Torah Haven in the New World

How Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg sowed the seeds of advanced Torah study in America

With additional research by Moshe Dembitzer

Photo Credits: YIVO, JDC Archives, Yeshiva University Archives, Machon Avodas Levi, Levenberg Family, Neuberger Family, Feivel Schneider, Pini Dunner, University of Texas-Austin Archives, Gordon Family, Walkin Family, The Jewish Historical Society of Greater New Haven

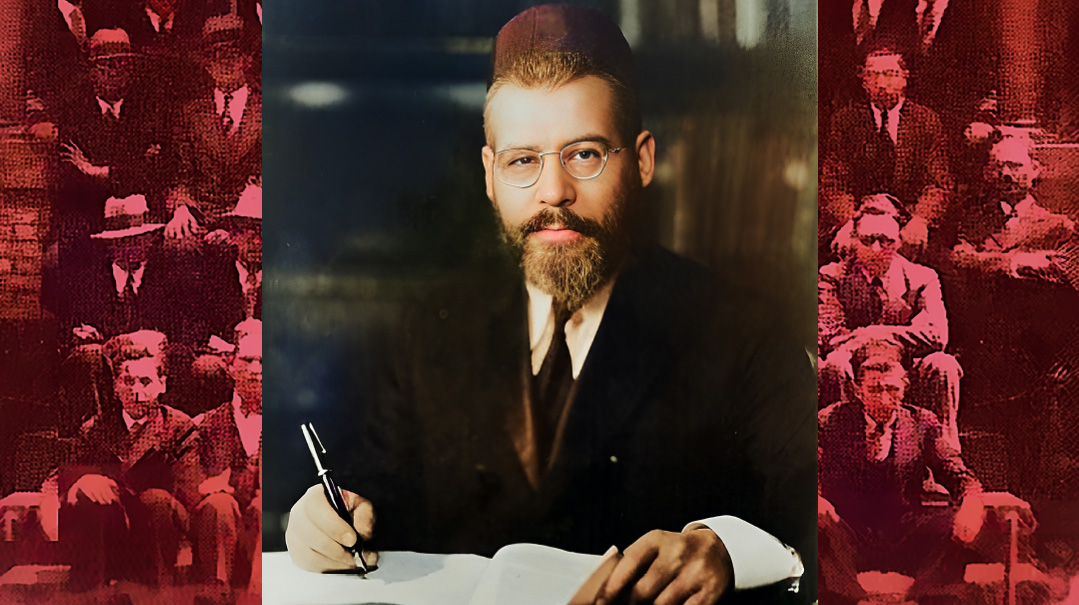

When Slabodka student Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg arrived in prewar America, his vision for a European-style mussar yeshivah was deemed foreign and unrealistic. Yet he marshaled the support and enthusiasm to open a unique institution on American shores, where students pursued the heights of Torah knowledge along with lofty character development.

He managed to lead his New Haven yeshivah for just a short, tumultuous period — but it left an outsized footprint on the postwar Torah world to come. Like the biblical Yehudah, Rav Yudel Levenberg traveled to a new, strange land ahead of his brothers, to build a yeshivah for the future arrivals. His yeshivah is no longer, but he will forever be counted as a founding father of America’s Torah world.

The summer of 1937 was a turning point for two young Montreal-bred yeshivah bochurim, Nosson Wachtfogel (1910-1998) and Shmuel Schechter (1915-2000). After several years of learning at the Mir Yeshivah in Poland, they had returned home at the behest of their parents, following the passing of the illustrious Rav Yerucham Levovitz (1875-1936). They had agreed that this respite would be a short one — soon they would return to Europe, to the great citadel of mussar in Kelm.

But soon after they arrived back in North America, an opportunity arose for the budding Torah leaders: to attend to the ailing Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg, a prime Slabodka talmid and the pride of the Alter himself. Rav Levenberg’s once-robust frame, now ravaged by a relentless onslaught of illness, bore the scars of a life dedicated to the tireless pursuit of Torah and mussar. A stroke had left him partially paralyzed, but his indomitable spirit remained unbroken.

Rav Nosson and Rav Shmuel did not hesitate. They recognized the magnitude of the zechus before them — to attend to a true gadol b’Yisrael, the leading baal mussar in America, who had devoted every fiber of his being to plant the seeds of Torah in the challenging soil of the goldeneh medineh.

And so, when July arrived, they found themselves at Kleinberg’s Hotel in Woodridge, New York, where Rav Levenberg’s talmidim had arranged for him to spend the summer months. The days were long and the work was arduous, but the two young men relished every moment spent in the presence of greatness. They witnessed firsthand the depths of Rav Levenberg’s mesirus nefesh and the sheer force of will that had propelled him to build Torah in America against all odds.

A trio in Kelm: (L-R) Rav Shmuel Schechter (future Beth Medrash Govoha mashgiach), Rav Nosson Wachtfogel, and their close friend Reb Aryeh Stamm Hy”d

As Elul approached, a spark of an idea took hold. They reached out to their friend Rabbi Alexander (Sender) Linchner (1908-1997), an early talmid of Rav Levenberg in New Haven, whose father-in-law, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz (1886-1948), had just opened Camp Mesivta in nearby Ferndale. Reb Shraga Feivel, who shared a deep bond of respect and common purpose with Rav Levenberg, immediately agreed to host the gadol for a shmuess on the eve of Rosh Chodesh Elul.

The arrival of Rav Levenberg at Camp Mesivta was a scene etched in emotion. The campers, resplendent in their Shabbos finery, sang and danced with unbridled joy. Their rosh yeshivah, the venerated Rav Shlomo Heiman — himself no stranger to the trials of ill health — stood at the camp’s entrance awaiting the arrival of his fellow general in the battle to build Torah in America.

As Rav Levenberg was wheeled into the dining room, a hush fell over the assembled crowd. The silence was so profound that the chirping of birds outside seemed to echo like thunder. And then, the gadol began to speak. Every word was an effort, every breath a labor of love. His voice, once a clarion call that had stirred the hearts of thousands, now faltered and slurred. But the fire in his eyes never dimmed. It was a testament to the indomitable spirit of a man who had given everything — his health, his strength, his very life — to ensure that the flame of Torah would burn bright on American shores.

Just a few months later, Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg was niftar, his earthly mission complete. As Rav Shmuel Schechter painted the scene five decades later, he put it quite simply. “He died al kiddush Hashem — for the sake of Heaven.”

But long before the final chapter of his life, he lived al kiddush Hashem — devoting every ounce of his strength and considerable talent to the yeshivos he built, the talmidim he inspired, and the countless lives he touched with his boundless devotion to Hashem and His people.

What sort of chief rabbi circles his city, begging for leftover tomatoes for the yeshivah bochurim in his care? What sort of elite yeshivah student forgoes a promised dowry so as not to pain a hopeful bride? What sort of rav faces arrest and imprisonment because of his refusal to compromise on kashrus?

Rav Levenberg was that sort of leader. He fused the highest standards of Torah learning with the highest standards of mussar, and built a European-style yeshivah in America a century ago, showing young American boys that they, too, could reach the heights of Torah greatness.

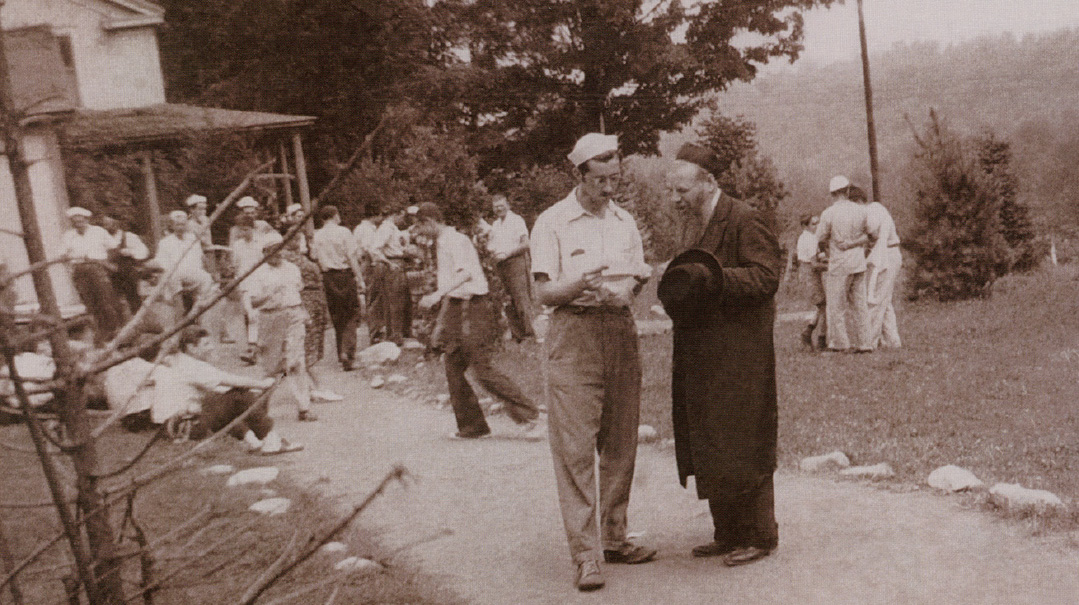

Rav Shlomo Heiman and Moshe Rapps in conversation at Camp Mesivta

To survey the landscape of Torah study in mid-20th century America was to behold the beginnings of an unexpected renaissance.

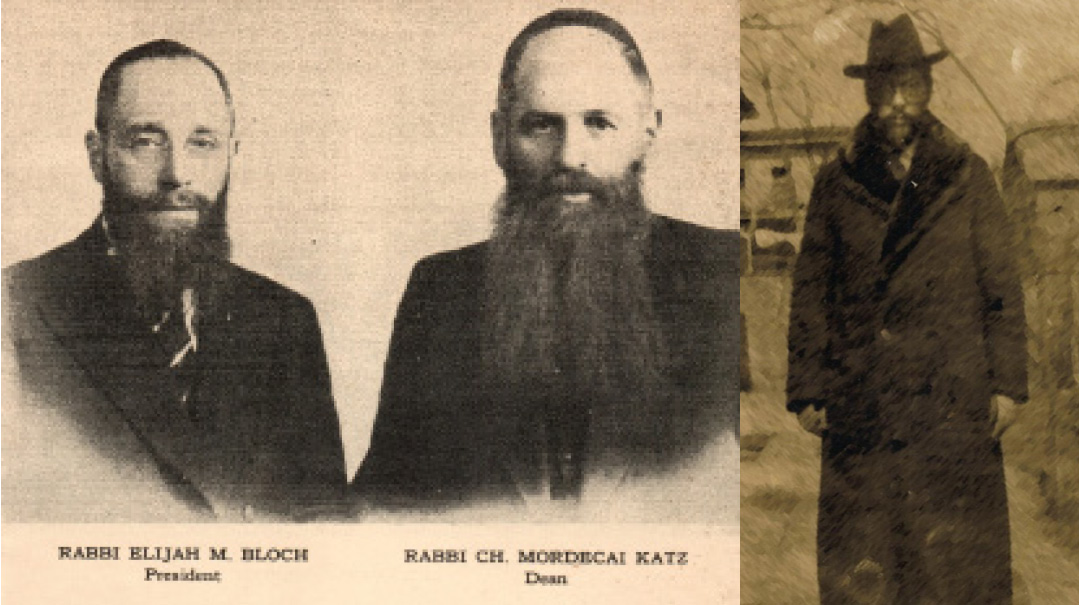

From the Midwest, where the glory of Telz was being restored, to the Mid-Atlantic region, from which proudly shone forth Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman’s Ner Yisrael, Jewish young men seeking quality Torah education now had some excellent options.

In New York City, America’s largest and most vibrant Jewish community was served by several advanced yeshivos, among them Mesivta Torah Vodaath (which also played a critical role in the origins of other yeshivos, such as Chaim Berlin and Lakewood). And on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Rav Moshe Feinstein had gained renown as an institution unto himself, a wellspring of Torah wisdom and halachic guidance for petitioners from coast to coast.

Girls’ education, too, wasn’t left behind, as the likes of Rav Boruch and Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan toiled to transplant the Bais Yaakov movement from its Krakow origins to the streets of Williamsburg and other Brooklyn neighborhoods.

These were relatively recent developments. Prewar America was a place of mass spiritual apathy and an era of rapid Americanization and assimilation. Torah Judaism was largely on the retreat, and every spiritual advance required tremendous grit and passion.

While every spiritual victory was hard fought, each had a unique narrative of struggle against adversity and indifference — no two battles (or those who waged them) were identical. And yet, for all the differences, each of the aforementioned legacy Torah institutions has a common thread woven into the fabric of their origin stories: Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg, and his Yeshivah of New Haven.

Chapter 1

THE GREATNESS WITHIN

A Mother’s Pride

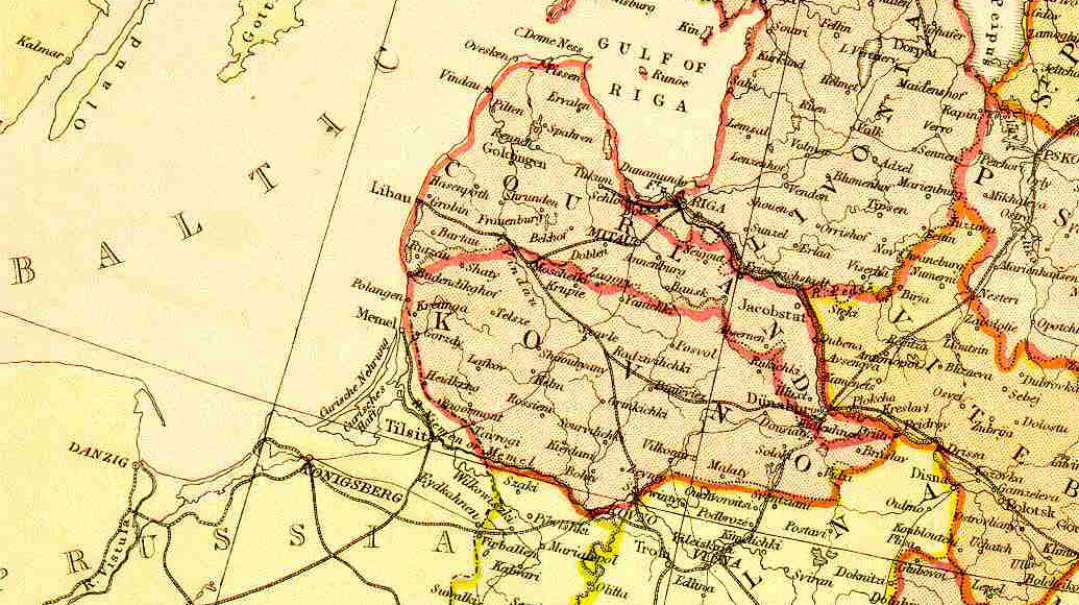

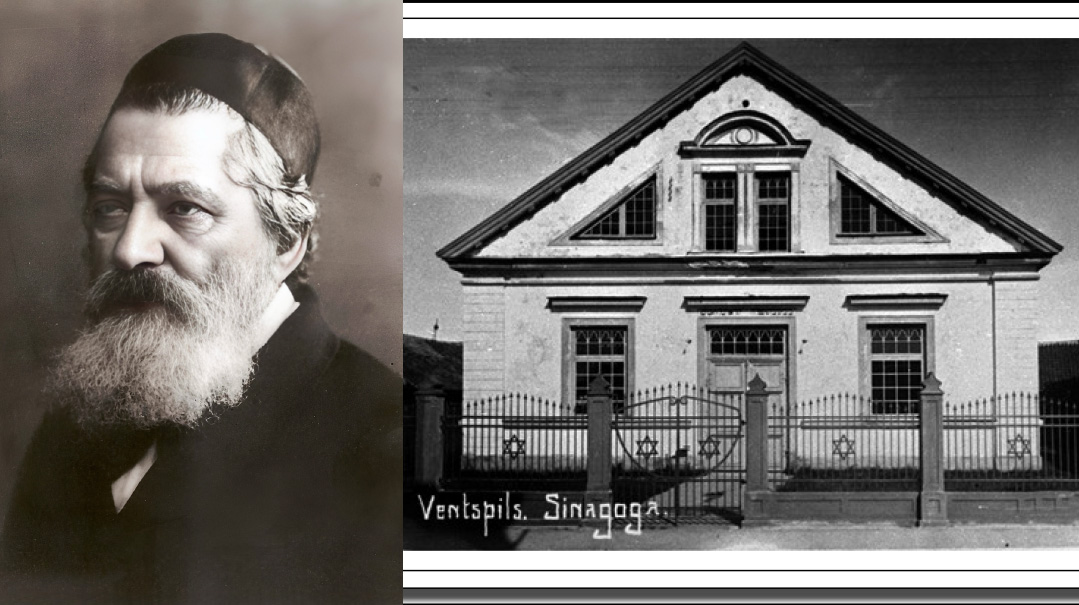

ON a cold December day in 1884, Tzvi Hirsch and Chaya Gella Levenberg had more than just Chanukah to bring joy into their home. The poor yet respected Levenberg family of Pilten, in the Courland region of the Russian Empire, had welcomed a new child into the world. They named him Yehuda Heschel.

Born in the Russian Empire during a time of great upheaval and change, young “Yudel,” as he was affectionately called, was an energetic and occasionally mischievous child who quickly learned to pour his boundless passion into his Torah studies. Not long after he learned how to read, he devoted himself to learning Chumash. Neviim and Kesuvim also captured his imagination. Many a time he was spotted climbing into bed, Tanach in hand, immersed in the sacred words until sleep overtook him.

As one childhood melamed remarked to Yudel’s brother, Rav Boruch Zelig (1879-1941), “Whatever complaints I have about Yudel melt away when I watch him sit down to learn with such energy and passion.” This dedication was matched only by Yudel’s sensitive heart and strong moral compass. On one occasion, when a melamed handed Yudel his stick and instructed him to hit a lazy fellow student, he absolutely refused, in an early demonstration of his compassionate spirit.

As a child, he voraciously consumed stories of tzaddikim, especially those with mussar themes. His friends would often gather round, begging him to recount the inspiring tales — foreshadowing his future renown as a spellbinding orator.

But the true fountainhead of Yudel’s inspiration was undoubtedly his righteous mother. The Levenberg children shared vivid memories of their mother reciting Tehillim, pouring her heart out while singing her praise to the One Above for the opportunity to raise her children in the ways of Torah.

Working tirelessly to obtain the means to provide her children with a Torah education, she would collect leftover groceries to put food on the table. Clothing her children was another struggle. Concerned for modesty, she gave Yudel an old, long coat to conceal his torn trousers.

Yudel felt unfortunate and dejected that his parents were so poor. He was often mocked by his peers and called various demeaning names. If he saw one of his classmates outside of school, he would run away, heart aching.

But as he grew older, he overcame his shame and made peace with his family’s financial status. Most importantly, he learned how to channel this experience into a lifetime of helping others and sympathizing with those most in need.

Later in life, Rav Levenberg would share with his students an unforgettable episode seared into his memory from his formative years. He described a bone-chilling winter night he spent awake learning in the town’s beis medrash. Illuminated only by the flicker of a lone candle, he sat hunched over a pile of seforim, voice rising and falling with the ancient cadences of the Gemara.

Suddenly, young Yudel was startled by the creak of the ezras nashim door. For a moment, a wave of terror washed over him — was it the deranged woman known to haunt the town’s dark streets?

Like his younger brother, Rav Boruch Zelig Levenberg — Rav of Talsen and martyred by the Nazis alongside his townspeople — was a proud Slabodka graduate

A soft cough broke the silence, followed by a voice he knew better than his own: “Yudel, it’s your mother! Don’t stop learning for even a moment!”

In the frigid night, his mother had stolen into the empty shul to catch the sweet strains of her son’s learning. Yudel’s melodic chant reverberating through the beis medrash was at once his mother’s deepest comfort and the prompt for flowing tears.

“That moment,” he would later say, “illuminated the darkest days of my life. The memory of those times — when I was destitute in everything but Torah — revived and sustained me.”

Spurred by his parents’ mesirus nefesh, Yudel embarked on his yeshivah journey at a young age. He learned in local yeshivos in the greater Latvian area, among them Zager (the hometown of Rav Yisroel Salanter), Novoaleksandrovsk (where Rav Raphael Shapira [1837-1921] had once served as rav), and Leckava, where his growth enabled him to advance to one of the formative yeshivos of the time.

(Left) Over 60 years after they studied in Maltch, Rav Yechezkel Sarna would endorse Rav Yudel for his superior oratory skills that “would bring the Jewish people closer to their Father in Heaven”; (Right) The Alter of Slabodka helped mold great roshei yeshivah such as Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Avraham Kalmanowitz, Rav Reuven Grozovsky, and Rav Yechiel Mordechai Gordon, and honed dominant mussar figures, including Rav Yerucham Levovitz, Rav Avraham Grodzinsky, Rav Meir Chodosh, and Rav Leib Chasman, to shape the next generation

Mentor for Life in Slabodka

Just a few months after Yudel was born, Rav Zalman Sender Kahana-Shapiro (1850-1923) was appointed the rav in the city of Maltch (Malech or Malec, in present-day Belarus). As a descendant of Rav Chaim Volozhiner (1749-1829) and one of the exceptional students of his cousin the Beis HaLevi (1820-1892) in the Volozhin Yeshivah and later in Slutzk, where the Beis HaLevi was rav, his credentials were impressive.

In 1898 Rav Zalman Sender was offered a position as rosh yeshivah in Knesses Beis Yitzchak in Slabodka (which ultimately was taken by Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz). In an effort to convince him to stay in Maltch, community leaders offered to open a yeshivah for him there. Yeshivas Anaf (branch of) Etz Chaim, named for his alma mater of Volozhin, was the result of this arrangement.

Maltch would become an important feeder institution for the great yeshivos of Lithuania, Knesses Yisrael in Slabodka in particular. Rav Aharon Kotler (1892-1962), Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky (1891-1986), Rav Yechezkel Sarna (1890-1969), Rav Avraham Jofen (1887-1970), Rav Isser Yehuda Unterman (1886-1976), and Rav Zalman Sender’s son Rav Avraham Dov-Ber Kahana-Shapiro (1873-1943) (the Dvar Avraham) were among those educated in the yeshivah, which was transported to the larger town of Krinik when Rav Zalman Sender assumed the rabbinate there in 1903.

Yudel Tolshiner (his family had since moved to the Courland town of Talsen or Talsi, as it’s currently known) was quick to adapt to the higher level of learning in Maltch. But it was the next leg of Yudel’s journey that would truly set him on a path to greatness. At the urging of his brother Rav Boruch Zelig, Yudel transferred to the Slabodka Yeshivah. There he became a devoted talmid of Rav Nosson Zvi Finkel (1849-1927), the Alter of Slabodka, a towering figure who revolutionized the yeshivah world with his innovative and uncompromising approach to mussar.

Gadlus Ha’adam — the greatness inherent in man — was the theme of the first shmuess a young Rav Nosson Tzvi had heard from his own teacher the Alter of Kelm, and it became the conceptual cornerstone upon which the edifice of Slabodka was built. Every teaching of the Alter seemed to be a further exploration of the tzelem Elokim of each individual, and his firm belief that man contained a reservoir of potential waiting to be actualized. He taught that mussar has the capacity to unveil and neutralize those forces preventing man from realizing his full potential. This concept, which emphasized the inherent greatness and potential within every individual, became the foundation of the Slabodka Yeshivah.

The Alter’s philosophy had a profound impact on his students, and Yudel was no exception. He internalized the Alter’s teachings, understanding that true greatness meant setting high expectations for oneself and constantly striving to reach one’s full potential. As he grew in his own learning and character development, he emerged as a natural leader.

“Der groiser baal regesh fregt — the greatly sensitive one asks,” the Alter of Slabodka would often mention while delivering a shmuess, and then he would elaborate on that point. Who did the Alter consider the “greatly sensitive one”? Yudel Tolshiner.

The bond between rebbi and talmid was a deeply personal one. Early on, the Alter recognized Yudel’s depth of feeling, goodness of heart, and genuine love for Hashem and His children. He saw in him a kindred spirit, a soul alight with the fire of Torah and the desire to serve the wider community. He took the young man under his wing, engaging him in lengthy discussions of mussar and life’s goals.

Rav Eliezer Poupko

Divine Symphony

Years later, following the Alter’s passing in the winter of 1927, Rav Levenberg addressed a large memorial gathering at the Pike St. Synagogue on the Lower East Side, speaking alongside the Alter’s longtime partner, the Slabodka rosh yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein (who was in the United States on a visit to raise funds and recruit students for the Slabodka yeshivah in Chevron). During the course of his two-hour hesped, Rav Levenberg shared a powerful firsthand experience:

When I studied in Slabodka, they used to raffle off barrels of petroleum, which the winner would then donate back to the yeshivah to keep its kerosene lamps lit. Pairs of students from the yeshivah would go around the Jewish homes in Kovno to sell them raffle tickets for the oil.

Once, the Alter sent me along with my friend Eliezer Poupko (1886-1961) from Radin (later a rav in the city of Haverhill, Massachusetts) to sell raffle tickets. Being young and naturally shy, I tried to avoid this mission, but the Alter insisted firmly, and I went. However, I devised a strategy. Every time we approached a house, I would open the door and push my friend inside, and I would stay outside.

When we returned to the yeshivah, my friend complained to the Alter about my strange behavior. The Alter called me in and said: “What do you think, that I have no one else to send in your place? There are plenty of students who could go. But I see in you a great shyness, and because it’s possible that one day you’ll need to knock on the doors of the generous, I want you to get used to it.”

When I came to America and entered the world of public service, I realized how right the Alter of Slabodka, of blessed memory, was. Not only was the Torah of Hashem constantly on his lips, but he also cared, like a compassionate father, for the future of his students. With his sharp eye, he penetrated the depths of their souls and natures, and tried to educate them and elevate them to the level of perfection.

His davening was indescribable. A fellow Slabodka student, Yisrael Chaim Becker, was told by the Alter, “If you want to hear someone daven properly, I advise you to daven along with Yudel from one siddur.” The student described the davening as pouring from the soul of Yudel. “He hypnotized me. I heard his davening as a G-dly symphony, singing and praising the Creator.”

(Rav Shmuel Schechter later described how Rav Levenberg’s great characteristic was that he was an oved Hashem. “We saw that when we were in Kleinberg’s Hotel when he was sick, he was very sick already, very sick, but the way he used to daven and the way he said Aleinu. The way he said aleinu l’shabei’ach in his matzav of yissurim — it was a culmination of a whole lifetime of avodas Hashem.)

Yudel’s time in Slabodka coincided with the great split in 1897 between the pro- and anti-mussar factions in the yeshivah. Reb Yudel entered the fray and thus gained firsthand experience understanding the dynamics of the opposing forces.

The writer, educator, and doctor Hirsch Leib Gordon (1896-1969), who studied in Slabodka before coming to the US, was a regular visitor to Rav Yudel’s home as a student at Yale. He wrote of Rav Levenberg’s valiant efforts to defend the Alter’s ideals, even sometimes having to use physical force to keep away his mentor’s detractors.

In 1904, young Yudel was ordained by a trio of leading Lithuanian rabbinic giants: Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein (1866-1934), his rosh yeshivah in Slabodka; Rav Aharon Walkin (1865-1942), the rav of Pinsk; and Rav Zev Wolf Avrech (1845–1922), the rav of Mazeikiai and the author of the responsa Revid HaZahav. Yudel Tolshiner was now Rav Yehuda Heschel Halevi Levenberg.

Revolutionary Fervor

As Rav Yudel prepared to leave Slabodka, a storm was brewing across the Russian Empire. Russia’s humiliating defeat in the Russo-Japanese War ignited a wave of unrest. The fast-moving current of the 1905 Revolution sucked in many youngsters, Jews included, seeking to exchange a life of hard work, poverty, and government oppression for the seemingly exhilarating role of a revolutionary.

The young Jews among these revolutionaries targeted their fellow Jewish youth, sometimes entering yeshivos while shouting slogans for the socialist Bund or other revolutionary parties and spreading propaganda. In his book With Fury Poured Out, Rabbi Bernard Maza (1926-2007) tells the troubling tale of a group of Jewish revolutionaries in Rokiskis, a town that stands on the current-day border of Lithuania and Latvia:

In 1905 a Jewish revolutionary group was formed in Rokiskis, spreading proclamations and organizing demonstrations against the Czar. The Jewish revolutionaries learned to handle revolvers on the Sabbath in the Rokiskis woods.

The story is told that a man named Velvele and his two sons spied upon the revolutionaries, and because of them, some of the revolutionaries were sent to Siberia. The revolutionary group decreed the death sentence against Velvele and his sons.

One Simchas Torah holiday in the morning, when the spies were in the beis medrash, they were shot at. But because the attackers did not want to hurt innocent people in the beis medrash, they only slightly wounded the spies. The boys who made the attack fled from the scene. Some were caught and sent to Siberia.

Amid this turmoil, Rav Yudel returned to his hometown of Talsen in the Courland district, a region with its own complex history. Situated north of Lithuania as the westernmost province of the Russian Empire, Courland was heavily influenced by its proximity to Germany. It was a region steeped in German culture and language, despite it being under Czarist rule since 1795.

Courland’s exclusion from the Pale of Settlement, the designated area where Jews were allowed to reside within the empire, further reinforced their distinctive identity. While this exclusion was not strictly enforced, it nonetheless contributed to a feeling of separateness, and a reluctance to fully integrate into the broader Russian Jewish community.

Being outside the Pale in both the literal and figurative sense left Courland’s Jewish population relatively demographically sparse, and they considered themselves more “western” and cultured than those within the Pale. In fact, many Jews in Courland spoke German rather than Yiddish.

This sense of distinctiveness, however, did not shield Courland’s Jews from the hardships that plagued the empire. Poor living conditions, economic instability, and religious restrictions fueled discontent among the Jewish population. As revolutionary ideologies like Marxism and socialism gained traction among the youth, the stage was set for a perfect storm of unrest.

The Cossacks’ Wrath

On that fateful day, December 5, 1905, the tranquil town of Talsen found itself engulfed in the flames of revolution. A legion of Cossacks, their hearts hardened and weapons poised, descended upon the town to quell the uprising with an iron fist. The air crackled with the sound of gunshots as the Cossacks fired indiscriminately, killing more than 20, among them several Jews, both revolutionaries and innocent people trying to flee. They pillaged with impunity, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake.

Rav Yudel ran for his life, fleeing his regular place in the attic of the local shul. In that moment of terror, he stumbled upon a wounded Russian man who was bleeding heavily. Rav Yudel mustered every ounce of his strength and carried the injured man up to an attic. He tore his own shirt to create makeshift bandages, tending to the man’s wounds with gentle hands and a compassionate heart. In a time when aiding revolutionaries was punishable by death, Rav Yudel risked everything to save a human life.

Once the revolutionary’s wounds were stabilized, Rav Yudel ran onward. He sought refuge in a house outside town, but the homeowner was already housing many men, women, and children. In a time of such turmoil, the presence of a young man of military age could put everyone at risk. Rav Yudel understood that he was not welcome — yet he felt no bitterness or resentment. Instead, he praised the homeowner for sheltering so many hapless souls. Then, he pressed on and found a hovel where he could hide.

As the third day of hostilities drew to a close, the Russian forces finally permitted the burial of the bodies that littered the streets. Fear still gripped the town, and few dared to venture out. Once again, Rav Yudel stepped forward, his courage fueled by his commitment to bring kevod acharon to those who were murdered. He braved the streets, recovering the bodies, cleaning the blood off the sidewalks and ensured a proper kevurah even for those completely disconnected from traditional Jewish life.

In the aftermath of the revolution, Rav Baruch Zelig found his brother in the attic of the shul, alone and weeping. His tears flowed not for himself, but for the plight of the Jews in Talsen and the surrounding towns — an expression of his deep love for his fellow Jews.

Rav Baruch Zelig later shared a poignant anecdote that illuminated his brother’s profound bitachon. When the dreaded conscription order from the Russian army arrived, Rav Yudel’s family was gripped by worry, knowing all too well the hardships and dangers that awaited Jewish soldiers in the Czar’s ranks. Desperate to spare him this fate, one of his elder siblings, who had found financial success in distant South Africa, sent a substantial sum of money, hoping it would be enough to sway the notoriously corrupt draft board.

Yet when Rav Yudel emerged triumphant, exemption in hand, he revealed that the funds had not been used as a bribe, but rather to acquire seforim. For Rav Yudel, this was not a gamble, but an act of pure faith, rooted in the timeless wisdom of Rav Nechunya ben HaKanah, who taught in Pirkei Avos: “One who accepts the yoke of Torah, absolves himself of the yoke of government [oppression].”

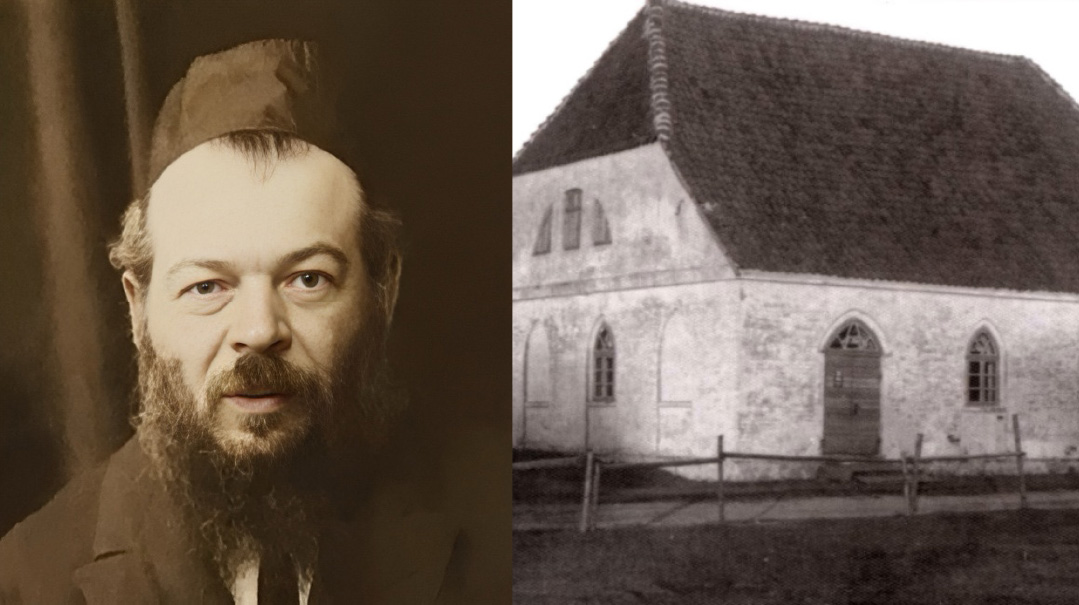

Rav Epharim Samunov and the shul in Windau

A Dowry Forgone

The following year, Rav Yudel became engaged to Devora Edelstein (1882-1944) of Windau (Ventspils), a port city on the Baltic Sea. Shortly thereafter, he discovered that much of what he’d been promised financially was false; his future mother-in-law had relied on funds she had hoped her sons in the US would send as a dowry.

Not wanting to break the engagement, Yudel traveled to Kelm, hoping the situation would sort itself out in the interim. After six months it became apparent that no change would be forthcoming. He telegraphed Mrs. Edelstein that he was forgoing any financial claim, and the wedding would proceed as planned. (Exhaustive research by the acclaimed genealogist Chaya Sarah Herman turned up records that show that a dowry was indeed recorded, so it’s possible that the funds came through at the last moment.)

The wedding took place a week after Shavuos of 1907. Their mesader kiddushin was the rav of Windau, Rav Ephraim Samunov (1860-1932), an esteemed musmach of Volozhin who was the son-in-law of Rav Chaim Berlin (1832-1912). (Rav Ephraim, who was well-schooled in the Russian language, helped defend the yeshivah before Russian authorities who demanded that secular studies be included in the yeshivah’s curriculum. Together with Rav Chaim Soloveitchik (1852-1918), he drafted the yeshivah’s position and the lobbying letters that the yeshivah management tried to implement.)

For the first years of his marriage, Rav Yudel lived in his wife’s hometown, organizing shiurim for local youth. Many of these youths attended the local gymnasium, and due to his influence began to abstain from writing on Shabbos, to the consternation of the gymnasium director and some of their parents.

When his mother-in-law’s business dealings became increasingly precarious, Rav Yudel took on loans to assist with the family’s finances. By 1910 his debts were mounting, and he realized something had to change. So in early February, he traveled back to Slabodka to seek guidance.

Rav Levenberg’s trip to Slabodka coincided with a period of sorrow. The rabbanim of both Kovno, Rav Tzvi Hirsch Rabinowitz (1848-1910), and the neighboring suburb of Slabodka, Rav Moshe Danishevsky (1830-1910), had passed away two weeks apart. Hespedim were organized in a large Kovno shul. The Slabodka talmidim urged Rav Yudel, who was known as a skilled orator, to deliver a eulogy.

He appeared on the bimah with a Midrash Eichah in his hands. It didn’t take long for the tears to start flowing. The crowds were so large that 15 minutes into the speech, people began fainting from the overcrowding, upon which the speech was abruptly halted. But even those who had not been familiar with the star Slabodka talmid from his time as a student there five years earlier, were now aware of his talent.

The Slabodka Yeshivah extended an invitation to Rav Yudel, proposing that he become their fundraising emissary in America. This offer seemed to echo the foresight of the Alter, who had apparently predicted such a role for Rav Yudel during his reluctant fundraising stint back when he’d been a student at the yeshivah. After careful consideration, the proposal set forth by Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein was accepted.

Consequently, Rav Levenberg prepared to embark on a new chapter in his life, making arrangements to immigrate to the United States and undertake his new responsibilities.

It should be noted that economic hardship was not the only motivation for Rav Levenberg to immigrate. Decades later, Rav Yitzchak Hutner (1906-1980) would reflect that Rav Levenberg’s journey to the United States in 1910 was the very first transatlantic migration undertaken solely l’Sheim Shamayim, for the purpose of spreading Torah and Yiddishkeit in the spiritual wasteland of early 20th-century America.

The National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives was what brought many Jews out to Denver in the early 20th century

Chapter 2

VISION FOR THE NEW WORLD

The Rabbi of Jersey City

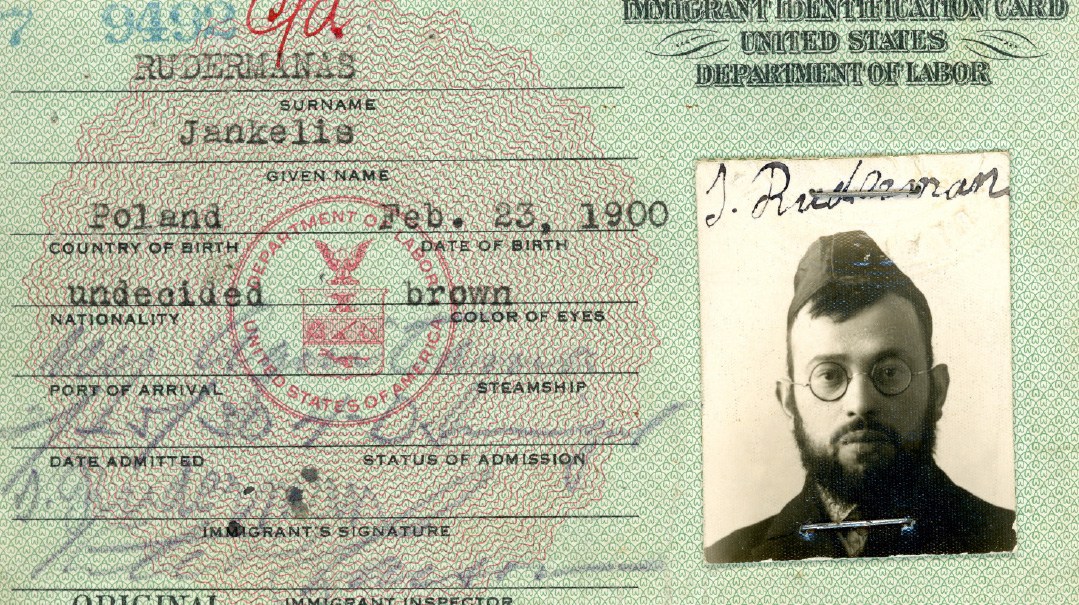

Rav Yehuda Heschel Levenberg sailed on the USS Pretoria from Hamburg on March 12, 1910, and arrived in New York City on March 25. While he would continue raising money for Slabodka for the next 28 years in his role as the president of the yeshivah’s robust alumni association, he quickly learned that America had no shortage of meshulachim and that his talents could be utilized in other ways.

By the summer of 1910, he had accepted an offer to serve as rav of several Eastern European congregations in Jersey City, New Jersey. The famed writer and activist Peter Wiernik (1865-1936) editorialized Jersey City’s good fortune in Der Morgen Zhurnal, congratulating the city’s Jews on gaining “this most learned and talented man,” as their new spiritual leader.

At the tender age of 25, armed with the eternal truths of Slabodka, Rav Levenberg stood poised to enter an American rabbinate that lacked young, energetic idealists. His devotion to every communal cause would redefine the local Jewish landscape, improving essential institutions such as the local Talmud Torah and the Jewish Children’s Home, as well as the city’s Jewish old-age home. As his renown grew, stories of quiet chesed surfaced.

Rabbi Mordechai (Max) Robinson of Denver (1886–1951) related one such episode to Rabbi Levenberg’s son-in-law and biographer Rabbi Yitzchok Tzvi Ever (1913-1971) in 1939:

One of the teachers at the Jersey City Talmud Torah that Rav Levenberg founded suddenly fell ill with an infectious lung disease, which at the time had no known cure. It was thought that the clean air and sunshine in Colorado could cure this disease, so he journeyed to Denver and was admitted to the National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives for treatment.

He soon took a turn for the worse, and doctors declared that they needed to operate or it was unlikely he would ever recover. The simple teacher, a recent immigrant, had borrowed money to get to Denver and lacked even a dollar to pay for the costly procedure. After much deliberation, he wrote a letter to Rav Levenberg in Jersey City, explaining the situation and that he absolutely needed several hundred dollars for an operation, otherwise, he would succumb to blood poisoning throughout his body.

Before long, he received a special delivery letter with a check signed by Rabbi Levenberg. Upon further examination, he realized that the amount was blank. Rav Levenberg enclosed a letter in which he clarified that the patient should write the amount needed on the check, but instructed him that it should not exceed five hundred dollars — “because I don’t have more in the bank than this amount.”

Rav Aharon Walkin, rav of Amtsislav, was tapped to take part in a mission to the United States along with Rabbi Dr. Meir Hildesheimer, the head of the Rabbinical Seminary of Berlin, on behalf of the Agudah

From Words to Action

In 1913, a delegation consisting of Rav Aharon Walkin and Rabbi Dr. Meir Hildesheimer (1864-1934) was sent to America to heighten awareness of the nascent Agudath Israel movement, which had been founded a year earlier in Katowice, Poland. As they searched for a spokesman to commence operation in America, they realized that the young, dynamic rabbi of Jersey City was the perfect candidate. His speeches attracted packed crowds, and he knew how to share a message with crowds both young and old.

The proposed launch of Agudath Israel in America did not get very far. The 1914 Knessiah Gedolah was postponed for nearly a decade due to the outbreak of the First World War. American Jewry united to help their suffering brethren overseas. Within a few months, Rav Yehuda Heschel was leading large rallies and fundraising events on behalf of the newly formed Central Relief Committee. A Jersey Journal reporter who was dispatched to cover one such event in February 1915 was transfixed by the young rabbi and shared an excerpt from his speech:

“Blood is flowing like water,” he said. “Aside from the question of war and its countless miseries, thousands, yes, tens of thousands of our poor coreligionists are actually starving: old men who never knew what want was, women whose husbands are at war, children and babies in arms, all are longing for that with which to keep their souls and bodies together, a little food upon which they can exist until conditions improve. They are crying aloud for a little help, and this help must come from us, the Jews of the United States.”

Our previous speakers have all lamented the overwhelming number of victims of this tragedy. Perhaps we should also consider its qualitative impact, which cannot be quantified or measured by any means.

What if George Washington had lost the war against England, and America had never come into being? Not only would America have suffered, but the entirety of humanity would have been altered, and Washington could have easily lost the war were it not for a Polish Jew named Haym Solomon, who contributed 600 thousand dollars. What if the Maccabees had not triumphed over the Greeks? The world would have been a markedly different place.

Who can predict the future of Judaism and humanity itself if we allow our brethren in Europe to perish? We must, therefore, be filled with a strong desire to repair and restore, not merely with words, but through genuine actions that show solidarity and empathy with the plight of our brethren in Europe. Then, as a result of our deeds, our Father in Heaven will extend His hand to us, end this senseless suffering, and guide us back to our true home.

Rav Moshe Zevulun Margolies (Ramaz) blesses a battalion of Jewish soldiers prior to their deployment overseas. In addition to raising funds for relief, rabbanim also worked to raise the spirits and religious conditions of troops being sent off to war

His impassioned pleas bore fruit. One month later, the same newspaper reported that 3,000 pounds of matzah were being sent to the besieged Jews of Palestine, who were trapped between the warring Ottoman and British militaries. The Jews of the Yishuv were starving and could not even afford basic religious necessities such as matzah for Pesach.

Rav Yudel’s speaking abilities were such that even local Reform Jews began to attend Jersey City’s B’nai Israel shul to hear his sermons. When he campaigned to build a new Talmud Torah in town, the local newspaper described how he had obtained funding from the wealthier Reform Jews, who most certainly had never before supported an old-world Orthodox institution.

But while his position as rav allowed him to have an impact on Jewish life and to support his family, Rav Levenberg felt unfulfilled. He wondered how he could fulfill his sacred calling, the Alter’s charge: to ignite the hearts of a generation with the light of Torah. That opportunity would soon arrive.

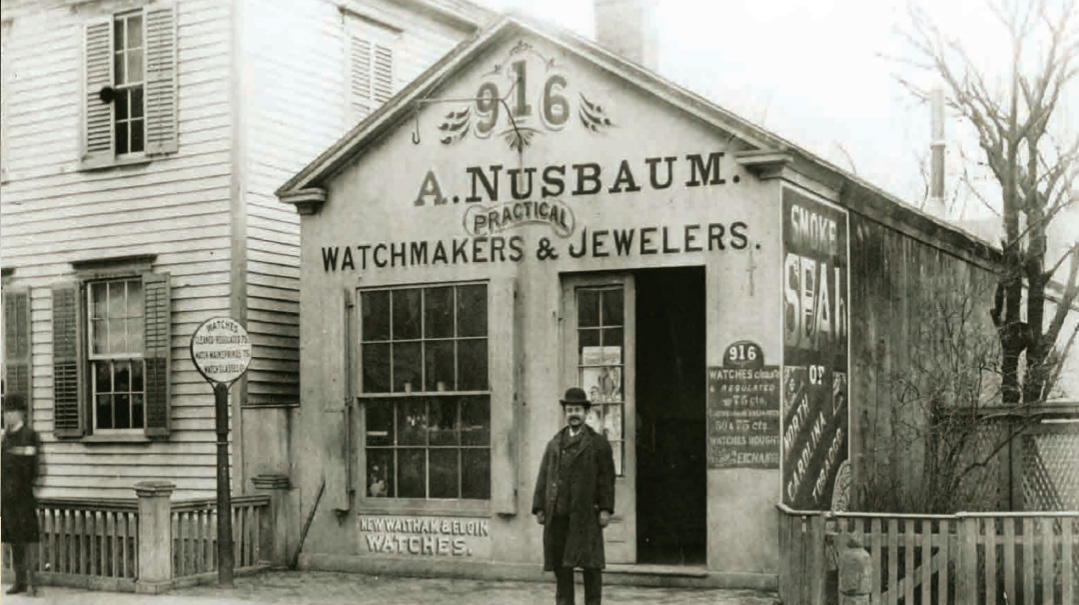

A Jewish proprietor outside his store in New Haven, early 1900s

New Horizons in New Haven

In 1916 Rav Levenberg was invited to visit New Haven, Connecticut to address a large community gathering in support of the war relief effort. He made a profound impression on his listeners and a group of community leaders invited him to move there and assume the helm of one of the local shuls — an offer that he accepted.

The community in Jersey City, devastated by the news of Rav Levenberg’s impending departure, promptly summoned the New Haven kehillah to a din Torah, but it was ultimately decided in favor of New Haven. At a farewell ceremony in Jersey City, which lasted until four a.m., Rav Levenberg was presented with a gold watch and an expensive walking stick. The Jews of Jersey City then voted to postpone the search for a replacement for a full year, hoping that, in the interim, perhaps Rav Levenberg might be persuaded to return.

As Rav Ha’ir, the chief rabbi of New Haven, Rav Levenberg commanded universal respect throughout the community, despite not receiving a direct income from his esteemed position. The eight volumes of the journal Jews in New Haven are loaded with testimonials to his selflessness and dedication while tending to the spiritual needs of his congregation.

Though his main pulpit was the majestic Rose Street Synagogue, B’nai Israel — the largest Orthodox shul in New Haven — his influence extended far beyond its walls. He gracefully circulated through all the local shuls, delivering powerful sermons that left an indelible mark on the hearts of his listeners.

Sarah Moore Lipwich vividly recounts a moving experience at the small Bradley Street Shul during the High Holiday season. “The shul was filled to capacity and was overflowing with standing room only, eagerly awaiting the presence of Rabbi Levenberg. As he graced the bimah and delivered his sermon, his words were so poignant that not a single eye remained dry in the congregation.”

Similarly, one Sam Dimenstein describes the profound impact of Rabbi Levenberg’s oratory skills at the old Congregation Sheveth Achim on Factory Street. “The dark-bearded rabbi’s dynamic and charismatic derashos were so effective that women seldom left the synagogue without shedding tears, deeply moved by his words.”

His son Rav Tzvi Hirsch (1922–2017), a longtime rebbi at Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin and the son-in-law of Rav Moshe Shatzkes (1881-1958), shared how Rav Levenberg’s influence extended beyond the Jewish community, as evidenced by the governor of Connecticut’s remark after hearing him speak: “If I could speak as well as you, I would already be president of the United States!” This despite the fact that the speech was delivered in Yiddish, a testament to Rav Levenberg’s ability to captivate audiences regardless of language barriers.

Even the gentile superintendent of the local Jewish nursing home found himself drawn to Rav Levenberg’s lengthy Yiddish speeches, standing in the corner and listening intently despite not comprehending the language. When asked about his regular attendance, the superintendent replied, “This man speaks from the heart, and that alone is worth listening to.”

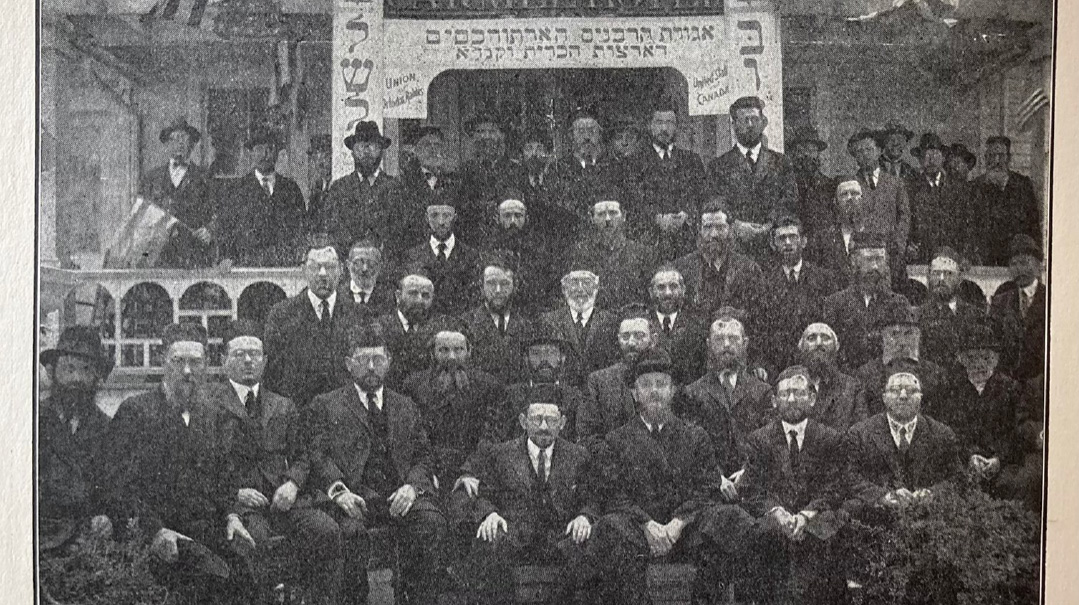

Outside Lakewood’s Carmel Hotel at the Agudath Harabonim’s 20th- anniversary convention in 1923

Only with Unity

But stirring speeches could go only so far. Rav Levenberg realized that in order to truly succeed as chief rabbi, he had to unify the city. He began to advocate for the organization of a Vaad Ha’Ir, a Jewish Community Council. He presented the idea to hundreds of community members:

Today’s assembly is not focused on merely one of our Jewish institutions. It is a much broader approach we are envisioning, that of a total effort that will lead to a united Jewish community endeavor with cohesive leadership concerned with all Jewish areas of endeavor.

Why is this so urgently needed? To offer but one example: the New Haven Community Chest gives its support to a variety of non-Jewish institutions. Our only beneficiary to date is the old-age home. We have no way of providing for the welfare of our needy. There is no shelter for the poor who arrive among us; there is no provision made for a kimcha d’Pischa fund. Above all, we are sorely in need of a proper Jewish educational system. Few, if any, of us have demonstrated dedicated work on behalf of that critical need.

I have decried this sad situation previously, and I shall continue to do so until the message strikes home to each and every one of you! Kashrus, Shabbos, mikveh, and the upbuilding of Eretz Yisrael, all of these demand our most dedicated attention and effort. We must become a united army to achieve these sundry goals. The Vaad Ha’Ir must be established for united planning and implementation.

Thus, the central Jewish coordinating body, the New Haven Vaad Ha’Ir, came into existence. Many a communal leader would consider that a crowning achievement. But for Rav Levenberg, it was just seen as a bridge to cross into new territory. He had been molded by a yeshivah, he knew the power of the yeshivah, and he wanted to bring that singular force to the Jews of his new country.

Rav Eliezer Silver was a steady supporter of the Yeshivah throughout its existence, so it was only natural that both Rav Levenberg and Rav Kramer attended his installation, in 1925, as Rabbi of Springfield, Massachusetts (an hour north of New Haven). Front row, left to right: unidentified; Dr. Samuel Friedman; Rabbis Bernard Revel; Yisroel Rosenberg; Moshe Zevulun Margolies (Ramaz); Eliezer Silver; Bernard Levinthal; Sheftel Kramer; Baruch Epstein (author of the Torah Temimah). Between Rabbis Rosenberg and Margolies is Rabbi Mayer Berlin. Between Rabbis Levinthal and Kramer is Rav Yehuda Levenberg. In the back, extreme right, is the Meitscheter Illui, with Rav Yehuda Leib Forer to his left

A Novel Proposal

In 1902, in the weeks following the tragic passing of Rav Yaakov Yosef, New York City’s Rav Hakollel, a group of European-born rabbanim from across the country gathered to appoint a successor. Though they were ultimately unsuccessful, they did establish a body devoted to furthering Yiddishkeit in America and strengthening its rabbinate.

The founders of the new organization, which they named Agudath Harabonim, didn’t trust the modern-looking, English-speaking and acculturated character of “Americanized Orthodoxy,” and drew its ranks exclusively from the pool of Eastern European immigrants in the rabbinate.

In April of 1923, the Agudath Harabonim announced that their 21st convention would convene the following month in the resort town of Lakewood, New Jersey.

The annual conference was an opportunity for those engaged in the lonely struggle of maintaining religious life among an increasingly disinterested public to meet one another, articulate the latest deteriorations in halachic observance, and propose strategies and solutions for those challenges.

Some of the assembled rabbanim at Lakewood’s Carmel Hotel, like the president of the Agudath Harabonim, Philadelphia’s Rav Dov Aryeh (Bernard) Levinthal (1864-1952), had been attending such events since the inaugural meeting. For others, such as Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin (1881-1973) — who had only just immigrated in February — this was their first encounter with the American rabbinic scene.

The convention of 1923 was consequential in several ways. A motion was passed to reform the internal leadership structure of the Agudath Harabonim, from a single president to a three-member presidium. This paved the way for the ascendancy of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s 41-year-old Rav Eliezer Silver (1882-1968) to a seat on the triumvirate, a position he would hold for the next 45 years.

Another hotly debated issue was the ongoing feud between the new Agudath Israel organization and the religious Zionist Mizrachi. Those gathered voted to send a delegation to both of the upcoming major Jewish conferences scheduled for the coming August: the 13th Zionist Congress (and the adjacent World Mizrachi Convention) in Carlsbad, Czechoslovakia, and the first Knessiah Gedolah of Agudas Yisrael in Vienna, in an attempt to broker a peaceful resolution.

On the evening of Thursday, May 10, the final night of the convention, Rav Eliezer Silver introduced a visiting guest from Poland, the 28-year-old Rav Menachem Mendel Kasher (1895-1983). Rav Silver presented the young visitor as the visionary behind a bold project to publish an edition of the Chumash, to be named Beis HaTalmud V’HaMedrash, which would juxtapose the rich treasury of Torah shebe’al peh with the pesukim of Torah shebichsav. Rav Kasher would indeed realize this vision, publishing 30 volumes of his (ultimately titled) Torah Sheleimah, beginning in 1927.

Following Rav Kasher’s speech, it was Rav Levenberg’s turn. Standing in a hotel on the corner of Princeton Avenue and Fifth Street, in the town that would be host to a world-class yeshivah two decades later, 39-year-old Rav Yehuda Levenberg began to describe his vision.

Land of Possibilities

The Yiddish journalist Ephraim Caplan (1878–1943), assigned to cover the convention by Der Morgen Zhurnal, filed the following report of his address, the final one of the conference (followed only by the brief installation ceremony of the new presidium):

It takes a while before he begins. His appearance is exceptionally pale, his eyes blaze fire through his glasses, and he sways as though in the middle of a deep sugya… eventually he starts:

“Rabbosai, Rabbanim, Gedolei Torah…

“For a long while now, I’ve been carrying with me a grand dream, which I have often considered beyond me. The dream comes to me, however, because when I was taking leave of Rav Nota Hirsh [Finkel], the Mashgiach of the Slabodka Yeshivah [13 years ago], he remarked: ‘You are setting out for America. It is a land of great possibilities. Go ahead and make it your task to establish a yeshivah of the Slabodka orientation.’

“I have no intention of competing with Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan [RIETS] — it must continue to occupy its respected position. But I do believe that there is room in America for additional centers of Torah learning.

“I already have a seed fund of fifteen-thousand dollars. The laymen of New Haven are excited about the idea, and have committed to providing a structure for the yeshivah.

“Moreover, I have negotiated with Yale University, and they have agreed to accept any young man who has completed studies at a European yeshivah and can bring proper documents attesting to that fact.

“Moreover, students at the proposed New Haven Yeshivah will, after three or four years, be admitted to Yale, without having to waste time on secular studies. The primary concern of the students will be Torah study, to develop one’s self in learning, and to swim in the sea of Talmud.

“I ask of you for your endorsement of my plan, that my longtime dream may become a living reality.”

To Rabbi Levenberg’s plea, Rabbi Levinthal, president of the Orthodox rabbinic body, responded with enthusiasm: “Go forward with strength. We not only approve of your proposal, we will assist you in any way we are able.”

In his 2022 article, “The New Haven Yeshiva, 1923–1937: An Experiment in American Jewish Education,” Dr. Ira Robinson writes that the New Haven Yeshivah was a novel concept for America.

“The two major yeshivahs previously created, the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in New York, and the Hebrew Theological College of Chicago, were in the major tradition of ‘Lithuanian’ yeshivot founded in Eastern Europe in the nineteenth century,” he explains. “However, neither followed the mussar tradition emphasized in Rabbi Levenberg’s Slabodka Yeshivah. Perhaps spurred by the founding of the Hebrew Theological College in 1922, the first such institution established in North America beyond New York City.”

But the yeshivah was novel for other reasons as well. New York and Chicago were the epicenters of the American Jewish community. The yeshivah in New Haven was to be America’s first “out-of-town” yeshivah, far from the dense and distracting masses of the immigrant neighborhoods of the Lower East Side and Chicago’s West Side.

Furthermore, it was the first yeshivah founded solely upon the idea of “Torah lishmah” — a post-high school institute of full-time Torah learning, which wasn’t an outgrowth of a local elementary or high school and didn’t have a stated goal of rabbinical ordination as its official curriculum. (The younger, high school-age students at New Haven did in fact attend secular studies offsite, in accordance with State law.)

It’s unclear whether Rav Levenberg’s pioneering concept was taken seriously by his colleagues at the Agudath Harabonim. They were focused on boosting the struggling Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan, which they hoped would gain prestige and badly needed funds due to the recent hiring of Rav Shlomo Polachek (1877-1928), the Meitscheter Illui.

But Rav Levenberg felt driven to at least make the attempt. America, his mentor had told him, was the land of possibilities. Surely, he had to try.

Rav Yehuda Levenberg and Rav Moshe Don Sheinkopf from the early days of the New Haven Yeshivah. The Alter insisted that the students in Slabodka appear neat and well-dressed at all times. He would say, “A hole in the sleeve is a hole in the head. A creased and tattered hat signifies a confused mind.” In the early days of the Slabodka Yeshivah, he even had a tailor on the premises to mend garments

Chapter 3

THE DREAM COMES TO LIFE

The Yeshivah Neighboring Yale

Upon his return from Lakewood, Rav Levenberg immediately began to develop the yeshivah project. He organized a lay committee consisting of local balabatim, and disseminated the following missive via the Yiddish press:

The New Haven Yeshivah will open officially in the month of Elul (August). Our yeshivah will work in close cooperation with rabbis throughout America. Our course of study, aside from Talmud, will include mussar works for the ethical and moral improvement of students. Full opportunity will be given to the students to proceed with their secular studies. Scholarship assistance will be extended according to individual need. Young men interested in enrolling in the New Haven Yeshivah are urged to submit their applications immediately.

The guest list at the Agudath Harabonim included a recent immigrant who was perhaps its youngest participant: a 23-year-old Slabodka student named Rabbi Moshe Don Sheinkopf (1900–1984). Having arrived in the US in December, the as-yet unmarried Rav Moshe Don assumed the pulpit of the Chochmas Adam Anshei Lomza Congregation on the Lower East Side (the Sheinkopfs came from the Lomza region).

Not long after the conference in Lakewood, Rabbi Levenberg announced that Rav Moshe Don was his choice as rosh yeshivah of the proposed institution. A short while later, Rav Sheinkopf married Rivka Seltzer, the daughter of one of the leading members of the Agudath Harabonim, Rav Yehuda Leib Seltzer (1869–1959) of nearby Bridgeport, Connecticut (Rav Seltzer had served as the rav of Patterson, New Jersey while Rav Levenberg was in Jersey City).

Now the yeshivah needed a building. On July 28, 1923, attorney Joseph Kaletsky obtained a charter for the New Haven Yeshivah, and a house at 83 Park Street, directly across the street from Rav Levenberg’s home, was purchased with the help of several local guarantors at the cost of $30,000. The ten-room mansion had formerly housed students from Yale University, and was now repurposed as a yeshivah — complete with a beis medrash, dining hall, and several dormitory rooms. Rav Levenberg’s dreams and hopes were becoming a reality.

The official opening of the New Haven Yeshivah took place on Sunday, August 12, 1923, with the participation of leading rabbanim from New York, New Jersey, and New England. The keynote speaker was the longtime rav of Hartford, Connecticut, Rav Tzemach Hoffenberg (1857–1938). Other attendees included distinguished rabbanim such as Rav Yosef Konvitz (1878-1944), Rav Yisroel Rosenberg (1875-1956), Rav Yitzchok Siegal (d. 1976), and many others.

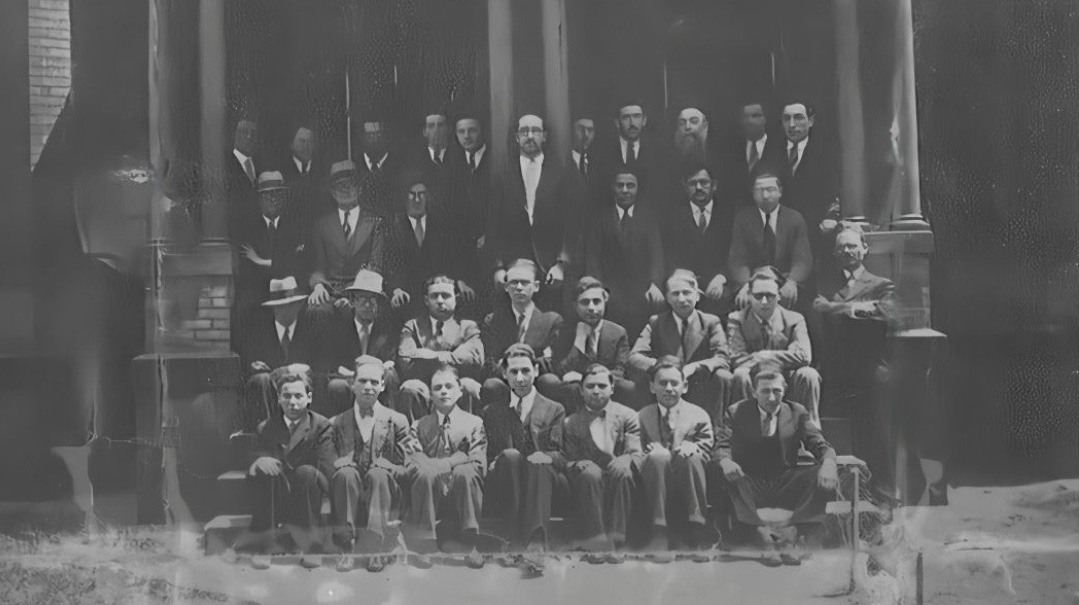

(Left) Students at the New Haven Yeshivah, including Shmuel Levenberg (bottom) and Moshe Eliyahu Gordon (center); (Right) The mansion at 83 Park Street, which once housed students from Yale, would now be the home of America’s first out-of-town yeshivah

The Outreach Effect

The event also attracted a large attendance of New Haven locals who were impressed by what they saw and heard, especially the voices of authentic Torah study reverberating from the newly gathered student body.

A report in the Bridgeport Telegram on October 25, 1923, claimed, “There are at present 20 students enrolled, many of whom are also studying at Yale University.” This seems to be in addition to local boys who attended the yeshivah for half a day while also enrolled in a local public school.

Three years later, the yeshivah took this a step further when it invited Jewish students at Yale to eat meals and, in some cases, even to reside in the yeshivah’s dormitory. This concept saw limited success, leading the yeshivah to initiate a campaign to purchase another home closer to the university. This residence, Rav Levenberg hoped, could serve as truly Jewish “fraternity” where students could reside in a traditional Jewish environment under the supervision of the yeshivah. Perhaps this was America’s first campus kiruv initiative.

In addition to kiruv efforts at Yale, Rav Levenberg brought the fledgling Young Israel movement to New Haven in 1927. A letter to Dos Yiddishe Tagblatt extolled those efforts:

Several weeks ago, Rabbi Judah Levenberg, chief rabbi of New Haven, assembled about a dozen boys and stressed to them the necessity and significance of an organization that would tend to unite the Jewish youth of New Haven, and implant and disseminate traditional Judaism in and among the Jewish boys of New Haven. Rabbi Levenberg organized the Young Israel right there and then.

Under the leadership of Mr. Nathan Rosen of the Yeshivah of New Haven, the membership has increased by leaps and bounds. Last Saturday, less than two months since the Young Israel was organized, we had an attendance of 80 boys. Isn’t that remarkable?

Rabbi Levenberg was present and in a very inspiring talk expressed his amazement at such a prompt realization of his dreams. The services are held in the beautiful and spacious auditorium of the B’nai Israel Synagogue. They are conducted along purely traditional lines and are beautified by harmonious congregational singing and perfect decorum. We have our own “chazzanim” and “gabbaim” and all the necessary “klei kodesh.”

Rav Levenberg in the library of the yeshivah, surrounded by talmidim. First on the right is Elya Moshe Gordon

Reb Yaakov Yosef Herman, Recruiter

The student body of the new yeshivah came from across the Northeast. One of the yeshivah’s best recruiters was Reb Yaakov Yosef Herman (1880-1967). In All for the Boss, his daughter Ruchoma Shain (1914-2013) describes how her father was able to send 14-year-old Shachne Zohn (1910-2012) to New Haven in 1924:

Rabbi Shachne Zohn, a former rosh yeshivah in Torah Vodaath in Brooklyn, New York, and presently rosh yeshivah of a kollel in Yerushalayim, is a product of Papa’s special care. At 13 years of age, he was attending public school on the East Side. After school, his father sent him to the Mordechai Rosenblatt Talmud Torah at 134 Henry Street where he received religious training for an hour and a half.

Mr. Zohn had a little cap business that kept him occupied all week. The few hours on Shabbos which he was able to spare for his son were too few to instill in Shachne the love for Torah learning. His father therefore was concerned about his son’s religious education. He knew Papa and had heard of his deep influence on young boys. He brought Shachne to Papa and placed him under Papa’s guidance. Papa immediately withdrew him from public school and registered him at Yeshiva Rabbi Jacob Joseph.

Shachne joined the group of 45 boys to whom Papa taught Ein Yaakov in English each evening at Tiferes Yerushalayim. A short while later after Shachne began studying at the yeshivah, Papa used his tactful pressure to convince Shachne to go to the New Haven Yeshivah where Nochum Dovid (Herman), Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, Boruch Kaplan, Reuven Epstein and a few of Papa’s other talmidim were already studying at Papa’s urging.

Ruchoma Shain continues that her Papa did not stop there: he maintained constant contact with Rabbi Levenberg and the other roshei yeshivah regarding the progress of “his boys.” When they returned home for the Yamim Tovim, he inquired into every detail of their lives and learning.

When Shachne had completed four years of study in the New Haven Yeshivah, Reb Yaakov Yosef advised him to continue his Torah studies in Mir, Poland. More than a half-century later, Rav Zohn became emotional in an interview about his New Haven years:

Rav Herman was my first rebbi and also Rav Boruch Kaplan’s first rebbi and Rav (Chaim Pinchas) Scheinberg’s first rebbi. Because he gave us the hashkafah of yiras Shamayim, because in those days, something like over seventy years ago, America didn’t have (European-style) yeshivos…. He was the one that inspired all of us that we should go to New Haven and then we should go to Europe…. He was de Tatte… like Avraham Avinu fahr yenne tzeit. They [his talmidim] were the nucleus of New Haven, and were his best, his best, the top, of New Haven talmidim.

Saved from New York’s Trolleys

Rav Boruch Kaplan (1909-1996), who along with his wife, Rebbetzin Vichna (1913-1986), would eventually revolutionize Bais Yaakov in America, was another one of the boys from the Lower East Side who was sent to New Haven by Rav Yaakov Yosef Herman.

In Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan — The Founder of the Bais Yaakov Movement in America, Rav Boruch’s son Rabbi Shimon Kaplan quoted his father: “Ehr hat mir arois geshlept fun unter der redder, he [Rabbi Herman] dragged me out from under the wheels [of the trolleys and cars],” a reference to the fate of most of his childhood friends, who were lost to the trials and tribulations of the streets of New York.

Boruch Kaplan arrived in New Haven in June, shortly before the yeshivah broke for the Av summer intersession. Undeterred, he worked day and night to catch up to the students who had arrived the previous September. It was hardly a coincidence that the student whom Rav Zohn described as the best bochur ever produced by New Haven would be brought up to speed by a Torah genius who had once been known as (along with Rav Aharon Kotler) the top student in Slabodka, Rav Yaakov Safsal, best known as the Vishker Illui.

A humble giant who eschewed the limelight, Rav Yaakov devoted endless hours to honing the skills of the boy from the Lower East Side who never seemed to run out of energy or thirst for additional Torah knowledge. When bein hazmanim arrived, the pair continued learning in the empty beis medrash.

Late at night, when the lights went out, Boruch Kaplan could be seen learning from the glow of the pilot light of the oven. The yeshivah’s cook, who happened to hail from the city of Pinsk, took pride in his landsman and even provided him with meals during the monthlong intersession.

By the time the rest of the students returned in Elul, Boruch Kaplan had morphed from a boy who could not learn a single blatt Gemara, to a master of all of Maseches Gittin with Tosafos.

To Create Menschen

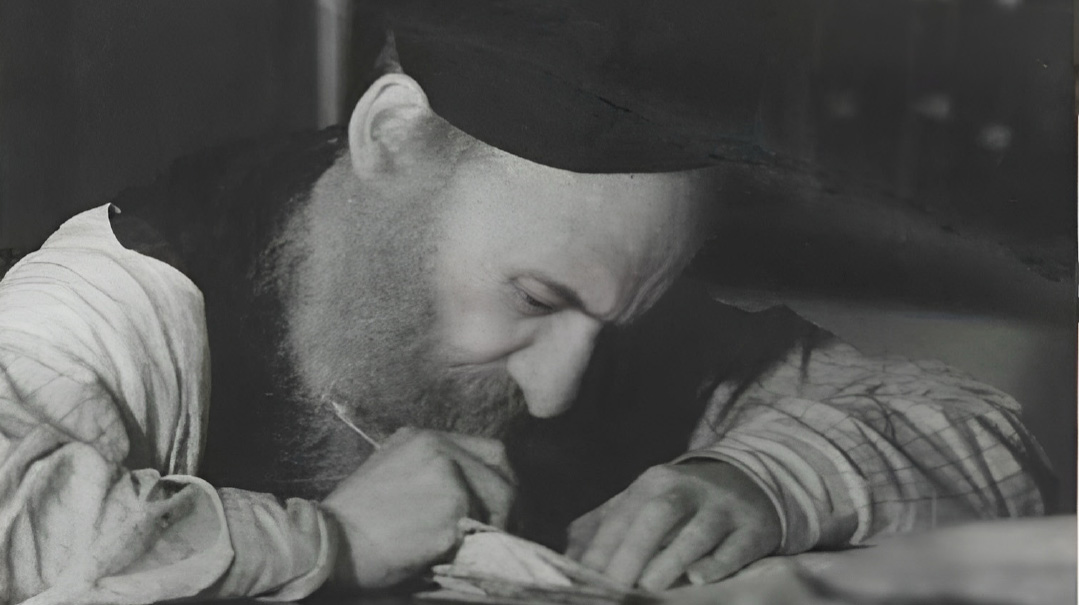

Even as his young charges thrived in their Torah study, Rav Levenberg reminded them that without mussar, their learning could all be for naught.

The story is told of a man who questioned Rav Yisrael Salanter, “Rebbi, I have only fifteen minutes a day to learn Torah. What should I study?”

Rav Yisrael replied immediately, “Learn mussar.”

“Why mussar?” asked the man.

“Because,” responded Rav Yisrael, “if you start learning mussar, you’ll realize that you have more than fifteen minutes a day to learn!”

Asked the difference between him and the Alter, the Chofetz Chaim reportedly said with his trademark humility, “I write books, he creates menschen [men].” The same could be said for Rav Levenberg, who sacrificed everything to mold menschen in a place where everyone said it was impossible.

One former student of the yeshivah, Rabbi Abraham Bick (1913–1990), wrote a glowing account of the atmosphere on Shabbos afternoons, when Rabbi Levenberg presented his popular mussar shmuessen:

The writer of these lines studied a considerable time in the New Haven Yeshivah, and the atmosphere of late Shabbat afternoons toward twilight is still fresh in my memory. Rabbi Levenberg, deep in thought, would enter the four walls of the cottage on Park Street where the students would be waiting silently at their study lecterns for his discourse. Rabbi Levenberg would break out in a niggun, and in the last play of light and shadow, he would commence his mussar discourse.

In his 2004 Jewish Observer piece entitled “Torah Shines Forth… From New Haven to Cleveland,” the author Rabbi Dr. Ari Z. Zivotofsky writes:

When I asked Rabbi Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, venerable rosh yeshivah of Torah Ore in Yerushalayim’s Mattersdorf, for his recollections about the yeshivah, he pointed out the obvious — it was a VERY long time ago, and it is difficult to remember details. But when I mentioned Rabbi Levenberg, a smile crept across his face as he related that Rabbi Levenberg was a masterful speaker. And then Rabbi Scheinberg began humming as he told his son and me how Rabbi Levenberg would sermonize in a singsong manner that captivated his audience. He seemed to stare inside his mind and dust off old internal pictures as he told us that to this day, he can visualize Rabbi Levenberg standing at the shtender, giving one of his masterfully delivered derashos.

Of Lithuanian Caliber

In early December 1923, Rav Eliezer Silver arrived from Harrisburg as a delegated examiner of the yeshivah’s progress for the Agudath Harabonim. On December 7, 1923, Dos Yiddishe Tagblatt of New York shared Rav Leizer’s report:

I wish to express my joy and pleasure at having visited with the heads of the New Haven Yeshivah. I saw far greater achievement than I had expected. I found learned young men who are completely devoted to the study of the Torah. When I shared with them my shiur (which lasted four hours!), I was astounded by their excellent response. They demonstrated sensibility, logic, and a deep grasp.

I listened to the shiurim of the faculty, and they were of a caliber to be heard in Lithuanian yeshivos. I was moved by a mussar discourse that I heard [from Rav Levenberg]. As of now, there are twenty advanced students enrolled and another twenty of lesser background. There is orderliness in this institution.

I have every reason to believe that the New Haven Yeshivah, under the guidance of its dedicated rabbis, will indeed flourish. May its reputation grow far beyond New Haven’s confines.

A New York journalist, Shimshon Erdberg (1891–1962), who covered Rav Leizer Silver’s visit, reported his personal observations in detail:

The students rise at seven and hold morning prayers. At eight thirty they have breakfast. From nine to twelve, they study and then break for an hour’s lunch. At one o’clock they conduct the Minchah prayers, and thereafter, until six, they continue with their studies. From six to seven, they conduct the “mussar session,” after which they proceed to Maariv prayers. Their English studies are then conducted (those who were still in high school) after a quick dinner, until ten o’clock.

In the lower department, which consists of students from New Haven, they study beginner’s Talmud, Tanach, and the Hebrew language. They are involved in these studies from four to seven thirty and attend evening high school sessions. There is a remarkable spirit among the student body. What a beautiful scene it was to behold!

Rabbi Silver had good reason to be impressed! I am delighted by New Haven’s achievement and hope that other American cities will emulate its efforts. Blessed be the New Haven laity who have helped to establish this yeshivah. Rabbis Levenberg and Sheinkopf are truly remarkable men; the students are treated by them in a most fatherly manner.

Though its initial enrollment was small, the yeshivah steadily gained popularity. Writing in late August of 1924 as the yeshivah began its second year, Rav Sheinkopf informed his acquaintance Tzvi Chaim (Harry) Epstein (1903-2003) (then studying under his uncle Rav Moshe Mordechai in Slabodka) that “students from all over the country are streaming to the yeshivah. However, we are regrettably unable to accept all who apply, owing to the [financial situation], which is extremely limited.”

Living Examples

The staff of the New Haven Yeshivah was graced by several eminent Torah scholars who served as a living example to the American-born students, demonstrating the heights a true talmid chacham could reach.

In the summer of 1926 Rav Sheinkopf was hired by the brand-new Mesivta division of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, a move heralded by a rare letter from the Alter of Slabodka himself to Dos Yiddishe Licht. This exemplified the spirit of Slabodka, which aimed to exert influence over Torah institutions and press its mussar ideals, even at the expense of its own institutions. A couple of years later, when he was appointed rav of nearby Waterbury, Connecticut, Rav Sheinkopf rejoined the New Haven Yeshivah, delivering a shiur several times a week.

Sometime in late 1924, Rav Levenberg approached his student Sender Linchner with an urgent fundraising mission: Rav Sheftel Kramer, a brother-in-law of Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, had agreed to join the faculty of the yeshivah, and funds were needed to pay for his passage. By then, Rav Sheftel was a familiar name in the yeshivah world, particularly in the Slabodka orbit.

Born in 1875 in Lygumai (present day Lithuania), he studied in Telz and Slabodka and was considered one of the illuyim of his era. During his time in Slabodka, Rav Sheftel developed a reputation as a strong defender of mussar (particularly during the tumultuous period of 1897 in Kovno and Slabodka), and the Alter selected him to join an elite group of students who traveled to Kelm, studying under that institution’s famous Alter.

In 1902, Rav Sheftel married Devorah Frank (1878–1966) of Alexot, thereby joining one of the most prestigious families in the mussar yeshivah world: Devorah’s sisters were already married to, respectively, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer (1870-1953), Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, and Rav Baruch Horowitz (1870-1936) (her late father, Rav Shraga Feivel (1843-1886), had been among the most dedicated financial supporters of the mussar yeshivos).

Several years later, in 1907, Rav Sheftel joined Rav Isser Zalman in Slutzk, serving as the menahel ruchani of the yeshivah. At a time when the Haskalah attempted (with some success) to make inroads into the yeshivos of Eastern Europe, the new Mashgiach developed a reputation as a zealous guardian against any such hostile winds.

Rav Sheftel served in Slutzk until the upheavals of World War I landed him and his young family in Kharkiv, where he used his experience and talents to set up a yeshivah there, serving the young men among his fellow refugees.

With the conclusion of the war (and the communist takeover of Russia, where Slutzk was situated), the Kramers found their way back to Slabodka, where Rav Sheftel tried his hand at a business endeavor to support his family. The Alter, however, insisted that he share from his wellsprings of Torah and yiras Shamayim with the local yeshivah students, and Rav Sheftel began delivering private shiurim and sichos in his home. He was also active in the local Tiferes Bochurim, a learning program for young men in the workforce.

(According to one report, during this interwar period, when the border between Lithuania and Poland was sealed — greatly reducing the Alter’s impact on the Eastern European yeshivos of Poland — a plan was hatched to sneak a group of students led by Rav Sheftel into Poland, to infiltrate the yeshivah in Volozhin. Ultimately however, this did not materialize.)

“Get Close to Reb Sheftel”

By the time Rav Levenberg’s invitation to join the New Haven Yeshivah arrived, Rav Sheftel was struggling to make ends meet. Adding to the financial strain was the marriage, in early 1924, of his eldest daughter Feiga to one of the bright stars of Slabodka: a young illui from Dolhinov named Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman (1900-1987).

Rav Sheftel Kramer traveled to the United States, alone, in November 1924 (his two teenaged unmarried daughters would join him in the summer of 1926, while his wife and two youngest daughters would not arrive until another year had passed), and officially joined the yeshivah several months later, in early 1925.

It took some time for the American-born students to adjust to Rav Sheftel’s shiurim and shmuessen. Reb Yitzchak Ber Gordon (1879–1957) of Richmond Hill, New York, wrote to his son Eliyahu Moshe who would go on to learn in the great Torah centers of Europe, encouraging him to properly utilize the living sefer Torah in New Haven’s midst:

Reb Sheftel is a precious beloved Jew, of great character. He is a doer of good deeds. All these in addition to being a great learned Torah scholar. He is bright and clever. He really understands you boys very well. It is therefore in your interest not only to accept his influence when he gives it but you must search him out, draw Torah from him, learn from him as much as you can. Exploit Reb Sheftel in all ways so long as you are near to him.

Therefore, I advise you, my son, to get closer to him. Show him that you are interested in being close to him, to learn from him; “encourage him to it.” Go so far as to ask him to give you a shiur in Yoreh Dei’ah. Request his advice in general subjects and certainly in spiritual matters. You will gain from every detail that you will learn from him. If you do these things, you will get closer to the goals you set for yourself.

Eventually, the talmidim acclimated to Rav Sheftel and became close students, who relished his daily shiur. Still, it was a different relationship from the one they shared with Rav Levenberg, who by then spoke a good English and even drove his own car around town, unusual for a European-born Rav. (Although one New Haven native humorously recalled that Rav Levenberg was, as he bluntly put it, “a terrible driver. After yet another near accident he would say, ‘Had I put another coat of paint on my car I would have crashed’ — that is how close he got to crashing.”)

The Vishker Illui

Rav Yaakov Dov Safsal (1888–1968) was born in Dvinsk, Latvia, to Rav Refoel Minkin, a shochet who served in both Dvinsk and the neighboring village of Vishka. Due to financial struggles, Rav Refoel traveled to the United States in hopes of earning a better living, leaving young Yaakov to be raised by his uncles, Rav Baruch Zev Minkin of Grieva and Rav Dovid Minkin of Dubines.

The boy’s genius was apparent from a tender age. In the approbation of Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin to Part I of the work Divrei Yaakov, he writes, “It is difficult to find an illui of that stature, for in addition to other things, he was able to learn 50 or 60 pages of Gemara in one hour. I heard directly from Rav Leizer Silver, who in turn heard directly from Rav Chaim Ozer, who was an expert in the world of the illuyim, as they would all come to talk to him, that he (Rav Eliezer Silver) asked Rav Chaim Ozer to name the greatest illui in the yeshivah world. Rav Chaim Ozer thought for a moment and said that Rav Yaakov Safsal is without a doubt the greatest illui among the illuyim.”

Growing up near Dvinsk, the Vishker Illui was a regular sight in the home of both Rav Meir Simcha (the Ohr Sameach) and Rav Yosef Rosen, the Rogatchover Gaon. He studied under the Chofetz Chaim in Radin, who would invite him for Shabbos and delight in his recitations of Gemara with Rashi and Tosafos by heart; Rav Refoel Shapiro in Volozhin; Rav Chaim Soloveitchik in Brisk; Rav Chaim Ozer in Vilna; Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer in Slutzk; Rav Eliezer Gordon and Rav Chaim Rabinowitz in Telz; Rav Eliyahu Baruch Kamai in Mir; Rav Baruch Ber Leibowitz and Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein in Slabodka; and Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Rabinowitz in Ponevezh. In eight years, he returned home only once.

The Vishker Illui is quoted numerous times by Rav Baruch Ber in his sefer Birchas Shmuel. In Kamenitz, he would complete pages of Gemara in mere minutes, retaining it all in his phenomenal memory. The other bochurim would marvel at his ability to ace the “pin test,” a challenge that involved sticking a needle through the pages of a Gemara, where he proved he could identify the pierced word on any page, even 100 dapim away.

A Slabodka contemporary described Rav Yaakov’s unique intensity: “The Vishker fellow, then a young man of 15 or 16 years, was known for his mastery of Torah. At nine years old, when he came to the Slabodka Yeshivah, he could already explain Bava Kamma, Bava Metzia, and Bava Basra — all three tractates by heart, summarizing the Gemara with Rashi…. He would then sit for hours on end, locked in position with his fist on his forehead, eyes closed, and it seemed as if he was dreaming. But only someone with a particularly sharp insight could see that something was churning inside him, a storm was brewing within. This is how the Vishker would leaf through the entire Shas in his mind, soaring through it like an eagle over the sea of the Talmud….”

In 1909, Rav Yaakov immigrated to America, where his family had settled, but soon after arriving, he decided to return to his treasured yeshivos back in Europe. He was arrested by the Germans during World War I, but freed with the help of Rav Chaim Ozer. In 1921, he returned to the US, joining the faculty of New Haven Yeshivah under the leadership of his friend Rav Yehuda Levenberg.

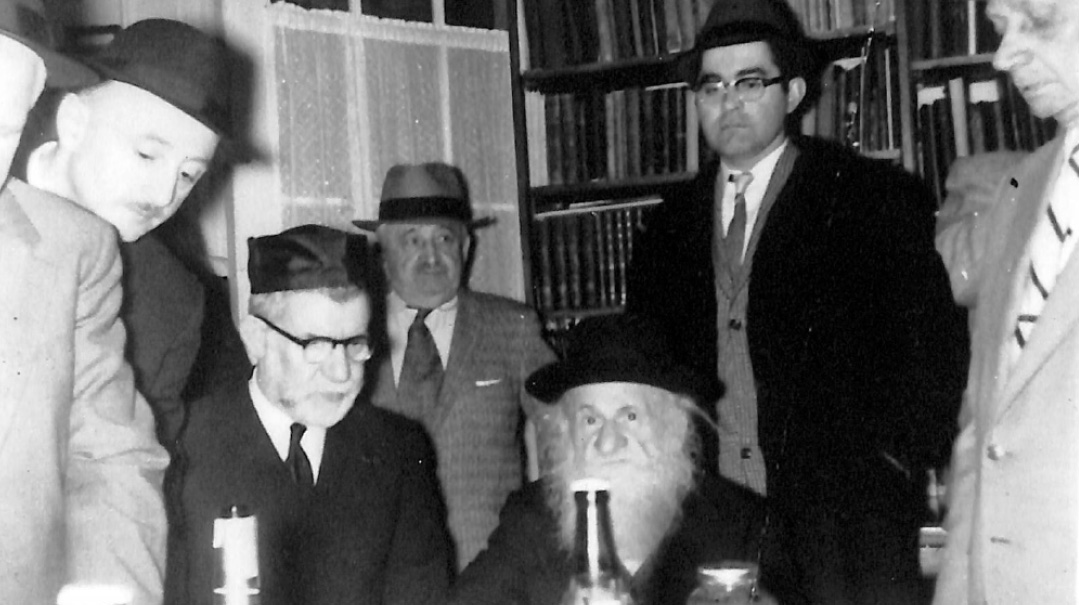

At the bris of Zechariah Schneider in the Bronx in 1962. The Zeide, Rav Moshe Schneider (left) and the sandek, the Vishker Illui

Tragedy struck in 1925 when his wife, Leah (née Greene), a Lithuanian-born New Haven resident, passed away shortly after giving birth. The bereaved Rav Yaakov moved to Colchester, Connecticut, serving as rav and teaching children in the farming community before relocating to New York around 1930, where he remained for the rest of his life.

In 1931, Reb Yaakov Yosef Herman and his wife, who regularly hosted him at their home, suggested a shidduch: Nechama Garfinkel, who had come to New York from Minsk.

In New York, the Vishker Illui held no official position but was revered throughout the Torah world. Torah scholars who wished to speak to him knew to find him at a unique institution, Agudas Anshei Maamad U’beis Vaad Lachachomim on the Lower East Side. When the Mir Yeshiva arrived from Shanghai after the war, Torah giants like Rav Nochum Partzovitz would come speak with him for hours.

In the summers, he could be seen writing chiddushim at lightning speed while riding the subway to Far Rockaway, where family members resided. He insisted on standing during those train rides, due to concerns of shatnez in the seats.

His uncompromising standards were legendary. Once, upon discovering that the rabbi who had offered him a ride presided over a shul lacking a mechitzah, he jumped out of the moving car. He was so attached to Torah, that on Tishah B’Av, he would hold a rubber shoe all day as a reminder not to learn.

When Rav Shlomo Heiman fell ill, he petitioned the Vishker Illui to pray for him. Additionally, when Rav Reuven Grozovsky’s wife, the daughter of Rav Boruch Ber, fell ill, he sent a messenger to the Illui with the message that “the Rebbe’s daughter is sick.”

The Vishker Illui loved talking in learning with the local yeshivah students, often traveling for hours by train to answer a question a bochur posed to him. When Rav Mordechai Elefant of the Itri Yeshiva was a student, he traveled together with his rebbi, Rav Leib Malin, to the Lower East Side to purchase arba minim. Upon being seen by Rav Yaakov, the latter walked over to him, and without any sort of greeting, asked him a question of the Minchas Chinuch and abruptly left. One year later, Rav Mordechai returned to the East Side with Rav Leib, and again Rav Yaakov came over to him and, again without any introduction, said “di teretz is azei — the answer is like this….”

In his memoir, Rabbi Marvin Hier recalls his encounters with the Illui while he was a student at RJJ:

Whenever the yeshivah’s main study hall was crowded, I walked across the street to the small Agudas Anshei Maamad shul, where Reb Yaakov sat and learned. Then in his late seventies, Reb Yaakov was a diminutive man, hunched and thin. But his mind was expansive. My yeshivah friends and I would often test Reb Yaakov’s memory by pretending to have forgotten a Talmudic source. Each time, completely unprepared, he precisely quoted the passage we were referencing, as if he had studied it the day before.

Taking advantage of the special relationship I developed with Rav Safsal, I decided to test the widely held belief that Reb Yaakov concentrated his studies on the early Talmudic commentaries, and ignored the later ones. I selected a question posed by one of the great late commentators, and presented it, as if my own, to Reb Yaakov.

He quickly digested the question, and began pacing the beis medrash, deep in concentration. After several minutes, he walked toward me and declared, “Write your address on a piece of paper. When I have time, I will send you an answer.” For the next ten years, Reb Yaakov sent me dozens of letters in response to my question.

At his levayah in the summer of 1968, Rav Moshe Feinstein delivered a hesped that perfectly summed up who the Vishker Illui was: