Mussolini’s Mediterranean Menace

| September 3, 2024A two-year campaign by the Axis powers to bring the war directly to Mandatory Palestine

Title: Mussolini’s Mediterranean Menace

Location: Mandatory Palestine

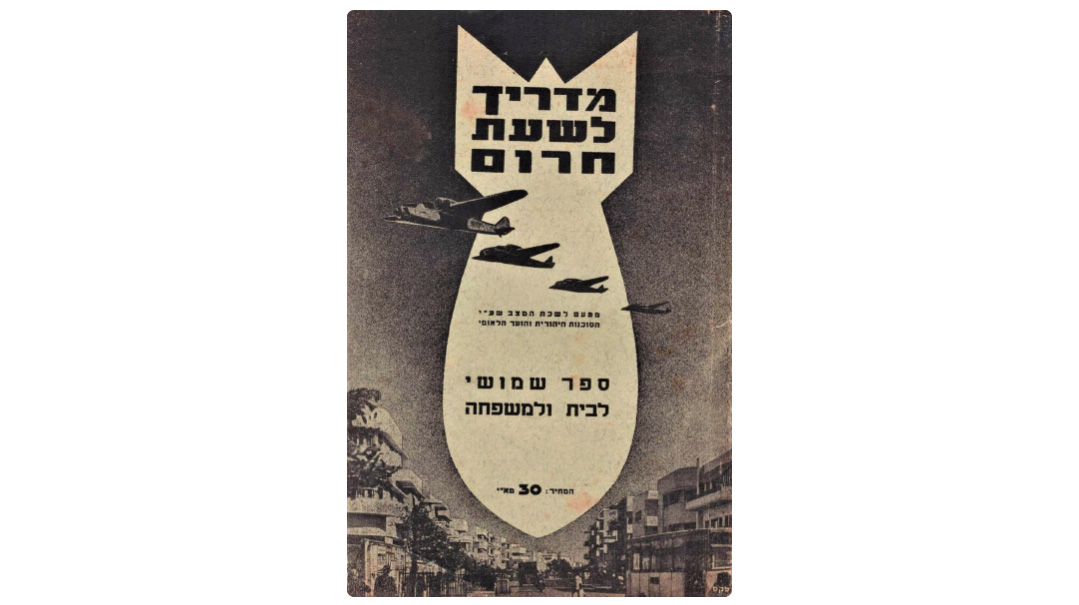

Document: Emergency Air Raid Guide

Time: Summer 1940

ON a warm July evening in 1940, the skies over Haifa erupted with the unfamiliar blare of air raid sirens. As people rushed to shelters, the drone of aircraft engines filled the air. This raid, carried out by a group of five Italian bombers commanded by Major Ettore Muti, marked the start of a two-year campaign by the Axis powers to bring the war directly to Mandatory Palestine.

This assault was rooted in a change in military strategy in the mid-1930s when Italy, under Benito Mussolini’s rule, began viewing Britain as a potential foe. The Italian military had been eyeing targets in the eastern Mediterranean, including Palestine, since the Ethiopian War of 1935–36. Haifa, with its oil refineries and British naval base, was of particular interest to Italian strategists.

When Italy entered World War II on June 10, 1940, the stage was set for conflict in the region. The first raid on Haifa took place on July 15, 1940. Taking off from the Greek Dodecanese Islands (among them Rhodes), Italian bombers struck the Iraq Petroleum Company installation, setting three oil tanks ablaze and temporarily cutting the city’s power supply. Two Arab civilians were severely injured, one of whom later died. Anti-aircraft guns positioned on Mount Carmel did little to slow the raids.

The deadliest attack came on September 9, 1940, when Italian bombers struck Tel Aviv. Unlike Haifa, Tel Aviv was an open city without military targets and lacked early warning stations or anti-aircraft guns. The raid killed 137 people, including 117 Jews, seven Arabs, and an Australian soldier. Even as London was being targeted mercilessly by the German Luftwaffe, Winston Churchill sent a message of condolence to Tel Aviv mayor Israel Rokach following this devastating attack.

The civilian victims of the Tel Aviv bombing would lead to historical controversy. Italian historian Alberto Rosselli offered the questionable explanation that Italian bombers were initially en route to attack Haifa’s strategic port and refineries but were intercepted by British aircraft. Forced to change course, they allegedly received orders to target Tel Aviv’s port instead. In their attempt to evade British pursuit, the Italian bombers mistakenly dropped their payloads on a civilian area near the port.

The Italian air campaign intensified in September 1940, coinciding with Mussolini’s offensive against Egypt launched from Libya. On September 21, a raid on Haifa killed 40 Arab civilians and damaged the oil refineries, a mosque, and a Muslim cemetery. Ironically, this attack undermined Italian propaganda efforts aimed at courting Arab support against the British.

The German Luftwaffe joined the assault in 1941, bringing more advanced tactics and larger bomber formations. Their first major raid on Palestine occurred on the night of June 9–10, 1941, when about 20 German aircraft bombed Haifa. Local Jewish recruits, who had recently joined the Palestine Light A A Battery, fired their Breda guns at the enemy for the first time.

Even Vichy France briefly entered the fray. On June 11, 1941, a single French Glenn Martin 167F attempted to bomb Haifa but was shot down near Tiberias. A few weeks later, on July 2, French aircraft bombed a prisoner of war camp, killing two inmates and injuring 35.

The raids had significant impacts beyond the immediate destruction. They galvanized the Yishuv’s war effort, with thousands of Jews volunteering for British forces. The military experience that Jews of the Yishuv gained in civil defense would later prove crucial in the 1948 War of Independence.

Ultimately, the Axis bombing campaign failed to achieve substantial military or political objectives. It did not force the British to divert significant air force assets from Egypt to Palestine. Instead, it led to increased recruitment of Palestinian Jews into artillery and anti-aircraft units. The attacks also failed to reignite anti-British sentiment among Palestinian Arabs as the Axis powers had hoped.

By late 1941, the threat of air raids on Palestine began to diminish as the Luftwaffe focused on the Eastern Front. Sporadic attacks continued into 1942, but they were largely ineffective. The last recorded raid took place on September 3, 1942, targeting Haifa once again.

Pipeline to Progress

The Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) refinery in Haifa was a crucial piece of British strategic infrastructure in the Middle East. In the 1930s, the British-controlled IPC constructed a 942-kilometer pipeline from the oil fields of Kirkuk in northern Iraq to Haifa. This engineering marvel, completed in 1934, allowed Iraqi oil to be efficiently transported to the Mediterranean coast, where it could be refined and shipped to European markets.

The Haifa refinery began operations in 1939, and complemented earlier plans for a railway connecting Haifa (and thus the Mediterranean) with Baghdad, intended to secure British imperial interests. The refinery provided a reliable fuel supply for Britain’s Mediterranean fleet and forces in Egypt, and offered an alternative to the vulnerable Suez Canal route. The repeated bombing raids on Haifa throughout 1940–42 were calculated attempts to sever a vital artery of the British war machine in the Middle East.

Yerushalmi Victim

The majority of the Jewish victims of the Italian bombing of Tel Aviv were buried in a mass grave in the Nachalat Yitzchak cemetery in Givatayim. Some were taken by family members and buried in private graves in various cemeteries around the country.

One such burial on Har Hazeisim was for Rav Chaim Talaisnik (Rosenman-Cooperschmidt), a prominent Karlin chassid from Jerusalem. Born in 1853 in Russia, he walked on foot to Eretz Yisrael in 1880. Remaining devoted to the rebbes of Karlin throughout his long life, he returned there at least twice, and was instrumental in building the Karlin community in Jerusalem. He established the Karlin shtibel in the Beis Yisrael neighborhood, donated much of the funding for its building and upkeep, and served as its gabbai for decades.

He earned the sobriquet Talaisnik by opening the first tallis factory in Jerusalem. He later opened a matzah bakery in the Beis Yisrael neighborhood, where most of the great tzaddikim of Jerusalem would bake their matzos. His son Leibush continued the bakery, still known today as Leibeleh’s and operating in its original Beis Yisrael location. Rav Chaim Talaisnik was living in an old age home in Tel Aviv when he was tragically killed during the Italian bombing at age 88.

Special thanks to Hollywood-based genealogist and producer Zvi Rosenman, scion of a prominent Yerushalmi family and proud of his Karlin chassidic heritage, whose research was utilized in the preparation of this column, and who is an inspiration and influence on his entire family.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1027)

Oops! We could not locate your form.