United We Stand for Yeshivos

| January 21, 2025How the spark of Torah learning persevered on American shores

Title: United We Stand for Yeshivos

Location: New York

Document: Der Tog

Time: 1943

This article is dedicated to Reb Yosef Rabinowitz and the devoted group of askanim who have made it their mission to sustain and nurture the lifeblood of Klal Yisrael—our yeshivos.

The success of yeshivah education in America is a testament to the determination and creativity of a community fighting to preserve its spiritual heritage in an unfamiliar and often challenging landscape.

In the early 20th century, waves of Jewish immigrants arrived on American shores, many bringing with them traditions of Torah study and faith deeply rooted in the Old World. However, the New World, with its pull toward secularization and assimilation, was not conducive to the rigor of traditional Jewish learning. Early Talmud Torahs and yeshivos were often poorly funded, operating in cramped quarters with limited resources. Yet thanks to a devoted few, the spark of Torah learning persevered on American shores.

The founding of Yeshivah Rabbi Jacob Joseph (RJJ) on the Lower East Side in 1903 marked a significant shift in Jewish education in America. After that, at least 23 Jewish day schools were founded in the New York metropolitan area alone during the period leading up to 1939.

In 1908, Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin opened its doors in Brooklyn, followed by Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem (1911) and Yeshivah Torah Vodaath (1919). In 1924, the Yeshivah of Crown Heights began serving the burgeoning Jewish population of Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn. By the late 1920s, institutions like Yeshivah Toras Chaim in East New York (1927), Yeshivah Ohel Moshe in Bensonhurst (1928), and Yeshivah Torath Emeth in Boro Park (1929) emerged, each catering to the specific demographics of their communities while upholding the exacting standards of Torah learning.

Cities outside New York were much slower to adopt this model. Following the 1917 opening of Talmudical Academy in Baltimore by Rav Avraham Nachman Schwartz, 20 years would pass before both Maimonides (Boston) and JEC (Elizabeth) began operations in 1937.

All of these institutions played roles in building Orthodox education in America into an enduring system, fortifying a community determined to function in modernity while remaining anchored in its sacred heritage. But this growth brought with it a host of challenges, particularly when it came to balancing religious integrity with the demands of a broader educational system.

As these institutions expanded, they faced increasing scrutiny from state education departments and accrediting agencies. To operate legally and provide their students with recognized diplomas, yeshivos had to meet stringent standards for general studies curricula, teacher certification, and classroom facilities — requirements that often clashed with their mission to prioritize Torah learning.

This tension was especially acute in areas like teacher training and subject hours. Many yeshivos struggled to find educators who were both qualified under state standards and deeply connected to the ethos of traditional Jewish education. Additionally, the need to dedicate significant time to religious studies often meant squeezing general studies into fewer hours, leading to questions about whether these schools were adequately preparing students for higher education and professional careers.

A pivotal moment in the history of American Orthodox Jewish education came in 1938, when some three dozen K-12 yeshivos from across the country came together to form the United Yeshivos Federation. This organization was established with two primary objectives: to address the growing challenges of accreditation and compliance with educational standards, and to create a centralized fundraising system that would distribute pooled resources to member institutions based on their size and needs.

Leading this ambitious initiative was Zvi Aryeh (Harris) Selig, widely regarded as the premier fundraising strategist in Orthodox circles. A product of the European yeshivah system, Selig had immigrated to America in 1896 and built a remarkable career as a freelance fundraiser. His accomplishments included raising millions of dollars for such critical causes as the Central Relief Committee during World War I, Keren Hayesod, and the monumental 1920s building campaign for the RIETS/Yeshivah College campus in Washington Heights.

Selig brought an innovative approach to the United Yeshivos Federation, departing from the traditional reliance on large donations from wealthy benefactors. Instead, he launched a groundbreaking grassroots membership campaign aimed at enlisting broad community support. For a single dollar, any Jew could become a member of the Federation and become eligible for a grand prize drawing of $10,000. Selig’s vision was to engage 100,000 Jews in New York alone, with the hope that many would contribute more than the minimum amount. This approach aimed not only to democratize the Federation’s fundraising but also to create a sense of communal ownership and responsibility for the future of Jewish education.

To drum up support for the campaign, Selig penned op-eds in the Yiddish press bemoaning the lack of support for Jewish education: “Instead of endeavoring like our forebears to transmit to our youth the spiritually rich principles of our faith in all their intensity, we have been satisfied with a bare minimum, amounting to nothing and leading to nothing.”

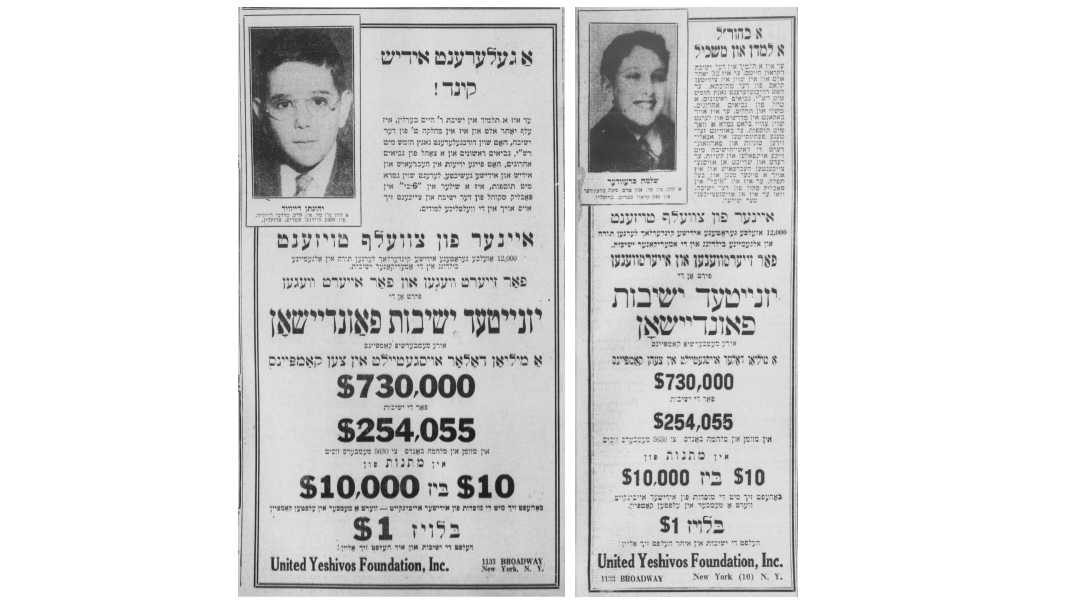

He also ran a series of ads profiling students at yeshivos that were Federation members. Two such students went on to become gedolei Torah: Rav Shlomo Brevda and ybdlch"t Rav Yonasan David.

Rav Brevda grew up in New York. Shortly after the Mir Yeshivah arrived from Shanghai, he went there to learn, developing a close relationship with the mashgiach Rav Chatzkel Levenstein. He subsequently moved to Israel, and dedicated the rest of his life to his two primary endeavors: studying and publishing works on the Torah of the Vilna Gaon; and inspiring masses on three continents, touching the hearts and minds of generations of individuals, spurring growth in Torah and yiras Shamayim.

Rav Yonasan David joined Yeshivas Chaim Berlin at a young age, and soon became a close student of his eventual father-in-law, Rav Yitzchok Hutner. Together with his wife, Rebbetzin Bruriah, they edited and published the works of Rav Hutner in the multivolume Pachad Yitzchok. Rav David continues to serve as the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivah Pachad Yitzchok in Yerushalayim.

While the United Yeshivos Federation achieved notable success in its fundraising campaigns and provided crucial support for more than a decade, it struggled to keep pace with the exponential postwar growth of the yeshivah day school movement. This surge, catalyzed by the founding of Torah Umesorah in 1944, placed ever-increasing financial demands on the system. By the mid-1950s, as the needs of the growing network of schools outstripped the Federation’s resources, the organization was ultimately forced to close its doors.

More Than Just Luck

The winner of the $10,000 grand prize in the 1941 United Yeshivos Federation drawing was none other than Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyoff (1888–1966), one of America’s foremost Torah educators in the first half of the 20th century. A distinguished talmid of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer and a chavrusa of Rav Aharon Kotler during their time in Slutzk, Rav Poleyoff served as a rosh yeshivah at RIETS for over 45 years and authored several seforim. Among his many esteemed talmidim was Rav Mordechai Gifter, whose correspondence with his rebbi was preserved and published in 2010 by their families in the fascinating sefer Milei D’Igros.

Tishah B’Av Salvation

In the mid-1940s, the New York State Board of Regents sought to revoke the accreditation of yeshivah day schools unless they taught general studies in the morning hours. The Board of Regents held a hearing in Albany and invited representatives of the yeshivos to attend.

Among those who joined Harris Selig on the delegation to Albany were RJJ’s president, Irving Bunim, attorney Louis Gribetz, future Congressman Herbert Tenzer, and other rabbinic and lay leaders. According to Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock, they went with the blessing of Rav Aharon Kotler, who felt that failure to convince the Board of Regents to permit morning Torah studies would cause a bechiyah l’doros (lamenting for generations to come).

As it turned out, the hearing took place on Tishah B’Av. Encouraged by Rav Aharon Kotler, the delegation went to Albany regardless, but were told to remain unshaven and wearing sneakers.

When the Board’s attorney, Susan Brandeis, daughter of Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, saw their unkempt appearance, she asked sharply, “Is this a way to come dressed to a Board of Regents hearing?”

Tenzer jumped to his feet. “Mr. Chairman, may I explain the reason for this? Today is the anniversary of the destruction of the Temple. These men and I were at the synagogue praying at six this morning. We are not permitted to eat, drink, shave, or wear leather shoes for a period of 25 hours. It is a tragic and trying day for us, but because of our respect for this Board, we did not apply for a postponement. We want you to know how much we wanted to attend this hearing, and we also want you to know why we appear as we do.”

Owen Young, chairman of the Board of Regents and president of General Electric, said quietly, “Miss Brandeis, I think you owe these gentlemen an apology.”

Tenzer’s heartfelt presentation was the best possible introduction for his group’s position, for prior to the hearing, the Board of Regents had been hostile toward the yeshivos’ cause. Tenzer’s remarks underscored his colleagues’ integrity, and the members of the Board of Regents kept an open mind.

The Board felt all parochial schools should offer general subjects in the mornings. It maintained that students’ minds were more alert then, and that secular studies were more important than religious subjects. Bunim argued that they needed Hebrew teachers to supervise and conduct morning services. If the students then proceeded to secular classes, the Hebrew teachers would have to be dismissed and brought back later in the day.

“The cost,” Tenzer said, “would be prohibitive. We would have to triple the payroll.”

Bunim offered statistics showing that despite years of secular studies in the afternoons, yeshivah students had collectively outscored their non-yeshivah peers in Regents examinations.

Tenzer added, “The children at our yeshivos have a zest for knowledge. Their minds are sharpened by studying Torah. The analytical training they receive each morning enables them to absorb knowledge throughout the day.”

Duly weighing the evidence, the Board of Regents exempted the yeshivos from teaching general subjects in the mornings.

(Story excerpted from A Fire in His Soul: Irving M. Bunim and His Impact on American Orthodox Jewry, by Rabbi Amos Bunim.)

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1046)

Oops! We could not locate your form.