The Myth of the Misplaced Name

| September 24, 2024Few threads are as colorful as the story of immigrants’ names being changed at Ellis Island

Title: The Myth of the Misplaced Name

Location: Ellis Island

Time: 1945

Moses Schmelowitz made a small fortune on the black market during World War II. The first thing he did was to change his name to E. Lincoln Saunders. After that, he and his wife decided to move from Williamsburg to Central Park South.

To celebrate this happy occasion, they arranged for a party in their apartment on a Saturday night, to which they invited their old cronies and friends. At the last moment, Mo decided to invite his widowed mother, who lived in Williamsburg.

The happy occasion arrived. Champagne was flowing and an orchestra was regaling the guests. The clock struck eight, then nine, and his mother was not there. His mother did not have a phone, so he called her neighbor. She informed him that his mother had left some two hours ago.

By ten o’clock, Mo called the police. After all, he was still a son. At eleven o’clock, he called the FBI. He had spent a fortune on the party, and now the whole evening was ruined for him.

At 3 a.m., when he was seeing his last guests out, he noticed that in the lobby in front of the fireplace, a little old lady was huddled in a chair, asleep. He recognized his mother.

He ran over to her and shouted, “Mama, Mama! Thank G-d you’re all right. Where were you?”

She opened her eyes and slowly said to him, “I’ll tell you the truth, son, I didn’t remember your name.”

—Rabbi Isaac Trainin

IN the rich tapestry of American Jewish history, few threads are as colorful as the story of immigrants’ names being changed at Ellis Island. It’s a tale passed down through generations, often with humor and pathos — the bewildered immigrant facing an impatient or ignorant official who, with a pen stroke, transformed Cohen to Kane or Goldstein to Stone.

But what if this cherished anecdote, repeated in countless biographies and shared on many a first date, is more myth than history? Recent scholarship strongly suggests that this might indeed be the case, prompting us to reexamine not just this particular story, but the larger narrative of the American Jewish immigrant experience.

For decades, American Jews have shared stories of how their ancestors’ names were changed upon arrival at Ellis Island. These accounts often paint a picture of harried immigration officials, language barriers, and the transformation of distinctly Jewish names into more “American” versions. However, historical records tell a different story.

Immigration procedures at Ellis Island were quite rigorous and systematic. Names of arriving immigrants were taken from ship manifests, which were prepared at the ports of departure. These manifests were based on passports and other official documents. Ellis Island officials were not tasked with recording names but with checking immigrants’ papers against these pre-existing lists. Shipping companies screened passengers in advance to ensure they met US entry requirements, as they were liable for costs if passengers were denied entry and deported.

Moreover, Ellis Island employed a cadre of interpreters fluent in dozens of languages, including Yiddish. Aid organizations like HIAS provided additional assistance in the form of lawyers (Yiddish-speaking, of course!) to those who had issues with immigration officials. The idea that Jewish immigrants couldn’t communicate their names effectively doesn’t align with the historical reality of the immigration process.

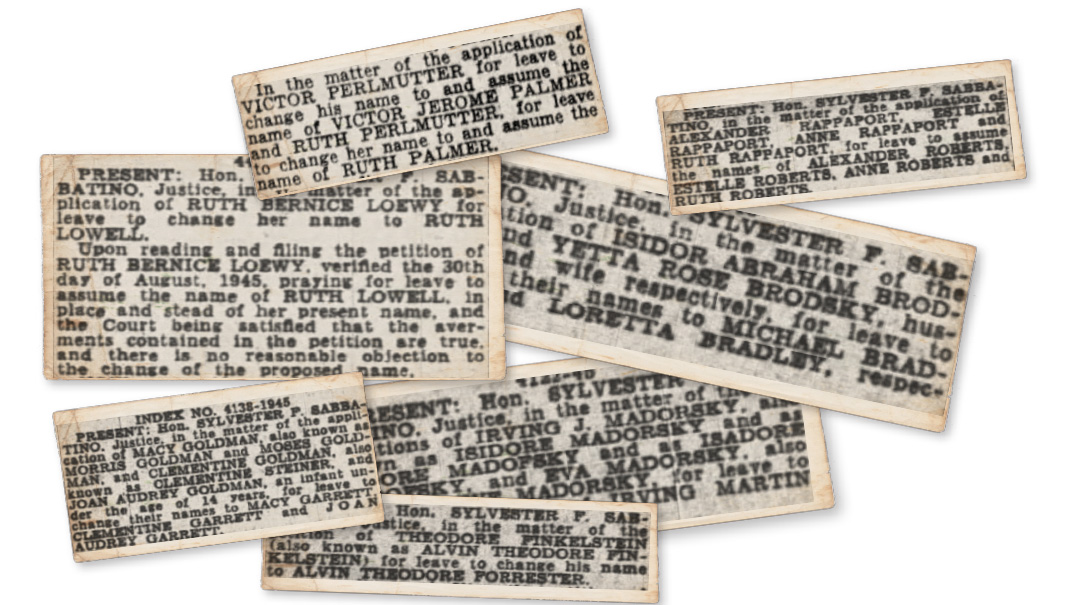

So if names weren’t changed at Ellis Island, how did so many Jewish immigrants end up with Americanized names? The answer suggests a process that was far more gradual than that in the Ellis Island myth. The Jewish immigrants changed their own names, and generally did so legally after settling in America. Court records from the early 20th century reveal thousands of petitions filed by Jewish immigrants seeking to alter their names. These readily available documents provide a window into the reasons behind most of these name changes.

Petitioners often cited practical concerns: names that were difficult for Americans to pronounce or spell, or Eastern-European-sounding names that were perceived as obstacles to employment or social climbing. Some explicitly mentioned that their names sounded “un-American” or were an “economic handicap.” However, reading between the lines of these petitions, one senses a deeper, often unspoken motivation: the desire to assimilate into American society and escape the specter of anti-Semitism.

Early 20th century American society was marked by significant anti-Semitism — although it was a decidedly different type of anti-Semitism from what Jews had faced back in Russia. Jews in the US faced discrimination in employment, education, and social settings. Changing one’s name was often seen as a necessary step toward acceptance and success in the new world. In most cases, the name change did not accomplish much, though it did open doors for the next generation — albeit at a heavy cost to the Jewish nation.

Perhaps Lincoln Rutherford Harrison, the son of the former Moshe Hasenfeld, was able to gain acceptance to Harvard or a local country club, not just because he had a gentile-sounding name, but because he had acclimated and completely assimilated into his new surroundings. Sadly, the cost of this transformation was not just the one-dollar clerk fee, but more often than not, the permanent loss of his or her connection to the Jewish nation.

Before Ellis

Ellis Island, which opened in 1892, was established as a centralized immigration processing station to manage the growing immigrant influx into the United States. Prior to its opening, immigrants were processed at various ports, with Castle Garden in Manhattan serving as the primary entry point for many. The system was decentralized, inefficient, and often chaotic, leading to overcrowding and inadequate medical and legal checks. As the number of arrivals surged, particularly from Southern and Eastern Europe, the federal government saw a need for a more organized and regulated process, ensuring better medical examinations, legal checks, and record-keeping, which Ellis Island provided in a single location.

A Chassidic Conundrum

Of course, no mention of Ellis Island would be complete without the inclusion of this classic tale, which illustrates the confusion created by chassidic marriage patterns:

At Ellis Island, a Rebbe and Rebbetzin from the illustrious House of Chernobyl stood before an immigration officer.

“Name?”

“Twersky.”

He glanced at the Rebbetzin. “Your name?”

“Twersky.”

“Maiden name?”

“Twersky.”

The officer, now irritated, turned to the Rebbe. “Your mother’s maiden name?”

“Twersky.”

He repeated, slowly, “Your mother’s maiden name?”

“Twersky.”

Frustrated, the officer yelled, “And your grandfather’s mother’s maiden name?”

In unison, “Twersky.”

Flustered, the officer called his supervisor, muttering, “This rabbi doesn’t understand English.”

The Rebbe smiled. “No, sir. Your immigration officer doesn’t understand Twersky.”

Thank you to Chaya Sarah Herman and (name your favorite) Twersky for their assistance with this article. A Rosenberg by Any Other Name: A History of Jewish Name Changing in America by Kirsten Fermaglich is an excellent source for more information on this topic.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1030)

Oops! We could not locate your form.