The Art of the Contract

| August 20, 2024Magnificent illuminated kesubos came into their own over the last 500 years

Photos: Ardon Bar-Hama; The National Library of Israel

From Morocco to Spain to Italy to India and beyond, magnificent illuminated kesubos came into their own over the last 500 years, bequeathing to our generation both classic works of art and an important historical record. What family secrets lie hidden within the ancient words surrounded by Renaissance art, and what stories do they tell? Perhaps you might discover your own ancestors along the way

It’s a binding agreement, setting out responsibilities and obligations of a new partnership. It’s a document protecting the monetary rights of women.

And it can also be a work of art, displayed on a couple’s living room wall or hanging in an art gallery or museum.

It’s a kesubah, the marriage contract first discussed two thousand years ago in the Talmud, and while it’s actually a technical document and not, as some assume, a promise of ardent dedication and commitment, it is until today the foundation of every Jewish home.

The National Library of Israel (NLI) owns or has online access to some 7,000 kesubos. The oldest kesubah in the collection, from Tyre, Lebanon, is dated 1023, just over 1,000 years ago. But kesubos go back much further. The Talmud in Shabbos 14b credits Shimon ben Shetach as the codifier of the kesubah, the marriage contract that sets out marital and financial responsibilities of the husband toward his wife.

The earliest written kesubah known is dated almost 2,000 years ago, before the Bar Kochba rebellion in 132 CE. In a cache of documents found in a cave near Ein Gedi, archaeologists found a kesubah belonging to a woman named Babatha, given to her by her second husband, Yehuda. The wording of the kesubah, written in Aramaic as kesubos still are today, would be familiar to us, but there was one major difference between then and now: In those days, men could have more than one wife, and Yehuda already had another wife, Miriam. From other documents we discover that Babatha went to court after Yehuda’s death to fight that other wife and her family to retain possession of four date orchards she was entitled to as part of her kesubah.

Historians revel in analysing kesubos, for one practical reason at least: every kesubah opens with the date and place of the marriage and the names of the bride and groom and their fathers, which is a great start for historical or genealogical research. But kesubos don’t just give historians insight into families; although the structure and text of kesubos through thousands of years has remained remarkably consistent, a close look at each one can reveal differences in the culture of Jewish communities all over the world.

Decorative kesubos became popular in 17th and 18th-century Italy. They retained the traditional structure and text, though some included a listing of tena’im, contractual conditions, including the delineation of who will pay for what. Hand-painted on large parchments, they included Biblical scenes connected with marriage, pesukim, flowers, birds, and geometric designs — works of art on public display at the weddings. They often included architectural motifs such as columns and pillars (appropriate for a document that is the foundation of a Jewish home).

Historians suggest possible reasons for the development of the kesubah into an art genre. Perhaps it had to do with the influence of the Renaissance, with its focus on beautiful painting and sculpture. But there is a more practical reason as well: Kesubos are read and seen at weddings, and rich individuals could flaunt their wealth by commissioning expensive, magnificent, hand-illustrated kesubos.

The NLI recently made its own “shidduch” with Swiss private Judaica collector René Braginsky to create a dazzling exhibit of kesubos from the last 500 years. The “Encounters of Beauty” exhibit, open until the middle of September, is an invitation for the public to the “wedding” of two major collections of kesubos, to examine the intricate beauty of these marriage agreements and to wonder at the stories they tell. Look at them closely and you might even feel like a guest at weddings of Jews from different times and places (and you don’t even have to bring a gift).

Wife Number Two

Morocco, 1784. The marriage of Yosef ben Yehoshua to Gracia bas Shlomo. Many kesubos included standard conditions, including forbidding taking a second wife. The kesubah states that this condition doesn’t apply here — Gracia was already wife number two.

To Uphold Your Brother

Moshe ben Yisrael Pesach married Speranza bas Yehudah Oscoli in Italy on Tu B’Av, 1779. Happy anniversary, 245 years ago this week! This unusual marriage was one of yibum, a levirate marriage: Speranza had been married to the chassan’s brother, Efraim Pesach, who had died without children. The kesubah is less decorative than others from that era, understandable under the circumstances. Appropriately, the border quotes pesukim from Megillas Rus, in which the concept of yibum is central, including the brachah for Rus to become a Mother in Israel like Rachel and Leah, and the mention of the other famous case of yibum in the Torah, that of Yehudah and Tamar.

Was this couple blessed with a son to bear the dead brother’s name? We don’t know. But the kallah’s name was Speranza, which means “hope” in Italian, so maybe their prayers were answered….

Twice Lucky

Two stunning kesubos, one from the NLI and one from the Braginsky collection, hang side by side. What is so unusual and unexpected is that two kesubos from two different collections both belonged to the same bride! Giuditta bas Daniel Valensin married David ben Joseph Franco in 1648, and then married Avraham ben Jacob Munion two years later. Was she widowed? Divorced? The answer is lost to history.

Cut n’ Paste

Spain, 1841. Yosef, son of Shmuel, marries Vittoria, daughter of Yosef Nachman. The border of this lovely kesubah and its central text look like an elaborate, lacy papercutting (of course, the document is written on parchment, not paper). As always, the first word of the text is the day of week of the wedding, which took place on Wednesday, “b’revi’i.” But the same word, “b’revi’i” is written again, in larger print, directly under the first one. Look closely and you’ll see that the text of this kesubah was actually cut-and-pasted onto another kesubah originally created 75 years before. In order not to damage the overall design, the word “b’revi’i” of the original had to be kept. Perhaps it was “recycled” to save money, or maybe it was a family heirloom.

Women of Power

Venice 1750. Jacob, son of David, marries Esther, daughter of Moses. We know from the kesubah that the chassan’s father, David Mendez, didn’t live to see his son under the chuppah. Sad, but not uncommon, in a place and time where the life expectancy was about 40 years. More unusual is that the chassan’s mother, Avigayil, appears in the tena’im as the guarantor of the conditions, hinting to the financial power of upper-class women in 18th-century Venice. She actually signs her name on the bottom of the kesubah.

Honor to the Crown

Several kesubos written during the long 19th-century reign of Queen Victoria include regal pictures celebrating the British Empire. A royal crown suggesting allegiance to the Queen tops the 1893 kesubah of Yitzchak ben Avraham and Georika bas Yehuda from the British colony of Gibraltar.

Indian Loyalty

The Kochi, India kesubah of 1852 of Yaakov ben Efraim haKohen and Ruchama bas Chaim, again topped by the royal crown, also indicates loyalty to the Queen, who decades later would be proclaimed Empress of India.

Tiger Tales

Bombay, 1842. The kesubah of Yaakov Chai and Mazal Tov is decorated with golden striped tigers, alluding to the Bengali tiger indigenous to the area, often used as a national symbol of India.

Fertility Fish

Calcutta, 1854. On the kesubah of Salih and Rebecca, Indian tigers share pride of place with a family of fish, a familiar Jewish theme representing fertility and a blessing for many children.

Unbroken Bonds

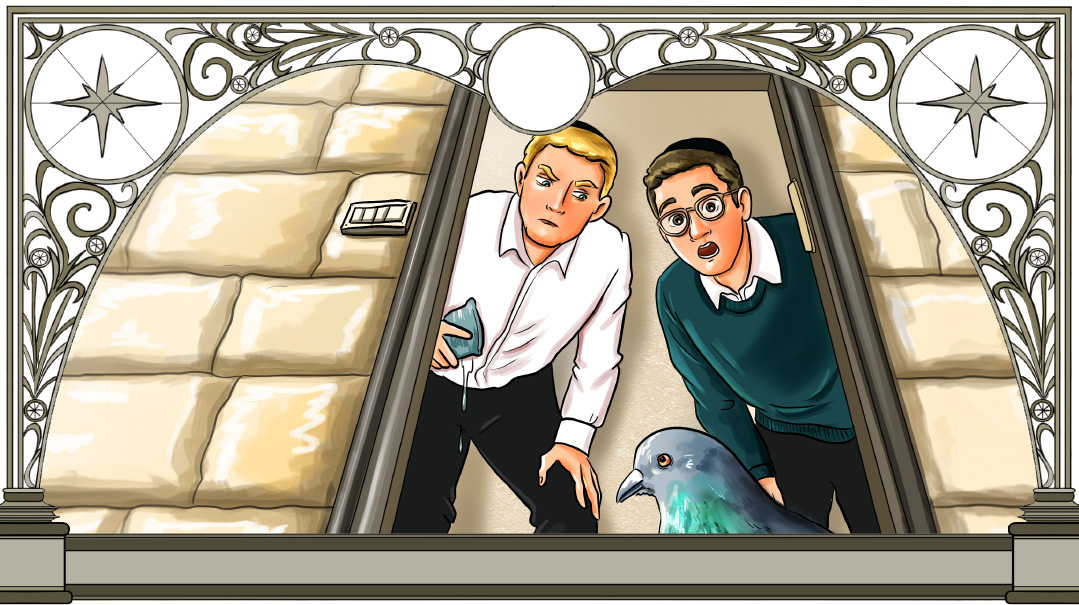

Rome, 1797. The marriage of Shem Tov ben Shem Tov and Rebecca bas Eliyahu. The exquisite kesubah is topped by an evocative picture: The chassan, dressed in blue, and the kallah, in pink, are attached by a chain looped around their necks. To our 21st-century eyes, a chain seems like a negative symbol — think criminals or slaves. But here the chain suggests something completely different. With the Latin words concordia maritale, marital harmony, floating around and between the couple, the chain symbolizes the unbroken bonds of marriage.

The clasp of the chain, so to speak, looks like a pomegranate, a rimon, holding the two together. In many cultures, this fruit symbolizes prosperity and fertility, an appropriate blessing for a new couple. Jews, of course, add the idea that each pomegranate has 613 seeds, suggesting the centrality of Torah and mitzvos in the life of the new family that the kesubah has established.

Printed or hand-illustrated, including just the text or framed by elaborate designs, simple or incredibly decorative, kesubos represent another chain — the chain of tradition upheld by the Jewish family, k’daas Moshe v’Yisrael.

And, as every kesubah, past and present, ends with, “v’hakol sharir v’kayam,” it’s all correct and confirmed, signed-and-sealed b’shaah tovah — Mazel Tov!

Magic Carpet

The NLI exhibit includes a number of entrancing kesubos from Eastern lands. Unlike their European counterparts, these kesubos don’t include any pictures of men or women, reflecting the Islamic ban on drawing human figures. Instead, they are filled with intricate geometric designs, arched, dome-like structures, and exuberant colors. Seen from a distance, they might be mistaken for elaborate Persian rugs, magic carpets to transport the young chosson and kallah to their new home.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1025)

Oops! We could not locate your form.