A Great Name

| October 29, 2024Minsk enjoyed a rich history of Jewish life, yeshivos, and batei medrash, along with a slew of prominent rabbinical leaders

Title: A Great Name

Location: Minsk, Russian Empire

Document: Ha-Tsfira

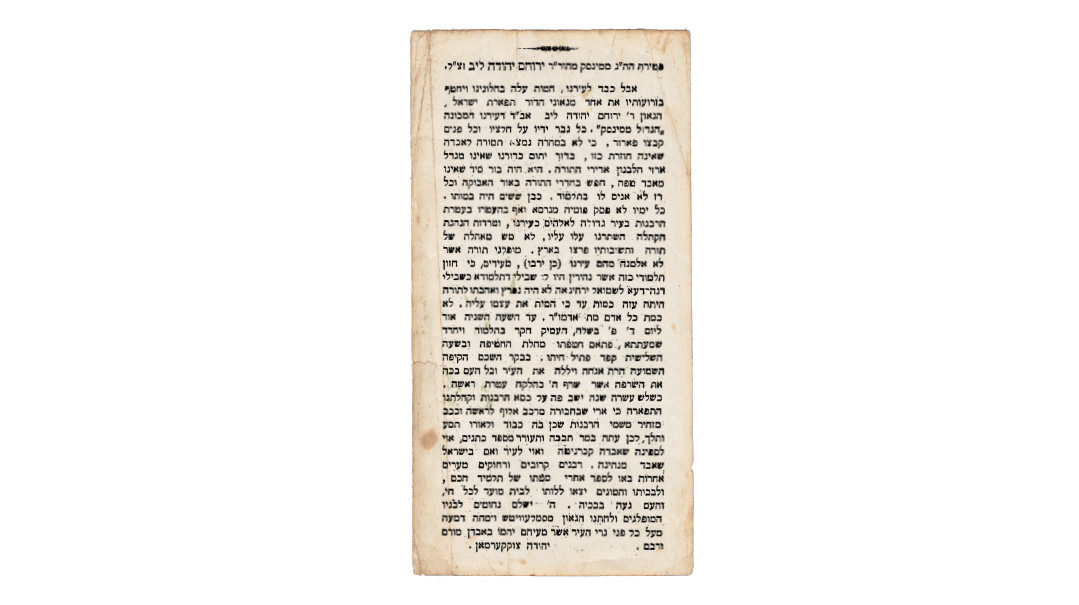

Time: January 1896

AS one of the largest and most prestigious communities in the Pale of Settlement, Minsk enjoyed a rich history of Jewish life, yeshivos, and batei medrash, along with a slew of prominent rabbinical leaders. When Rabbi Dovid Tevle (Rubin), the rav of Minsk, author of Nachlas Dovid, and a famed student of Rav Chaim of Volozhin, passed away in 1861, it was a challenge to find a suitable replacement for such an esteemed figure in one of the most important rabbinical positions in all of Russia.

In the interim, several figures served informally as community rabbi, among them the deceased’s son-in-law Rav Moshe Yehuda Leib Hindin, who until then had served as a dayan on the Minsk beis din. Only after 20 years, in 1882, was an official chief rabbi of Minsk finally installed: Rav Yerucham Yehuda Leib Perlman (1835–1896). One of the most outstanding Torah leaders of the late 19th century, he was to be known to posterity as the Minsker Gadol.

Yerucham Yehuda Leib Perlman, born into a modest home in Brisk, displayed exceptional brilliance even as a young teenager. It didn’t take long for Rav Yaakov Meir Padwa, renowned author of Mekor Mayim Chaim and rav of Brisk, to take notice of his sharp intellect and profound knowledge. Recognizing his potential, Rav Padwa guided the young prodigy, knowing that with the right direction, he could one day become a Torah giant.

Yerucham Leib married Rav Padwa’s daughter at just 13 and soon journeyed to Kovno. There, his genius caught the attention of Rav Yitzchok Avigdor, the rav of Kovno. So impressed was Rav Yitzchok Avigdor that he secured the support of a prominent lay leader, Rav Yaakov Moshe Karpas, who welcomed Yerucham Leib into his home, ensuring all his needs were met. Over the next two years, Yerucham Leib’s reputation as a Torah scholar spread throughout the region.

He began his rabbinic career in Seltso in 1863, followed by a distinguished 13-year tenure as rav of Pruzhany. In each role, he demonstrated his deep commitment to Torah, humility, and an uncompromising approach to halachah. In 1882, he was called upon to serve as the chief rabbi of Minsk, where he restored the city’s rabbinic authority to its former glory.

Various interpretations have been offered as to the origins of the honorific “Minsker Gadol,” which deviated from the standard titles of chief rabbi or mara d’asra. Rav Eliyahu David Rabinowitz-Teomim, the Aderes, recorded in his autobiography Seder Eliyahu two possible explanations for the Minsker Gadol’s title. As winds of change swept through the Pale during the closing decades of the 19th century, progressive elements within the Minsk Jewish communal leadership endeavored to appoint a more liberal rabbi. Conservatives demanded that a true gadol be appointed, as per the longstanding tradition of Minsk. When the side promoting the appointment of a gadol won out and Rav Perlman was duly hired, the victory was eternalized in his appellation; the Minsker Gadol was the rabbi, and not a more liberal appointee.

The Aderes submitted another rumor that the Minsker Gadol had actually chosen the moniker for himself. Until the early 19th century, all rabbis of Minsk had historically been referred to by the formal title of “rav of Minsk.” Upon the passing of Rav Yisrael Mirkis in 1813, this title was officially discontinued, and subsequent rabbis were recognized by the title “mara d’asra of Minsk,” which was considered a somewhat lesser designation. This was done because the Jewish community of Minsk owed a financial debt that obligated them not to appoint a “rav of Minsk” until it was paid. By renaming the official post “mara d’asra,” they could circumvent the obligation. According to this rumor, Rav Yerucham Yehuda Leib Perlman disliked the title mara d’asra, and asked to be called the Minsker Gadol.

A third reason is offered in the official biography of the Minsker Gadol written several years after his passing. One of the lay leaders of Minsk visited the new rabbi shortly after his appointment, and upon leaving, he remarked, “This is an adam gadol!” Somehow this nickname of “Gadol” stuck. The likely background for this story is the 22-year vacancy in the seat of the chief rabbi, with the long shadow of Rav Dovid Tevle, the Nachlas Dovid, hovering over Minsk. The Nachlas Dovid was one of the most famous and respected rabbis in the world, and the Minsk community was quite proud of his legacy. He was viewed by many as irreplaceable, and any successor would have to fill his large shoes.

When it became evident to the residents of Minsk just how great their new rabbi Rav Yerucham Yehuda Leib Perlman truly was, they were satisfied that he was a worthy successor to the great Nachlas Dovid. To highlight the new rabbi’s position, he was bestowed the title Minsker Gadol.

Mussar Pr(opponent)

While residing at the home of Rav Yaakov Moshe Karpas in Kovno, he often came into contact with the great founder of the Mussar movement, Rav Yisrael Salanter, who also received support from his host. While Rav Yerucham Leib initially rejected Mussar as unnecessary–as he believed that only pure Torah study could cure the generation’s woes, he eventually came to appreciate Rav Yisroel and his accomplishments. In The Minsker Gadol, the author describes the story of their departure:

When Rav Yerucham Leib resolved to leave Kovno, he went to see Rav Yisrael Salanter to pay his respects.

“Rebbi, bless me,” he requested.

In response, the founder of the Mussar movement replied, “I am not your rebbi, for we are distinct from one another both in nature and ideology. I deal with the broad public, and, as a result, I cannot always deal with individuals. But I see that you have no desire to concern yourself with communal matters, and you concentrate on the individual with the aim of perfecting your own soul.

“My prayer for myself is that my communal spirit not overwhelm my concern for the individual, and for you I pray that your spirit of individualism will lead you to such perfection and brilliance that you will be able to serve as a shining example and role model for the general community.

“As you well know, the Torah is interpreted on occasion by reference to the principle of klal and prat, a general rule followed by a detail to explain it; on occasion, the general rule is dependent on the detail, and sometimes the detail is dependent on the general rule to appreciate the principle involved. So, in fact, there is no major distinction between us. Each of us should pursue his path in accordance with his talents and wisdom, so long as neither departs from the course he has set for himself. And now, Rav Yerucham Leib, I ask you to give me a blessing.”

The young man responded by citing the well-known Talmudic saying (Taanis 5b), “Tree, tree, with what can I bless you?”

“If I bless you that you should have Torah and wisdom — behold, these you already possess in abundance. And if I bless you that you should have mussar and upright traits, behold, you are the master of these virtues. And if I bless you that you have riches and honor, behold, you abjure these things and despise them intensely. So instead, I bless you that your students shall be like you, that they not be marked with jealousy or hatred of any person, and that you never be embarrassed or disgraced by them either in this world or the World to Come.”

Upon hearing these words, Rav Yisrael sighed deeply and kissed him goodbye.

Great Progeny

The Minsker Gadol had a large family, with many descendants serving in prominent diverse roles in subsequent generations. One of his sons-in-law was the last rabbi of Kovno, Rav Avraham Dov Ber Kahana-Shapiro, the Devar Avraham. The Minsker Gadol was succeeded in the Minsk rabbinate by another son-in-law, Rav Eliezer Rabinowitz, who served in that capacity until his passing in 1924.

A prominent public leader of Russian Jewry, Rav Eliezer Rabinowitz represented the Russian rabbinate at various conferences, including the Bad Homburg conference of 1909, which led to the establishment of Agudas Yisrael, and the 1910 rabbinical conference in St. Petersburg. During World War I, he personally assumed responsibility for the throngs of refugees streaming into Minsk due to the advancing front. He continued to serve as rabbi of Minsk during the Bolshevik Revolution and the early years of the Soviet Union.

Rav Eliezer Rabinowitz was succeeded by his son-in-law Rav Menachem Mendel Gluskin. Despite his conviction in a show trial by the Yevsektsia and subsequent arrest by the NKVD, he served as the rabbi of Minsk through the darkest years of the Communist era. Following his banishment from his home, he relocated to Leningrad, where he served as a largely underground rabbi until his passing in 1936.

This article was published in conjunction with the recent release of the English biographical work titled The Minsker Gadol (Feldheim). Based on an original biography written by his close associate, Reb Meir Halpern, in 1913, it has now been translated into English for the first time by the Minsker Gadol’s descendant, Rabbi Shlomo Slonim. The research of Reb Nosson Kamenetsky was also integral in preparing this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1034)

Oops! We could not locate your form.