The Last Leader

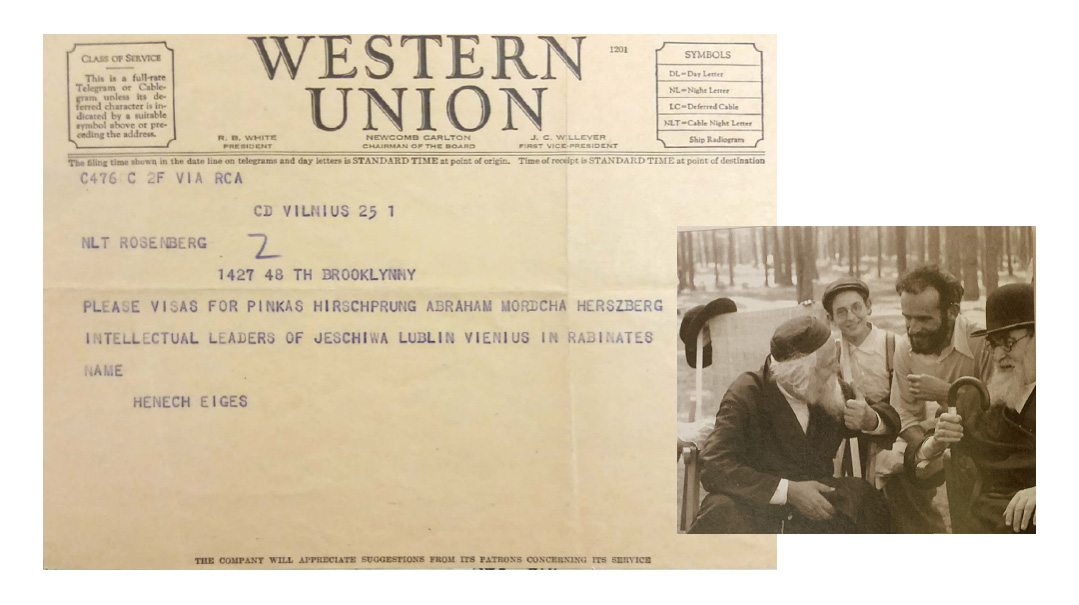

| September 17, 2024Rav Chanoch Henoch Eiges, immortalized as the Marcheshes

Title: The Last Leader

Location: Vilna

Document: Telegram

Time: 1940

While Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski led Vilna’s beis din and the prewar Torah world, another luminary served quietly beside him for over 40 years: Rav Chanoch Henoch Eiges, immortalized as the Marcheshes after his renowned sefer.

Despite his unassuming nature, Rav Eiges was a giant in his own right. He served as a dayan until his tragic martyrdom during the Holocaust. Though he often served in Rav Chaim Ozer’s shadow, the Marcheshes’s scholarship and halachic brilliance continue to illuminate the Torah world to this day.

Rav Chanoch Henoch was born in the Lithuanian city of Raseiniai around 1864. His father, Rav Simcha Reuven Edelman, was a businessman who was a great Torah scholar and a renowned writer. (He reverted to the original family name, Edelman, while the rest of the family had adopted the name Eiges from his grandmother’s side. It’s possible Rav Simcha Reuven changed back to the original surname to avoid the czarist draft.) Young Chanoch Henoch received Torah instruction from the local rav, the Torah giant Rav Alexander Moshe Lapidos. Rav Chanoch Henoch later studied in Volozhin, following short stints in several other yeshivos around Lithuania.

In 1898, he married Hinda, a granddaughter of Rav Shmuel Lubtzer (Zivertansky), a famous dayan on the Vilna beis din. In 1898, Rav Eiges was appointed to the prestigious position on the beis din to succeed his wife’s grandfather, and he’d maintain that position for the next 43 years until he was murdered in the Holocaust.

To a large extent, his career was defined by his long association with the Vilna beis din, and specifically his close collaboration with Rav Chaim Ozer on myriad issues. The two signed together on tens of proclamations, collections, and public pronouncements over the decades. Rav Chaim Ozer’s famous “kibbutz,” which was sort of an informal yeshivah for exceptional youth in Vilna, was actually run jointly with Rav Chanoch Henoch Eiges, the latter delivering regular shiurim to its members and granting rabbinical ordination to young rabbinical candidates.

The Marcheshes was also Rav Chaim Ozer’s partner in establishing the Knesses Yisrael political organization. The czarist government ultimately didn’t permit it to launch, but the effort foreshadowed future initiatives in the Orthodox political realm.

In 1910 Rav Chaim Ozer and Rav Chanoch Henoch were elected as Vilna’s representatives to the famous St. Petersburg rabbinical conference in 1910. At the conference, the Marcheshes sat on a committee on reforming the kehillah infrastructure in the Pale of Settlement. In this age of rapid secularization, Rav Itzele Ponevezher proposed that the right to be elected to public office within the kehillah be limited to those who attend shul, thereby keeping communal leadership in the hands of the Orthodox.

The Haynt newspaper provided day-to-day coverage of the St. Petersburg rabbinical conference, and they reported the Marcheshes’s reaction to Rav Itzele Ponevezher’s proposal.

The Vilna representative Rav Chanoch Henoch Eiges concurred with this view, and cited a pasuk in support: Som tasim alecha melech mikerev achecha, a leadership position in the Jewish community must be held only by someone who adheres to Jewish tradition. The inference was that the Orthodox didn’t consider secular Jews to be truly within the community. The few solitary words uttered by the quiet, unassuming and wise Rav Henoch caused a great turmoil in the room. This had not been his intention, and he seemingly didn’t realize the ramifications of his statement. The secular members of the committee loudly protested this assertion.… The misunderstanding was cleared up by the rabbi of Minsk, Rav Eliezer Rabinowitz.

The Marcheshes had a noteworthy affiliation with the religious Zionist Mizrachi party. Like many Lithuanian rabbis of his era, Rav Chanoch Henoch had a strong affinity for the early Chibas Zion movement and later the Zionist movement. Following the 1917 Balfour Declaration, he formally joined the Mizrachi and served as one of its public rabbinical leaders. Over the ensuing years, he attended Mizrachi conferences in Vilna and Warsaw. At the 1923 conference, he was elected to the presidium, and at the 1927 conference, he was elected its national chairman.

In 1929, he publicly broke ranks with Mizrachi over its support for the candidacy of Rav Yitzchak Rubinstein as chief rabbi of Vilna, which the Marcheshes and many others felt was a public affront to Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski. Though he no longer served in any official capacity in Mizrachi after this incident, he still encouraged emigration to Eretz Yisrael.

During this entire time, he sat side-by-side on the Vilna beis din with his dear, lifelong friend Rav Chaim Ozer, the latter serving as the one of the primary rabbinical leaders of the rival Agudas Yisrael party, which opposed Mizrachi and Zionism altogether. This political and ideological divide didn’t seem to affect their relationship in the slightest, and they continued serving Klal Yisrael together until the end of their lives.

With Rav Chaim Ozer’s passing in August 1940, the Marcheshes was recognized as the elder rabbi of the Vilna beis din, and hence the leader of Vilna’s Jewish community at a most trying time in its storied history. He would be the last such leader of “the Jerusalem of Lithuania,” as the Vilna community was massacred less than a year later.

In the last months prior to the Nazi invasion, the Marcheshes served as leader of the refugee yeshivah community that had sought refuge in Vilna and its environs in the early weeks of the war. The Joint supported these refugees, and much of the funding went through the Marcheshes. Shortly following the Nazi invasion in June 1941, the Marcheshes was brutally murdered. The date of his yahrtzeit is said to be the 15th of Elul, though some have argued that he was killed during the month of Av.

A Tale of Two Shidduchim

In 1909, when Rav Yechezkel Abramsky moved from Telz to Vilna’s Ramailes Yeshivah, he impressed the Marcheshes, who recommended him to his cousin (the Ridbaz’s son-in-law) Rav Yisrael Yonasan Yerushalemsky for his daughter Hendl Reizel. They married that year in her hometown of Chervyen.

Years earlier, the Marcheshes himself benefited from a similar shidduch. Studying in Kovno’s Nevyozer Kloiz, he caught Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor’s attention. When Rav Shmuel Lubtzer sought a match for his granddaughter Hinda, Rav Yitzchok Elchanan strongly recommended the young Marcheshes. These interconnected stories highlight how gedolei Yisrael often played crucial roles as matchmakers, shaping future generations of Torah leadership.

Torah Legacy

As a young man, he penned Minchas Chanoch, a sefer delving into Kodshim-related topics. However, it was his magnum opus, the two-volume Marcheshes, that solidified his reputation as one of the preeminent Torah thinkers of his generation. Marcheshes was published in two parts. The first volume, published in 1931, focused on topics in Orach Chayim and Yoreh Dei'ah, while the second volume, released in 1935, covered Even Ha'Ezer and Choshen Mishpat. These works showcased his unique blend of razor-sharp analysis and classical Lithuanian lomdus. His writings offered profound insights into complex Talmudic sugyos and intricate halachic discussions. While the Marcheshes engaged in contemporary approaches to learning, his work remained firmly rooted in the mesorah of his Vilna forebears.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1029)

Oops! We could not locate your form.