Not Just Kever Hopping

Each generation finds a different pathway — so what if ours takes a detour through the graveyard?

PHOTO:SHUTTERSTOCK/ PRASZKIEWICZ

The Czarist forgers who wrote the Protocols of the Elders of Zion were wrong about many things. For one thing, we control the media in about the same way that we control the weather — namely, not at all. Forget global confabs of Jewish moneymen — Davos’s World Economic Forum is headed by a Catholic. And while our elders are indeed elderly, their identities are only shadowy if you don’t read the Yated.

One thing the anti-Semites got right, though: We do love graveyards. Whether Prague or anywhere else, kevarim exert a magnetic pull on us. How else to explain the fact that airports from Moldova to Morocco are choked with Jews heading to an endless stream of yahrtzeits and hilullas?

Every few years, it seems, another tzaddik is put on the pilgrimage map. Take Kerestir, for example. While the Tzaddik of Kerestir was very well known during his lifetime, twenty years ago, who beyond a few insiders had heard of Reb Shaya’le?

The trend — growing for decades — is increasingly color-blind and non-sectarian. Sephardim now flood Europe, and Ashkenazim return the compliment in North Africa. (All wearing abnormal headgear. You must either wear a Russian fur hat, a flat cap like a British country squire on a foxhunt, or a baseball cap that clashes with your suit.)

The Jewish nation has long been divided into two distinct camps: eye rollers and enthusiasts. The skeptics question why people leave Eretz Yisrael to daven overseas when their tefillos are anyway rerouted through Yerushalayim. They query why a guitar is essential kit for visiting a kever. They tsk-tsk about how we’re turning into an Am Segulah.

But year by year, those mutterings grow quieter, lost in the sound of the ceaseless pilgrimage to tzaddikim both modern and ancient.

Your humble correspondent was once a fully paid-up member of the first camp. I had a sneaking suspicion that “kever hopping” (as I called it) was a cover for something more basic: an escape for people who needed a holiday, but couldn’t admit to that human failing.

Like many aspects of my cynical youth, that attitude is now firmly gone, its final vestiges lying somewhere in southern Poland.

A short trip through Krakow and Lizhensk last week was a chance to ponder what draws millions to travel to far-off places to daven at the gravesite of a tzaddik whose work they may not be expert in, but whose zechus they are sure of.

The bottom line is that Klal Yisrael knows what they’re doing, because on all levels, the experience can be a spiritual journey like no other.

Late at night, I found myself shivering in Krakow’s ancient beis olam with a random assortment of visitors who, like me, had paid the exorbitant fee to enter.

There can be few places in the world that contain such an extraordinary collection of geonim per square meter. Somewhere between the Rema and the Bach (whose yahrtzeit falls on 20 Adar, the day of my visit), I became aware of someone next to me who was walking around in absolute wonder.

By his outward appearance, the young man was what we might classify as a struggling member of the yeshivah system. And yet, there in the Krakow graveyard, he was deeply moved.

“What a tzaddik!” he exclaimed when reading the inscription on the headstone of Rav Yehoshua Charif, the 17th-century author of Maginei Shlomo. “So many seforim he wrote!” he said with reverence at the kever of the Tosfos Yom Tov.

I have no idea what that young man’s story really is, but he clearly underwent some form of penny dropping as he soaked in the power of those bygone Torah greats. Because the kever of a tzaddik isn’t just a stone slab — it’s the material evidence of a real life, suffused with a greatness that is tangible.

If you talk to enough people who flock to kevarim, you’ll find that the magnetic attraction to kivrei tzaddikim is something inexplicable, operating on the soul level.

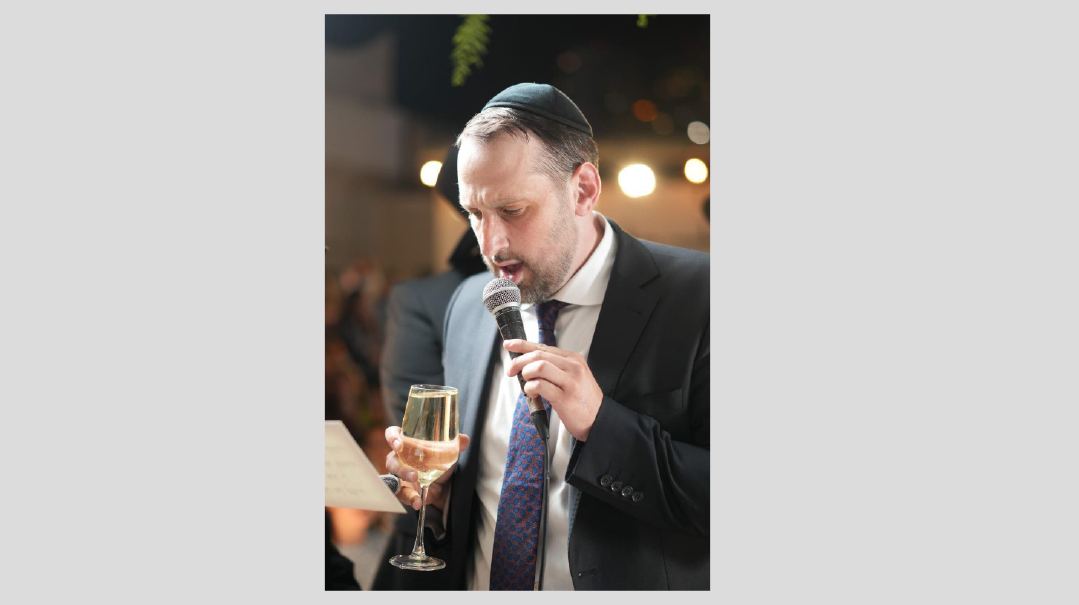

Deplaning in Krakow, I met someone who had an intriguing explanation for the phenomenon that we’re seeing. Rabbi Yonah Bookstein, a combination of thoughtful academic and kiruv innovator who lives in Los Angeles, has mileage in terms of Poland and kevarim.

Working in Poland for the Lauder Foundation in the late 90s, he was fascinated by the chassidim flooding into towns across the country. That led to a thesis at Oxford, and was part of his own spiritual journey that included yeshivah, semichah and an affinity with chassidus.

“The only way I can explain the sheer numbers journeying to kevarim is that the Jewish soul is programmed that in order to experience elevation, it must undergo a journey,” he says. “It’s something harking back to aliyah l’regel, when we had to make a journey to experience that uplift.”

Whatever the explanation, there’s no question for anyone who’s visited Lizhensk on the 21st of Adar, yahrtzeit of the Noam Elimelech, that some serious elevation is indeed taking place.

Both inside and outside the modest structure of the tziyun, the atmosphere was like Yom Kippur. People were sobbing, absolutely lost in tefillah.

It’s fair to say that about 99 percent of the people crying in a field in this little Polish town would not have had anything like comparable kavanah at home in Monsey or Manchester.

And therein lies the answer to the skeptics — those who rightly recall that our grandparents didn’t need to jet across the world to connect with Hashem.

The answer is that you can’t argue with facts. Somehow, in a world where we struggle so much for any spark of spirituality, countless people find it by the gravesides of long-gone tzaddikim. If once upon a time, that experience was reserved for chassidim, today the trickle of outsiders has become a torrent.

How does the Gemara put it? If the Jewish people aren’t neviim, they’re the sons of neviim.

Each generation finds a different pathway — so what if ours takes a detour through the graveyard?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1055)

Oops! We could not locate your form.