The Brother I Never Knew: Soul Sisters

| October 13, 2024So much more binds us than separates

In the wake of the tragic events of October 7, unlikely yet remarkable human connections have emerged out of shared purpose and resilience. Through their collaboration, they developed new perspectives and understanding of the other’s world, and achieved something greater than themselves, as they learned to see beyond differences, bridging divides that once seemed insurmountable. Here are their stories.

Shelly Shem-tov never had a chareidi friend, and Margalit Peretz rarely interacted with secular Jews. But when Shelly’s son Omer was kidnapped, Margalit’s family adopted him as their very own.

“Find me that woman from the video!” Tzili Schneider, founder of the Kesher Yehudi kiruv and unity organization, charged project director Margalit Peretz.

“That woman” she was referring to was the one decrying the divisiveness and politics surrounding the hostages, screaming for unity as the only way to bring her son Omer and the others home, in a powerful clip gone viral. And it didn’t take long for Margalit to do just that.

“I just put on my status that I was looking for her and I got the number right away,” Margalit remembers.

“Get me that crazy lady’s number,” jokes Shelly Shem-Tov — “That woman.”

“No, not crazy, no one said that,” Margalit, seated next to Shelly, shoots back.

The two of them are in the lobby of the David Citadel Hotel, just outside Jerusalem’s Old City, an unlikely pair if ever there was one. Their camaraderie is as natural as that of sisters, and it’s hard to believe they met less than a year ago.

Long before Simchas Torah, Shelly Shem-Tov, 52, was a passionate advocate for connection. A freelance interior designer and relationship mentor from Herzliya, she describes herself as a “typical chiloni (secular) woman. I light Shabbat candles and we eat a family meal Friday night, but we never kept Shabbat. We’re not religious.”

Shelly and her husband Malki have been married for 30 years (yes, that’s his name — as in “my king.” “His father anointed him the day he was born,” Shelly says with a laugh). They have three children: Donna 28, Amit 25, and Omer — the son we’ve come to know on our davening lists as Omer ben Shelly — soon to turn 22. (Please G-d, in freedom.)

Margalit Peretz, 30, is as typical a representation of her own chareidi demographic as Shelly is of her chiloni one. She grew up in Har Nof, went to Bais Yaakov schools her whole life, married an avreich learning full time in kollel, and is now a mother to three young children.

“I made two or three secular friends over the years, and that might have made me somewhat more open-minded, but for the most part, I’ve lived an insular, sheltered, typical chareidi lifestyle,” Margalit reflects. “I had zero connection to the kiruv world until I started working at Kesher Yehudi four years ago.”

Kesher Yehudi, a unity project that pairs secular Jews interested in learning with an observant chavrusa, was the extent of Margalit’s connection to the secular world — until Tzili asked her to track Shelly down.

IN

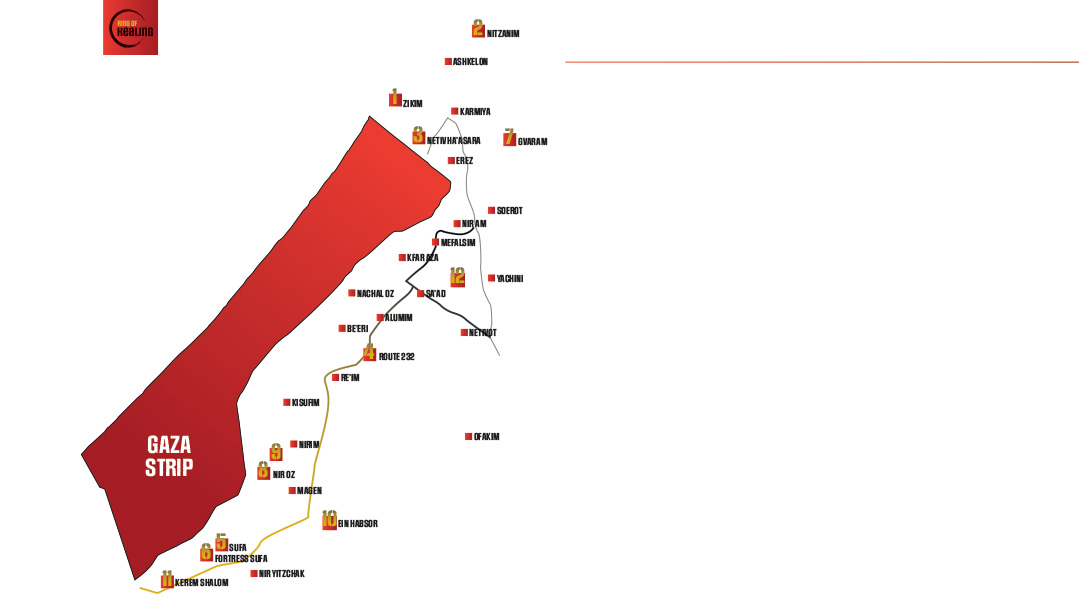

those early days when her world turned upside down, there was no way Shelly could have known she was about to set a whole lot of things straight for the rest of us. While many families had to wait days, or even months, to learn the whereabouts of their loved ones, already on October 7, the Shem-Tovs saw a clip of Omer being abducted from the Nova festival and taken across the border to Gaza.

The Shem-Tovs were overwhelmed with fear and dread. The country was in turmoil.

Then Shelly heard about a man who had gone to sit in the Kirya, the area of the IDF’s headquarters in central Tel Aviv., right off Kaplan Street. His wife and two daughters had been kidnapped (they’ve since been released), and his house had been burned down.

“I was in a bad place — my Omer had been kidnapped — but this man’s situation was worse than mine, so I went to sit there with him to show my support,” Shelly recalls.

But when she got there, she was horrified by the scene: people shouting, demonstrating, taking the whole situation in a political direction.

“Even before October 7, it was hard for me — the demonstrations and counterdemonstrations and what happened on Yom Kippur when they didn’t let people daven. But seeing it there, I couldn’t handle it,” she says. “I went crazy. I started shouting, ‘We’re in the greatest pain now. This isn’t what we should be doing. We need to be together, we need to be unified.” ”

Next thing she knew, the video went viral.

F

or many in the Torah world, Shelly’s message was a wake-up call of sorts. Here was this woman who did not appear to have any connection to their world shouting truths that deeply resonated.

But in those first few weeks, the Shem-Tovs didn’t feel that chareidi support.

“Their voice was missing. Where are they? We’re in so much pain, and we’re not feeling that the chareidim are here with us. Their absence was felt very strongly,” Shelly remembers.

She met one chareidi woman and asked her where all the chareidim were.

They’re scared to come, they’re worried they’ll be sent away, she was told.

Shortly after, Kesher Yehudi arranged a Rosh Chodesh Shevat kennes in Binyanei Ha’umah for three thousand chareidi women. Shelly, the mother of a hostage, was slated to speak.

“I almost canceled.” Shelly confesses. “I was so exhausted. I had been speaking all over — in studios, for television, and at hafrashot challah events; there were non-stop hafrashot challah events all over. I called Tzili and told her I just couldn’t. But if you know Tzili” — here both women laugh — “she told me how much chizuk I would give everyone, how many women were waiting for me.”

At the gathering, Shelly sat next to Margalit. She then went on stage as part of a panel with a Nova survivor whose husband was killed there and a frum mother whose son was killed while working as a guard at Nova. Afterward, Margalit approached Shelly with a book of tefillos that her mother had compiled and insisted she give to all the mothers of the hostages.

Then Margalit shared one more tidbit: After October 7, in order to feel the pain of the hostages and their families and to daven for them as individuals, the Peretz family had “adopted” two hostages. One of those was Omer, and every Shabbos, they set him a place at their table. Shelly was incredibly moved to hear this.

“We had two hostages, and one was released after two weeks — and we’ve been stuck with Omer until now,” Margalit explains as they both laugh, before she turns serious. “Omer will come back, too.”

“Yes, Omer will come back,” Shelly agrees. Margalit asked Shelly if they could take a picture to show her children who Omer’s mother was, and the women exchanged numbers. When Margalit returned home, she told the kids to guess who she’d met at the kennes.

“I must’ve played Guess Who with them for an hour until they figured it out,” Margalit remembers. “They were so excited. They wanted to send her messages before they even went to gan the next morning: ‘We want to meet you. Omer will come home.’”

“When we make a mesibat hodayah when Omer comes home, you’ll come,” Shelly responded. (The Peretz children still talk about how they will go to Omer’s mesibat hodayah.)

Subsequently, Margalit sent Shelly pictures of Omer’s seat at their Shabbos table. Two weeks later, Shelly called Margalit.

“There’s an erev tefillah in the tent across from the Prime Minister’s residence. Can you come?” Margalit went, of course, and before they parted, Shelly gave her a picture of Omer so her children could see what he looks like and place the photo at his place at the table. Interestingly, Omer bears a striking resemblance to Margalit’s children.

“They could be his little siblings,” Shelly says, shrugging. “My neighbor said, ‘The moment I saw that hostage, I thought to myself he looks like one of Margalit’s,’ ” Margalit remembers.

M

eanwhile, Tzili heard about the hostage tent and the weekly tefillah and asked Margalit to take her there. On the spot, she decided that they had to arrange a Shabbos for the hostage families. She asked around and was told Shelly was the one to speak to.

Then she asked Margalit to arrange it. “I was so surprised Shelly agreed,” Margalit remembers.

Shelly shrugs, not quite sure she had actually agreed, but a week-and-a-half later, 40 families came to keep Shabbos at the Waldorf-Astoria in Jerusalem. In the hotel lobby, Margalit’s children saw Shelly and Malki wearing t-shirts with Omer’s picture and ran up to them.

“What is our Omer doing on your shirts?” “This is my Omer,” Shelly said, and the children instantly understood who she was.

The connection was magnetic; Margalit’s children were drawn to Shelly and she to them. “That whole Shabbos was connection on a different level,” Margalit says. “During the car ride home, my kids cried that they missed Shelly. I sent her a message, and she said, ‘I also miss them. I’ll have to come see them.’ I said to myself, okay, she’s polite and doesn’t want to insult us, but the very next day she called to say she was in the area and wanted to come visit. I was surprised, to say the least, and so happy.”

Shelly, who has kept Shabbos since that weekend, came to Margalit’s house with her oldest daughter Donna, who hadn’t been at the Shabbaton. Both families started meeting regularly, and the extended families have also become close.

“That was your mother,” Margalit tells Shelly with a laugh as she hangs up the phone in the middle of our interview, before explaining that she’s in touch with Shelly and Malki’s aunts and other relatives as well. “I need a family tree to keep track of everyone.”

The first Kesher Yehudi Shabbaton was followed by another at the David Citadel a month later, and then Krias Megillah, a Purim seudah, and a Pesach Seder.

The events all seem religious, but Margalit explains there’s no religious pressure.

“It was never about that,” she says. “Holidays are family time for everyone, and we wanted to be there for these families during the hardest times. Pesach is the festival of freedom. Leaving the slavery in Mitzrayim — how can families living that reality now face the chag like that? Families told me, ‘We’re going to stay in bed the whole time.’ So Kesher Yehudi arranged a Pesach Seder no one will ever forget.”

Shelly nods in agreement, and then turns pensive.

“Kesher Yehudi understood something long before last Simchat Torah, and it’s not self-evident by any means: There needs to be this connection between chareidim and chilonim. We have so much more in common than what separates us. That’s what happened between me and Margalit. I had no interaction with chareidim before I met her. If I look at her without knowing her, we have nothing in common — not the way we dress, not the way we look. I thought all religious people just wanted to make you do teshuvah.”

Margalit has also found these last few months eye-opening.

“I always attributed many stigmas to chilonim, especially left-wing chilonim. They were something totally distant.”

(The secular Jews she was in touch with through Kesher Yehudi had reached out to learn, so they were already closer to religion, she reasoned.)

“Davka, many of the hostage families are very left-wing, but even people who claim to be so far from religion have a very strong Jewish spark,” she says. “Don’t assume everyone who is different from you is totally wrong or is bad. We all stood at Har Sinai, and the Torah belongs to them as much as it belongs to me.”

Margalit recommends the weekly Tuesday tefillah at Kikar Hachatufim, Hostage Square, in Tel Aviv. The atmosphere is religious, not uncomfortable for chareidim, and every show of support there gives the hostage families so much koach.

Shelly ends with one additional request, that everyone should adopt one hostage.

“It makes your tefillot so much more powerful,” she says. “You’re focusing on one person, so they become real to you and that brings energy to the person you’re praying for.”

“There’s a place to mention all the hostages,” Margalit says. “When I light my candles and when I daven Shemoneh Esreh, I say every name. But Omer — Omer has a special place — at our Shabbos table and in the personal requests I make from morning until night. I feel a personal responsibility to bring him home, and it’s a shemirah for him.”

Shelly looks fondly at Margalit. “I have a picture that plays in my mind of the moment I will greet Omer,” Shelly says. “And I’m waiting for the moment Omer can meet his aunt.”

“Who knows what Shelly will be up to when Omer is freed?” Margalit says. “But I have a deal with her mother. The moment it happens, it doesn’t matter what time of day or night — she’s going to call me right away.”

Two women, united in their hopes and prayers for Omer, the son whose family pines for his safe return, the hostage who brought two women together — and sparked a revolution.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1033)

Oops! We could not locate your form.