Until the Shaded Light Shines

Oppressed and exiled, Rav Levi Yitzchak Schneerson never let the flame go out

Photos: Derher, Anash, Kehot, Chabad Library, Shalom Ross

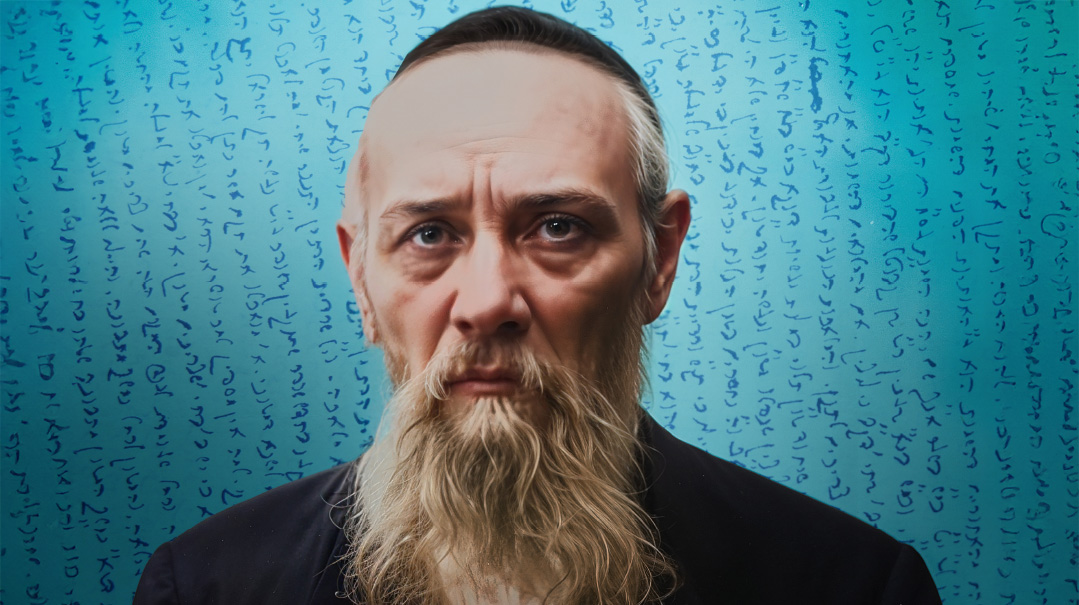

Rav Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, known simply as “Reb Leivik” and the father of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, suffered at the hands of the NKVD and died in exile, surrounded by a small kehillah he cobbled together deep in the Soviet wilderness, with his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, at his side. In her diary, she begs for her husband to be memorialized through his Torah — but how, when his thousands of folios and manuscripts were seized by the Russian oppressors?

ON the 20th of Av this past summer, several hundred Jews gathered in a little cemetery in the remote Kazakh city of Almaty, in the foothills of the Trans-Ili Alatau mountains. They made their way to a weathered structure erected over a lonely grave. Their destination: The unlikely resting place of a towering tzaddik, a genius whose commentaries and elucidations demonstrate a mastery of all primary elements of Torah. In a way, their wearying journey was an appropriate commemoration for this great tzaddik. Bitter exile defined much of his legacy, one that continues to remain an arcane mystery to this day.

A few weeks prior, the third day of Tammuz marked the 30th yahrtzeit of this great tzaddik’s son. This event was celebrated by tens of thousands throughout the world, even acknowledged in various halls of government, as lines of buses and streams of visitors crowded the streets outside his burial place.

Such is the yearly commemoration of the passing of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rav Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who easily lists among the most influential rabbinical leaders of the 20th century. But few are familiar with the life story of his father, a brilliant thinker whose rabbinic position and spiritual influence seemed all but over when the Communists wrenched him away from his home and sentenced him to exile.

His name was Rav Levi Yitzchak Schneerson, and he was known simply as “Reb Leivik.” The primary remaining insight into the depth of his personality comes from the extensive writings he left behind (although they are just a fraction of his vast writings, most of which were confiscated by the Russians).

In these lengthy essays, Reb Leivik comments on the Zohar, the Tanya, and many excerpts from the Gemara, primarily those of aggadic nature. He quotes hundreds of sources throughout these works.

Almost all from memory — he wrote them while in exile in Kazakhstan.

Curiously, these notes are written in inks of various colors. That is because the ink he used was curated by his wife, Rebbetzin Chana, using a variety of herbs and other ingredients.

In one of his surviving pieces, Reb Leivik addresses a gemara in Shabbos (22a) which states that just as one cannot utilize the Chanukah light for his own benefit, so too, he cannot utilize the succah decorations for his own benefit. Reb Leivik explains the association. A succah provides shade. A candle provides light. “Where there is no light, there cannot be shade,” he writes.

Reb Leivik’s life was obscured by a thick wall of shade.

But behind it, no doubt, there stood a blinding light.

Memorial in Print

SO

writes Rebbetzin Chana Schneerson, the wife of Reb Levi Yitzchak, in a diary where she recorded detailed descriptions of much of their life together. She stood by his side as he studied uninterrupted for years, and watched as he wrote an incalculable amount of chiddushei Torah. She was there when the Russians invaded their home, whisked her husband away, and seized all his writings.

In this entry, she describes her deep yearning that her giant of a husband be memorialized through his Torah. And she was right: This would be the most fitting tribute, since any glimpse into Reb Leivik’s essence must come via the vistas of Torah he pried open.

Most of Reb Leivik’s writings are steeped in Kabbalah and not readily comprehensible to the masses. I was first introduced to Reb Leivik’s Torah by my friend, Rabbi Eli Simpson. Reb Eli is a brilliant talmid chacham and he graciously invited me to weekly sessions in which we learn Reb Leivik’s Torah. Nearly all of it is well beyond my grasp, but part of the wonder of Reb Leivik’s Torah is that you don’t need to fully understand it to be impressed by its magic.

Anyone who has learned Gemara is aware of the frustrating sense of inability when confronted with an “aggadeta Gemara.” These portions of Talmud can describe an instance on Purim where “Rabbah rose and slaughtered Rav Zeira” or how “Korach’s wealth was so extensive that the keys to his treasury needed to be carried by three hundred white mules” or “a precious stone hung around Avraham Avinu’s neck which brought healing… and was later hung from the sphere of the sun.”

Despite the multitudes of commentaries who weigh in on these enigmatic episodes — some working to explain them on a basic level, others seeking to derive a deeper message — the student is always left with a lingering sense that there is more, something magnificently profound lying within the obscure passages. Indeed, the Baal HaTanya writes that “the majority of sodos haTorah lie within aggadeta Gemaras.”

Reb Leivik produced an enormous amount of literature explaining these excerpts. Ten pages of fine print, blending dozens of sources from various Kabbalah seforim, will work to explain a few short lines of Gemara.

At times, his focus isn’t on aggadeta per se. Every now and then, the Gemara will insert a seemingly irrelevant, sometimes bizarre-sounding detail, into the midst of a halachic discussion. An Amora might be “leaning on a doorpost” while pondering a certain question, Tannaim might be “on their way to purchase a cow for Rabban Gamliel’s son’s wedding” when they discussed a particular concept.

What is the purpose of these descriptions? Reb Leivik will string together a litany of quotes from kabbalistic sources to shed light on this one obscurity.

The gemara in Megillah teaches that when the sofer writes the word “Vaizasa” (one of Haman’s ten sons), the “vav” should extend like a “steering oar of a ship.” Reb Leivik has a vast essay explaining these few words.

No line in Chazal is taken for granted.

A trademark characteristic of Reb Leivik’s style is to find significance in the names of the Tannaim and Amoraim. Rav Chisda, for example, relates to the middah of “Rav Chesed” (one of the Thirteen Traits of Mercy). The root word of “Ashi” is “eish” (fire) and thus the Amora Rav Ashi relates to the middah of gevurah, which is associated with fire. Conversely, the Amora “Ameimar” relates to chesed, as his name stems from the word “amirah” which, as we’re taught, is a soft form of speech, an expression of chesed. Rava relates to the reish, veis, and alef of Avraham Avinu’s name.

In his commentary on a piece of aggadeta presented by Rav Dimi, Reb Leivik expounds upon the idea of “lev, lev — two hearts.” He then concludes by commenting that “Dimi” is gematria “lev lev.”

And while his Torah plumbs the depths of Kabbalah and chassidus, his life story carries lessons in steadfast emunah, unbending endurance, and fearless commitment to avodas Hashem.

I am no writer and in general who am I and what am I? Nevertheless, I am almost always alone and every individual is considered a small world. I have no one with me with whom to share my feelings other than my son, may he live long years with great health and success. On the 28th of this month I turn 75 years old. This is a number that has some general significance of its own, and particularly in light of what I’ve endured in recent years. The life of my husband of blessed memory was tragic and the same is true after he left this world. It would be desirable that there be some memorial to him. It appears to me that some of his writings could be published.

Ocean and Tributaries

If the Baal HaTanya, Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi, was an ocean of Torah greatness, his children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren are a webwork of lakes, rivers, streams, and canals. The lineage of the seven Lubavitcher Rebbes flow through his son, Rav Dovber (the Mitteler Rebbe). The Mitteler Rebbe passed the mantle of leadership to his son-in-law and nephew, Rav Menachem Mendel, known as the Tzemach Tzedek. (He was also the grandson of the Baal HaTanya, as his mother, Devorah Leah, was the Baal HaTanya’s daughter.) It then went from the Tzemach Tzedek to his youngest son, Rav Shmuel, known as the Maharash, and from there to the Maharash’s son, Rav Sholom Dovber — the Rashab. The Rashab’s son, Rav Yosef Yitzchak, or the Rayatz, was the next Rebbe. The Rayatz’s daughter, Chaya Mushka, married Rav Menachem Mendel Schneerson, who would become the seventh, and final, Rebbe.

He has no acronym. He is simply known as “the Rebbe.”

But along with those seven Rebbes, there were also sons, sons-in-law, and grandsons taking up various positions of rabbanus, or leading smaller chassidic courts, throughout locales which today are Eastern Ukraine, Western Russia, and Belarus.

An exception was the Tzemach Tzedek’s oldest son, Reb Boruch Sholom. Reb Boruch Sholom was a brilliant talmid chacham and tremendous masmid, yet he never assumed any position of authority. He remained in the town of Lubavitch and dressed like the common folk.

But his father saw the greatness within the purported simplicity. According to legend, the Tzemach Tzedek commented that in the merit of Reb Boruch Sholom’s demurral of any honorary title, he would merit a descendant who would serve as a leader. He then cryptically concluded by quoting the pasuk in parshas Lech Lecha “v’dor revii yashuvu heinah — and the fourth generation will return here.”

Reb Boruch Sholom had three sons: Reb Mordechai, Reb Levi Yitzchak, and Reb Yehuda Leib. Reb Levi Yitzchak passed away at a young age but left behind a son, Boruch Shneur. Boruch Shneur married Zelda Rochel Chaikin and they had three sons — Levi Yitzchak (named for his grandfather), Shmuel, Sholom Shlomo — and a daughter named Rada Sima.

It was Rav Levi Yitzchak who would have a son named Menachem Mendel, later to marry the daughter of the Rayatz and become Rebbe.

Four generations down from Reb Boruch Sholom.

V’dor revii yashuvu heinah.

He would preside over an exploding chassidus and a sweeping global movement of kiruv rechokim. Before packed crowds of chassidim he would share Torah from the six rebbes who preceded him, the beaming strokes of wisdom that forged his own path and vision.

But for a period of time, he delivered a weekly maamar in which he expounded upon an excerpt found in the newly published set of Likkutei Levi Yitzchak.

The insights of the Rebbe’s father, the brilliant light darkened by a thick wall of bitter shade.

Born to Lead

Levi Yitzchak was born on the 18th day of Nissan, 1878 to Reb Boruch Shneur and Rebbetzin Zelda Rochel Schneerson. They lived in Podrovnah, a town near the city of Gomel, Belarus.

He studied under his uncle, Rav Yoel Chaikin, who had been a close chassid of the Tzemach Tzedek as well as the Maharash. Not much is documented of Reb Leivik’s childhood other than a letter penned by the Rayatz in which he writes, “Already from a young age, his extraordinary talents were discovered.”

It was the Rashab who suggested Reb Leivik for Chana, the daughter of Reb Meir Shlomo Yanovski, rav of Nikolayev. On the 13th day of Sivan, 1880, at the age of 22, Rav Levi Yitzchak Schneerson married Chana Yanovski.

Supported by his father-in-law, Reb Leivik learned 18 hours a day. His chavrusa, Reb Shmuel Grossman (a native of Nikolayev and talmid of the Rashab) described how Reb Leivik went to sleep sometime around 5:00 a.m., after having donned tefillin and reciting Krias Shema shel Shacharis. By 9:00 he was awake, davening Shacharis to begin another day of learning.

The Rebbe, when describing his father’s learning habits as a youngster, mentioned that Reb Leivik desired to receive semichah from the litvishe gedolim, such as Reb Eliyahu Chaim Meisel, the rav of Lodz, and even Rav Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk, one of the generation’s leading geonim. Apparently, following a lengthy discussion in which Rav Chaim Brisker was deeply impressed by the young chassid’s knowledge and intellect, he commented, “Gevald Reb Leivik, aza gutte kup, in vuhs hut ihr areingelegt? — Gevalt, Reb Leivik, such a good head, what have you involved it in?!”

It was a light critique of Reb Leivik’s dedication to Toras hachassidus as opposed to a singular focus on Gemara, Rishonim, and Acharonim.

It was the eighth year that we were living in the home of my parents, who supported us while my husband studied Torah full-time. The time had come to consider a source of livelihood.

Rebbetzin Chana wrote this diary entry in 1908. By this time, Reb Leivik and Rebbetzin Chana had two children, Menachem Mendel and Dovber. Reb Leivik’s reputation as an exceptional talmid chacham was already widespread, and he received multiple offers for positions of rabbanus. Ultimately, he accepted an offer presented by the city of Yekaterinoslav.

This development came on the heels of one devastating era for the Jews of Russia and at the onset of another.

The 20th century was ushered in just five years after the death of Czar Alexander III in 1894. It was the Czar’s policy that was implemented into the infamous “May Laws,” which placed residency and business restrictions on Jews throughout the Russian Empire.

In the words of his minister, Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev, the government’s goal was that “One third [of the Jews] will die out, one third will leave the country, and one third will be completely dissolved in the surrounding population.”

For years, the Jews were subject to the most devastating atrocities as they stood powerless against the rapidly increasing number

of pogroms.

A New York Times article describing the First Kishinev pogrom of Easter, 1903 wrote, in part:

The anti-Jewish riots in Kishinev, Bessarabia [modern Moldova], are worse than the censor will permit to publish. There was a well laid-out plan for the general massacre of Jews on the day following the Orthodox Easter. The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, “Kill the Jews,” was taken up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep…. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded. Those who could make their escape fled in terror, and the city is now practically deserted of Jews.

The rabid waves of anti-Semitism took on a different form following the October Revolution. On October 25, 1917, the Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin, ousted the sitting government and seized power over all of Russia.

Under the far-left views of Bolshevism, all men and women were to be treated equally — including Jews. This liberal policy was celebrated by many within the terrorized Jewish communities and a significant number of Jewish youth enthusiastically joined the Red Army, founded by Leon Trotsky.

But along with the ardent insistence on equality came a more subtle, but just as venomous, enemy. Secular, assimilated Jews were stationed at high-ranking government positions with the stated instruction to actively discourage religion. By 1919, Jewish communities were being dissolved, properties confiscated, shuls and schools shuttered. The speaking of Hebrew was outlawed, as was the printing of Jewish books.

Yekaterinoslav of 1908 was very much paradigmatic of this evolving reality. It was a large city with a diverse Jewish community consisting of some 40,000 members. (Yekaterinoslav was later named Dnepropetrovsk and is today’s “Dnipro,” Ukraine’s fourth-largest city, located on the Dnieper River in central Ukraine.) The assimilation rate was quite high by that point; Russian was the spoken language in many Jewish homes, and some Jews had even converted to Christianity. It was in this tumultuous environment that Reb Leivik was graced with the badge of rabbanus.

“Take My Kapoteh”

Reb Leivik’s appointment in itself brought about a fresh wave of contention. The Jewish population of Yekaterinoslav at the time consisted primarily of five groups: chassidim, misnagdim, maskilim, Zionists, and the upper-class, wealthier society. The chassidim supported the appointment of Reb Leivik; all other factions opposed it.

This opposition was well-founded. Beginning with the Baal HaTanya’s fierce objection to Napoleonic rule and whatever liberties it presented, Eastern European progressive Jews felt disdain and hostility toward the proudly traditional Chabad chassidus.

Those in the opposition preferred a rav named Rav Pinchas Gelman, who was not a chassid and would presumably be less outspoken against modern, liberal views.

In her diary, Rebbetzin Chana describes how intense the controversy was: “A dispute broke out in the city’s Jewish community, with parties and families who once lived in peace becoming bitter rivals.”

In a near-miraculous turn of events, a man who should have been Reb Leivik’s fiercest opponent became one of his most trusted supporters. Sergei Pavlov Fallei was the most respected member of the Zionist party’s local chapter. After the initial meeting in which the Zionists formally decided to oppose Reb Leivik’s candidacy, Fallei approached several chassidim and expressed a desire to meet the rabbi. Upon meeting Reb Leivik, Fallei announced that “nothing should stop Schneerson’s appointment” and that “such a special person should not be permitted to go anywhere else.”

Fallei was so taken by Reb Leivik that he submitted his resignation from the Zionist party and led the fight in support of Reb Leivik’s appointment as rav. Ultimately, an agreement was reached in which both Reb Leivik and Rav Gelman became official rabbanim, servicing different areas within the city.

As rav, Reb Leivik’s first step was a campaign for the reconditioning of the mikveh, which was old and in disrepair. He called a meeting with community leaders where he expressed the urgency of the matter. But their response was tepid as they claimed not to have sufficient funds. Reb Leivik stood up and removed the new kapoteh he’d just acquired in honor of his rabbanus. “Here,” he said, “sell this and use the money toward rebuilding the mikveh.”

With time, Reb Leivik won over many of his previous opponents. Rebbetzin Chana describes how they now listed among the many Jews who came to consult with him in his office, and the increasingly larger audiences drawn to his derashos on Yamim Tovim.

The wave of radical leftism continued to grow and, along with it, severe governmental pressure to abandon all religion. Reb Leivik, however, would not tolerate any compromise. Rebbetzin Chana writes of a time when the government made all citizens fill in a questionnaire. One of the questions was “Do you believe in G-d?”

Reb Leivik realized that many were answering in the negative to avoid any harsh consequences. He ran from shul to shul fiercely proclaiming that it was forbidden to supply such a response.

“Anyone who wrote ‘no’ is a kofer b’malchus Shamayim!” he declared. “They must amend their response!”

Many Jews followed his directive, and the government agency, not knowing what to do with hundreds of submissions openly confirming belief in G-d, invalidated the questionnaire and issued a new one.

Later, Reb Leivik was confronted by government officials.

“Why did you do that?” they demanded.

Reb Leivik kept his composure. “I did it for the good of the Motherland!” he said. “You want your citizens to be honest, don’t you?”

In 1983, the Rebbe shared a story that hadn’t been made public until then. Under communist rule, all factories were considered property of the government. This included flour manufacturing plants. As Pesach approached, the government was aware that Jews would not purchase matzah unless it was stamped with rabbinic certification. The government, however, was not willing to allow its production to be overseen by a rabbi. Reb Leivik was called into a meeting where he was informed that he would be issuing a kosher certification to all the flour — no inspection necessary.

Reb Leivik refused, insisting that such certification would only be issued if he was allowed oversight. The officials made it clear that such obstruction would be deemed interference with government affairs and a serious offense. Reb Leivik wouldn’t relent. His response was reported to higher level authorities and ultimately reached the Kremlin. Inexplicably, the Kremlin issued an order to cooperate with all Reb Leivik’s demands.

Snatched by the NKVD

During this time, Reb Leivik and Rebbetzin Chana raised their three sons, Menachem Mendel, Dovber, and Yisroel Aryeh Leib. They sent the boys to learn under the tutelage of a local melamed, Reb Shneur Zalman Vilnekin.

All three sons excelled and their diligence was such that their mother had to tear them away from their studies at mealtimes. When Menachem Mendel reached the age of nine, his melamed informed Reb Leivik that he could no longer stimulate the boy’s intellect.

This melamed later shared the events of one Shabbos in Yekaterinoslav. Reb Leivik was delivering a derashah steeped in kabbalastic concepts. One attendee interrupted. “Who is the Rav speaking to? No one understands!”

“There is one bochur in the corner who understands,” Reb Leivik responded.

There stood Menachem Mendel.

The second son was Dovber, known as Berel. Although Berel was a brilliant young man, with a more outgoing personality than his older brother, he led a tragic life, struggling with various medical conditions.

Sometime during World War II, he was in a local hospital when the Nazis invaded. The Nazis ordered all patients out of the hospital and murdered the Jewish ones before tossing their corpses into a mass grave.

Little else is known about Dovber.

The third son, Yisroel Aryeh Leib, was a remarkable genius. A chassid named Reb Nochum Gorelnik was learning in yeshivah and wished to meet the great gaon, Reb Leivik Schneerson. Reb Leivik was deeply impressed by the young man and invited him to his home for supper. The two older sons were not yet home but he noticed the youngest one sitting at a table, his head leaning over his arms. Nochum turned to Reb Leivik. “I’ve never seen a child playing such a game,” he said.

“Game?” replied Reb Leivik. He inserted a hand under his son’s bent-over position and removed a mishnayos. “Please tell me what you learned,” he said.

The young child proceeded to explain the entire mishnah. With the spread of Communism in 1931, Yisroel Aryeh Leib moved to Berlin where he lived with his brother, the future Rebbe. Two years later, he immigrated to Eretz Yisrael, married, and had a daughter. A professor of mathematics, he passed away in England in 1952, and at the request of the Rebbe, who maintained a close relationship with him, was buried in Tzfas.

As the years stretched on, the three sons were no longer living at home, and Reb Leivik and his wife dedicated themselves fully to servicing the many needs of the local Jewish community in Yekaterinoslav.

Sometime around Purim of 1939, Rebbetzin Chana noticed two young men spending hours outside the home, clearly observing the goings-on with interest. In her diary, she describes how, on Purim, a festive farbrengen was held in the home and, upon its conclusion, the participants began to trickle out, a few at a time, to avoid arousing suspicion. Yet again, Rebbetzin Chana noticed the two men outside, watching intently. She had no doubt that these were agents of the NKVD (the Soviet Union’s secret police and interior ministry and forerunner of the KGB).

At approximately 3:00 a.m., on the ninth of Nissan, loud knocks were heard in the Schneerson home. Rebbetzin Chana opened the door to find four NKVD agents.

“Where is Rabbi Schneerson?” one of them demanded.

Rebbetzin Chana went to inform her husband of what was happening. In the meantime, the agents entered their home and began a thorough search. They located Reb Leivik’s thousands of pages of notes, his semichah certificates, and correspondence with other rabbanim. All were confiscated. The agents also confiscated various artifacts and handwritten notes passed down from the earlier Lubavitcher Rebbes. Also found and seized was a petition from the Jewish community in Yaffo appealing to Reb Leivik to emigrate and assume the position of Chief Rabbi. Along with the petition were visas for the whole family.

The search continued for three hours. Then the guards announced, “Rabbi Schneerson, get dressed and come with us.”

Since Pesach was approaching, Reb Leivik requested permission to take a package of matzos with him. This was granted. As Reb Leivik prepared to leave, he turned to the people who’d gathered in his apartment (apparently the commotion had brought neighbors to investigate). “I will be taken away now,” he said, “and Chazal teach us that one must part from his friend with a devar halachah.” He proceeded to share a Torah thought before being led outside to the waiting car.

Yisroel Adamski, who was a child at the time, remembered how the news of the arrest began to circulate the following day.

“Some tried to arrange a protest,” he said. “But the NKVD came with heavy weapons. If we could have had a protest, I am convinced that many of the non-Jews would have joined as well.” That was how well-respected Reb Leivik was.

Prison Travails

Reb Leivik was initially confined in the NKVD headquarters in Yekaterinoslav. He was then sent to the Narkumvski prison in Kiev, where he underwent grueling interrogations. Rav Aharon Yakov Diskin, who was the rav in Lyuban, was in the same prison as Reb Leivik. “Who could withstand such hardships?” he said later when describing what Reb Leivik had undergone. “Very few — and one of them is Rav Levi Yitzchak.”

(In a stunning letter that Reb Leivik wrote many years later, he described how he served time in five different confinements, including prison and exile. “Ani Levi Yitzchak ben Zelda Rochel,” he begins, “I, Levi Yitzchak ben Zelda Rochel, Higleisi al meshech hei shanim umeihem yashavti b’beis ha’asurim — I was exiled for a period of five years, and of those, I sat in prison.”

He ascribed the prison sentences as an act of Hashgachah pratis meant to cleanse him from sin. He then proceeded to write an extensive essay, explaining the kabbalistic depth behind each of the five stages of his infliction and how the decree was reflective of the gematria of his and his mother’s name.)

Not long after Reb Leivik was taken, the NKVD returned to the Schneerson home. Rebbetzin Chana describes this in her diary:

On a Shabbos day, two weeks after my husband was transferred back to Dnepropetrovsk, three NKVD agents paid a visit to our home to conduct another, more thorough search. All my husband’s books and manuscripts, which he guarded more than his very life, were confiscated and placed in their automobile. My impassioned pleas that they leave the books in the house led them to consult, by telephone, with their superiors, and in the end they returned the books to me. Alas, I could not save them from Hitler’s hands….

The purpose of the second search was to dig up additional material in order to make his crimes more grievous. Exactly what material, I don’t know.

After the search I was summoned to the NKVD office, where they badgered me for several hours to disclose what I knew about my husband’s public Yom Tov talks, what I knew about his correspondence overseas, and what my children write to us, particularly my son in America [Reb Menachem Mendel]. In the end, despite all their intimidation, my answers offered them no new information, and the state of affairs remained unchanged.

(This entry suggests that the seforim were returned by the Russians and only later taken by the Nazis. The Rebbe, however, had stated clearly that the notes were taken, and possibly still held, by the Russians. It is possible that the Russians returned the seforim but retained the notes.)

In a different entry, the Rebbetzin describes how she spent five months trying to determine where her husband was being held. Her efforts bore little fruit. One day, she was notified that “Levik Zalmanovitch Schneerson” was being held in a certain prison, and she was even told his cell number. She was granted permission to send him food and money. She describes how she was overjoyed to learn that he was alive and that she would be able to supply him with whatever rations would be allowed.

Alas, it was not quite so simple. She was only permitted to send things on specific days, determined by a system arranged in accordance with the alphabet, and divided into rotations of ten days.

After the first time Rebbetzin Chana sent a package, she received a receipt with her husband’s signature on it. The second time she was permitted to send him food, however, was on Shabbos. Rebbetzin Chana prepared the food on Friday and arranged for a non-Jewish girl to transport it on Shabbos. She walked alongside the girl the entire way to the prison. They arrived at 7:00 a.m. and Rebbetzin Chana was told to wait. She did so — until 7:00 p.m, when Shabbos was long over. Finally, a guard emerged holding a note from which he read aloud: “Since today is Shabbos, I did not take the package.”

The Rebbetzin notes how this extreme caution not to benefit from possible Shabbos desecration came after his suffering for six months, living off bread and water, and knowing that he would not be permitted to receive food for another ten days. “One needs my husband’s resolve and tzidkus to do such a thing,” she writes.

From then on, the officers at the prison referred to Reb Leivik as “the man who won’t take packages on Shabbos.”

To the Ends of the Earth

Toward the end of Kislev 1940, Rebbetzin Chana was summoned to the NKVD headquarters. She assumed that the prison authorities would finally grant her permission to see her husband. She was wrong. Upon arriving at the headquarters, she was told to wait. After about one hour, she was called into a room where she found four officers sitting around a table.

“Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson has been sentenced to five years of exile in central Asia,” one of them said flatly.

He was referring to Kazakhstan, which was then a Soviet republic. Kazakhstan is an enormous landlocked territory, the ninth-largest country in the world, bordering Russia to the north and west, and China to the east. Under Soviet rule, it was used as a “dumping ground” where political prisoners could be conveniently detained. The vast landscape was also dotted with prisons and gulags where dissenters against the state were incarcerated, tortured, or left to die.

Kazakhstan was also home to a handful of Jewish communities. Over the years, Jews who had been forcibly conscripted into the Russian army and stationed in Kazakhstan had banded together to shape some form of community.

A shocked Rebbetzin Chana tried pleading with them. “How can someone so weak survive over there?!”

The impassive office responded in stony tones: “The conditions won’t be so bad and he’ll be allowed to keep his Russian citizenship.”

Rebbetzin Chana was also informed that, prior to her husband’s exile, she would be allowed to personally bid him farewell.

“But what will he eat?” Rebbetzin Chana implored.

“He will eat what we feed him,” the officer replied. “Throughout his time in prison he ate whatever we gave him.”

But later, a different officer sidled over to Rebbetzin Chana: “It’s not true,” he confessed. “Your husband didn’t eat anything we gave him.”

A few days later Rebbetzin Chana was finally allowed to meet with her husband. She was shocked and dismayed by his sickly appearance.

“I couldn’t imagine that just a few short months could affect his health and well-being so much,” she later wrote.

The first words Reb Leivik said were, “Baruch Hashem we can finally meet.” And then: “Was Rosh Chodesh one day or two days this month? I must know, because Chanukah is coming.”

Rebbetzin Chana was not informed of the date of her husband’s exile. After a short time passed, she was informed that he was in Kharkov. She set off for Kharkov where, once again, she was allowed to see him. They bade each other farewell and soon, Reb Leivik was put on a train for the monthlong journey to Kazakhstan.

Rav Avrohom Boruch Pevzner, who was a mashpia in Kharkov, had been arrested a few months prior to Reb Leivik. He was on the same train and described the terrible abuse to which Reb Leivik was subjected.

“He was extremely weak from his months in prison. There were points in the journey when we had to walk and Reb Leivik would collapse. The guards would set their dogs on him, forcing him to continue walking.”

Reb Leivik later commented that the most difficult part of the experience was that he couldn’t wash netilas yadayim. And while the passengers were severely dehydrated, whenever they did receive a small amount of water, Reb Leivik used his portion to wash his hands rather than to drink.

On the 15th of Shevat (1940), the journey came to a halt in a village called Shieli, which is located in the Kyzylorda Region, in southern-central Kazakhstan. The village was a wretched, mosquito-infested backwater, with homes made of mud and clay. In the winter this could be marginally tolerable but the summer climate regularly reached 95°F with occasional spikes closer to 105°F; when this happened, the habitat began to thaw, resulting in an intolerable stench.

Reb Leivik and Rav Pevzner alighted from the train. It was in the middle of the night and the streets were empty. It was cold and a harsh rain fell; given their weak physical state, remaining outdoors could be fatal. They began knocking on doors, hoping to find a Jewish home. They finally found a home with a dim light on; they knocked and the homeowner allowed them inside. The following morning, Reb Leivik sent a telegram to Rebbetzin Chana. In it, he described his location and requested that she send his tallis, tefillin, and various seforim.

Upon receiving the telegram, Rebbetzin Chana immediately went about preparing a package with the requested items. It arrived some three weeks later. In one of her diary entries, she describes her husband’s response upon receiving it: “The excitement of finally being able to put on tefillin for the first time in almost a year was indescribable!”

And then Rebbetzin Chana began the preparations for her own journey to Kazakhstan so she could rejoin her husband in some state of normalcy. Several loyal chassidim provided whatever assistance they could to make the difficult journey as manageable as possible. She arrived toward the end of Adar of 1940.

Rebbetzin Chana noted that, although her husband now had seforim to bring him spiritual sustenance, he also wanted to write his own chiddushim. The problem was that the primitive town had no writing implements. But Rebbetzin Chana had not traveled so far only to give up.

Approximately one week after Pesach, she travelled to a nearby town called Kyzylorda, where she purchased an assortment of herbs. She taught herself how to mix these herbs to ultimately produce ink and she then presented this concoction to her husband.

In her diary she writes: “The excitement he had upon receiving ink was indescribable. The joy of receiving writing implements brought him more joy than when he received a piece of bread after long months of hunger!”

Watering the Kazakh Wilderness

In a way, there was a silver lining to Reb Leivik’s exile sentence. As time passed, the Russians exiled more Jews to Kazakhstan and soon, a bona fide community began to grow — despite the miserable conditions. Reb Leivik was perfectly placed to serve as their spiritual leader.

Word of the learned rav in Shieli began to spread to nearby towns and Jews in outlying areas traveled there, just to be able to be in his presence and help him in any way that they could.

Deep in his remote Asian exile, far from any established centers of religious life and learning, Reb Leivik’s day-to-day routine soon became that of a conventional European rav: He taught the less learned, assisted those in need, and oversaw burials when necessary.

Tishrei approached. Rebbetzin Chana describes in detail how a minyan was arranged for Yamim Noraim and all the necessary roles — including chazzan, baal korei, and baal tokeia — were filled. She writes that the attendees were of divergent ages and backgrounds, some knowing little about Judaism. In the most primitive environs of Shieli, Kazakhstan, a group of Jews gathered around their sagacious rav in fervent tefillah.

Rebbetzin Chana describes the sublime joy of Simchas Torah and how her husband presided over a spirited farbrengen, just as he had back home.

Throughout this time Reb Leivik kept up a regular communication with his son, Rav Menachem Mendel — soon to become “the Rebbe” — who had emigrated to America in 1941. In one letter, the Rebbe wrote, “I shall never forgive myself for immigrating from the Soviet Union and leaving you behind.”

Reb Leivik’s sentence was officially a five-year exile, but since he promoted religion in defiance of Bolshevik principles, he was considered a “counterrevolutionary” and therefore an undesirable element. There would be no returning to Yekaterinoslav.

In any case, the arduous journey would be inadvisable, if not deadly. During his time in Shieli, Reb Leivik had grown increasingly weaker and, as the five years drew to a close, was clearly unwell.

Some 600 miles east of Shieli was a city called Alma-Ata (currently Almaty, the largest city in Kazakhstan). The Jews of Alma-Ata understood that Reb Leivik’s health was waning. They felt that he would benefit from the more spacious and accommodating environs of a larger city and so they began working tirelessly to obtain the required permits to allow such a move.

Rabbi Leibel Raskin a”h, who would later serve as the shaliach to Morocco, was a child living in Alma-Ata at the time. In an interview with the Derher publication, he described two local brothers, Hirshel and Mendel Rabinovitch, who were incredibly devoted to Reb Leivik.

Mendel, who had previously served in the military, made all the arrangements for Reb Leivik and Rebbetzin Chana’s move. Rabbi Raskin recalled how he went together with his family and the families of fellow chassidim to the train station to greet the Schneersons when they arrived.

The community rented an apartment for the Rav and Rebbetzin and, here too, Reb Leivik took on an unofficial role of spiritual leader. He delivered hours-long maamarim, which Rabbi Raskin said that he, as a child, could not understand.

But there was one occasion when he did understand. “It was Shavuos and Reb Leivik spoke about Matan Torah. He was mainly speaking to us children, and he emphasized how we must be fearless in our avodas Hashem, and not allow ourselves to be intimidated by the government.”

In a way, this was his parting message; immediately following Shavuos, Reb Leivik’s condition took a sharp downturn. The community petitioned a prominent professor who worked in the military hospital in Leningrad to make the trip to Alma-Ata to examine him. After much petitioning, the professor ultimately consented. He arrived and conducted a thorough examination.

The prognosis he shared was a grim one: Reb Leivik, it seemed, did not have much time left in This World.

Encased in Sanctity

The community coalesced around Reb Leivik, doing what they could to help ease his pain and hold on to the elevated soul that had suffered too much.

On Tuesday night, the 20th of Av, 1944, Reb Leivik asked for some water to wash his hands. “It is time to prepare for the journey to the other side,” he said. This was his last communication, but Hirschel Rabinowitz, who was at his bedside, noted that his lips continued to move. Leaning close, he heard Reb Leivik quoting the pasuk in Tehillim (77:20) “v’ikvosecha lo noda’u — and Your footsteps are not known.” And then he said, “Ay, ikvesa d’meshicha… ikvesa d’meshicha….”

His condition grew more critical as the following day progressed. Evening approached; the sun began fading from view.

And Reb Levi Yitzchak ben Boruch Shneur slipped away, finally able to dwell in the Heavens to which he forever aspired.

An announcement was made that anyone who wished to handle the meis would need to immerse in a mikveh. There was no mikveh in Alma-Ata; the closest option was some distance away, where a small reserve of rainwater had somehow survived the summer heat. Scores of men traveled there — no one wanted to miss the opportunity to pay their final respects to their beloved rav.

Rabbi Leibel Raskin recalled how his father had purchased six plots in the local cemetery to serve as Reb Leivik’s burial place, and later, purchased a significant amount of metal to erect a respectable ohel.

Volunteers dismantled the wooden chest that held Reb Leivik’s seforim during his sojourn in Kazakhstan and the table upon which he wrote his chiddushim, and restructured the wood to form a coffin. Reb Leivik would be laid to rest encased in the sanctity that defined his life.

The Rebbetzin stood back and observed as the crowds — many from neighboring towns — filled their home. She remained composed, reserved. But just as the levayah was about to begin she let out an anguished cry. “Groise mensch! Mit vemen hust du mir ibbergeluzt?! — Great man! With whom have you left me?!”

The journey from Reb Leivik’s home to the cemetery was a long and difficult one, as the roads were narrow, winding, and unpaved, but the throngs walked slowly, dutifully.

It was their final chance to connect with the fiery soul that had brough them the warmth of Torah, and incinerated any opposing influence.

IN

an almost uncanny way, Reb Leivik’s role within Kazakhstan set the paradigm for the movement his son would soon spearhead. Long before his beloved son would dispatch an army of soldiers across the globe to irrigate the spiritual wilderness with Torah and mitzvos, Reb Leivik created the template for this daunting yet fulfilling role.

A Hidden Hand plucked him from the pulsing heartbeat of Russian Jewish life and placed him in a remote town, isolated from any Jewish metropolis and infrastructure. Rather than despair or retreat, he drew on his inner reservoirs of spirituality and spread them to the masses. He taught, encouraged, and stood as a role model for so many Yidden who felt distant, disheartened, beleaguered.

Reb Leivik was the quintessential shaliach, long before his son coined the term.

In the remote Kazakh city of Almaty, in the foothills of the Trans-Ili Alatau mountains, lays a tzaddik whose light overpowers even the darkest shade. —

The Light Behind the Shade

I would like to make a wish that I will see publication of the letters of my husband, of blessed memory, which still remain. Something should be published from such a person, such a “maayan hanoveia” (overflowing wellspring) of Torah, never ceasing even for a moment…. Certainly, I am entitled to hope for this, after all that I have witnessed in my life… I cannot do anything to make it happen, but my desire for it is strong and I hope it will happen.

In this diary entry, Rebbetzin Chana expressed her fervent desire to see the publishing of her husband’s Torah while acknowledging that facilitation of such was beyond her reach.

In the summer of 1946, she began the process of leaving Russia, crossing the Russian-Polish border and journeying as far as Krakow. With her were three volumes of Zohar jammed with her husband’s comments. But Rebbetzin Chana was aware that attempting to cross the border with these seforim posed a very real danger. The name “Schneerson” was immediately associated with criminality in Russia; she herself was traveling under a pseudonym. She could not risk taking the seforim, which were stamped with the name “Schneerson.” At a loss, Rebbetzin Chana left the seforim in the care of a man named Reb Bentzion Kluvgant.

She arrived in America in 1947 and started a new life in the care and company of her son and daughter-in-law. Sometime in the year 1958, she was visited by a chassid named Reb Pinya Althaus who hailed from Nikolayev, Rebbetzin Chana’s hometown. Rebbetzin Chana shared how she had left the seforim behind and how worried she was about them. Reb Pinya assured her that he would do all that he could to locate them.

In 1959, he learned of a man named Reb Moshe Shub who was traveling to Moscow, and asked him to locate Bentzion Kluvgant and retrieve the seforim. Later, Reb Pinya wrote a letter describing Reb Moshe’s experiences: “He met up with Reb Bentzion. He asked him about the seforim. Reb Bentzion didn’t say anything. His faced changed colors and he retreated.”

But the following day, Reb Bentzion approached Reb Moshe and, in a whisper, told him where the seforim could be found. Reb Moshe retrieved them, but feared taking them across the border. Instead, he left the precious books with the Israeli Consulate, who could safely ship them to Israel.

(The Israeli government transferred the seforim to Reb Pinya, but only after a fight; they originally claimed the seforim as Israeli property.) In 1960, Reb Pinya presented them to the Rebbe.

Reb Leivik’s Sefer HaTanya, whose margins were also filled with comments, made its way to America the same year, thanks to the devoted efforts of a chassid named Reb Moshe Katzenelenbogen.

For some reason, the Rebbe kept these manuscripts in his private possession for nine years. Only after those years did he allow for the publication of four volumes of Likkutei Levi Yitzchak and one volume of Toras Levi Yitzchak.

But even once published, they were scarcely accessible. Reb Leivik’s Torah is extremely lofty, and, given his limited resources, was written with extreme terseness.

Rabbi Dovid Dubov, director of Chabad of Mercer County in Princeton, New Jersey, made it his mission to introduce Reb Leivik’s Torah to the world. Approximately 20 years ago, he began decrypting the many terms and expressions and providing the necessary commentaries to explain the latent intentions. He then divided the plethora of insights into sections based on the parshah, producing six volumes that run from Bereishis through Pekudei. He also published a sefer containing the many correspondences between Reb Leivik and the Rebbe, as well as a sefer on Megillas Esther and Purim.

As a result of Rabbi Dubov’s dedicated work, Reb Leivik’s Torah is now within reach for those accustomed to the terminologies of Toras Chabad.

F

urther access was granted to the masses some five years ago when Reb Michoel Goldman, shaliach to Kauai, Hawaii, and then editor in chief of Chabad’s Chayenu magazine, arranged for excerpts of Reb Leivik’s Torah to be translated into English. This was then disseminated to Chayenu’s readership of some 30,000. The enthusiastic feedback prompted Rabbi Goldman to collect these translated pieces and compile them into a sefer in honor of Reb Leivik’s 80th yahrtzeit, this past summer.

A story of mind-blowing Hashgachah pratis serves as the background of this publication. A group of devotees had dedicated themselves to the cause of compiling the sefer. At a meeting to discuss funding, one participant mentioned the name of a generous patron named Levi Yitzchak, who was passionate about spreading the Torah of his namesake, Reb Leivik. The problem was that he did not have the fellow’s contact information. But the name sparked a memory.

“I know that name!” Rabbi Goldman exclaimed. “We were in yeshivah together in Brunoy, France thirty years ago! I don’t have his number but I’m sure I can find it.”

The meeting adjourned and Rabbi Goldman returned to his job as a shaliach, which happened to present a rare opportunity that day. He was scheduled to fly to Hilo, Hawaii, an island some two hundred miles from his home base in Kauai, where a young shaliach needed help doing a kevurah the following morning. He arrived in Hilo and, at around 8:00 p.m. that evening, gathered the family of the deceased in the lounge of the Hilton Hotel so he could explain what a Jewish kevurah entailed. But there was a party in the hotel and it was hard to concentrate with all the noise, so he requested that they continue on the beach nearby. Once regathered, he resumed his talk.

“I was telling them about the concept of a minyan. I explained the significance of ten Jewish men together in one gathering. I told them that we had worked very hard to assemble a minyan and that we came up with nine men. We were short just one man and we would continue to pray that he be sent our way.”

Suddenly, he stopped short. There on the beach, he saw a man wearing a yarmulke and tzitzis walking along with his children.

“Actually,” he said, “we will have a minyan.” Then he turned to the group and said, “Watch a miracle unfold before your eyes.”

Rabbi Goldman beckoned to the man and asked if he’d be willing to join them for a minyan the following morning.

“What time?” the man asked.

“Ten o’clock,” Rabbi Goldman replied.

The man looked torn. “Uh… I think I can’t make it… I have a flight out tomorrow….” But then man’s eyes glinted with sudden determination. “You know what? I’ll be there! I’ll cancel my flight.”

“That’s wonderful!” Rabbi Goldman cried.

“Yes,” said the man. “Tell me, are you the shaliach here?”

“No,” Rabbi Goldman replied. “I’m just helping out for the day. I’m the shaliach in Kauai.”

“The shaliach in Kauai?” the man repeated. “My friend from many years ago is the shaliach in Kauai. Michoel Goldman — is that you?”

“It is,” said Rabbi Goldman. “And are you… Levi Yitzchak?!”

“I am.”

“But… what are you doing here?!”

“Well,” Levi Yitzchak explained, “I came here on a two-week vacation with my family, to a nearby hotel. Tonight is our last night. But suddenly, we saw some cockroaches in our room. Our children were terrified of them so we decided to switch to the Hilton. But my children were still disturbed by the cockroach incident so I took them out to the beach to calm them down.”

A stunned Rabbi Goldman told Levi Yitzchak that his name was raised that very morning as a potential donor for the new project. Realizing the tremendous Hashgachah pratis, the two agreed to meet later in the hotel, and Rabbi Goldman asked his new-old friend if he’d be willing to cover the publishing costs of the new sefer, set to be released in honor of Reb Leivik’s 80th yahrtzeit.

Yes, said Levi Yitzchak, he would most certainly be interested.

Later that night Rabbi Goldman was serving as the shomer of the meis when his phone buzzed. He looked at the screen — it was a picture sent by the Chabad shaliach in Almaty, Kazakhstan. The picture depicted a neatly organized set of booklets that Rabbi Goldman had printed the year prior, containing excerpts of Reb Leivik’s Torah. The booklets were meant for a group of Yidden visiting Almaty from New York.

“Why are people coming now?” Rabbi Goldman asked. “What’s the occasion?”

“It’s Tu B’Shevat tonight,” the shaliach responded. “The day that Reb Leivik arrived in Alma-Ata.”

Perhaps not in her lifetime, Rebbetzin Chana’s wish had come true. Her husband’s Torah is being printed, explained, simplified, and disseminated. With each passing year, interest in Reb Leivik’s Torah seems to grow, as do the crowds converging on his kever.

Someone once asked the Lubavitcher Rebbe if we can still witness miracles today. “Yes,” the Rebbe said. “I can tell you three.” Of the three, one of them was “that my father’s Torah made it to America.”

And that miracle keeps growing, each and every day.

With special thanks to Kehot Publication Society for allowing use of their translations of Rebbetzin Chana’s diary. Additional thanks goes to the Derher magazine whose research was critical to this article’s formation and to Rabbi Michoel Goldman, shalich to Chabad of Kauai, Hawaii for his guidance and assistance in this project.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1041)

Oops! We could not locate your form.