Trump Cards: Left Foot Forward

As Democrats descend into infighting, will the party wake up to the fact that its leftward lurch is toxic?

Photos: AP Images

As Democrats descend into infighting, will the party wake up to the fact that its leftward lurch is toxic? And can Republicans translate the second Trump victory into long-term power?

L

ike a combination of relay race and kindergarten circle time, the best way to picture the blame game underway in the Democratic Party is a loop. Kamala’s people blame Biden for arrogantly delaying his exit; Bidenworld is briefing against Obama for pushing the aging president out; and Obama insiders are heaping off-the-record scorn on Harris for the party’s humiliation.

The knives are out among Democrats — along with forks, spoons, and any other implement with which they can get at each other as the left melts down. Expect lots of performative outrage like Harvard’s tragicomic lecture cancellations for students left “feeling blue” by Trump’s victory. There will be many voices blaming the irreparable racism of more than that half the electorate. The machinery of the Democratic media-political industrial complex will gear up to “resist fascism” and manufacture a sense of perma-crisis in the Trump White House — a playbook that worked last time around.

But away from the tantrums, a serious debate is beginning to emerge to answer the question worth more than the billion dollars that donors poured into Kamala Harris’s campaign.

How, oh how — Democrats are asking — did a majority of voters reject the party of progress in favor of the dastardly Trump?

It’s the most important question that a defeated political party can ask itself — and also the question whose answer they are most likely to get wrong. Predictably, there are early signs that many are ignoring the clear wake-up call that Trump’s victory sends about what ordinary Americans want.

President Obama, for one, is intent on seeing the results purely as an aftershock of Covid, blaming “price hikes resulting from the pandemic,” “rapid change,” and “headwinds for democratic incumbents around the world,” in a post-election statement. In this analysis, there’s nary a word about the woke identity mania and anti-Israel demagoguery that have overwhelmed the party; no rebuke to the Democratic obsession with marginal cultural issues over improving the low wages and bleak outlook of many ordinary Americans.

One Democrat, though, has a theory about Harris’s trouncing that doesn’t involve whining. In his post-election diagnosis, Ruy Teixeira, a storied Democratic strategist, pointed the finger at the party’s leftward lurch.

“The Democratic Party may be the party of blue America, especially deep blue metro America, but its bid to be the party of the ordinary American, the common man and woman, is falling short,” he wrote. “There is a simple — and painful — reason for this. The Democrats really are no longer the party of the common man and woman. The priorities and values that dominate the party today are instead those of educated, liberal America.”

Given his role as longtime Democratic seer, Teixeira’s broadside will stoke an anguished debate inside the Democratic Party — one that the triumphant Republicans need to watch if they hope to turn Trump’s second victory into long-term power.

In that debate, a half-century-old political specter will be resurrected: that of George McGovern, whose 1972 loss has haunted the Democratic Party ever since. It will be fought over to explain whether the party can safely double down on the progressive present — as Obama implies — or needs to abandon wokery and course-correct for the center in order to recapture the White House in 2028.

History Lessons

G

eorge McGovern’s failed 1972 campaign — which foreshadowed today’s era of identity politics — is the ABC of Democratic Party history. The South Dakotan senator began his long-shot campaign with an insight: that there was a realignment underway in American politics. Southern states — hitherto Democratic strongholds — were turning red. To win, Democrats would need to assemble a new coalition. It would focus heavily on “identity” causes such as African-American, women’s rights, and liberals opposed to the Vietnam War. This would be combined with a populist economic message to target working-class whites.

McGovern’s coalition was like a mash-up of the modern Democratic and Trumpian Republican parties, marrying the identity politics of the former with the working-class populism of the latter.

The combination, said Josh Mound in a 2017 New Republic essay, was enough to unnerve Republican incumbent Richard Nixon, but in the end, McGovern’s campaign fell apart under the twin blows of its own ineptitude and attacks from moderate Democrats.

“Anti-McGovern Democrats staged an ‘Anybody but McGovern’ movement at the convention,” Mound wrote. “When that failed, some pledged that they would not campaign for him and might even support Nixon.”

The result was a wipeout for the ages. Richard Nixon trounced McGovern by 23 points in the popular vote, and the Democratic Party was changed forever. The lesson that Democrats drew from the debacle, says Mound, was “McGovernism” — a fear of all things left-wing. The party’s center of gravity lurched rightward as Democrats became more hawkish on defense and focused on the free market and not economic inequality. As late as 2012, when Obama ran for a second term with a hint of economic populism to contrast himself with Mitt Romney’s corporate image, McGovernism was invoked by Democrats fearful of deviating from the center.

That, the Democratic left has long contended, was the wrong lesson to draw. McGovern wasn’t wrong, they say — no Democrat could have won the 1972 election given Nixon’s popularity and the booming economy.

Nixon shifted to the left by instituting wage-price controls to clamp down on inflation and promised to cut taxes on the working class if reelected. Thus, the entire genesis of neoliberalism — the decades-long rightward tilt that was the reaction to McGovern’s faceplant — was misbegotten, critics say.

By way of evidence, they point to the other side of the aisle and the lesson of Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. The Arizona-born senator and former Air Force general was in some ways a political twin of McGovern’s. Goldwater’s 1964 trouncing at the hands of Democrat Lyndon Johnson was by a similar astounding margin — 22 points. Like McGovern, he had run on his party’s flank trying to replace the moderate Republicanism of the day with something that we’d recognize as Reaganite conservatism.

Goldwater advocated hawkish confrontation with the Soviets, opposed the unions, was leery of the welfare state, and proposed tax cuts for the rich to boost the economy. His resounding defeat was the end of Barry Goldwater’s presidential aspirations, but his ideals found their way into the Oval Office within 15 years of his defeat. Unlike George McGovern, Barry Goldwater lost the battle of the ballot box, but went on to win the battle of ideas.

Revenge of the Left

B

ut did McGovern really fail? Like many a failed pioneer, George McGovern’s central premise may not have been wrong; he was simply a few decades ahead of his time.

In 2002, two political scientists, Ruy Teixeira and John Judis, wrote a book that made Democratic hearts thrill. The Emerging Democratic Majority contended that America’s shifting demographics were giving rise to a strong new Democratic voting base comprised of minorities, college-educated liberals, and working and single women. Teixeira and Judis called this new constellation “George McGovern’s Revenge” because it represented the triumph of McGovern’s vision.

That theory didn’t alter facts on the ground in the Bush years, but when Barack Obama swept into power in 2008, the Democratic majority had — it seemed — finally emerged. Obama’s victory was built on maximizing turnout among minorities, taking 79 percent of the non-white vote; making a breakthrough among white college-educated voters to carry this demographic by one percent; and stemming the party’s long-term deficit among white working-class voters.

Even after the bloodbath that was the 2010 midterms, when Democrats lost 63 seats in the House, Obama’s personal popularity and savvy campaigning delivered a second term. That was based on minorities growing by two percent as a share of the vote, Obama’s dominance of the professional and women’s vote — and crucially, a 23-point lead among young voters.

As Barack Obama gave his second inauguration address, it seemed that the American future would be Democratic blue, from sea to shining sea. Teixeira was able to write, with some justification “We are now ten years farther down this road and McGovern’s revenge only seems sweeter.”

And then it all fell apart.

Workers of the World

D

onald Trump’s 2016 victory was a profound shock to the system worldwide. From European chancelleries to NATO headquarters and Gulf palaces, leaders scrambled to fathom what madness had gripped the American electorate. Hillary Clinton had seemed a shoo-in against the “basket of deplorables” headed by Deplorable No. 1.

Trump’s victory, says Teixeira, was based on a profound Democratic misreading of Obama’s 2012 win. Excited by their coalition of minorities and progressives, Democrats had ignored the contribution that white working-class voters had made to Obama’s success. And so when Trump won the GOP nomination, Democrats were elated, believing the New York celebrity mogul to be unelectable given his anti-immigration stances. They sneered at his numerous vocal supporters as vulgar racists.

Reliant on misleading polls, Democrats missed the dramatic swing in the working-class vote. In 2016, Trump hiked the Republican lead among white working-class voters six points, to a yawning 31-point gap.

But their loss didn’t act to sober Democrats. Instead, they caught a severe case of Trump Derangement Syndrome — and entirely missed the lesson that his rise should have taught. In a recent essay, “Politics Without Winners,” Teixeira and political scientist Yuval Levin note that the left’s interpretation of Trump’s victory as being linked to a racist backlash against a black president had far-reaching implications for their overall worldview.

“It encouraged the Democratic Party’s burgeoning cultural left to build on that interpretation and link it to their radical critique of American society as structurally racist, hostile to all ‘marginalized’ communities, and embedded within a rapacious capitalism that would destroy the planet.

“This view spread through sympathetic cultural milieus where it already had a considerable presence: universities, media, the arts, nonprofits, advocacy groups, foundations, and the Democratic Party’s infrastructure. In those spaces, progressivism became redefined to include that radical critique and the necessary link to all associated issues.”

Thus, the Democratic Party of the Trump-Biden era became associated with radical-left identity campaigns like Black Lives Matter, and the related calls to defund the police; wide open border policies that aided the entry of vast numbers of illegal immigrants; the eye-wateringly expensive Green New Deal; and a focus on radical gender policies.

In effect, Democrats had ceded the working-class-friendly plank of McGovern’s program to Donald Trump, and were left with only the identity politics.

Voters noticed, and they didn’t like it at all. They snatched control of the House from the Democrats in the 2022 midterms, pulling the lever for Republicans even as the GOP doubled down on the Trumpiest of Trumpian candidates.

Wake Up or Double Down?

W

ith Democrats in trouble in the late Biden era, Ruy Teixeira and John Judis set out to explain how the leftward march had imperiled the party. Published in 2023, Where Have All the Democrats Gone? argued that Democrats had shot themselves in both feet: by embracing identity politics and driving working-class voters into the arms of Donald Trump by continuing to support elite-friendly economic policies.

The cultural radicalism of what they call the Democrats’ “shadow party” — comprised of the activists, think tanks, foundations, publications, big donors, and prestigious intellectuals that set the tone for the party — has endangered Democrats at all levels given how out-of-step the party is with mainstream American opinion.

“Democrats,” Teixeira and Judis write, “need to look in the mirror and examine the extent to which their own failures contributed to the rise of the most toxic tendencies on the right.”

Reflecting the deep historical roots of the current Democratic moment, the crux of that argument is what Joshua Mound would call classical McGovernism. It’s a call to swing to the center, on issues that are repelling working class voters such as race, immigration, and climate policy.

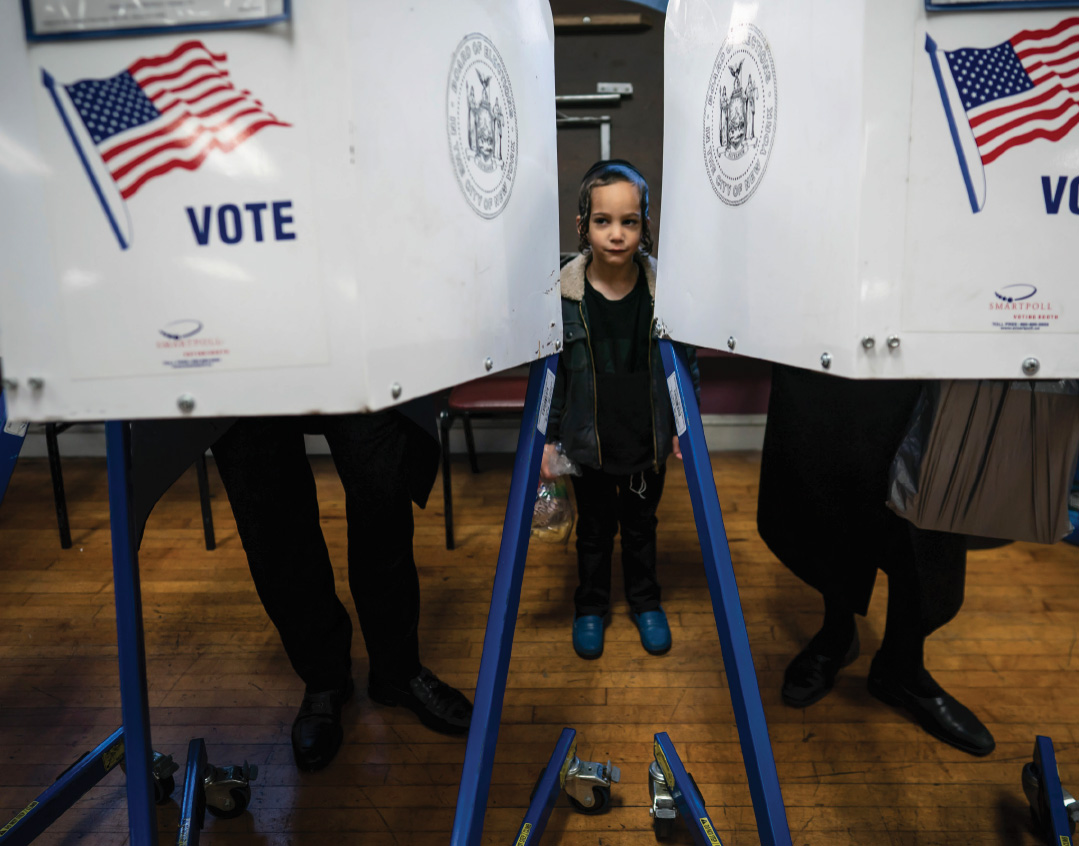

The test will be in the days ahead: Whoever now helms the party, are Democrats chastened enough to listen to Ruy Teixeira, the man who predicted their rise, and then foretold their defeat? Will defeat act as a wakeup call for a party that has now turned its back on the bedrock of its support in blue-collar America?

Republicans need to watch carefully for the results of that internal battle, because their own new working-class coalition may be more fragile than they assume. If Democrats head to the center and Trump struggles to deliver for them, they could head back to the left — a home to a surprising number of working-class voters as recently as 2012.

About the fragility of supposed realignments, and the fickleness of working-class voters who’ve soured on the left and drifted right, ask Trump’s first-term counterpart Boris Johnson, whose massive gains among Britain’s working class crumbled as he failed to deliver.

Post-election, there are signs that the Democrats are chastened by defeat. Commentators recently rah-rah for Harris are now lasering in on the “identitarianism” (i.e., wokeness) of the party. The New York Times notes the difference between the social media reaction of 2016 and that of 2024. Eight years ago, “online platforms were awash in calls to protest the day after Donald J. Trump’s victory.” Now, it seems like “business as usual.”

But to judge by Joe Biden’s preelection dismissal of Trump’s supporters as “garbage,” the old “basket of deplorables” trope that paved the way for Donald Trump’s return is hardwired into the party’s thinking.

Lip-curling contempt for half of the electorate isn’t a great way to expand your voter base. It leaves open only one avenue for victory in 2028 for a party scarred by the memory of George McGovern: hoping that, long-term, voters find the MAGA movement as awful as Democrats preach that it is.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1036)

Oops! We could not locate your form.