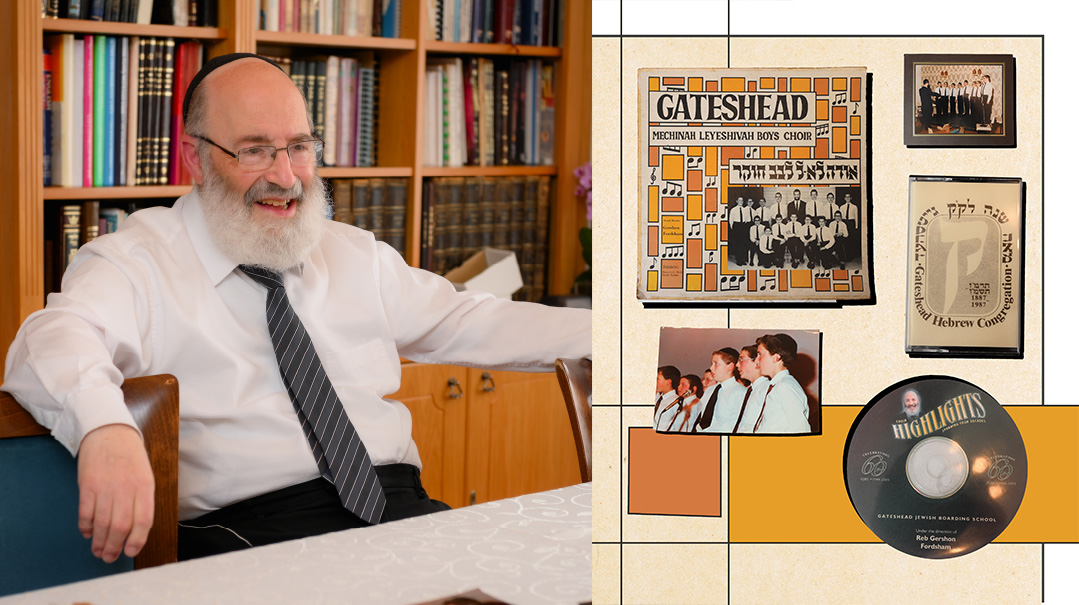

Still Singing His Song

| September 29, 2024Reb Gershon Fordsham's nusach, replicated throughout decades and continents, is still dependably the same

Photos: Ruskin Photography

From the time Rabbi Gershon Fordsham was a child in the Adath Yisroel shul choir in the 1950s, he was laying the foundations of his future as a renowned Yamim Noraim baal tefillah. But not only. Along the way, he directed one of the first choirs of the golden Pirchei era, even putting out a record in 1968. While a lot has changed since then, Reb Gershon’s nusach, replicated throughout decades and continents, is still dependably the same

The annual spectacle of British synagogue pomp on Simchas Torah night was the high point of the year at the Adath Yisroel shul (the Adass) in 1950s Stamford Hill, London. Crowned by a top hat, flanked by the shul’s committee and honorary officers, the chassan Bereishis made his entrance from a side room just before the start of Maariv. As the procession made its way across, all eyes would turn to watch the choir boys, who stood at attention on the bimah, awaiting their cue. With a swish of his hand, conductor Moshe Grunfeld had them belting out a festive “Ma Tovu” that kicked off the Simchas Torah celebrations, accompanying the “celebrity for a day” as he made his way in majestic parade through the brightly lit sanctuary to his seat.

For many of those boys, the shul choir was the sum total of their musical career. But for one enthusiastic recruit, the group’s Shabbos and Yom Tov performances were the inspiration for what would become a life-long calling at the amud and the microphone.

For young Gershon Fordsham, the Adass’s decorum and the chazzan’s emphasis on a carefully crafted nusach hatefillah were elements that formed the solid foundations of his future as a renowned Yamim Noraim baal tefillah — first at the Gateshead Jewish Boarding School and then at Gateshead Yeshiva. Along the way, he also launched a career as venerated director of the Gateshead Jewish Boarding School choir, producing acclaimed albums and appearing at countless performances spanning decades.

The grandeur of Simchas Torah in one corner of London created a Gateshead legend of chinuch, nusach and neginah whose influence has spread worldwide. Rabbi Gershon Fordsham’s engaging nusach is so acclaimed that it has been copied by probably hundreds of baalei tefillah in shuls as far away as Eretz Yisrael, South Africa, and Australia. And it’s not because his davening is peppered with dramatic Rosenblatts and sophisticated Kwartins; on the contrary, its appeal lies in its warmth, masterful simplicity, and sheer predictability.

“The first time I heard him, it occurred to me once davening had ended that I had been totally engaged in the machzor throughout Mussaf of Rosh Hashanah, following every word inside with interest,” says Reb Chaim Boruch Katz, himself a twenty-year veteran of the amud and a son-in-law of Rabbi Fordsham. “Normally, people can find themselves flipping pages, waiting around for a highlight here or a shtickel there, but with Reb Gershon, the secret is that you’re engaged throughout.”

But as any Gateshead Jewish Boarding School grad will tell you, for Reb Gershon, it’s not just about the high profile Yamim Noraim tefillos, it’s about every weekday davening. Any freshly minted bar mitzvah boy wanting to lead a weekday Minchah was tested in advance by Rabbi Fordsham to ensure he was prepared to lead the tzibbur in the proper way.

“In Adass, the davening was a davening. Already as young children, we learned the meaning of decorum, the right approach to tefillah, and how tefillah should look,” says Rabbi Fordsham.

After decades at the amud of Europe’s most prestigious yeshivah, those lessons have spread far and wide.

Oops! We could not locate your form.