The Little Teivah and the Foolish Shepherd

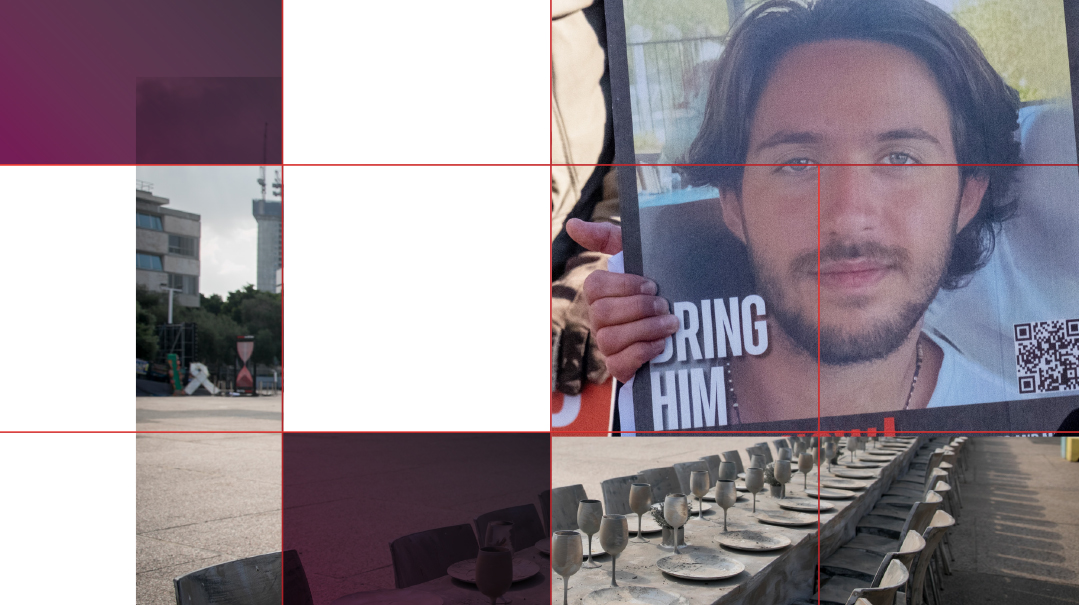

| October 13, 2024One year later, converging circles of heart and hope

Photos: AP Images

Noach stepped out of his teivah. Although he knew what to expect, the sight of it shook him to his core. A prosperous, blossoming, incredibly beautiful world was no more. People, animals, trees, and plants were gone. All that remained was muck and more endless muck — the residue of a verdant world utterly destroyed.

Noach could not contain himself, and turned to Hashem demanding, “You, Who are the Merciful One, how could You have done it?”

What did Hashem reply?

“Foolish shepherd, when I told you that you are the only righteous one, that I was going to bring a deluge upon the world and that you should build a teivah, what were you thinking? I warned you about the flood and delayed it for so long so that you would pray for the entire world. But as soon as you heard that you would be saved in the teivah, you didn’t even think of praying for anyone. You simply built the teivah and saved yourself. Now that the world has been destroyed, you are opening your mouth to talk to me about mercy? Why did you not pray then?”

Noach then became contrite and then began offering sacrifices.

Zohar 1, 67b

T

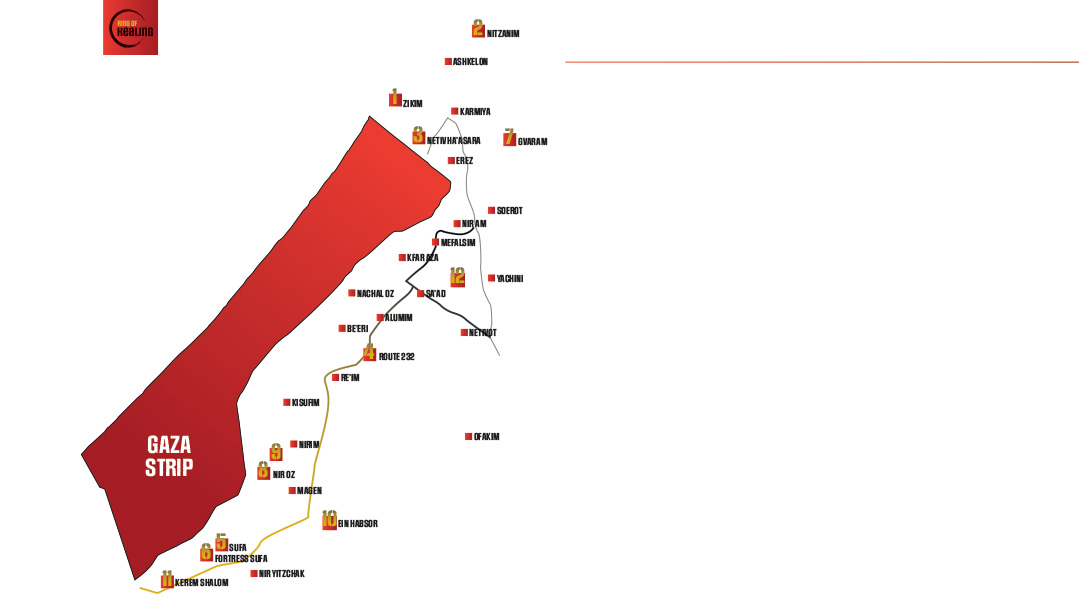

he events of Simchas Torah 5784 were a churban. It was not about any one person being killed, or even many people. It was wholesale destruction. A whole swath of Eretz Yisrael was overrun by those bent on destroying us. And they actually succeeded in doing so, to a certain degree. Entire communities and villages were wiped out. Fields and orchards, homes and belongings, women and the elderly and infirm, all were ravaged and pillaged.

We woke up the day after Simchas Torah to a post-mabul world. No one who saw the churban, including non-Jews, remained dispassionate. As humans, we are programmed to crave living, thriving, and blossoming; churban is the antithesis of all of that.

As we look around at the devastation, we raise up our eyes to Heaven, and in our hearts, Noach’s question wells up: “How could You, the Merciful One, bring such destruction to Your beautiful world?”

But we are maaminim. We know Hashem has a plan. Having learned the parshiyos of Bechukosai and Ki Savo many, many times, we know that our relationship with Hashem is a two-way covenant. We are His chosen people, and if we choose to stray, chas v’shalom, we suffer the terrible consequences listed in the tochachah.

The devastation spelled out in these perakim is so ferocious that we read it quickly and quietly, for it is painful even to think about it. Since the destruction that happened on Simchas Torah echoes so much of that tochachah, we could easily conclude that the wrongdoers among us are at fault. As further evidence, witness the almost miraculous sparing of the various shomer Shabbos communities in the Gaza Envelope region. What further proof do we need?

But if these are our thoughts, then Hashem turns to us and pounds us:

“Foolish shepherds, where have you been? If you are indeed the ‘righteous ones’ and the knowers of the truth, what have you accomplished with your knowledge? If a few thousand people gathered to be mechallel Yom Tov for a placebo spiritual buzz, why didn’t anyone get to them and somehow draw them to the real joy of Simchas Torah? Included in that crowd were a few hundred kids who grew up in Yerushalayim, Kiryat Sefer, and Bnei Brak. Why did you not find whatever it would have taken to hold on to those neshamos?

“Yes, you consider yourself tzaddikim. You are proud of the fact that you were saved in your teivos. But why do you think I gave you the siyata d’Shmaya to become who you became?”

“In the very description of that covenant in the tochachah, I have stated that ‘all of Israel bears responsibility for one another’s deeds’ (Shevuos 39a).”

Can we honestly say that we did everything?

My rebbi, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, repeated many times the Chazal (Vayikra Rabbah 9:3) about Rabi Yanai, who once met a distinguished-looking person and invited him to eat with him. At the meal, Rabi Yanai tested him in every part of Torah, and found him totally devoid of any Torah knowledge. Rabi Yanai then asked him to lead the bentshing. The guest demurred, obviously unfamiliar with the words.

Rabi Yanai then angrily told him, “Repeat after me: Yanai has fed his bread to a dog.”

The guest grabbed Rabi Yanai and told him, “You have robbed me of my inheritance!”

Rabi Yanai was puzzled. “How so?” he asked.

The guest replied, “I was once passing by a melamed teaching a group of children Torah, and he was saying, ‘Moshe taught us Torah, which is the inheritance of Yaakov’s community.’ He did not say that it was ‘Yanai’s inheritance.’ Rather, he said ‘all of Israel’s inheritance.’ And if you possess it, and are withholding it from me, then you have robbed me.”

It is true that each person has bechirah and will have his own reckoning to face. Other people’s reckoning we leave for them to deal with. But for those who possess Torah, the judgment may be, “If you have it and they don’t, it is you who are withholding it.” It was not given to us alone; it was given to us to share. We are the trustees, charged with the duty of dividing the inheritance appropriately.

Sharing means finding ways to reach those who may even resist the idea. The onus is on us to try to reach them.

This is not only true of those growing up in a secular environment. It is doubly true of the hundreds of Jews who, tragically, have gone “off the derech,” like some of the people who were at the Nova festival on Simchas Torah. The off-the-derech phenomenon has many, many causes: molestation, emotional abuse, family dysfunction, educationally unsuitable institutions, and many more. Our obligation to the next generation is not only to create the next Rav Akiva Eiger, but also to give to each and every child his rightful share in Torah, whether it’s Talmud, Mishnah, Mikra, or derech eretz, so he can dance on Simchas Torah with a fire of joy, holding his share of Torah proudly aloft.

B

ut let’s assume that we have indeed reached out and done everything that we could, but to no avail. Now what?

In Bnei Brak there lives a tzaddik named Rav Z., who works with bochurim who have strayed very far. He wears long levush and is as unassuming as one could imagine. He is the last person we would picture working with those kids. He comes occasionally to the United States to raise money for his one-man operation.

This past Succos, one of “his boys” told him that he intended to go to the Nova festival. Rav Z. tried hard to dissuade him, but the boy wouldn’t hear of it. That evening Rav Z. went to the kever of the Chazon Ish and recited the entire Sefer Tehillim. The next day he spoke to the boy again, but once again to no avail. He went back a second time to the kever and again recited the whole Tehillim. The boy was still adamant.

The boy set off for the festival with friends. On the way, they bought a few bottles of whiskey. They got to their rooms and made a l’chayim. One l’chayim led to another, and soon they were out cold on the floor, so drunk that they never made it to the festival. Indeed, tefillah works if it is said with the intensity and mesirus nefesh of Rav Z.

Have we davened for our children and brethren that Hashem open their hearts? How intense are our tefillos for people crawling through booby-trapped buildings —people whose parents, spouses, and children are sitting on edge, dreading that terrible knock on the door?

B

esides actively davening for our brethren, there is another way to reach out:

“‘You shall love Hashem your G-d,” which means that we should cause Hashem’s name to be beloved through us. This happens when a person learns Mikra and Mishnah, is meshamesh talmidei chachamim, engages in his business honestly, and deals pleasantly with the people around him.

What do people say about him? Fortunate is his father who taught him Torah; fortunate is his rebbi who taught him Torah. Woe to the people who didn’t study Torah. This person who studied Torah, see how pleasant are his ways, see how righteous are his deeds. It is about him that the pasuk says, “And He told me you are My servant Israel, in whom I will be glorified.”

But someone who studies Torah and Mishnah and yet is dishonest in his dealings and does not speak pleasantly with people, what do people say about him? “Woe unto this person who has studied Torah! Woe to his teacher who taught him Torah! For this person who studied Torah, see how destructive are his deeds, and how ugly are his ways. About these people it says, ‘This is Hashem’s nation, yet they had to leave His land!’ ”

(Yuma 86a)

It is quite clear from this Chazal that the most powerful impression we can make on someone is not by teaching, but by interaction. Integrity and pleasantness evoke admiration, even if it is begrudged. Chazal derived this obligation from the same pasuk as the one that obligates us to give up our lives for the love of Hashem!

This means that our obligation to present ourselves with integrity and pleasantness applies regardless of how others interact with us. If a ben Torah is unfailingly honest and true to his word; if he refrains from pushing ahead in the line or snatching a parking spot; if he actively greets people with a smile and pleasantness, do we doubt that more people might be drawn to shemiras Torah u’mitzvos?

And does anyone doubt that the opposite is true? If we are rude and pushy, cutting corners and finding highly doubtful financial heterim, ignoring people around us and being rude, is there any question that we will dissuade people from drawing closer to us?

Navigating appropriate interaction with the world around us is extremely complex. On the one hand, we rightfully need to stay separated and not take part in the general culture. We must teach our children why our identity and our way of life is infinitely superior to those of the secular world. We do not want to mingle in activities that erase these boundaries. We need to teach them that we may have serious fundamental ideological disagreements, even with religious Zionism. We need to stand fast and be resolute about the sacrifices that we cannot and will not make. We will not allow anyone to mold our children. We will not let go of a strong Torah presence in our midst.

But equally important, we need to educate our children that every human being is created b’tzelem Elokim. And most importantly, all our brothers and children who have strayed are just that: our brothers and children. We should be filled with pain and sorrow — the type of pain and sorrow that causes sleepless nights and restless days for the parents of children who have wandered off.

However, in our desire to keep that wall of division as firm as possible, we lose a vital part of our empathy for the rest of our brethren. Why is it that none of the chareidi newspapers can write up detailed accounts of the families of soldiers who have lost their beloved child or father in the war? Not even soldiers whose lives are Torahdig?

Is it not a spiritual loss for our children if they are not taught to sincerely and profoundly empathize? Might not a deep empathy reinforce a sense of responsibility to take their learning more seriously during this difficult period?

In a similar vein: Many in the dati-leumi camp have written sharp critiques about our world. Often, conversations are highly charged. We bristle and shout back. Why is it that we can’t understand their pain? Iyov blasphemed and expressed doubts about hashgachah yet was not held accountable because he was in such pain (Bava Basra 15b). Is it so hard to understand why someone whose husband hasn’t been home in months, or whose 18-year-old son is in the hellhole of Gaza, is crying out in pain? Can we not understand the anguish of those whose loved ones have come back shattered for life, physically and mentally? Is it our duty to yell back, or is it to absorb their pain with compassion and empathy?

T

his brings us to another point about our interaction with the world around us. Recently a newspaper somewhat affiliated with the dati-leumi community published a coarse cartoon derisive of the Olam Hayeshivos. One of the chareidi newspapers published a response that was equally coarse and vulgar, dripping with venom.

Is that our language? After all the time that we’ve purportedly spent learning and developing our character, are we still at the level of, “He started it. I was giving back as good as I got”? These are hallmarks of an unrefined personality. We can choose not to respond, or we can choose to respond in a dignified and thoughtful way. But to become a street fighter?

This is similarly true about the Knesset and politics in general. Politics is all about wheeling and dealing. Both flexibility and inflexibility have their place. But the speeches and public comments are simply for public consumption. They convince no one. Why is it then that we allow ourselves to speak crudely and coarsely, with bluster and arrogance? If chareidi politicians are distinguished by their dress, shouldn’t their speech also set them apart?

“They’ll think that we’re weak if we do that” is a poor excuse. Why does it matter what they think? The strength of our hand depends on the votes we have, and how we play our hand. The cheap exchanges add nothing to it.

What, then, is the proper and productive behavior of our tzibbur when we need to stand strong? We have faced and continue to face many issues on which we cannot compromise, and we must stand firm and resolute. Sometimes an organized protest is the appropriate way to show how deeply we are affected.

Standing firm and not budging are marks of strength. Getting whipped up into a frenzy, fighting and scuffling with police and secular people, yelling “Nazi” and other profanities, and destructive behavior in general are marks of a terribly flawed character. What a chillul Hashem when in our struggles for a Torah way of life we exhibit street behavior! And what a kiddush Hashem it would be if our medium matched our message.

F

inally, we present ourselves as the ones whose Torah is a tremendous zechus for those on the front lines. This is undoubtedly true. But do we live our lives like that? Do we ask ourselves every time we take a break, “Am I endangering someone’s life?”

A few months ago, there was a 20-year-old young man from a Hesder yeshivah named Maoz who fell in battle, Hashem yinkom damo. His uncle, Hagaon Harav Mordechai Linzer, talmid muvhak of Hagaon Harav Asher Arieli shlita, was maspid him.

He said, “When the war started, I thought of the Rashi that says, elef lamateh, elef lamateh — that for each person who went to battle, one person stayed behind to daven. I undertook to be mechazek myself in many different areas for your sake, Maoz, and for the sake of your friends.”

Rav Linzer began sobbing. “I failed you, and I failed every single one of your friends who was killed.” He broke down sobbing uncontrollably. “Maoz, I failed you and I ask for mechilah.”

Are those our feelings?

AS

certain as we are that Mashiach Tzidkeinu is coming, we also know that his coming is accompanied by the most excruciating Yom Hadin. Each person, every community, will undergo its examination.

Hashem will turn to us and ask, “What did you do?” We will meekly mutter something about being in the ohel shel Torah, which is the teivas Noach of our times.

And then Hashem will turn to us most sternly and ask, “Where is everyone else? Where are all those who drowned and were pulled in by the muck?”

We will shrug and say, “What could we do?”

He will thunderously retort, “The voice of your brother’s blood yells out to me! Are you not your brother’s keeper?

“Foolish shepherd, when I miraculously created a teivah in this generation, shouldn’t you have understood that I’m saving you in order to save all the others? Is it only you and your neshamah that are precious to me?

“Did you concern yourself with spreading Torah to each and every community? Did you reach out to those who were purportedly lost?

“Did you find ways to retain those who were falling through the myriad cracks?

“Did your deportment and person create a kiddush Hashem, and draw people to the Torah?

“Minimally, did you at least daven for all those lost and estranged neshamos?”

If we must face these questions without adequate answers, woe unto us on the day of rebuke, when Hashem will judge each and every one of us for who he is!

May we look beyond our teivah to the beautiful yet corrupted world around us and do all we can to bring our fellow Jews on board.

May we not be ashamed on that day.

מָה הֵשִׁיב הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךָ הוּא לְנֹחַ כְּשֶׁיָּצָּא מִן הַתֵּיבָה וְרָאָה אֶתּ הָעוֹלָם חָרֵב והִתְּחִיל לִבְכּוֹתּ לְפָּנָיו וְאָמַר רִבּוֹנוֹ שֶׁל עוֹלָם נִקְרֵאתָּ רַחוּם הָיָה לְךָ לְרַחֵם עַל בְּרִיוֹתֶּךָ וְכוּ’. הֶשִׁיבוֹ הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךָ הוּא וְאָמַר. רַעֲיאָ שָׁטְיָיא, הַשְׁתָּא אֲמַרְתָּ דָּא, לָמָה לֹא אֲמַרְתָּ בְּשַׁעְתָּא דְאֲמָרִיתּ לָךָ, כִּי אוֹתְּךָ רָאִיתִּי צַּדִּיק לְפָּנַי וְגוֹ’. וְאַחַר כָּךָ, הִנְנִי מֵבִיא אֶתּ הַמַּבּוּל מַיִם. וְאַחַר כָּךָ, עשה לְךָ תֵּיבַתּ עֲצֵּי גוֹפֶּר. כָּל הַאי אִתְּעֲכָּבִיתּ ואֲמָרִיתּ לָךָ בְּגִין דְּתַּבְעֵי רַחֲמִין עַל עַלְמָא. וּמִכְּדֵין שְׁמָעְתָּא דְתִּשְׁתְּזִיב בְּתֵּיבוּתָּא לָא עָאל בְּלִבָּךָ לְמִבְעֵי רַחֲמִין על יִשׁוּבָא דְעַלְמָא ועֲבָדְתּ תֵּיבוּתָּא וְאִשְׁתְּזִיבַתּ וּכְעַן דְּאִתְּאֲבִיד עַלְמָא פַּתָּחְתּ פּוּמָךָ לְמַלְּלָא קֳדָמָי בַּעְיָין וְתַּחֲנוּנִים. כֵּיוָן דְחָזָא נֹחַ כָּךָ, אַקְרִיב קָרֵבָּנִין ועֲלָוָון דִּכְתִּיב (בראשית ח’) וַיִּקַּח מִכָּל הַבְּהֵמָה הַטְהוֹרָה וּמִכָּל הַעוֹף הַטָהוֹר וְגוֹ’

Zohar 1, 67b

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1033)

Oops! We could not locate your form.