Tales of the Talmud: Tragedies and Triumphs

| June 9, 2024The Reading Room at the National Library of Israel (NLI) is home to innumerable sets of Gemaras

The Reading Room at the National Library of Israel (NLI), three soaring stories covered by a massive domed skylight, has been likened to an immense well. The building’s lowest level contains a large, circular shelf designed for oversized books, home to the library’s innumerable sets of Gemaras — our nation’s life source stored there like water deep in the heart of a well.

The Past Is Prologue

After the Churban, when Klal Yisrael began their long exile, our Sages realized that Torah shebe’al peh (oral halachic transmission) was at risk, and halachah needed to be written to avoid getting lost. Rabi Yehuda Hanasi compiled the Mishnah around the year 200; 300 years later, Ravina and Rav Ashi compiled the Talmud.

Few handwritten manuscripts remain, for various reasons. For starters, Gemaras weren’t written for display; rather they were designed for daily use. A town might have only a few masechtos, shared by all, and however durable the parchment, constant use took its toll.

Another — tragic — reason we have few surviving copies: the Talmud was viewed as an existential threat to the reigning church. Christian leadership would frequently stage biased “debates” and “trials” of the Talmud, designed to prove which religion was the truth, and most, if not all, copies of the Talmud would be destroyed or heavily censored.

Photos: Bavarian State Library, the National Library of Israel.

“Ktiv” Project, the National Library of Israel

The Lone Survivor

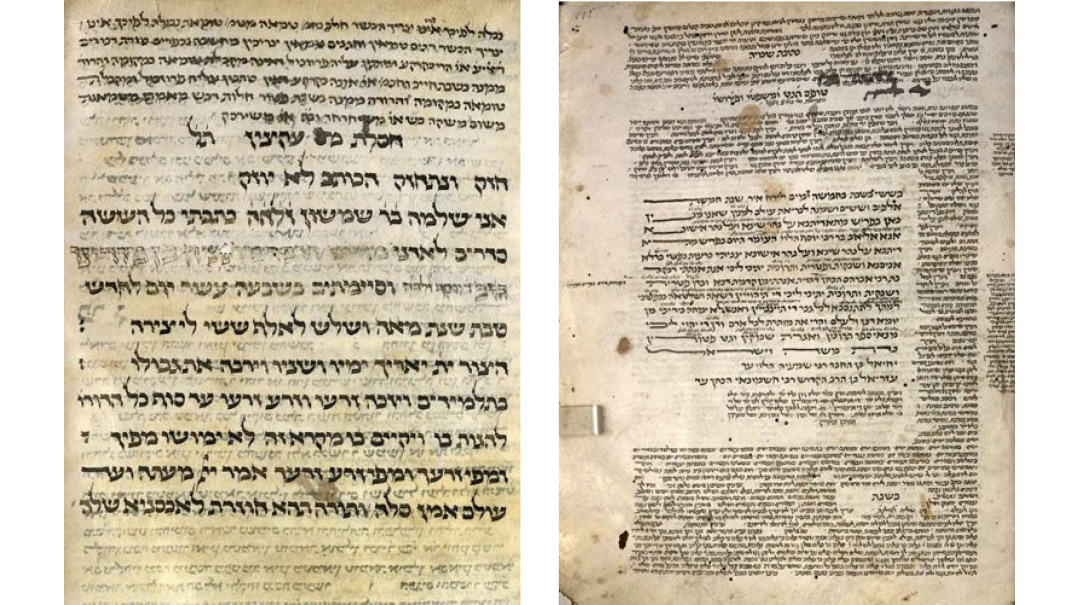

Munich 95 | 1342

There is one known complete handwritten Talmud, a rare miracle with the unassuming name: Munich 95, named for a cataloging term at the Bavarian State Library, its current home.

Written in 1342 by the sofer Shlomo ben Shimshon (who often decorated the name Shlomo when it appeared in the text), this colossal, handwritten work is comprised of 577 painstakingly detailed pages, with all 37 tractates of the Talmud text written in smaller print around the Mishnah being discussed, 62 tractates of Mishnah in all. It also contains various baraisas, a section with 40 halachic contract samples, and even poetry; an anthology of Torah in one leatherbound edition.

This safrus marvel is crafted on the thinnest parchment, likely from newborn goat’s skin, with microscopic lettering measuring one-and-a-half millimeters high (compare that to Times New Roman size 12 font, which is over 3 millimeters high), legible due to the invention of glasses in Italy several decades earlier.

The 14th century was a dangerous time for the French Jews, who suffered expulsions, forced conversions, and other atrocities. The Chief Rabbi of Paris, Yochanan ben Mattisyahu, owned the Munich 95, but the church confiscated it and imprisoned him under the charges of using the Talmud to spread anti-Christian ideas. Despite the danger, Rav Yochanan wrote letters from his prison cell, urging others to create more copies of the Talmud to replace those that were destroyed. He was eventually released from prison after he paid 3,000 florins and agreed to erase anything “anti-Christian” from the Talmud. Close examination of the Munich 95 manuscript does reveal some erased lines, but Rav Yochanan’s defense allowed this copy to survive for centuries.

While the NLI doesn’t have the physical Munich 95 print, it does have online access and a facsimile.

Oops! We could not locate your form.