Listen to the Language of Truth

| February 4, 2025While we’ve been learning Sfas Emes for 120 years, his personal life is still a mystery

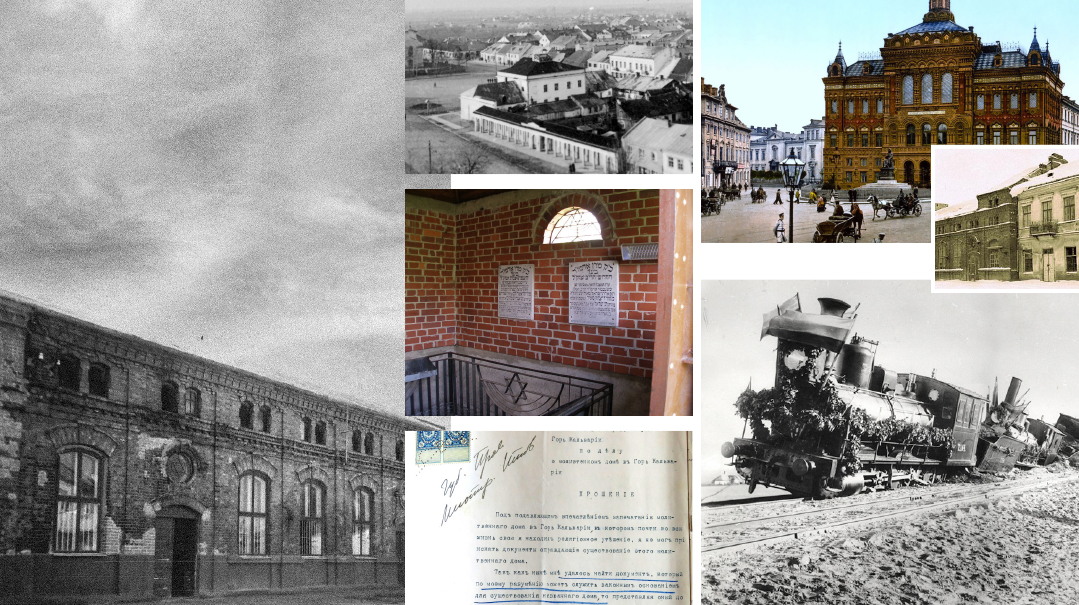

Photos: Machon Zichron Kehillos

While the Jewish world has been studying the works of the Sfas Emes for over a century, this second Rebbe of Gur is the only gadol of his stature about which no biography has yet been written, about whom we really know so little. Yet as we delved into a cache of old newspapers and notices 120 years after his passing, we got a glimpse into the Rebbe’s mesirus nefesh for his people living through frightening and threatening times

All over the Jewish world, rabbanim and lay people, scholars and balabatim, chassidim and Litvaks, continue to learn the holy works of the Sfas Emes, whose seforim — judging by the numerous editions and reprints — are among the most widely studied chassidic works in the Torah universe.

Yet even as Jews all over are marking 120 years since his passing on 5 Shevat, 1905, at age 57, most of them don’t really know much about his actual life. Many books have been written analyzing the teachings and philosophy of the Sfas Emes — Rav Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter, the second rebbe of Gur — yet in all these years, there has not been written a single comprehensive biography of his personal history.

Maybe that’s why, whenever a new personal detail is uncovered, it’s immediately pounced on — like a recently discovered clipping from a Jewish newspaper written by the wife of the Sfas Emes, a call for help regarding an unidentified 20-year-old deaf-mute girl who’d been found in Warsaw and placed in a Christian institution where she refused to eat the nonkosher food. The note was a plea to the community for her parents to come forward and secure her release — and at the bottom was signed, “Yocheved Alter, Rebbetzin of Gur.”

The dearth of information on the Sfas Emes is unusual for Polish tzaddikim — including the other rebbes of the Gerrer dynasty, all of whom has at least one biography written about them. The lone exception is the Sfas Emes. Why? Perhaps reverence prevented the chassidim from delving into his personal life; or maybe, the reason lies under the following anecdote:

The Sfas Emes was once walking through the courtyard of his beis medrash when he saw a group of chassidim gathered around an elderly chassid — Rav Bentzion of Ostrowa —listening attentively. The Rebbe continued on his way, but when he returned a short while later, he saw the same group still standing there, engrossed in conversation.

The Sfas Emes came up to the group and asked, “What are they discussing?” The chassidim replied that they were hearing stories and accounts about the previous Rebbe, the Chiddushei HaRim ztz”l.

The Sfas Emes responded with amazement: “Strange. I, too, spent time with my grandfather, the Chiddushei HaRim, and I don’t remember so many stories.”

The Rebbe paused for a moment and then added, in typical Kotzker fashion: “Perhaps it is because I absorbed the message rather than the stories.”

And there’s also a historical reason: Despite being a rebbe and the leader of the largest chassidic group in Poland, and despite the thousands — among them renowned rabbis of cities and towns — who flocked to be in his presence, the Sfas Emes himself hardly ever left his beis medrash. He remained secluded in his study, learning from morning until night, writing his vast Torah insights on Chumash and Talmud, dedicating his short life to illuminating the path for future generations — and the writings we have today are only a fraction of what he actually composed during his lifetime. In a certain sense, his wish to remain hidden was fulfilled.

Yet as we delved into a cache of old newspapers and notices we’d been given access to, we were able to uncover two pivotal campaigns for which the Sfas Emes worked tirelessly with every bit of strength he had — preventing secular studies in Talmud Torahs, and preventing Jewish young men from being conscripted into the Czar’s army.

IT

happened in the month of Elul of 5648/1888, as Polish Jewry prepared for the approaching High Holidays. Chassidim were already setting out on their journeys to their respective rebbes, but at the very same time, unbeknownst to the public, the rebbes of Poland also left their homes, as they made their way to the town of Grodzisk Mazowiecki, located on the main route to the capital city of Warsaw.

A secret gathering of the great tzaddikim of Poland was a highly unusual event — and especially during these days of intense spiritual preparation. What was the urgency? That year, Orthodox Jewry in Poland was facing a significant spiritual challenge, known in Yiddish as Shule-Tzvang (the decree of Compulsory Education).

The mastermind behind this reform was Czar Alexander III of the Romanov dynasty, who ruled the Russian Empire from 1881 until his untimely death in 1894 at age 49. He’s remembered in Russian history as “The Peacemaker” because he managed to keep Russia out of war during his reign. Domestically, however, he was far from lenient, and the Jews felt it keenly. After the relatively moderate and liberal (everything being relative in Czarist Russia) rule of his father, Alexander II, Alexander III flooded Russia, including Poland (which was under his control), with a nationalistic spirit. In his vision of Russification, all residents of Russia, Ukraine, and Poland would be a single nation, speaking one language, adhering to one religion (Eastern Orthodoxy), and governed under a unified administration.

This was no simple task, yet Alexander had no intention of relenting. During his relatively short reign, he worked to impose the Russian language on his German, Polish, and Scandinavian subjects (he married a Danish duchess). As always, the enforcement of this policy began with education. In the summer of 1888, the government mandated that all residents of Poland send their children to state schools where the language of instruction was Russian — which meant that all teachers were also required to be proficient in Russian.

It is easy to understand why this decree posed an existential threat to Orthodox Jewry in Poland. Who could possibly train G-d-fearing Polish melamdim to be fluent in Russian within just a few weeks? And beyond the practical difficulty, there was the even greater issue of compelling Jewish children to start speaking the language of the gentiles.

It was clear that a response was necessary. The secret assembly took place in Grodzisk for two reasons. One was geographical: this quiet town was centrally located in Poland, just 30 kilometers from the capital — close enough for easy access but far enough to avoid Warsaw’s many spies and informants.

The second and primary reason was the rebbe who lived there: the holy Rebbe Elimelech Shapira of Grodzisk, a talmid of Rebbe Yisrael of Ruzhin and considered the leading rebbe in Poland of his time.

The secret meeting was a who’s who of Polish tzaddikim: Among the attendees were the Avnei Nezer of Sochatchov, Rebbe Yechiel Dancyger of Aleksander, Rebbe Shimon of Skiernivitch, the Chesed L’Avraham of Radomsk, the Atarah L’Rosh Tzaddik of Porisov — and, at the request of Rebbe Elimelech of Grodzisk, the Sfas Emes of Gur.

The very existence of the gathering was kept secret, and according to reports, during the meeting itself, all escorts, attendants, aides, and even the sons of the rebbes remained outside the room. However, there was one exception: the young son of the Rebbe of Gur, who would later become known as the Imrei Emes. When everyone left the room, his father, the Sfas Emes, instructed him to stay. “He can keep a secret,” he told the others.

Still, the Russian intelligence services immediately sensed that something was happening, and a few detectives arrived in Grodzisk to investigate. They were told that the rabbi of Grodzisk was celebrating a birthday party and had invited all his colleagues.

We don’t have an authoritative record of what exactly was said in that room, but one thing we do know is that, at least from a public and historical perspective, this was the moment the Sfas Emes demonstrated his exceptional leadership skills. Despite being the youngest rebbe present (he was 41 at the time), he was honored to speak and, in effect, led the gathering. He began with a few words about how there were also Jews —adherents of the Haskalah — who rejoiced at the decree and were quick to comply, sending their sons to those schools, and that gave a certain spiritual power to the decree.

However, the Rebbe quickly moved on to practical matters. He said, “I have heard that the decree can be annulled if we manage to raise a sum of 300,000 rubles.” The Rebbe did not elaborate further and wasted no time dividing the sum among those present in the room: “I will take upon myself to collect 100,000 from my chassidim, the Rebbe of Grodzisk and the Rebbe of Aleksander will each arrange for 50,000, and the Rebbes of Sochatchov, Porisov, Radomsk, and Skiernivitch will each raise 25,000. This is how we will annul the decree.”

In Gur, where everything was measured in units of time, the chassidim noted that the gathering lasted exactly 15 minutes, down to the second. The Sfas Emes, who valued every moment precisely, wished to return to Gur, but the Rebbe of Grodzisk asked all the rebbes to stay for a short meal.

It was a remarkable gathering that was even hinted to in some chassidic seforim. (In the sefer Yismach Yisrael of Aleksander, for example, in the section on Shabbos Shuvah, the author mentions “a question I heard in Grodzisk in the name of the Holy Committee.” The Yismach Yisrael accompanied his father and was also present at the meal.) At that moment, the Rebbe of Grodzisk crowned the young Rebbe of Gur with the title “Melech Yisrael” and honored him with leading the zimun for bentshing.

The gathering, though, was not just about practical decisions. Among Polish chassidim, there was talk that a spiritual battle took place there against the forces of evil. (Besides the education decree, Alexander was hostile to Jews, and his reign witnessed a sharp deterioration in their economic, social, and political condition, with trade and business sanctions and renewed pogroms across parts of the empire.)

Of course, no one can verify the connection, but the historical fact is that a few weeks later, in October 1888, the train carrying the Czar and his family derailed about 50 kilometers from the city of Kharkov. Seven carriages overturned, and many members of the royal household were injured, although the imperial family miraculously survived — their carriage remained intact except for the roof, which was torn off. (The Jews of the nearby town established a synagogue to commemorate the miracle of the Czar’s survival.) However, despite escaping the accident, Alexander began to suffer from kidney pain, which ultimately led to his death six years later.

F

or the Jews, though, the trouble was not yet over. Two years later, in 1890, the tzaddikim of Poland once again convened a meeting to strategize, as the decree had resurfaced.

This time, the gathering took place in Warsaw. The Sfas Emes attended as well, accompanied by the Imrei Emes and two wealthy chassidim with government connections — Reb Yoel Wegmeister and Reb Shlomo Buchowitz. Two representatives of the progressive Jewish community were also invited: the famous physician Dr. Maximilian Herz, and his brother-in-law, the tycoon Israel Poznanski.

It was clear that they needed to find a “weak link” among the government decision-makers. During the meeting, the name of a Jewish apostate who was close to the royal court came up — Professor Daniel Khvolson from St. Petersburg.

Khvolson’s story was puzzling and mysterious. Despite converting to Christianity, he maintained contact with many great scholars of Lithuania and even used his connections to assist Jews. In fact, he studied in yeshivah until his was 18, when he decided to enroll in the University of Breslau, where he devoted himself to the study of Arabic and philosophy. On his return to Russia he settled in St. Petersburg, where, having embraced Christianity, he was appointed a professor of Oriental languages. Despite his newfound religious orientation, in his governmental capacity he defended Jews against rampant anti-Semitism and called out the imposters on several high-prolife blood libel cases.

When the Sfas Emes heard about Khvolson and his connections, he wanted to know how they could appeal to his heart. It turned out that Khvolson was a bibliophile, had a massive collection of Jewish books, and was an expert on the early history of Jewish printing. When the Rebbe heard this, he signaled to his son, the Imrei Emes, who was known as a rare book lover and whose personal library was one of the most famous in Poland. It’s recorded that before the delegation of activists from Poland traveled to St. Petersburg to enlist Khvolson’s support, they visited the home of the Imrei Emes and received a special gift intended to touch Khvolson’s soul: The Rebbe sent him eight volumes of the Talmud from the very first Bomberg printed edition.

One thing was clear: Khvolson and the delegation managed to buy silence. The compulsory education decree was not officially repealed, but the melamdim continued to teach as before, while the government officials turned a blind eye.

However, this still wasn’t the end of the story. A few years later, in 1903, the government once again attempted to reinstate the law, requiring the inclusion of government-approved content in Jewish educational curricula. Once again, the Sfas Emes understood that the ones behind this scheme were the “progressive” Jews. In a letter he wrote at the time, he lamented, “Regarding the additional matters that cause distress concerning the chadarim, I will tell you in person, G-d willing, when you come here. May Hashem annul the plans of the wicked, and may we hear only good news.”

Once again, the Sfas Emes convened a meeting in Warsaw. This time, the wealthy activist Reb Yoel Wegmeister was invited, along with another prominent benefactor, Reb David Tamkin. Also invited was Rav Moshe Nachum Yerushalmski, the rav of the town of Kletsk, a great scholar who was fluent in Russian and maintained correspondence with the authorities.

This meeting led to practical decisions. It was agreed that, in addition to lobbying the government, there should be an institutional separation between the children of chassidim and other religious Jews and the children of the “progressive” families, so that the desires of one group would not affect the other. While the progressive parents welcomed the decree, the Sfas Emes launched an all-out war against any sign of modernity for his chassidim.

An interesting excerpt from a Warsaw newspaper at the time lamented this situation, representing the perspective of the maskilim. In a 1903 Hazman piece, one journalist wrote:

The community leaders here (in Warsaw) follow the method of ‘Yachloku’ — that in the Talmud Torah, no secular subjects will be taught at all. The spirit of the Rebbe of Gur dominates the teachers…. Any compromise based on mutual concessions is completely impossible. The Rebbe of Gur has set out to save the Talmud Torah from the forces of impurity, at least partially, while leaving the rest in their hands. And his decree was fulfilled.

That same year, after the horrific pogrom that erupted in Kishinev, the capital of Bessarabia in the Russian empire, one of the regional rabbis traveled to the town of Gur and reported to the Sfas Emes that due to the violent attacks, there was no longer any financial support for the melamdim, and Jewish education was suffering. The Sfas Emes was deeply shaken by this news. Not only did he personally donate a significant sum of money, but he also commanded several of the wealthiest chassidic patrons to mobilize in support of Jewish education in Bessarabia.

T

he plight of cheder children was one huge responsibility on the Sfas Emes’s shoulders, but nothing compared to the complex challenge of conscription of Jewish young men into the Russian army.

In Russia itself, this was a terrible decree from which there was little room for escape. In Poland, however, which was a protectorate state, matters were somewhat easier. The Sfas Emes’s forerunners — including Rav Yitzchak of Vorka and the Chiddushei HaRim of Gur — led advocacy efforts that eventually resulted in an industry of exemptions and tacit agreements.

Still, there was no clear and established arrangement, and the danger loomed over every young man reaching draft age. Many young men starved themselves or even inflicted injuries on their own bodies to obtain an exemption.

For a young Jewish man to serve for years in the Czar’s army among non-Jews was practically a decree of Jewish self-destruction. The chances of maintaining one’s Jewish identity were slim — and that was aside from very real life-threatening dangers. Commanders in need of cannon fodder had no qualms about sending their soldiers directly into the line of fire.

This distress reached its peak in the final year of the Sfas Emes’s life, with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-1905, over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major battles of the war were fought in southern Manchuria, the Yellow Sea, and the Sea of Japan. To the distant front, precious young Jewish men — many of them Torah scholars — were sent. According to chassidic accounts, this decree drained the Rebbe’s strength, perhaps even having contributed to his sudden passing. During those days, he would fast frequently and dedicate long hours to finding solutions and offering support to those who came to seek his counsel.

Twice a year, during the conscription periods in the fall and spring, thousands of young men would crowd the Rebbe’s doorstep before heading to their military evaluations, and he would give each one individual guidance. At that time, a vast network of intermediaries and brokers developed, who would bribe military doctors and obtain short-term deferments. The Rebbe tried to assist each person in his own way.

Even on Leil HaSeder, when the Sfas Emes was usually strict about having only his family present, he opened his home to allow throngs of draft-eligible young men to be with him before their departure to the battlefield.

There are testimonies of how the Rebbe personally arranged hiding places for some young men facing the threat of conscription. Rav Mordechai David Weinstock of Jerusalem, son-in-law of Rebbe David Tzvi Shlomo of Lelov, testified that he arrived in Poland during those days and was shocked to learn that the authorities were even kidnapping tourists and sending them to the front. The Rebbe instructed him to hide in the basement of his home until the danger passed.

While there is little documentation of the Rebbe’s actions during those days, as everything was secretive and clandestine — a death sentence hanging over anyone who aided draft dodgers — some documents and testimonies have surfaced, revealing glimpses of the rescue efforts the Rebbe orchestrated.

For example, in the early stages of the war, in February 1904, General Martynov, the minister of the Warsaw district, issued an order that even young men who had previously received exemptions from military service must report again. As in previous cases, the Rebbe summoned activist Reb Yoel Wegmeister and urged him to intervene. At first, Wegmeister attempted to negotiate with the general, with whom he had connections, but that didn’t help. Wegmeister then managed to enlist a local businessman named Yatchevsky, who had ties with the military elite. Through an especially generous bribe, they were able to secure a reprieve for those in the Warsaw area with past exemptions.

However, thousands of other young men were still without exemptions, and the Sfas Emes continued his efforts on their behalf. One person the Rebbe connected with was a wealthy activist named Berish Shimkovitz, head of the Jewish community in the town of Kalisz. He was a distinguished member of the Gerrer kehillah in Kalisz, with strong connections in government circles and an expert on conscription issues. According to the town’s community records, he received a medal from the Czar and successfully secured exemptions for hundreds of young Jewish men from military service.

E

ven after all efforts, the long arm of the Russian Czar prevailed, and thousands of young men — even married scholars — were forced to go to the front. The Rebbe urged them to prepare for a double battle — both spiritual and physical. For instance, he advised one of his close disciples to memorize a tractate of Mishnayos before heading to the front. “Wherever you are, you will be able to review Mishnayos,” the Sfas Emes told him.

The Rebbe advised another young scholar to learn milah before his induction. The young man was surprised, but followed the Rebbe’s advice — and it saved him. It turned out that his unit had a Jewish officer who had a baby boy and needed a mohel. The bris earned him a discharge.

There is also a story of two young men who came to the Rebbe seeking advice on how to deal with their draft orders. To everyone’s surprise, the Rebbe looked at them and replied sternly, “How can you think of escaping? After all, the empire needs soldiers.” Only later was it revealed that those young men were undercover informants sent to check whether the Rebbe of Gur was arranging draft exemptions.

The farewell moments of devoted chassidim heading to the distant front were heart-wrenching. The Rebbe would shake their hands and briefly recite to them the verse spoken to those going out to war: “Who is the man that is fearful and fainthearted? Let him go and return to his house.” He would interpret it as: “Whoever is G-d-fearing should go and return in repentance, and then he is assured that he will return home from the war.”

But even after the painful farewells, the Rebbe could not get back to himself. Family members testified that during the entire period when all those young men were at the front, the Rebbe did not sleep in a bed. Instead, he lay on the floor, with only his garment spread beneath him. By morning, it would be soaked with his tears.

Letters from the front would arrive from time to time — from the bloody battlefields of Manchuria, young scholars would share deep analytical questions about various Talmudic topics, or would describe how they managed on Rosh Hashanah or on Succos in the trenches.

Yet at a certain point, the great heart of this leader could no longer bear the suffering of his flock. On 5 Shevat, 5665/1905, after a short and mysterious illness, Polish Jewry was orphaned of its beloved leader. But not really. Because even 120 years after his passing, his Torah is alive as ever.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1048)

Oops! We could not locate your form.