The Power of This Day

| September 29, 2024A fresh transport, just in from Antwerp, had arranged the unthinkable: A Rosh Hashanah service behind one of the barracks

Unesaneh tokef kedushas hayom — Let us relate the power of holiness on this day.

Yom Hadin in Auschwitz: The cantor raised his voice on the altar of Hashem’s Will.

Ki hu nora v’ayom — For it is awesome and frightening.

The stench of ascending neshamos permeated the field and lifted the haunting tune to the heavens as huddled prisoners surrendered their torn hearts to the One Above.

A fresh transport, just in from Antwerp, had arranged the unthinkable: A Rosh Hashanah service behind one of the barracks.

It’s a death sentence. Suicide. We don’t do this here, was the initial reaction of the seasoned inmates, but one by one, their broken souls yearned to join.

Teenager Henry Berger stood at the edge of the group of newcomers, trembling with the knowledge that a person could be shot for a far lesser offense. But he was mesmerized, the melody a balm for his aching soul.

“Abie,” he told his son, my husband, decades later, “I can still hear the chazzan’s beautiful high tenor, even as I speak to you now.”

A Nazi patrolling the hill above spotted the motley minyan and came barreling down.

“Achtung!” he bellowed, and aiming his rifle at the shaking Jews.

Mi yichyeh u’mi yamus — Who will live and who will die.

The cantor’s singsong pleaded to his Master. He bowed in humility, oblivious to the raging angel of death — and the Nazi froze, transfixed by the scene. His mouth gaped in awe.

Mi yishafel u’mi yarum — Who will be degraded and who will be exalted.

The cantor’s voice rose to a crescendo and then crashed, spent.

The guard regained his senses. He lowered his rifle.

“Get out of here,” he barked. “And don’t ever think of doing this again.”

He turned and marched away, back through the fires of hell, and young Henry dashed back into the barracks, heart beating furiously, the Rosh Hashanah miracle seared into his devastated psyche.

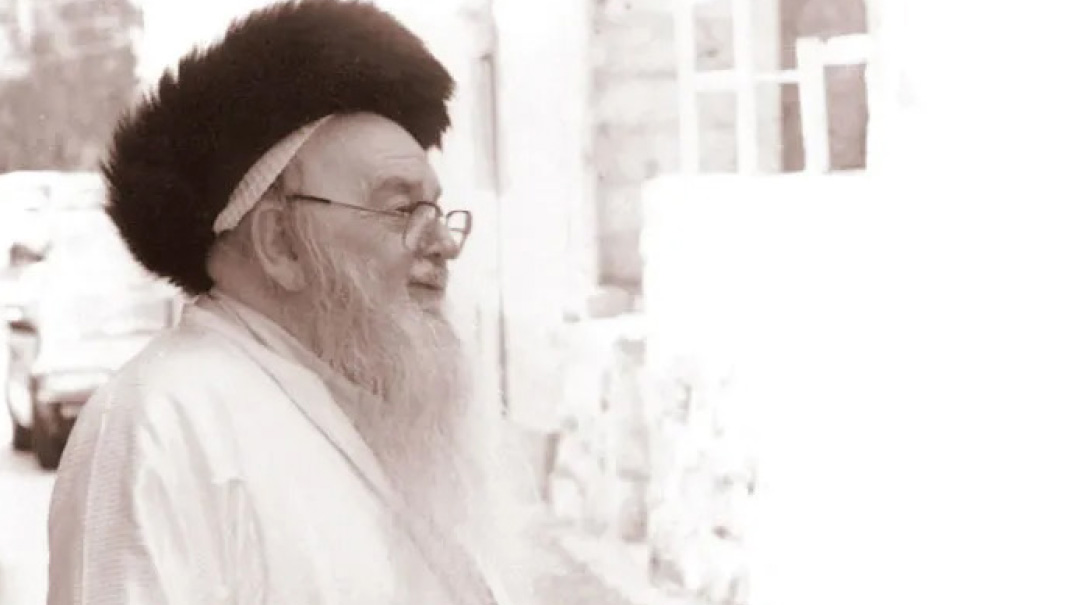

Binyomin Tzvi HaKohein Berger, my father-in-law, was born in 1926 to a simple, G-d-fearing family in Leipzig, Germany. As he approached his bar mitzvah, the noose tightened around the neck of German Jewry, and he and his parents and sister fled for France. They found sanctuary on a farm for over a year, but the Vichy regime, collaborating with the Nazis, clawed out hidden Jews and threw them onto trains bound for Auschwitz.

Yisgadal v’yiskadash. With the gesture of an index finger, Henry’s mother Tzera Baila and little sister Sluva, may Hashem avenge their blood, were ordered to the gas chambers.

Shemei Rabba. His father Avraham, may Hashem avenge his blood, struggled valiantly for over a year until he, too, succumbed.

Young Henry, alone in this world, defied the odds for nearly four harrowing years.

An interviewer for Steven Spielberg’s archives would later ask him, “Tell me, what was Auschwitz like?”

My father-in-law looked straight at the camera with a sparkle in his eye and chuckled. “Well, it wasn’t the Hilton.”

He kept most of his miraculous stories of survival to himself, but a few slipped through. Once he recalled the time he contracted typhus in the camp. They dragged him to the makeshift hospital, where rows of helpless Jews lay in agony on the floor. The Nazis walked into the ward and began shooting, one by one. He was in a feverish haze as they approached.

“This one is already almost in the next world, why waste a bullet?” he heard one say. They moved on.

Fast-forward through five successful decades in America and zoom in: a fiercely loyal husband and proud, devoted father of five children, grandfather of numerous grandchildren, a retired furrier who spent part of the year in Miami, looking forward to his third Daf Yomi siyum.

He was biking, as he often did, and then — Boom! A crash, his body broken.

U’teshuvah, u’tefillah, u’tzedakah. For more than a half a year my father-in-law flitted between life and death. He was a veritable shofar, echoing his mesirus nefesh for Rosh Hashanah davening in the camps, his weeping arousing people from their slumber, the catalyst for an outpouring of merits on his behalf. He loved Yom Tov, and one of his last mitzvos was shaking the lulav while strapped in his wheelchair, his breathing belabored as he recited the brachah.

V’samachta b’chagecha. Several hours after Hoshana Rabbah ended, once we had already begun Yom Tov, my father-in-law’s mighty spirit left his broken body. It soared to the heavens to dance with the letters of the sefer Torah, his neshamah entwined eternally with Simchas Torah.

Can anyone really fathom the kedushas hayom?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1031)

Oops! We could not locate your form.