Streetlights and Shadows

| July 30, 2024Four centuries later, Jewish life in Vienna is coming full circle

Photos: MB Goldstein

Jewish Vienna saw its heyday after World War I — over ten percent of the population was Jewish, and while it was a magnet for secular culture, nearly every one of the two dozen districts had at least one shul. By 1938, 400 years of history and tradition literally went up in smoke, yet many of the old markers remain. And despite the horrors the city witnessed, Jewish life is again beginning to come around full circle

The Darker Side of Exile

Exactly 400 years since Jews were readmitted to Vienna by the Habsburg monarchs in 1624, we’re walking the streets of a city that has often served as an important center of Jewish life. The 20th century inaugurated a new heyday; when World War I forced Eastern European Jews to flee, many leaders and organizations found refuge in Vienna. In the 1920s, the city hosted Europe’s third-largest Jewish population: Roughly one out of every nine Viennese was Jewish, and 18 of the city’s 22 districts had at least one synagogue.

We’re going to look around the Second District, home to most of Vienna’s community today and a Jewish center since 1624.

The tram glides down Taborstrasse, a main thoroughfare, as pedestrians mill around cheerfully. Stores and apartment buildings line the streets, an urban milieu unrelieved by greenery. The occasional fully dressed Jewish passerby stands out among the crowd in the summer heat.

I’m apprehensive about my tour of Jewish Vienna. I love seeing where Yidden lived, hearing the stories of their lives, but something tells me that here we are about to see the darker side of our galus story. The Wall of Names memorial lists 65,000 Jews who were killed from all over Austria. The sidewalks I’m strolling on saw Jews pushed off, forced to kneel and scrub streets, taunted and beaten, and a glorious community was destroyed like a flourishing tree in sulphuric acid rain.

I leave my Holocaust ghosts and get back to the present. Historian and journalist Mrs. Rifka Junger, advisor at the Austrian Parliament, is walking with us from the busy junction of Taborstrasse along the line where the ghetto wall stood.

The first 14 Jewish houses in Vienna stood right here, in 1624. We pore over a historical map in the shadows of the surrounding 19th century buildings. The Tosafos Yom Tov served here as a rav in the original shul that used to stand between two of these buildings back in the 1620s, and he was later brought back from Prague to be imprisoned in Vienna. He mentions Vienna in his narrative of persecution entitled Megillas Eivah.

The ghetto grew fast, and in 1650, a large synagogue was built to serve some 1,500 members. But by 1670, Emperor Leopold I, a devout Catholic, had ascended the throne and expelled the Jews, who then numbered about 3,000 people. Their houses were given to gentiles.

And the shul? In front of us, flanked by statues of the emperor, stands the St. Leopold Catholic church, its position and structure identical to the synagogue outlined on the ancient map. Emperor Leopold had the shul destroyed, but it is said he left the foundations intact for a church dedicated to his “holy” personage. We scan the Latin engraving, which mentions that the Jews “left” the area, then a more modern plaque admitting the bald truth of expulsion.

The sidewalk offers a Stolperstein, a metal paving stone usually used to memorialize Holocaust victims, but here a monument to the exiled second Jewish community of Vienna, expelled in 1670. (See the sidebar for the story of the first community of Vienna).

Our next site, on Grosse Pfarrgasse, is far more modern and also special to Lubavitch — the building where the Rebbe Rashab and his son the Rebbe Rayatz lived for some months in 1903, when they came to Vienna to meet with psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. We look up at the second-story windows of the apartment that housed the Rebbe.

Hidden in Cellars

V

ienna and Bais Yaakov? We are 200 miles from Sarah Schenirer’s hometown of Krakow, the cradle of the girls’ educational movement, but Vienna holds an important place in Bais Yaakov lore, because the movement was conceived when Sarah Schenirer, among thousands who fled here from Poland and Galicia in the terror of World War I, was inspired by shiurim in Vienna by Rav Moshe David Flesch (as eloquently described by Dovi Safier and Yehuda Geberber in Mishpacha issue 989). Also, Rabbi Dr. Leo Deutschlander, the Agudas Yisrael representative who developed her vision into a pedagogical powerhouse, lived and worked in Vienna, and is buried in the city.

Right here on Leopoldsgasse, in this building, was the office of the Bais Yaakov school. We read the memorial plaque in German, visualizing those demure, dedicated young seminary girls of a century ago. Next to it, a plaque with more Jewish names, listing victims who lived in this building before they were deported to their deaths.

This is still a Jewish area today. Is it ironic that we feel safe and unthreatened on our walk, just another part of a cosmopolitan human tapestry?

Here, I learn something new — the Nazis never forced the Jews into a ghetto in Vienna. Instead, they were brought from all over the city and confined in crowded apartments — Sammelwohnungen, four or five families in one small apartment — until their time came to be deported east.

Right here, Rifka shows us an example, reading from a municipal plaque: The Nazis confiscated this apartment from its Jewish owners in 1939. Eighty-four people were kept here, until their deportation.

“A few streets away, you can see a whole block where 1,400 Jewish people were kept,” Rifka says.

On the corner of Leopoldsgasse, we pass a modern memorial praising non-Jewish Viennese who hid Jews from the Nazi murderers.

“Between 2,000 and 3,000 Jews were hidden in Vienna,” Rifka says. “They were often in cellars. I knew a woman who remembered being sent as a small child to bring food to Yidden hidden in cellars. On the very day Vienna was liberated by the Russians, we know that nine unfortunate Yidden were schlepped out of a cellar hideout and shot.”

Hiding Jews could incur death, so the righteous gentiles here were risking their lives daily. Yad Vashem has a list of 115 righteous Austrian gentiles who helped Jews, but it was a pretty poor showing out of a total population of ten million Austrians.

“When we grew up, we typically heard from the gentile neighbors, ‘Oh, our family was active in helping Jews during the war,’ or, ‘Our family didn’t see anything about what was happening to the Jewish community.’ That was what they said,” Rifka comments.

She remembers the day a Jewish man came to the door of their family’s apartment, saying he had lived there as a child. Since thousands of apartments and houses were confiscated (read: stolen) from their owners by the Nazis, this was commonplace.

The Stolpersteine cannot possibly list the names of all of the thousands upon thousands of Jewish victims. Instead, they pick out one name for each stone, with the date of birth, place of origin, sometimes profession, and where they were deported to. Many of these Jews did not even come from Vienna, but moved here to improve their lot in the early 20th century, seeking safety from World War I, or they were crowded in here when they were expelled from other kehillos by the Nazi sweep. My eye is searching for dates of birth in the 1930s. So many Jewish children! What did they go through here, and how much did they suffer?

Here, on Leopoldsgasse, was the bustling Agudah office. Agudas Yisrael became prominent in Vienna during World War I, when Eastern European Jews from Poland, Galicia, and other parts of the empire streamed here. It was a primary force in interwar Orthodoxy.

Between Us and the Lamppost

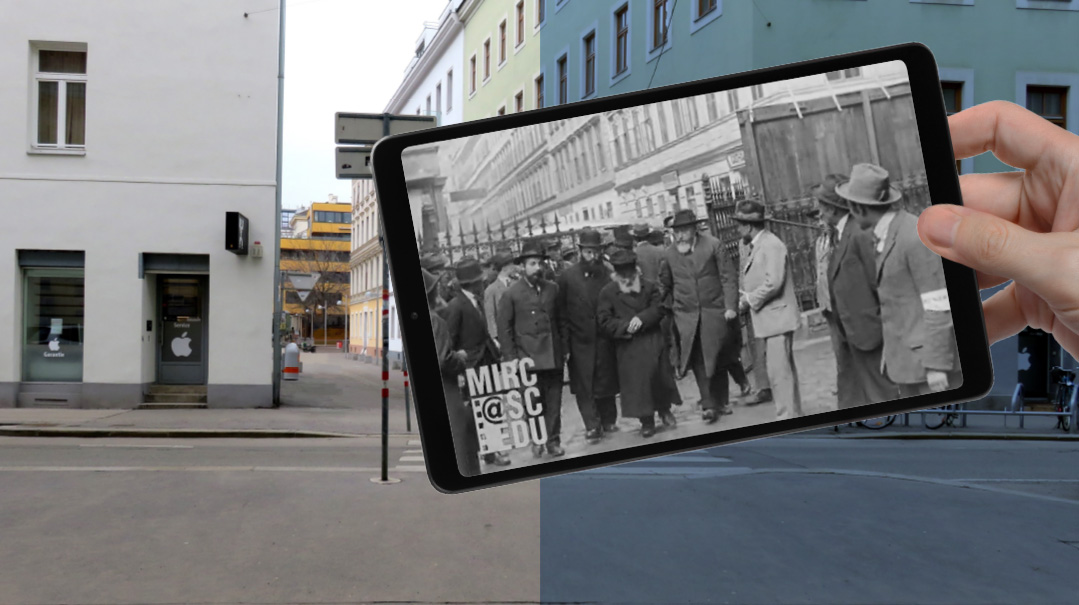

WE stop and look across the street. On her tablet, Rifka shows us how these buildings appeared 80 years ago. The yellow building wasn’t here. Instead, here stood the magnificent Poilisher shul, built by Jews from Galicia who came here for parnassah or medical opportunities from the 1890s onwards.

Including its shtiblach, Vienna had over 100 shuls in 1938. Of those, only the main shul, the Stadttempel, and the upstairs beis medrash of the Schiffschul still exist today.

I love to see old shuls, to imbibe the atmosphere of peace and prayer and finger the softness of the velvet paroches and polished wood, to imagine a rabbi inspiring the sanctuary filled for shofar or decked in white for Kol Nidrei. Here, though, there are no ancient shuls to experience. We are face-to-face with the vicious insanity of Hitler’s regime — in the fires of Kristallnacht, all was destroyed.

A metal pole looms above us, with the label “Polnische Schul,” and a QR code. When I look up, I see a Magen David, stark metal against the sky, and when I step away, it becomes an indistinguishable tangle.

Rifka explains the artistic commemorative efforts. “At the locations of 25 large shuls, they have put up these commemorative Magen Davids that become fluorescent lights at night. The shuls were destroyed in the November Pogroms of 1938 — nowadays in Austria it is not acceptable to use the [euphemistic] term Kristallnacht.”

No familiar feeling of warmth floods me at the commemoration of a burned-out shul. Only chilly remembrance hits as we look at the Magen David above and then at the building facades that so callously watched over the Churban.

Since Rifka grew up in Vienna, the consciousness of the Holocaust has always been there. In the background of her happy childhood as part of the rav’s large and lively family, there were her four grandparents who all survived Nazi concentration camps. There was an awareness, and a curiosity about what happened here, what the older people did to the Jews back then.

“As a child, sometimes I would think, unrealistically, What will we do if the Nazis come back? How will we hide, how will we save ourselves?”

This led her to pursue studies in history and her work in journalism, advocacy, and education.

As we turn onto Krummbaumgasse, Rifka tells us, “Every house on this street had some kind of Jewish presence before 1938. There were soup kitchens, kosher butchers, tzedakah organizations, shtiblach, shuls. You know, most chassidic courts had a shtibel in Vienna before the war. Here, on Krummbaumgasse, is the house where Rav Shmuel Wosner was born and lived.”

Krummbaumgasse meets Grosse Schiffgasse, where the famed Schiffschul stands. Rav Shlomo Zalman Spitzer, son-in-law of the Chasam Sofer, was the founding rav. Rav Spitzer did not succeed in getting permission from the authorities to establish a completely independent chareidi community, but the Schiffschul had a degree of autonomy — its own institutions. The main shul was destroyed. Today, the former administration building of the Schiffschul kehillah houses the Kahal Chassidim shul, while the upstairs beis medrash is one of two places in Vienna where a minyan functions in the same room as it did before the war.

Schooled in Horrors

WE

follow Rifka into a quiet square off a city street. She pauses and we look around. A colored sign announces that this is a Volksschule, or public school campus, and it’s now clearly deserted for summer vacation.

Rifka shows a picture on her tablet, taken on this exact spot: Two armed German soldiers, standing arrogantly. A wagon piled high with suitcases, linen, and bundles. Yidden securing the bundles.

“This building, and this one, and this one, and the one round the corner, are all a public school,” she says. “It was a public school before World War II, with many Jewish students and Jewish teachers. They were all removed from their posts and the children were thrown out of school… and then, in 1941, the students here were sent to a different location, because this was turned into a Sammellager from 1941 to 1943. This is where they brought the Yidden from all the apartments I showed you before. From here, they were taken to the train station. There was a gate there — and the people were locked in, most of them in this building, under terrible conditions.”

“In the middle of the city, right here?” I confirm. Because could anything be more public than a public school building in the middle of a residential district?

“Yes.”

The building had no indoor washrooms, and access to the outhouse in the courtyard was strictly controlled, leading to foul odor and disease indoors. The prisoners’ accounts mention that both rats and lice afflicted them.

Rifka shows us the plaque on the wall. It’s unimpressive and so understated that if you wouldn’t know it was here, you’d never notice it. It reads, translated from German: “In memory of the 40,000 Jewish citizens who in the time between October 1941 to March 1943 were kept by the Gestapo in this part of the building and from here were deported to the extermination camps. Never Forget.”

The picture of the Yidden loading the packages that they were supposedly allowed to take with them hits us squarely between the eyes. The pekelach contained all that was dear to them — that hadn’t yet been plundered — and all they thought they’d need. Which was, of course, a double farce: It was about to be plundered, and they were not going to need anything, because they were about to be murdered.

In total, just over 48,000 Yidden were deported from Vienna. (Many others managed to flee the country before the borders slammed shut in 1941, some only for the Nazi beast to catch them later.) So the overwhelming majority of those left the city from this spot. Another plaque, adjacent to Stolpersteine: “To remember the roughly 45,000 Jewish people who spent their last days before deportation in the most horrific circumstances in this Sammellager.”

Stolpersteine, more names. Walter Hollander, born in 1936. So he was five years old when the terror tore his world and took his life.

Another form of remembrance is in the black words printed across the sidewalk, grabbing my attention: “Eines nachts, geht meine mutter mit mir… [One night, my mother took me out to use the outhouse. We saw that the gate was slightly ajar. There was my most precious possession, my bicycle. We took our chance and we stole outside…]”

This is the story of one Jewish mother and her little boy, who were saved from the fate of thousands by the bike he had brought along, and the carelessness of one Nazi guard who didn’t lock the gates properly.

Around the corner, outside another entrance to the public school, the plaque is more specific. It memorializes “students and teachers taunted by their fellows, hit, and spat at.”

I ask Rifka if she was ever taunted, hit, or spat at, many decades post Holocaust here in Vienna. Well, yes. Once, several years ago, outside her house, walking with her oldest son, then aged six or seven, an Austrian woman walked by, commented “du kleiner Rabbiner” —and slapped Rifka across her face.

Every Jewish institution here has an Austrian police presence outside, and on Shabbos, they have Jewish security guards, too.

We’re now on Lilienbrunngasse, one of the most heimish streets in Vienna today. The apartment buildings house several frum families, and there’s the Ohel Moshe minyan, and a lovely bakery, also named Ohel.

Here we encounter some Israeli tourists taking advantage of the kosher eateries in the area. The community has a well-developed kosher food scene for its size, with a handful of kosher cafés and restaurants, as well as a welcoming ice-cream store. Many of the restaurants are owned by Bucharian Jews, who make up roughly a third of the Jewish community in Vienna today.

Under Ottoman Protection

WE pass a stone in memory of the Belz shtibel. Rifka’s father, Rav Avrohom Yonah Schwartz, rav of Kehal Chassidim, was a close talmid of Rav Henoch Padwa, and heard from him the story of how as a young man he hid in a doorway here to escape Gestapo officers. Since the shtibel was inside an apartment building, the Nazi mob only destroyed the interior, unwilling to burn down a perfectly good building.

We pass the LaMehadrin kosher mini-market, and chat about the Jewish schooling available in Vienna. The kehillah has two boys’ elementary yeshivos and one girls’ school, in addition to a Chabad school system and a nonreligious Jewish school. The largest class of Bais Yaakov girls since World War II just graduated here, a total of 25 girls.

Austrians speak German, although it sounds slightly different from that spoken in Germany. In fact, Yiddish words have been absorbed in the local dialect over the centuries, so that non-Jews use words like tachlis, mazel, mishpuche, and metziah.

We pass the contemporary Viener yeshivah and the Machzikei Hadas shul, also guarded. In contrast to some buildings with decorative moldings and charming facades, others are drab and modernist. Apparently, the Allied bombing campaign of World War II caused damage to many buildings here, and when they were rebuilt, they were simplified.

Soon, we’re at another memorial lamppost with a Magen David light on the location of the Türkischer Tempel, a beautiful and ornate structure built in 1885. This represents the history of Sephardic Jews in the city. In 1683, the powerful Ottoman Empire laid siege to Vienna. Austria narrowly avoided surrender, and the cease-fire document stipulated that any citizen of the Ottoman Empire who chose to settle in Austria would remain under the protection of the Sultan. When Turkish Jews trickled in to do business, the Austrians therefore had no choice but to allow them full rights to establish a community. Ironically, this was at a time when Ashkenazi Jews had been expelled, and only single families dwelled in the city.

Of course, it was destroyed on November 10, 1938, and no survivors of this Turkish Sephardic community returned to Vienna from the death camps. Although Jewish representatives were given back the property, they saw no future need for a large synagogue, and sold the land to the government, who built subsidized apartments for affordable housing.

Culture Magnet

S

tanding proudly on a corner, the recently revived Nestroyhof Hamakom Theater represents another side of Jewish history here. A century ago, Vienna was the place to which so many young Jewish people from Galicia flocked when they left Yiddishkeit behind and followed their dreams to make it big in academia, medicine, or any other modern profession. This Hamakom, a Jewish theater, was a magnet for thousands of youths who dreamed of fame and wanted to star on stage. Prominent throughout Viennese cultural bastions, Jewish talent shone, while assimilation snatched countless souls — until the rude awakening of anti-Semitism ferreted out the Jews from their chosen ivory towers.

“So many prominent Austrians were Jewish,” Rifky confirms. “In politics, in science, in medicine, in music, the Jews were eminent and successful. Arthur Schnitzler, the playwright and novelist, composer Gustav Mahler, and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud were all children of Yidden who emigrated here from Hungary or Galicia.”

We walk down Tempelgasse, a narrow side street, closely packed with cars. Right in front of us once stood Tempelgasse’s massive 2,000-seat shul, the Leopoldstädter Tempel, largest in Vienna, and one of the largest shuls in Europe. It held the archives of the community and was home to a rabbinical seminary. Apartment buildings have been built over the once-hallowed ground, and now the four replica pillars at the front are under repair. The temple had Orthodox rabbis at the pulpit, but veered toward modernity; for example, the bimah was at the front of the shul, rather than in the traditional center. Rifka shows us a picture of the beautiful shul, and then another of its wanton destruction.

Today, the surviving left wing of the building has been restored to house the Agudas Yisrael shul, a mikveh, a cheder, and a Jewish kindergarten.

Right nearby is a Sephardic Jewish center, with one Bucharian synagogue and one Georgian synagogue. Austria has long been a hub for Jewish immigrants from Hungary and the former USSR. For example, more than 18,000 Hungarian Jews passed through after the Hungarian Uprising in 1956. The vast majority move on to the United States, but a few settle here. In general, our hosts here tell us, postwar frum Vienna always felt like a stopover, rather than a destination. Over the past decade, though, it has experienced some growth, with more families opting to settle here by choice.

The Knessiah Gedolah

Zirkusgasse (Circus Street) seems an unlikely spot for a momentous location. There are some boringly staid apartment blocks with a gigantic mailbox, lightly sprinkled with some of the graffiti we’ve seen all over the place. But we stop after Number 42, where Number 44 Zirkusgasse used to be.

In Elul, it will be 101 years since the first Knessiah Gedolah, and we’re now at its location, the site where great men gathered to debate and direct Klal Yisrael, the site where Rav Meir Shapiro presented his idea of a daily daf learned by all Klal Yisrael on a unified schedule.

The Knessiah Gedolah was initially planned for 1914, but was canceled due to the outbreak of World War I. That great war brought a population of 200,000 Jews to Vienna. Although there was some fanfare about the recent centenary, it wasn’t possible to organize any event in the same auditorium, simply because it no longer exists. What the venue was, Rifka’s historical pictures show, was a circus ring. The inside held a complete circle of seating, but during the Knessiah Gedolah, sheets were hung to partition some of the seats for women, and a banner declared “Sha’alu Sholom Yerushalayim.”

“You know the famous film of the Chofetz Chaim?” Rifka says, indicating a photo. “So the camera was held back here, and the gate the Chofetz Chaim was walking through was right here, where we are standing. The building opposite is the same building, the corner is still there as it was, just the façade is now flat.”

She rewinds until we see Rav Perlmutter, the chief rabbi of Warsaw, in a top hat, followed by the Chortkover Rebbe. The Rebbe, who lived just around a corner, arrived on foot, holding an umbrella. Then the Chofetz Chaim appears, and Mr. Wolf Pappenheim, head of Agudah in Vienna, blocks the camera, as he knew the Chofetz Chaim did not want to be photographed.

Taking in the street view that those distinguished guests must have seen, we walk slowly toward the dwelling of Rav Yisrael Chortkover. While many chassidic rebbes fled to Vienna during World War I, several rebbes of the Ruzhiner dynasty, most famously the Chortkover, remained here, and are buried in the city’s mammoth Jewish cemetery.

The Rebbe was so famous, that even gentiles called him the Wunder Rabbiner. The Kopyczynitzer Rebbe, his cousin, also lived and had a shtibel on a side street very close by. We move on, stand in the Rabbiner Friedmann Square, now crowded with outdoor café tables. Vienna’s streets are crowded and cosmopolitan, and the story goes that the Rebbe was once sitting on a bench when a woman sat down next to him. He waited a moment before consulting his pocket watch, remarking that it was late, and moving on.

A plaque outside the Chortkover’s residence on Heinestrasse 35 memorializes the Rebbe and the many “devout Jews and Jewesses who gathered here from all over the world.” The levayah, which left from the building we are standing under, turned the wide boulevard black with hundreds of mourners gathering for the Rebbe’s final journey in Kislev 1933.

We’ve touched the heart of Jewish history of Vienna here in the Second District, although in its heyday, there were shuls and Jews all over the city. Sarah Schenirer, for example, writes in her memoirs that she desired to daven in the Schiffschul on Shabbos, for she had heard of it, but was staying too far away, in another district.

Yet this Second District, Leopoldstadt, and the adjacent 20th District were the most densely inhabited by Jews. In fact, bordered by the Danube Canal and Danube River, the two districts were known as the Mazzesinsel [“Matzos Island”] for their Jewish character. It’s incredible that despite the horrors the city has witnessed, Yidden continue to live intensely Jewish lives here, learning and davening, raising families and taking care of each other, a clear sign that nothing can erode that eternal promise.

A History of Light and Dark

IN the Judenplatz in the First District, we see the traces of the first Jewish community in Vienna, which existed for 200 years in the Middle Ages. A Jewish financial advisor to Duke Leopold V by the name of “Shlom the Mintmaster” is documented to have lived and even owned real estate and built a private synagogue in the city center in 1196. Shlom and his family were murdered by Crusaders. In the 13th century, the community lived around the Judenplatz, where they had the Judenspital [Jewish hospital], the Judenschule [Jewish school], the bathhouse and the house of the rabbi.

The community became one of the most important in medieval Europe, partly because of the presence of its rav, Yitzchak ben Moshe — known today as the Ohr Zarua.

Under the Jewish Museum in the Judenplatz, we view the excavation of this ancient shul. Interestingly, it was only discovered by modern archaeologists in the 1990s, during the building of a Holocaust memorial in the Judenplatz square. The areas of the aron kodesh and the bimah can be clearly seen.

This first community was cruelly destroyed in the “Vienna gezeirah” of 1420-1421, when Duke Albrecht V ordered Jews’ robbery, expulsion, and murder. On March 12, 1421, he issued an edict forbidding Jews from settling in Austria for all time.

However, just 60 to 80 years later, pragmatism won out, and individual Jews received permits to settle for specific reasons. In the 1620s, Rav Yom Tov Lipman Heller, the Tosafos Yom Tov, who served as av beis din of Vienna, approached Emperor Ferdinand III for permission to establish a community. Permission was granted, but the Jews were to live outside the city limits. At the time, only the First District was the capital, and the area outside, a swampland. The Jews built homes in the ghetto area that is now Leopoldstadt, the Second District.

The Jewish museum features excellent exhibitions on the medieval Jewish community, including names of members in their own script, proving the exceptional literacy of the Jews at a time when many adults across Europe could only authenticate documents with wax.

Other sections are devoted to Holocaust exhibits, including a striking one titled Raub! Theft! Which showcases the property systematically stolen from Austrian Jews by the Nazis. The museums of Vienna were found to have been complicit in the Nazi war crimes, incorporating in their collections items looted — or shall we say Aryanized? — between 1938 and 1945. Since Viennese Jews had to register their wealth and were deprived of their livelihoods, some were blackmailed into selling their assets at rock-bottom prices. Neighbors stole, the Gestapo seized, and the city authorities and museums looted to their hearts’ content. We view a very partial list of addresses of Jewish homes that were summarily wrested from their owners. Theft indeed.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1022)

Oops! We could not locate your form.