One Fate

| May 7, 2024Between the barracks in Auschwitz and the once-peaceful pathways of the towns in the Gaza Envelope, will Jewish life ever go back to safe mode?

This past October, I was scheduled to leave for Poland the day after Simchas Torah with a group of 50 people who would be participating in an “unknown Holocaust” tour. Most members of the group had already done the classic route: Warsaw, Majdanek, Krakow, and Auschwitz, but now, they wanted to see things beneath the surface.

The program included Jewish Prague and the nearby Theresienstadt camp: the terrifying fortress, the deceptive German programs, and the hidden shul that is concealed between the lanes of the camp. In Krakow, my plan was to lead the group to lesser-known places, including the site of the notorious Plaszow work camp, which today bears silent testimony to the story that is hidden under its green grass and lush trees.

We also planned to visit the “hidden Auschwitz,” a massive city most people who visit Birkenau and only come to the area close to the gate of the camp never see. We were to start at the “Juden ramp” on the outskirts of the city of Oswiecim, and we’d also get to Crematoria 5, the notorious “villa” where the first 100,000 people were murdered in Auschwitz, the fire pits, the disinfecting room, and more.

Our itinerary was all planned.

And then, on Simchas Torah, the Jewish world turned over.

On Motzaei Simchas Torah, we realized that we were not going to visit the unknown parts of Auschwitz — because Auschwitz suddenly seemed very close indeed.

Even if we had wanted to travel, the skies were closed — arrivals and departures were canceled, and in any case, no one was in the mood for a trip.

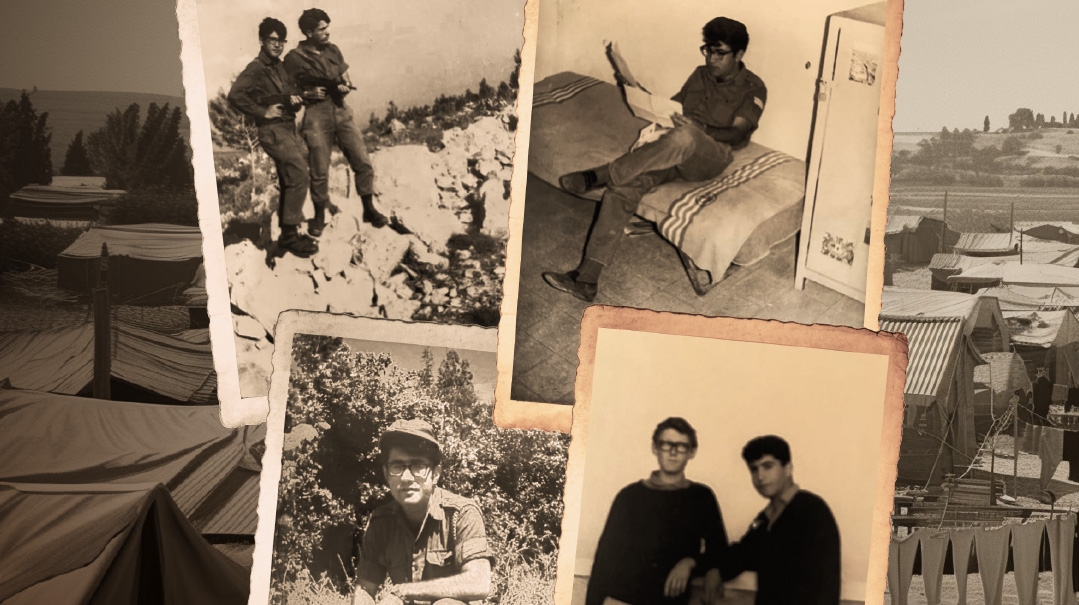

Since then, during this past winter, I’ve had the opportunity to take a few groups to visit Poland (most of them from abroad), but the terror of October 7 and the subsequent and shocking anti-Jewish fervor gave us a different type of connection: the feeling of continuity and the shared fate with the Jews of a decimated Europe.

Anti-Semitism has always existed. There have always been troubles for the Jewish People. Yet why has the decree of Simchas Torah somehow felt distinct from other troubles Am Yisrael has endured in the past? Is there really a difference between Auschwitz and the Gaza Envelope?

Committed to the Journey

Those of us who’ve grown up in the past half century have a pervading sense that the troubles are behind us. Our nation suffered in the past — there were the Crusades, the Inquisition, the Cossacks, the Nazis, the Communists, and the Cantonists.

But we, the members of this generation, were sent on early retirement by Hashem. The final Geulah has not yet arrived, Mashiach has not yet put in an appearance, but he is just behind the threshold. Stories of the Holocaust are like eating maror on Seder night: to remember that once, before things were so good for us, there was a time when we suffered.

And in one minute, it was all upended. They meant us, there was no mistake. Am Yisrael is a nation that struggles. From the beginning of time, we set out on the path with the knowledge that it would not be simple to be Jews, yet we committed to the journey. That was true of previous generations and it is true in our pampered, spoiled generation as well. At the Bris bein Habesarim, HaKadosh Baruch Hu showed Avraham Avinu all the exiles his descendants would have to endure. He was enveloped in deep darkness and fear, and he saw all that would come upon his children — Bavel, Persia, Greece, and Rome. HaKadosh Baruch Hu took Avraham Avinu to Bergen Belsen and to Buchenwald.

And today I know that Hashem also took Avraham Avinu to Be’eri and to Nir Oz, and said to him, “Look what the offspring of your wild son will do to the offspring of the son that you loved.” Avraham Avinu felt our pain, and chose it despite everything.

NO COMPARISON? The burned-out shell of a house in Be’eri (left); the ruins of a Berlin shul after Kristallnacht

Tranquility in Auschwitz

Auschwitz of today is inviting, dotted with wooden huts surrounded by grass. As chilling as this description sounds, it’s a friendly tourist site where visitors walk around, take pictures, and every so often stop to refresh themselves with a drink, make a phone call, take some selfies, and send pictures.

It’s an important and significant tour for every non-Jew to take, and certainly for every Jew. But today, most of the tourists are no longer aghast. They see, they are impressed, they learn, they even get emotional, but they don’t fall apart. In Be’eri, Nir Oz, and Kfar Azah, the Holocaust still exists — scorched, bloodied, and weeping. There’s nowhere to go without being horrified.

In the winter, I was taken on this modern Holocaust tour. On Thursday I was in the Majdanek camp on the outskirts of Lublin, Poland, which has become an organized, preserved tourist site. The following Tuesday I was in the Gaza Envelope region. The fire, the soot, the bullet holes, the shrapnel from the grenades, the notations made by ZAKA personnel on the walls with instructions for the next ones who came. The fire is fresh — its smell still lingers in the air.

In one corner of a house, I see a large pile of shattered crockery. I realize that this was the cabinet with the dishes; the closet burned while the dishes shattered to the floor. In the middle of the tour, I wanted to breathe for a minute. I entered the little shul in Kfar Azah (yes, there actually is a shul in this secular community) to say a few chapters of Tehillim. At the entrance there was a big sign, relating that the shul was donated by the Bibas family. The image of the little redheads — the youngest hostages, just babies — pop into my mind yet again.

Next to one burned-out home sits a man. I wish him a good morning.

He says, “Halevai, I wish.” He motions to the house and says, “Go in. This is where my daughter was murdered.”

It’s the father of Sivan Alkabetz Hy”d, and he’s turned her small house into a macabre commemoration museum.

What can I tell you? Going to Auschwitz today is easier.

The Poles don’t have tourist sites. No Big Ben or Eiffel Tower. They have the camps and they make sure to keep them clean, elegant, and inviting. For the Poles, it’s a rather lucrative operation as well, to be honest.

I don’t know what will become of the burnt-out communities in the Gaza Envelope region. The residents are divided in their views. Not all of them want to turn their towns into Holocaust museums. When I was in Be’eri, I saw the tractors flattening and clearing the inner neighborhood that was devastated by the attack. The outer neighborhood was still standing as before.

Nir Shani, a survivor of the pogrom, hosted me in his burned-out house.

“I was here,” he said, pointing to what was the reinforced room. “Come and see where the terrorists were.” He took me up to the roof and showed me a mound of bullet casings. “They barricaded themselves over my head and shot for eight hours while I held the door handle from the inside.”

I asked him gently how he emerged normal from this nightmare.

“I didn’t have time to think,” he replied. “When I came out, I had a mission. My 16-year-old son Amit was taken captive to Gaza, and I spent every waking hour trying to get him out.”

Amit, who’d been living in another house on the kibbutz with his mother and three siblings after his parents divorced, was captured and hauled off to Gaza when terrorists broke their way into the family’s safe room (the rest of his family miraculously survived the onslaught). He was released on November 29.

We are used to hearing tragic stories of exile and oppression of our nation in the past tense; now those stories are in the present. Stories that don’t yet have a happy ending, that arouse everyone to daven for that ending to come.

The Greatest Brutality

For years, we took great care not to use the term “Holocaust” with anything else aside for the destruction of European Jewry. The message was: There was only one Holocaust, to one nation, by one nation, one time. We vehemently objected when anyone referred to a “Palestinian holocaust.” Even someone who tried to call Kosovo or the Aleppo bombings a “holocaust” encountered objections that there was absolutely no comparison — and we were right to object.

Here in Israel as well, every demonstrator who wanted to horrify his listeners by using terms such as Nazi, Hitler, and the like was met with firm opposition for cheapening the Holocaust. How much more so did we condemn the narrow-minded agitators who screamed “Nazi” at a policeman, or at a bus driver who didn’t open the door when it had pulled away from the bus stop?

Since Simchas Torah, many of the Israeli spokespeople who wanted to shake up an apathetic world have spoken about the “Nazi Hamas terrorists” and the “Holocaust of October 7.” True, the savage murder of 1,200 Jews on one day is heinous and horrific, but during the Holocaust, there were long stretches during which ten times as many Jews were being murdered every single day. For half a year, beginning in the summer of 1941, tens of thousands of Jews in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania were shot dead daily. In the winter of 1942, during Operation Rheinhard, tens of thousands of Polish Jews were daily murdered in the camps. In the summer of 1944, tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews were killed daily in Auschwitz.

While the numbers don’t compare, what is true is that the sheer animalistic brutality that the Ishmaelites displayed far surpassed that of the Nazis. The Nazis were “cultured” animals, promoting “cultured murder.” They constantly upgraded their methods to murder without contact: from pistol shootings to automatic weapons, from machines that caused people to choke to death to poisoning with Zyklon-B gas. And if a human hand was necessary, they made sure that that human would be a wretched Jew from the Sonnderkommando, who was tasked with separating the holy corpses, removing the gold teeth from their mouths, cutting their hair so that it could be used for German industries, loading the bodies into furnaces, and gathering the ashes to be buried around the camp or dumped into the Vistula River.

The Nazis just poured the can with the poison. The rest of the dirty work was left for others. When Adolf Eichmann yemach shemo observed Nazi soldiers in the Ukraine murdering Jews by shooting them, he was horrified.

“It’s not fitting for Reich soldiers to kill this way,” he stated.

In fact, Heimlich Himmler ordered the SS murderers to be provided with an unlimited supply of alcohol so that their senses would be dulled when they carried out the murders.

With Hamas, the world was aghast to see the pure, unadulterated brutality and cruelty that the terrorists gleefully filmed — scenes that were heinous and macabre in a way that is virtually unmatched. Those who were shown viewings of the horrific sights — Jews and non-Jews, both righteous among the nations and anti-Semites — fainted, vomited, or fled because their souls couldn’t withstand the scenes. Even I, who have taken tours of the death camps and videoed Holocaust documentation countless times, could not look. At a viewing, I held on for 20 seconds, and then I stopped.

An anguished Yid asked the Klausenburger Rebbe while in Auschwitz, “Rebbe, do you still say Atah bechartanu?”

And the Rebbe replied, “Certainly! Now I say it with even greater kavanah, because if I had not been chosen to be a Jew, I might have been a murderous German. I prefer to be a suffering Jew than a cruel non-Jew.”

Eighty years have passed.

Mrs. Aviva Segal of Kfar Azah is sitting in a hotel in Jerusalem. The Kesher Yehudi organization has arranged a Shabbos for the families of the hostages, and as a merit to their loved ones, they will keep the first Shabbos of their lives. Mrs. Segal came because her husband is a hostage in Gaza (Shmuel Keith ben Gladys Segal, for a yeshuah and hatzlachah. Over Pesach, Hamas broadcast a video of him in captivity). She, too, was held hostage in Gaza for six weeks.

This kibbutznik who lived for the ideologies of coexistence and equality tells everyone, “After I saw how they trampled us and acted so brutally — now I say, what a miracle that I’m a Jew.”

VERY CLOSE INDEED Rabbi Goldwasser at the devastation in Kibbutz Be’eri after October 7

Modest Murderers

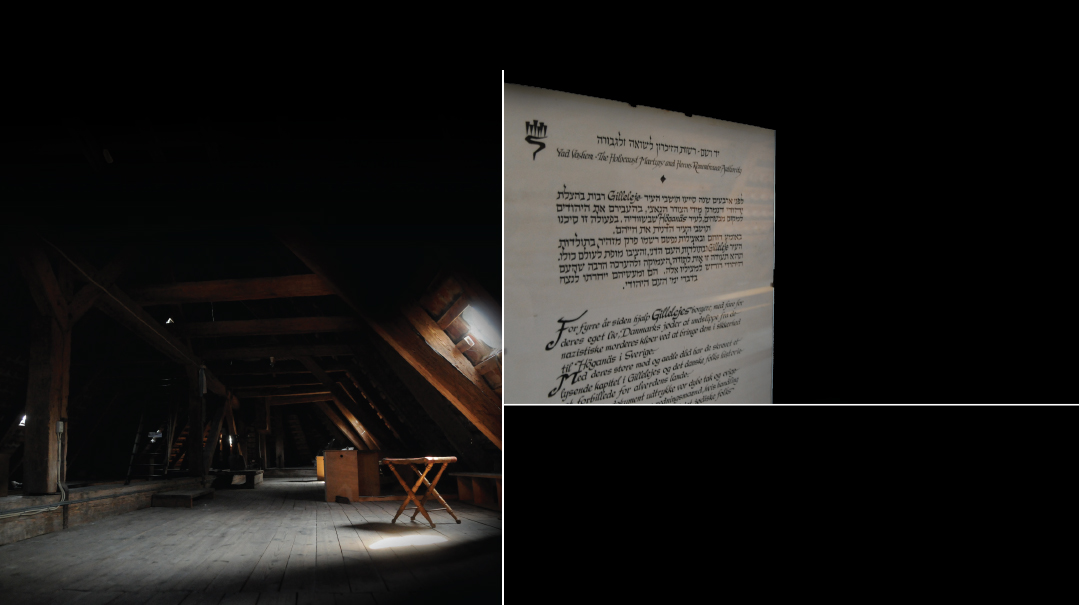

The Nazis maintained confidentiality and secrecy, as if on some level, they were ashamed of what they were doing.

Himmler tried to infuse the Gestapo with motivation, telling them, “You are engaged in a very important task on behalf of the entire world, but the world will not dare thank you for it.”

Every camp that was discovered, or where an uprising broke out, was completely destroyed by the Nazis. Right after the Treblinka uprising, they turned the whole camp into a botanical garden. Archaeological digs at Sobibor and Treblinka have uncovered hidden ashes in the ground only three feet down.

Hamas terrorists, in contrast, are proud of their deeds. Throughout their grisly rampage, they filmed and photographed it all and sent out pictures and videos. As far as they are concerned, it was all a good reason for a party.

The Nazis forbade photos except for those in their official archives. The entire area around the camps was a closed military zone, and there were hardly any pictures. In fact, of the murder of six million, there are just a few film clips of a few seconds each, documenting the killings of a handful of Jews. The pictures of liberation day, when the Allied soldiers came accompanied by military photographers, were those that documented the mounds of confiscated possessions, the half-dead musselmen, the mass graves, the piles of bodies and bones.

On Simchas Torah, it was the opposite. The murderers disseminated endless footage, photos, and clips of the pogrom, from the Jewish towns being destroyed to the rabid Gaza rioters exulting around the hostages. But from the minute the security forces managed to gain control over the situation, b’chasdei Shamayim, the censorship started. Am Yisrael, with sensitivity and refinement, made sure not to publicize the horrific images that depicted the Gaza Envelope region after the murder rampage.

Finding G-d in Captivity

Over the years, I’ve gotten used to questions like, “You describe the Holocaust as a time of great kiddush Hashem, but what about all those Jews who sold their souls to the devil or became like animals for an extra crust of bread?”

I don’t deny that there were many who couldn’t make the leap when the tests were so great, but I believe it was outweighed by those who, instead of cavorting with the devil, became angels, passing on a legacy of mesirus nefesh and a handbook for the rest of us to learn from their deeds.

And then came the pogrom of October 7.

It’s no secret that the gezeirah this time was cast primarily upon Jews who are not Torah observant. I initially thought that this time, there wouldn’t be stories of kiddush Hashem, that we wouldn’t hear the dialogue of Atah bechartanu.

I was wrong.

I spent Shabbos with families of the hostages on two occasions, and I also joined them for an arranged Purim seudah. I thought I was coming to give chizuk, but in the end, it was I who came out feeling strengthened, and with a greater sense of personal obligation.

Agam bas Meirav Berger is being held captive in Gaza. She’s a 19-year-old girl who was kidnapped from the Nachal Oz military base. She’s not a Bais Yaakov graduate, nor did she grow up in Meah Shearim. She fell captive on Simchas Torah, and it was in those horrid tunnels that she took upon herself the yoke of Torah and mitzvos. She davens to the best of her ability and knowledge, she makes brachos on the bit of food that she gets, and above all, she’s taken upon herself Shabbos observance. Hostages who were with her in two different hideouts and were subsequently released all gave the same report: Agam took upon herself to keep Shabbos, and she spends every Friday praying that her captors will not make her desecrate the holy day.

When Hamas terrorists forced her into serving them in their homes, she refused to light fires and cook for them on Shabbos.

“I can’t bring myself to think of the violence and cruelty of her captors,” says her mother, Meirav Berger. “But Agam is the strongest person I know, and is choosing to lean on her faith and lifting up those around her.”

Agam’s mesirus nefesh has generated great chizuk in her family’s neighborhood in Holon. Her parents established a shul in her room, and it quickly became far too small; now the mispallelim gather in the courtyard, and the minyan is growing from week to week.

Her father says, “She won’t believe what is waiting for her here when she gets back.”

B’ezras Hashem, may it be very soon, and physically and emotionally intact.

Out of the Ashes

Today’s terrorists have come for jihad — holy war — against the modern world, the Western world, against liberal America and the secular state of Israel — ostensibly in the name of religion and faith. But theirs is murder and brutality.

And what is Am Yisrael’s response? Mesirus nefesh for other Jews.

The stories we know of kiddush Hashem during the Holocaust were often attributed to rabbanim, rebbes, and many, many simple Jews of faith. Yet so many of the recent heartrending stories of mesirus nefesh are about Jews who are not considered Torah observant, some even defiantly so, yet who risked their lives to save others.

Many of the murdered, both in the towns, yishuvim, and from the security forces, were killed because they tried to save other Jews. They could have remained home, far from the danger, or could have run and saved themselves, but they jumped into the inferno and gave up their lives for the sake of saving Jews who they did not even know.

There are currently four security guards from the Nova festival in captivity: Bar Avraham ben Julie Cooperstein, Rom ben Tamar Braslavsky, and Eitan Avraham ben Efrat Mor. (Elyakim Shlomo Libman Hy”d, who spent hours tending to the injured, was thought to have been taken into captivity, but his body was identified several days ago — he was killed on October 7 while the ambulance in which he was tending to the wounded took a direct hit.) They could have fled, but they remained behind to save others.

Bar set out with his car, rescued people, and then returned of his own accord to the valley of death to save others. On the way, in his capacity as a combat paramedic, he helped bandage the wounded. On the fourth round, he was attacked and taken captive.

Rom circulated and hid people. He was given a chance to flee, but he insisted on staying to help others.

Eitan was already on his way out of the area with the group he had rescued. On the way, he saw two murder victims, and insisted on staying to make sure they received a proper burial. In the middle of his chesed shel emes, he was abducted.

How can any of us remain apathetic in the face of this gevurah? There is good reason the country has been inundated with a wave of assistance and volunteerism. People have opened their homes and their pockets, as the chesed organizations and mutual assistance have been working overtime.

While the Nazis were focused on sowing discord, suspicion, and bitterness between Jews amid all the horror and uncertainty, perhaps this most recent tragedy — while there is so much we cannot fathom about it in the spiritual spheres — can also serve as some kind of catalyst for the opposite, for mutual responsibility and ahavas chinam to the level of mesirus nefesh.

And may we all emerge from the narrow straits to the great light, from exile to complete redemption very soon.

Rabbi Yisrael Goldwasser, a Gerrer chassid, is a well-known lecturer, historian, and veteran tour guide who accompanies groups to the death camps in Poland.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1010)

Oops! We could not locate your form.