Tefillos for the Turkish Sultan

| February 11, 2025Jews enjoyed a level of prosperity under the relatively benign six centuries of Ottoman rule

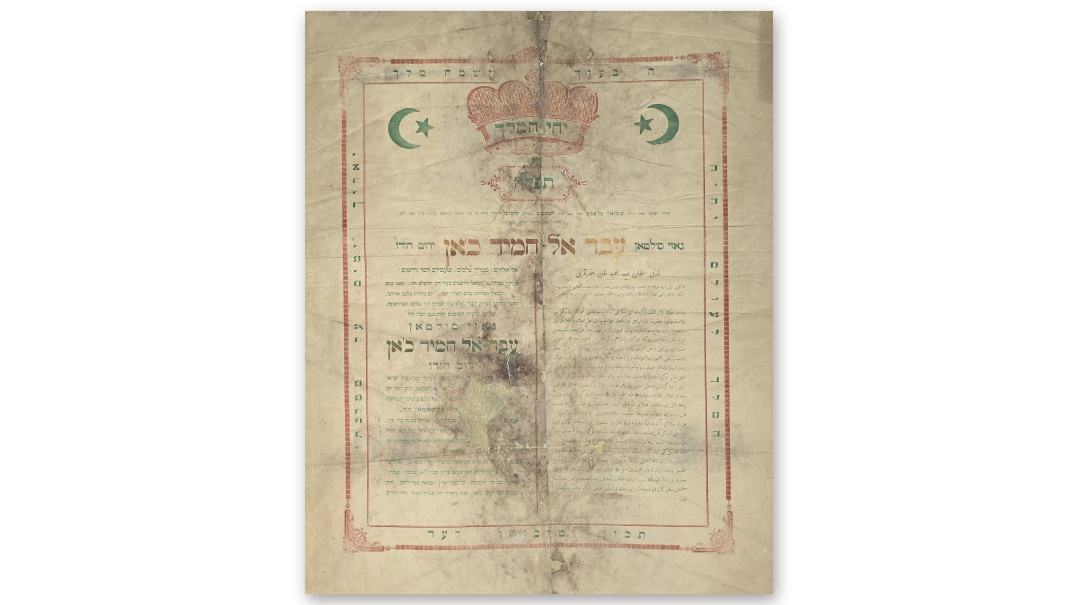

Title: Tefillos for the Turkish Sultan

Location: Jerusalem, ottoman empire

Document: Proclamation in honor of The Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid Khan

Time: Late 19th century

The Jewish community across the vast Ottoman Empire fared relatively well, especially compared to other-less fortunate Diaspora communities. Jews were relegated to “dhimmi” status, with various discriminatory laws limiting their participation in civil society and commerce, and they were required to pay the jizya, a high tax levied on non-Muslims in the empire. But they still enjoyed a level of prosperity under the relatively benign six centuries of Ottoman rule.

The Ottoman Empire saw a large influx of Spanish and Portuguese Jews following their expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula in the last decade of the 15th century. By the end of the 16th century, the Ottoman Jewish population was the largest in the world. The Ottoman government granted the Jewish community — as it did to other monotheistic minorities — a measure of legal and religious autonomy, with its own courts, under a recognized chacham bashi (chief rabbi).

By the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire was a backward, non-industrialized society facing economic decline and rising nationalism, known to the great European powers as “the sick man of Europe.” The sweeping tanzimat reforms of the 1840s and ’50s, which attempted to modernize the Ottoman economy and society, included the Imperial Reform Edict of 1856, granting equality and citizenship to subjects of all religions, and abolishing the hated jizya tax. An 1865 reform gave the Jewish community more autonomy in the form of a constitution and a Jewish national assembly.

With the rise of Sultan Abdul Hamid II to the throne in 1876, these reforms took a decidedly different turn. He continued to modernize the state bureaucracy, education, and industry, investing heavily in an expansion of the Ottoman railway system. But as a staunch Islamist and absolutist monarch, he slowed and even reversed some of the political and religious reforms of the previous decades. His rule, which lasted more than three decades, was the last to exert absolute authority in an increasingly fractured and weakened empire.

Meanwhile, the Yishuv in Eretz Yisrael experienced significant demographic growth, fed by immigration and natural growth in the Old Yishuv, and by the First and Second Aliyah, which gave rise to the New Yishuv. Eretz Yisrael had been under Ottoman rule since 1516, and many Jews in the Yishuv were Ottoman subjects. European Jews, however, generally maintained the citizenship of their countries of origin, and were nominally under the sovereignty of European rulers through their respective embassies in Jerusalem.

Despite this dual identity, the Jews of the Yishuv felt a strong loyalty to the Ottoman government and its rulers, and considered themselves Ottoman subjects. By the end of the 19th century, the European powers assumed the Ottoman Empire’s debt burden, effectively giving them control of the empire’s economy. Its military capabilities were crippled due to Abdul Hamid’s troubled relationship with the admirals of his navy, and his disastrous decision to ground the Ottoman fleet. If there was any time that the Ottoman sultan needed the prayers of his Jewish subjects, it was during this period.

Rav Shmuel Salant had first immigrated to Jerusalem from Lithuania in 1840, and served in various rabbinical positions in the Old Yishuv’s Prushim community for nearly 70 years. He headed the Prushim beis din, established the Eitz Chaim Yeshivah, oversaw the construction of the Churva shul, and had a hand in the founding of Bikur Cholim Hospital. His psak and advice were sought on every question facing the Yishuv.

One year, in honor of the sultan’s birthday, Rav Shmuel Salant issued a public proclamation in Hebrew and Ottoman Turkish (in Arabic script) calling on the Jewish community to pray for the sultan’s welfare. Such proclamations by communal authorities followed a long and honored tradition in Diaspora Jewish communities to pray for the welfare of the monarch and his government.

Rav Salant writes:

We, your Jewish subjects who reside in the Holy City of Yerushalayim, have come to pour out our hearts in prayer on this glorious day, the birthday of our great king, the righteous tzaddik, who is compassionate and modest, who is filled with might, power, glory, righteousness, kindness, and graciousness to all of his subjects who live under his kind protection, the great Sultan Abdul Hamid Khan, may his glory be exalted.

The proclamation goes on for several paragraphs in this vein. The Jewish community of Eretz Yisrael continued to express loyalty to the tottering Ottoman regime, but it didn’t help the sultan much. He was deposed in a coup in 1909, and died in Constantinople in 1918.

The Sultan’s Sephardic Chief Rabbi

Rav Yaakov Shaul Elyashar (1817–1906), born in the sacred city of Tzfas, rose to prominence as the Sephardic chief rabbi of Jerusalem from 1893 to 1904. A towering halachic authority and master diplomat, he navigated the delicate balance between Jewish autonomy and Ottoman rule. Following the passing of his father-in-law, Rav Rafael Meir Panigel, Sultan Abdul Hamid II personally confirmed his appointment, granting him an imperial firman and a robe of honor — a rare gesture of recognition.

Rav Elyashar worked tirelessly to secure communal rights, protect Jewish property, and advocate before Ottoman officials. A close confidant of Rav Shmuel Salant, he unified the Ashkenazic and Sephardic communities in a shared mission of strengthening Jerusalem’s spiritual core. When he died in 1906, both factions of the Yishuv mourned the loss of a leader who had embodied wisdom, dignity, and unwavering devotion to his people.

The Harsh Years of the Young Turks

In 1909, a group of Western-educated officers and intellectuals known as the Young Turks toppled Sultan Abdul Hamid II, determined to modernize the Ottoman Empire. Their vision of Turkish nationalism and centralization quickly clashed with the empire’s minorities, and quickly found a target in the Jews of Palestine. Foreign protections were stripped, Zionist land purchases restricted, and Jewish autonomy weakened.

Then came World War I. Jamal Pasha, the Ottoman ruler of Palestine, expelled Jews from Jaffa, imposed forced conscription, and cut off foreign aid, plunging the Yishuv into famine and desperation. Once-tolerated Jews were now seen as foreign agents, their survival hanging by a thread. By 1917, the British seized Jerusalem, and Ottoman rule in Palestine crumbled.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1049)

Oops! We could not locate your form.