but the team pushes forward.

Alongside them, specially trained dogs sniff along perimeters, together with giant African pouched rats, specifically trained to sniff out explosives. “We’re always looking for new, innovative solutions,” says Samir Poladov, deputy chairman of the board at ANAMA. “A rat’s nose has much stronger sniffing abilities than the dog, and is more effective — nothing like the street rats you may be used to. The downside with rats is they’re smaller and they cover less ground than the dogs.”

I’m allowed to hold one briefly. (They’re unexpectedly heavy and for a piece of banana they’ll become your best friend.)

Land mines aren’t the only problem the ANAMA team is facing.

“The Soviet army had a big military presence here and they had large storage facilities,” Mr. Poladov explains. “In 1991, when they withdrew from the country and Azerbaijan gained independence… they didn’t want to leave this ammunition for us, so they just blew them up. The problem is, when you blow up such a large ammunition warehouse, only ten or 15 percent actually detonates and the rest gets scattered around.”

Adding to the surrealism is the simple kitchen area set up in the middle of the danger zone — a battered kettle perched over a few rocks and an open flame, a few blue canisters filled with water, and a crude table where the men brew Azerbaijani black tea. We join them at a plastic table, sipping from glass cups, the surreal juxtaposition sinking in.

“How often do accidents happen in your line of work?” I ask Mr. Gozalov, the team leader, between sips. “More journalists have been killed by mines than professional deminers,” he answers helpfully. I cough.

He tells me about two Azerbaijani journalists who were killed when their vehicle triggered a land mine, underscoring this grim reality. While deminers operate with specialized training and equipment, journalists, guided by their pursuit of stories, frequently traverse these hazardous terrains with limited protective measures rendering them vulnerable. Thankfully for us, we have Mr. Gozalov and his team at our side.

The air feels calm, almost too calm, as if the land itself is holding its breath. Suddenly, off at a distance, a pair of prearranged explosions rip through the air, shooting two plumes of smoke a kilometer up in the air. I take another sip of tea. This day had just gotten even more interesting.

After a half hour lunch is over, and we go back to our respective jobs. As the deminers meticulously scour the terrain, a moment of levity breaks the tension. One of the miners, noticing our cameras trained on their operations, takes a brief respite. With a grin, he pulls out his mobile phone and begins recording us recording them — a lighthearted inversion that draws chuckles from both sides. In this landscape of latent danger, such human connections serve as poignant reminders of resilience and shared experience.

I also reach out to the State Commission for Hostages and Missing Persons, tasked with tracking down suspected mass graves and doing requisite forensic investigations and testing to the remains.

“Before 2020,” says Ali Maharrav, representing the head of the commission, “when we liberated the lands, the only effective thing the commission could do was to gather the information. So we set up a huge database for all the victims. We have files where all the documents are gathered from each and every missing person. But we couldn’t do anything on the ground. We didn’t have any access.

“Since 2020, after we regained the territories, we started excavations. In the first year, we’ve uncovered the remains of 36 individuals.”

The demining operations press on for months, and I remain in close contact with the team throughout, receiving updates and photographs.

On May 17, 2023, Araz Imanov, a senior advisor to the President of Azerbaijan who was closely involved in the search for the mass grave, sends me a five-letter text. “Empty.”

The exhaustive search had come to an end. They’d cleared vast swaths of land, but there was nary a mass grave in sight. The coordinates and intelligence that had guided the mission had led to naught but empty earth. The initial hope of uncovering a mass grave that could provide closure to families like Vugar’s is met with the stark reality of the land’s silence.

I reach out to Vugar’s family, and let them know, choosing to frame the developments with a positive spin. “The chances that he’s still alive have just gone up,” I say.

For the families of the missing, each cleared field holds the potential for answers, yet often yields only more questions. By this point Vugar is starting to feel like family. And like Vugar’s family, I also feel at a loss.

A few months later, Azerbaijan’s unexpected sweeping liberation of the remaining Karabakh territories will open a whole new set of doors. The problem now becomes where to even begin.

CHAPTER FIVE

Charting Chartaz

June 2, 2024: Chartaz, Karabakh

Our convoy slices through the heart of Karabakh, the freshly reclaimed terrain still raw, the scars of war barely beginning to scab over. I’m on my second visit to the region, hoping to progress on my quest now that Azerbaijan has fully reclaimed the territory from the separatist control.

We have four days to cover three cities, Chartaz, Shusha, and Xankendi, and only fragments of a thirty-year-old trail to follow. Joining me is Rabbi Zamir, who has temporarily set aside his educational duties at the frum school in Baku (under the auspices of Vaad L’Hatzolas Nidchei Yisroel and the Department of Education in Azerbaijan) to partake in this mission, and two special forces agents.

I had invited Ilgar, Vugar’s older brother, to join us on the search. Perhaps treading the same ground his younger brother had last been seen would trigger some helpful detail stored deep within his mind after all these years. Regrettably, he wasn’t able to find a replacement at work and so he was unable to join us. But we made sure to keep him apprised of our progress all throughout, and he in turn reported back to his mother.

Once outside the Baku city limits, we move fast. Too fast. Once, twice, thrice, we are pulled over by law enforcement officials, and a few times we’re halted by military vehicles. Each time, the special forces agents smooth things over, and ultimately we shave two hours off the five-hour drive.

As we journey toward Chartaz, the landscape transforms into a series of hauntingly abandoned villages, each bearing silent testimony to the region’s turbulent past. The winding roads connecting these villages, once bustling with the footsteps of daily life, are now overgrown with weeds and flanked by encroaching vegetation. Gray, shriveled pomegranates still cling to their branches, untended and neglected.

The electricity is long dead, water shut off, the silence thick as concrete. The eerie stillness evokes a deep sense of melancholy. Even the stray dogs slink by quietly as though their voices, too, have been gone for decades. The journey through these desolate landscapes, marked by dilapidated homes and deserted highways, evokes a post-apocalyptic tableau.

Nestled at the foothills of jagged cliffs, overlooking a gentle stream, stands one final checkpoint — the most picturesque of them all. Just beyond a quaint little bridge, a security booth and a modest shack mark the outpost, the shack doubling as the guards’ living quarters. The expressions on their faces hover somewhere between intrigued and inconvenienced, as though our arrival has disrupted an otherwise uneventful day. I wonder how often their quiet was disturbed by passing vehicles.

“Rarely,” they admit.

“When’s the last time you’ve seen a Westerner come through?” I ask.

One guard smirks. “Including you?” he says. “Only you.”

They take our documents, made a few phone calls, returned them, and wave us on.

Once inside the liberated zone of Karabakh, it quickly becomes clear that while people are few and far between, their presence lingers unmistakably. In one abandoned warehouse, we find a Soviet-era truck (because the separatist-controlled area was cut off from the world, most of the technology was from the 1990s or earlier), its doors hanging ajar, the exterior cloaked in dust. Inside, civilian clothing and scattered signs of recent habitation suggest it has served as a makeshift refuge. “Could that have been Vugar on the run?” I ask aloud. The rest of the team exchanges sincere shrugs.

I shoot off a message to Ilgar: “We’re now entering Chartaz.”

“Safe travels, I’m sure you’ll succeed,” he says. “With Hashem’s help you’ll succeed. Only with Hashem’s help, I’m confident.”

Ilgar is certainly sounding more and more religious as time goes by, I observe.

Further up the road, we stumble upon a derelict gas station, now overtaken by nature. In a cramped little room — what must have once passed for a convenience store (though by location alone, I’d call it an inconvenience store) — hundreds of empty glass bottles litter the floor, alongside a single, soiled mattress. “Could this have once housed Vugar?” I wonder again.

As we ventured deeper into the Karabakh countryside, we encounter unexpected remnants of the recent conflicts. Nearly every town in Karabakh bears two names: the Azerbaijani name recognized by the government, and the Armenian name imposed during the decades of separatist control. Often, these names are so dissimilar they seem to reference entirely different places. (Xankendi, for instance, was called Stepanakert by the separatists, Khojaly was changed to Ivanyan, while Fuzuli became Varanda.) While the Azerbaijani names have since been restored, traces of the previous nomenclature still linger in certain areas.

One such example emerges during our approach to Chartaz. The village is so far off the grid that we aren’t entirely sure whether it is called Chartaz or Chartar. One soldier in a military vehicle identifies it as “Chartar,” and when we arrive, we find a rusted sign at the town’s entrance reading “Chartar,” a vestige from the separatist era left in place simply because this stretch hadn’t yet been updated.

Since the sign was written in Armenian, I conclude the correct Azerbaijani pronunciation would be Chartaz. (It turns out, as I’d later discover, both versions are acceptable in Azerbaijan, along with Guney-Chartar and Charpaz. I decided to stick with Chartaz because that’s the name Vugar’s family uses.)

Chartaz is frozen in time. An entire town of about a few hundred houses seems to have paused mid-breath. Has Vugar been here? I was going to brave the war-torn territory to try and find out.

ANAMA had cleared the main thoroughfare and select side streets; the remainder of the city remains untouched. They assign to me a personal booby trap diffusing team, led by Eyvaz, who catches up with us inside Chartaz, with a demining truck outfitted with enough equipment to clear a war zone. They even set aside a protective suit and gear in my size.

Eyvaz speaks about as much English as I speak Azerbaijani, so we mostly communicate through gestures, gesticulations, and awkward chuckles. Over the course of our investigation, we meticulously examine 19 homes and a number of establishments. Eyvaz checks each doorway before I enter, eyes sharp for tripwires, booby traps, or any cruel surprises left behind.

The interiors tell stories of abrupt departure; the 2020 and 2023 Azerbaijani takeover saw the separatist Armenians departing in droves. Dining tables remain set, meals unfinished. Suitcases are half-packed, unfinished children’s art projects and school assignments are scattered on the floor, clothing lies strewn across rooms, and toolboxes sit abandoned mid-task. Pantries are stocked with vibrantly colored pickled vegetables, and commercial establishments still hold Soviet-era currency in their registers, accompanied by handwritten receipts.

One of our most poignant discoveries is an uneven stone road ascending a gentle incline, flanked by overgrown vegetation. The weathered stones, interspersed with resilient grasses, hint at a haunting permanence. Intelligence information indicates that such infrastructure was often the result of forced labor, possibly involving captives. I think of Vugar, and the gravity of our mission weighs more heavily.

My emotions swing between empathy for the families forced to abandon their lives here, and a deep, gnawing disgust at the thought that they may have stood by, watching my brother Vugar — shackled, humiliated — forced into backbreaking slave labor.

“This place feels much heavier than I imagined,” Rabbi Zamir whispers to me emotionally.

While hunting for signs of life, I also try to imagine the life of a prisoner. What kind of room would he have been kept in? What kind of lock? What kind of hiding place might remain if, by some miracle, Vugar has survived all this time, concealed amid this quiet decay?

I assume that if slaves had been kept here, they wouldn’t have shared a bunk bed with an overseer’s seven-year-old kid. No, slaves would’ve had their own secure sleeping quarters. And since the townsfolk clearly didn’t wait around once making the decision to flee, it’s unlikely that they had the time to dismantle any slave-holding infrastructure.

The one-room shacks tucked behind houses with padlocks on the outside catch my interest. Also, markedly telling are empty cellars we chance upon, covered with some sort of trapdoor, accessible via narrow staircases, leading to confined spaces measuring approximately eight by four feet. These areas, sufficient for two individuals to sleep, seem plausible as makeshift detention quarters, but suspicious as it appears, this isn’t a determination I can conclusively make.

The town feels like a museum of the abandoned. A living exhibit curated by absence. Every object left behind feels like a question.

Our search extends to drawers and closets, each of which requires Eyvaz’s expertise. Official-looking documents are brought to the attention of the appropriate authorities in the hopes that some of them may contain helpful data. We document all anomalies while taking pains to leave everything as intact as we had encountered it. I entertain, and quickly dismiss, the thought of tracking down and questioning former residents with the help of passports and documents that were left behind. Those are now the property of the Azerbaijani Foreign Ministry and besides, my workload is oversaturated as is.

Despite the picturesque surroundings, an undercurrent of unease persists. The weather fluctuates between breezy sunshine and cold rain, mirroring the emotional oscillations of our quest. I grapple with the limitations of a single day’s search, yet remain committed to our mission to find Vugar. Embracing the principle of hishtadlus, we diligently conduct our search until darkness starts to creep in. Since spending a night in abandoned Chartaz isn’t on our to-do list, we make our way toward Shusha.

CHAPTER SIX

Paper Graveyard

June 3, 2024: Shusha, Cultural Capital of Karabakh

Shusha is where poetry meets the past.

The cultural capital of Karabakh, once a cradle of poets, composers, artists and mystics, had over the years become a target, a prize. During the Second Karabakh War, neighboring Russia — Armenia’s ally — was called in to mediate a ceasefire. As both sides prepared for drawn-out negotiations, the Russians made one thing clear: Under no circumstances was Shusha — then still in separatist Armenian hands — to be touched. But Azerbaijan’s elite commandos had other ideas. Scaling cliffs nearly a kilometer high, they bypassed the only road into town, then under separatist control, and descended upon the city from behind, catching the occupying forces completely off guard. Shusha fell, and the war changed course.

While it became the first major city in the region to undergo redevelopment, most of Shusha still bears the trauma of battle. By now, I can tell which buildings have been destroyed in the first war and which have been blown apart more recently. Some structures have collapsed inward; others are hollowed-out shells, with jagged shadows replacing windows and silence echoing louder than artillery.

One structure in particular called to me. Not as a journalist, but as a brother.

The Shusha prison.

If there was any chance Vugar had passed through this city, that fortress-like prison on the edge of the mountain would have been his likely destination. The family told me one witness had claimed to have seen him there years ago. We make it our first stop.

From a distance, the prison looks oddly majestic, perched high above the valley, encircled by thick outer walls, and overlooking a panoramic vista more suited to a luxury spa than a place of punishment. “At least you can’t complain about the views,” I comment wryly. Inside, however, it’s exactly what you’d expect.

We enter cautiously. The courtyard is littered with broken furniture and debris, and the exterior walls are pockmarked with bullet holes and shell damage. Parts of the roof have collapsed. Glass crunches beneath our footwear. The corridors are dark and drafty, with long iron bars casting striped shadows across walls, once whitewashed, but now blackened with grime.

Standing in the cellar, I try to picture Vugar. Did he pace here, back and forth, wondering if anyone was looking for him? Did he think he was forgotten?

Moving up to the prison’s upper floor, formerly the administrative offices, we find chaos.

Papers. So many papers. Tens of thousands of them. Scattered across every surface, ankle-deep in the hallways, cascading out of file cabinets like a bureaucratic avalanche. The furniture has been rearranged into makeshift barricades. Heavy desks, chairs, cabinets all pushed together in haphazard defense. The separatists had clearly used this floor as a final holdout during the war.

I immediately spy the index cards.

They’re prisoner files. Each one contains basic details — names, birth dates, cell assignments, along with a black-and-white, thumbnail-sized mugshot. Though the writing is almost entirely in Armenian and Russian, the dates are recognizable. The oldest prisoner listed had been born in 1947; the youngest in 1997.

My breath quickens. If Vugar’s name is here, it would serve as the first concrete piece of evidence contradicting Armenia’s longstanding claim of having no record of him. Until now, officials have consistently denied knowledge of his whereabouts. But a single prisoner card — misfiled, overlooked, or simply forgotten — could change everything.

We set up shop.

I tape a photo of Vugar to the wall, next to the Armenian and Russian spellings of his name, then gather the team: Rabbi Zamir, the two special agents, and our cameraman. We devise a system. All the scattered documents are swept into the main hallway, and each of us takes up a position and begins sorting. Anything that isn’t a prisoner file is tossed back into the nearest room, while the prisoner files go into an overturned metal cabinet we’d repurposed for organizational purposes.

The work is grueling, sifting through files that whisper about lives no one remembers. Not the “building a stone road with bare hands,” kind of grueling, I keep reminding myself.

There are no lights in the building and the only natural light comes from cracks in the walls and ceiling. We take turns holding up our phones like torches, our flashlights barely illuminating the aged ink. By 3 p.m. the sun has already dipped behind the mountains, extinguishing the last rays filtering in. Still, we press on.

As we work, the prison takes on an eerie familiarity. Something about the cracked white corridors reminds me of elementary school. Maybe it’s the quiet. Maybe it’s the repetition. Maybe it’s just the smell of old paper and dust. I wonder what Vugar must have felt like, entering these very corridors for the very first time.

Four hours in, my back aches and my eyes are blurry, but my mind remains sharp. I feel I have the stamina to stay indefinitely. And I would have, too, if not for the dying lights on our phones and the total darkness closing in.

At one point four Azerbaijani soldiers appear, curious about the commotion on the upper floors. I explain our mission to one soldier with decent English, and he relays the story to the others. Within moments, they join our search.

I tell them Vugar’s date of birth, January 04, 1974, and urge them to pay extra attention to those digits before placing cards in the file cabinet.

For 15 surreal minutes, uniformed men work shoulder-to-shoulder with us on the floor, sorting prisoner files under the dim glow of a camera light. Then, after receiving a few heartfelt çoxsağols and thank yous, they’re gone.

Despite locating and combing through nearly 300 prisoner files, we find no trace of Vugar.

That doesn’t mean he wasn’t here. It only means the record may still be buried or misplaced.

I brush myself off from the dust accumulated from among the thousands of pieces of paper. On one of them, I imagine, a 19-year-old boy looks sadly out. Still young. Still waiting. I wonder how many times he chastised himself for not listening to his mother and staying home. How many times did he play out their long-awaited reunion in his head? Did he believe he’d see his mother again as sincerely as she believes it?

As of now, that entire trove of documents remains in the upper floor of the prison, caught between the dust of time and the machinery of bureaucracy. There are apartments to build. Cities to reconstruct. Displaced people to house. The fate of ghosts is low on the list.

Before leaving the prison, I shoot a few quick instructional videos for the benefit of an acquaintance in Baku, who has agreed to put together a team that would go through the documents in my absence.

That evening, back in Shusha, I message Ilgar. No breakthrough yet, I tell him, but we haven’t given up. He sends back a simple line: “We’re praying. We believe you’ll find something.”

Meanwhile, we still have one last lead — a witness the family had heard from decades earlier but with whom they’d long lost contact — a secret document cache stored in the vaults below the Xankendi police station.

CHAPTER SEVEN

An Ex-City

June 3, 2024: Xankendi, Under Military Administration

I can’t say I ever imagined that I’d one day visit a city that starts with the letter X. Yet here I am, approaching the sign welcoming us to Xankendi, a name that — like the city itself —is still adjusting to its post-conflict identity.

Our first attempt to enter fails. It’s late in the day, and as a military town, there’s a curfew in place that’s rapidly approaching. When access is denied, we double back to the Kharibulbul Hotel in Shusha, resolving to try again the next morning.

The drive from Shusha down into the valley is both stunning and unsettling. Spring has scattered pink, yellow, blue, and purple wildflowers across the slopes, little bursts of color blooming endlessly. But the mood briefly takes a turn for the ominous when we pass some of the crumbling monuments left behind, silent witness to the bygone brutalism of the Soviet era.

This time, we get through the checkpoint without issue.

We see immediately that the city is different. Wide boulevards. Vibrant floral displays. Modern apartments. Upscale neighborhoods. Malls with gleaming facades. Compared to the other cities we’ve visited, the damage here is cosmetic: a few shattered windows, broken signage and neglected storefronts. (As the separatists agreed to give over the city peacefully to the advancing Azerbaijani forces, it was spared the carnage we’ve seen elsewhere.).

But something is off. The city is bizarrely empty. I hear short bursts of metropolitan noise from time to time, and then they dissipate, echo and all. There are people, yes. Engineers, contractors, a few hundred soldiers, sure. But no residents. No families. Hardly any life. And at the center of it all are two Orthodox Jews, one rabbi and one journalist, strolling in the middle of the main road of a deserted thoroughfare.

Our first lead is already gone long before we get here. After spending a nice chunk of time driving around the same deserted streets and making a number of phone calls, we learn that the jail where Vugar was allegedly once held has been demolished years ago. The old police headquarters has also been replaced by a sleeker and more modern facility; while I imagine this is much appreciated by its occupants, it’s of no help to us.

We meet with the region’s governor general inside. He is cordial, even accommodating. Sure, we can search the vaults. But no, this isn’t the same facility and besides, his vaults are empty. And the documents? Gone. When the self-declared Republic of Artsakh collapsed, its officials allegedly smuggled sensitive records into Armenia proper. With such a head start they could be just about anywhere, or nowhere.

He patiently repeats the same line five or six times, each time trying a different phrasing. But I am not satisfied. How can he be sure they’re all gone? Did anyone actually see them being taken? Had anyone asked the Russians, who had maintained a presence in the city until recently? What was Armenia’s official position on the missing documents?

Eventually, realizing I wasn’t making headway, I make a different kind of request. A personal one.

“Could I visit Tatik-Papik?” I ask, electing to go with the monument’s Armenian name because it’s snappier than the more widely accepted “We Are Our Mountains.”

“No,” he says apologetically. The monument, and the hill it sits upon, is a restricted zone, off-limits. He can’t say yes even if he wanted to.

“Have you ever made an exception?” I ask.

“Let me see what I can do,” he responds after mulling it over.

So we wait. Meanwhile, I decide to check out the city’s first functioning grocery store further down the street. I’m looking for a souvenir for my friend Ambassador Elchin Amirbayov, a senior government official, who’d been posted in Xankendi in 1991 and hasn’t been back since. Something symbolic, ideally local.

Through a translator, I ask the grocer for a nice bottle of vodka. The man laughs.

“This is a military town,” he says. “No alcohol around here.”

No success there, but just then the call comes in, and I wind up with something better — permission.

My request had moved all the way to the very top of the chain, and they’d managed to arrange a special exemption. I have an appointment with Tatik-Papik.

Perched atop a hill, the Tatik-Papik or “Grandmother and Grandfather” monument has kept silent watch over Xankendi since 1967. Chiseled from red limestone, their stoic, stony faces seem to rise directly from the earth, weathered by time, but unmoved by it.

Originally sculpted when the entire region was part of the Soviet Union, the monument, the best-maintained one of that era, was meant to evoke the permanence of identity in a region perpetually in flux. (Since this monument was built by Communists there were no concerns it had ever been used for avodah zarah.)

Standing in the silence, looking at a land scarred from so much war, I find myself wanting to pray. And so I do. For Vugar. For his mother. For the hundreds of my other brothers and sisters taken hostage by the cruelest of captors, those who’ve come home, those whose return came too late, and those still held in those dark tunnels; for the thousands of lives cut short; for the millions of teardrops already shed.

The words of Yeshayahu (25:8) echo in my mind:

“U’machah Hashem Elokim dimah me’al kol panim — And Hashem, your G-d, will wipe away the tears from all faces.”

I cry for what I’ve seen, for what I’ve imagined, and for what I still hope to find. Then I turn toward Yerushalayim, and with the faces of stone behind me, I daven Minchah.

We begin our exit from Xankendi as the sun dips low behind the mountains. Cell reception had been spotty throughout the day; once we’d hit the first set of mountains our portable satellite unit came screeching to a halt. Now, as we reenter civilization, my phone finally rings. It’s my father.

“I’ve been trying to reach you,” he says. “I was thinking… when your travels bring you to places where a Yid hasn’t stepped foot in many years — perhaps ever — it’s a special moment. Say a brachah. Daven. Even something small in such a place can accomplish something great.”

He has no idea where I’d been.

But of course, he does. That’s my father.

No Closer to Closure, But Not Closed Either

There’s a particular kind of fatigue that settles in after months of chasing fleeting fragments, decaying documents, muddled memories, wayward witnesses, tangled traces, footprints faded by time, and clues gone cold. Not the kind of fatigue that wears down the body, but the kind that weighs on the mind. The kind that sets in when you’ve come so close to something without even so much as sniffing it.

The search for Vugar Mikhailov began with a single question: What happened to him? And it quickly evolved into something much larger. His case isn’t an isolated one; it’s emblematic of so many others, names still whispered in uncertainty by those who loved them.

What became clear throughout this journey is that for the families left behind, the need for answers doesn’t fade with time. It sharpens. If Vugar is no longer alive, then his family deserves to know. They deserve the right to mourn with certainty. And if he is alive, then every day that passes is one more day spent waiting. Hoping. Wondering.

Though we’ve covered ground — outposts, villages, archives, dungeons, institutions, abodes — we’ve only scratched the surface. Leads have narrowed, but not disappeared. The trail has cooled, but has not ended. There are still documents out there, people who may speak, records that may resurface. There’s DNA testing underway. And there’s a growing hope that the postwar landscape, now under full Azerbaijani control, may bring the access and transparency that’s been denied for the last thirty years. Perhaps, even, cooperation from those who had remained silent for decades.

This story has taken me through war-torn cities and across newly rebuilt roads. I’ve seen devastation and rebirth, often just blocks apart.

Construction has already begun in hundreds of towns and villages across the region. These are the new “green cities,” where cutting-edge architecture rises alongside thoughtful, artistic monuments. Though the pain of loss can never be undone, thousands of families displaced since the 1990s are finally beginning to return. And in each of these towns, one small square of destruction is being deliberately preserved — so future generations will remember what happened here, and understand where their story began.

Even as life returns to Karabakh, my journey isn’t over. Not yet. Not while there’s still one name unaccounted for. Not as long as questions remain unanswered, not as long as there is a chance — however slim — that Vugar, or his truth, can be found. This has never been about the odds. It’s about the obligation. The responsibility to look. The commitment to not turn away just because the trail has gone quiet.

And so we keep going. Because silence is not the same as closure.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1057)

Oops! We could not locate your form.