More Beloved than Wine

The words of Chazal are even more beloved and sweeter than the ‘wine’ of Torah”

C

lose to 40 years ago, I was witness to what seemed at the time an insignificant conversation between one of the yungeleit in the kollel in which I was learning and an attendee at his beginners’ Gemara shiur.

They were learning about the melachos of Shabbos and were studying the details of meleches koseiv, writing. The halachah is that writing two letters in order on Shabbos makes one liable min haTorah for writing. However, if one writes only one letter, and that letter is the final one in a book of Tanach, he is liable min haTorah all the same. The reason for this is that the writing of a letter that concludes an entire sefer of Tanach is significant enough to qualify it as meleches machsheves, which constitutes chillul Shabbos.

The novice student, an intelligent gentleman, asked the rebbi why the ending of a sefer of Tanach is different from the ending of any secular book. The yungerman, a very sharp talmid chacham, explained that the holy sifrei Tanach are the word of Hashem, written with precision and without a solitary extra word or letter. When it is over, it is absolutely over.

The ending of a secular book, on the other hand, is arbitrary. If the author of Moby Dick, for example, had decided to write another chapter, there was nothing to stop him from doing so. Therefore, writing the concluding letter to Iyov, Shmuel, or any other sefer Tanach, has a special significance and qualifies as a melachah. Moby Dick is not Torah min haShamayim and there is nothing legislating its end. I was impressed with this talmid chacham’s quick wit and how he applied his bekius in the divrei chol of his youth to help him teach fundamentals of the Torah Hakedoshah.

This story comes with an amusing footnote, which is probably why I remember the story so well. Just a few weeks later, one of the attendees of another of this yungerman’s shiurim wanted to show his appreciation for the devotion the rebbi had for his students and presented him with a beautifully gift-wrapped Chanukah present... a copy of Moby Dick.

I took it as a siman min haShamayim (as did he) that this talmid chacham was right on the mark with his ability to make Torah alive to a newcomer and was being encouraged to continue his avodas hakodesh, which he does with great expertise till today, bringing the devar Hashem to thousands all over the world.

This whimsical anecdote can perhaps cast some light on a cryptic line in Gemara (Yoma 29a) that tells us, “Purim was the last of all (public) miracles.” The Gemara counters, “But wasn’t there Chanukah?” And the response is that Purim was the last one to be written (as part of Tanach, in Megillas Esther).

This passage begs for an explanation. What is the difference if it was written or not? A miracle is a miracle! We may suggest that the idea of a book, particularly one of the five Megillos, is, as stated above, a finite work in which the story ends with the concluding sentence. This was Purim and Megillas Esther, the story of Haman’s attempt at genocide of the Jewish People and our miraculous salvation. There was a physical existential threat to the Jewish nation, and it was thwarted in the merit of our tefillos and acts of teshuvah.

Chanukah, on the other hand, was not given to be written down, for that story never ended. That was a battle of spiritual survival, Yavan’s desire to Hellenize us all and force us to adopt their culture and lifestyle. We were granted a reprieve during the period of the Chanukah miracle, but that battle never truly ceased. It could not be written down as a book because a final chapter has yet to be written. And the war goes on.

Rav Chaim Stein ztz”l, the Telsher Rosh Yeshivah, pointed out that the Gemara investigates what sin might have caused the decree against the Jewish nation before the miracle of Purim. Yet when it comes to Chanukah, we find nothing of the sort in the Gemara (although some later commentaries, such as the Bach, offer opinions). He suggested that the challenge we faced at that time was really nothing new at all. It was the time-honored battle between the Sitra Achra and the power of kedushah. Chazal didn’t have to ask why it came; it is as old as Yaakov and Eisav and will always be a battle to be fought until Mashiach’s arrival. It is indeed the war that never ends.

Just to illustrate how crucial our resolve must be to come out victorious in this eternal battle, Rav Nosson Wachtfogel, the Lakewood Mashgiach, shared a tradition he has ish mipi ish, going back to the great Rav Yehoshua Leib Diskin — that in the last war before Mashiach’s arrival, all erliche Yidden will be saved. Rav Yehoshua Leib defined “erliche” as those who have separated themselves from the nations of the world by avoiding the products of their culture, such as their newspapers, their music, and their books.

We may sometimes be hard-pressed to tell the difference between their cultural products and ours. Could we honestly say we are among those whom Rav Yehoshua Leib was talking about?

Some years, such as this one, find society at large celebrating their holiday season exactly when we are observing ours. The various ads and promotions in the secular media as well as our own evoke bars of the seasonal song, “It’s beginning to feel a lot like Chanukah, everywhere you go,” although their version substitutes something else for Chanukah. We are bombarded on the heels of Black Friday to spend money with reckless abandon, often on things we do not need. There is a ruach in the air to spend, spend, spend.

I recall a comment made to me by a friend who owns a Judaica store, that when our two holidays coincide, business is way better, since people are in the mood to buy. Nebach, even our moods are influenced by the culture around us that places such a priority on acquiring “stuff.” This did not come from Mattisyahu and the Chashmonaim, we can be sure of that. They were moser nefesh to overcome Yavan and all that it represented, and not allow their world into ours.

We may think that we don’t really buy into the season at all and that we have indeed resisted Yavan’s advances. This presumption may be challenged with the following humorous but thought-provoking story about a little boy who went shopping with his big sister in a large department store and encountered the Bearded One in his red suit entertaining the children on his lap.

Wanting part of the fun, the child walked up and sat on the man’s lap and was asked what he wanted for the holiday.

“A Shas!” the budding talmid chacham answered.

Without missing a beat, the man replied, “A gezunt oif dein kup!”

Needless to say, the boy left without his Gemara. This may sound like a harmless anecdote, but it reminds us of our responsibility to teach our children to resist the allure of the society that surrounds us.

The Ponevezher Rav offered a novel insight to answer a very obvious question on the al hanissim prayer that we recite on Chanukah as well as on Purim. After we thank Hashem for the miracles and salvation, “al hanissim v’al hapurkan,” we add “v’al hateshuos v’al himilchamos — the salvations and the wars.” Do we really want war?

Some, including Rav Yosef Nechemiah Kornitzer ztz”l, have suggested that after experiencing a yeshuah from a tzarah such as war, one might be inclined to have wished the tzarah never came in the first place. The true eved Hashem realizes that if the tzarah was a vehicle for him to eventually appreciate Hashem’s hashgachah in the yeshuah, then it was all worth it. We therefore thank Hashem for that opportunity, even for the milchamah.

The Rav had a different perspective, which dovetails with the vort we began with above. It is still a little too early to thank Hashem for the victory, since the war against Yavan was really about kedushah versus tumah. Total victory will only be achieved when Mashiach arrives, and evil will be completely eradicated. It is hardly the time to pat ourselves on the back and take a victory lap.

But there is one thing to still be thankful for in this regard, and that is the determination to keep on fighting, even though the battle is tough. When the powers of tumah are raging, we refuse to stop fighting the good fight, but choose to continue the battle until we merit the day when kedushah will be victorious for good.

The Rambam, at the end of Hilchos Chanukah, writes that the mitzvah of ner Chanukah is “mitzvah chavivah ad me’od — a very beloved mitzvah.” This terminology is not typical of the Rambam’s style anywhere else. He doesn’t rank the popularity of mitzvos. Furthermore, what is this chavivus of which the Rambam speaks?

Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach referenced the Gemara in Yoma we quoted at the outset stating that the Chanukah story was not to be written in a formal megillah. He explains that this is because the whole point of the Chanukah miracle is to emphasize and strengthen our emunah in Torah shebe’al peh, the oral transmission of Torah.

This is borne out by the following question. How could the oil in the Beis Hamikdash become defiled in the first place? The Gemara teaches us (Pesachim 17a) that all sanctified liquids, such as the blood used to sprinkle on the Mizbeiach, the water used for the libations, as well as the oil for the Korban Minchah are always pure. That being the case, then based strictly on the written Torah, they didn’t require a miracle at all.

Furthermore, as others point out, the entire issue of the eino Yehudi defiling the oil is also only d’Rabbanan in nature. The neis of Chanukah was intended to preserve the integrity of the institution of Chazal and Torah shebe’al peh and our belief in them, and to show how beloved they were to Hashem.

We may also add the well-known maamar Chazal that tells us, “Chavivin divrei sofrim miyeinah shel Torah — The words of Chazal are even more beloved and sweeter than the ‘wine’ of Torah.” Since the Chanukah miracle publicized our commitment and belief to Torah shebe’al peh, it is only fitting that it davka not be written, but left to oral tradition. This is the “chavivus “ the Rambam is referring to, the love we displayed toward all things Torah shebe’al peh — a love so precious to Hashem that He made a miracle to reinforce that commitment and belief.

It is written in Sefer Minhagei Chasam Sofer that on Chanukah, more so than on other days, the Chasam Sofer was very particular to learn Torah and was perturbed by those who wasted their time on frivolous pursuits. He said that it is the strategy of the yetzer hara to prevent people from avodas Hashem and talmud Torah on Chanukah, a day reserved for thanks and praise to Hashem, because secrets of the Torah were given to Moshe Rabbeinu on the days that were destined to become Chanukah. We may add that those secrets are the epitome of Torah shebe’al peh.

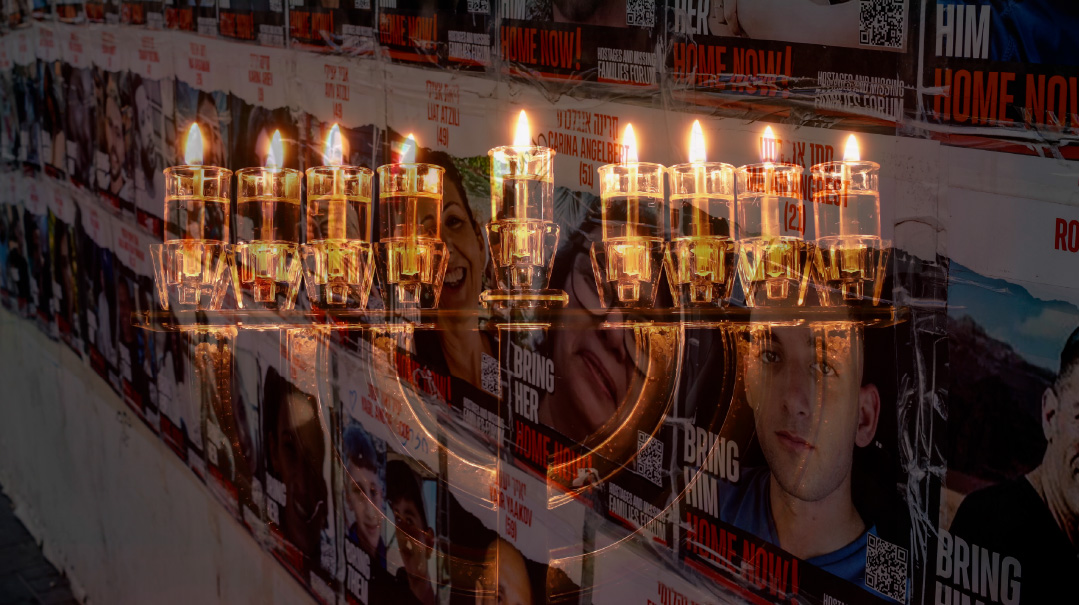

AS we stand around our menorahs and take in the light of our tiny flames that pushed away the “choshech zu Yavan,” the darkness of the Greeks who dimmed our eyes with their wicked decrees against our Torah life, we should share our own renewed commitment to our chachamim as well, and the Torah shebe’al peh they nourish us with for our day and age.

And as we view the decadence to which the world around us has sunk, as spiritual heirs to Yavan and those who follow their ways, let us thank Hashem for lighting our path to a life of taharah, kedushah, and love of Torah and mitzvos. There is nothing more beloved than that.

Rabbi Plotnik, a talmid of the yeshivos of Philadelphia and Ponovezh, has been active in rabbanus and chinuch for 25 years and currently serves as ram in Yeshivas Me’or HaTorah in Chicago.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1042)

Oops! We could not locate your form.