Hidden in Plain Sight

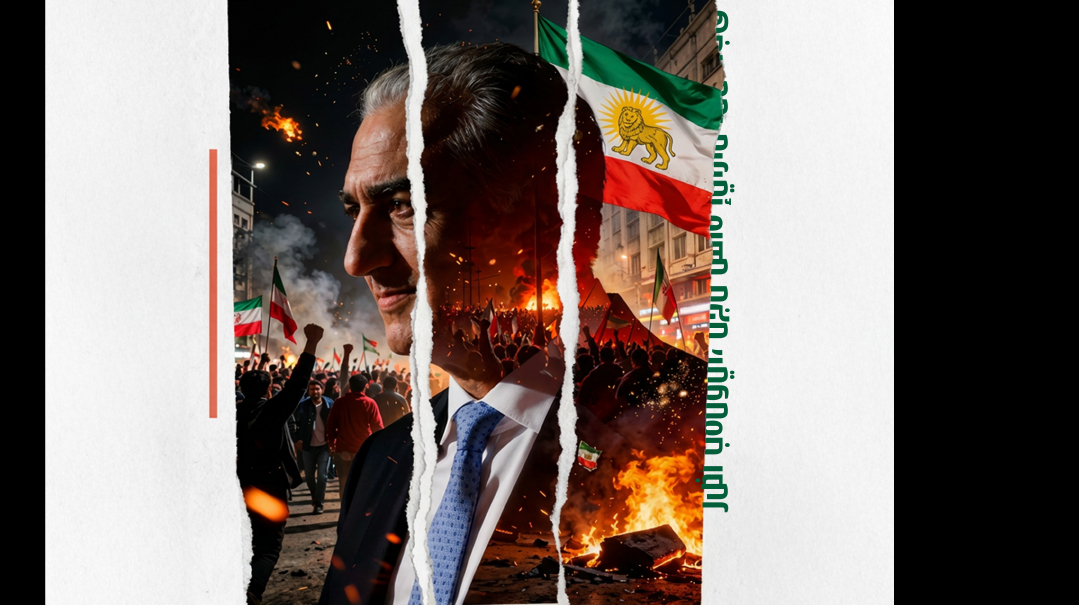

| April 16, 2024Why have crowds begun to converge on an obscure grave in New Jersey?

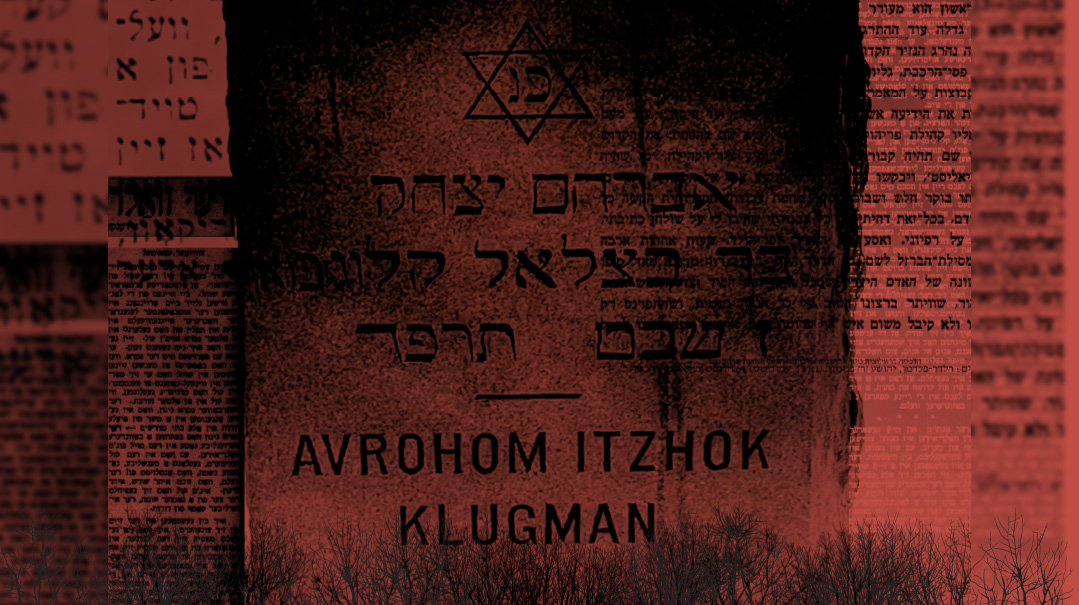

For close to a hundred years, the grave in the Freehold cemetery stood forlorn. Why, then, have the crowds begun to converge on this obscure burial site now? The answer is in a recent revelation: It’s the final resting place of Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Klugman, known during his lifetime as a filthy, eccentric vagabond who lived in the forest, but later discovered to be one of the hidden tzaddikim of the century

One frigid day in January, a small crowd gathered at the Freehold Hebrew Benefit Cemetery, 15 miles from Lakewood, New Jersey, at a small kever oddly situated on the periphery of the cemetery. From shkiah through the long, still night and into the next day, men bundled in long coats and gloves made their way over to whisper a kapitel of Tehillim. They traveled from as close as Lakewood and as far away as New Square to daven at a gravesite that had been situated there for exactly a century.

But for most of those 100 years, the kever stood forlorn, with nary a visitor, year after lonely year. Recently, though, reports began circulating: This was the burial site of an incredibly holy and pious Jew, Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Klugman, known as the Hidden Tzaddik of Freehold.

As scarce details of his life started to emerge, people began to flock to Freehold to daven at the resting place of this unusual oved Hashem. The crowds grew so large that the cemetery’s owners erected a small tent with light refreshments nearby to provide respite from the brutal temperatures, as well as a noisy generator-powered light tower to illuminate the long, dark night.

Who is this tzaddik, and why are people flocking to his kever now?

In recent years, the crowds converging on this forgotten tzaddik nistar became so large that a tent was erected at the site

Like the discovery of the kever itself, Rabbi Klugman’s story is shrouded in mystery.

It began in Lakewood, New Jersey, of all places, some 100 years ago, when on 8 Shevat 5684/January 14, 1924, the Jewish community awoke to devastating news. A machinist working on a train that traversed the tracks running through the town discovered, to his shock, a bloodstained yarmulke stuck to the locomotive’s railing. The shaken Pennsylvania Railroad Co. employee notified his superior, who quickly sent a team to investigate. Equipped with lanterns, the men searched the tracks, and about 12 miles from Freehold, a town just 30 minutes north of Lakewood, workers finally spotted the mangled body of a man dressed in rags.

He was clutching a bundle that contained a Tanya, a Maseches Sanhedrin, a Sefer Habris (a compendium of scientific knowledge and Kabbalah), a siddur, a tallis, and two single dollar bills. Apparently, the deceased had been walking near the tracks and did not notice the approaching train, which sideswiped and killed him instantly. From the belongings in the man’s possession, he was clearly a Jew, and soon, he was identified as Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak Klugman.

Until that day in 1924, little was known about Rabbi Klugman other than that he was a holy, homeless Yid who had spent more than a decade roaming the forests in the area clad in his tallis and tefillin, sporting overgrown hair and a long, crusty beard that concealed his old and tattered clothing. When temperatures dropped to freezing, locals knew he would stop at one of the shuls, where he’d sit and continue his learning unabated.

The Der Tog newspaper that reported on his death encapsulated what the locals knew about him in its headline: “The mysterious Forest Man, who spent his days immersed in Torah and fasting, found dead in New Jersey forest.”

Yet the day that the body of the Der Vald Mensch [The Forest Man] was discovered was also the day the Jewish community found out that Rabbi Klugman was hardly just another homeless vagabond who had lost his mind; in fact, he was a lofty man whose sublime soul soared to unimaginable heights, despite — or perhaps, because of — his unbecoming appearance.

Der Vald Mensch was a hidden tzaddik.

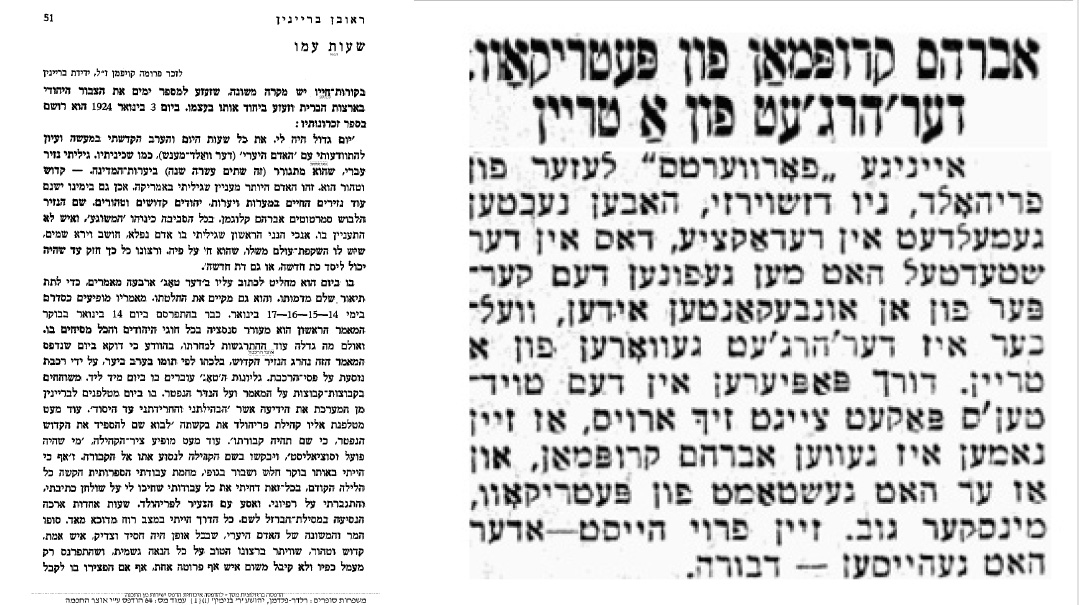

The stunning revelation came from an unlikely source: a journalist by the name of Reuven Breinin. Breinin was born to religious parents in Belarus in 1862 and raised in the Pale of Settlement, where he was recognized as an illui and a budding talmid chacham. At the time, the Haskalah movement was at its peak and ravaging traditional European Jewry; Breinin was ensnared and he all but left Torah observance by the time he was 16. Breinin became a textbook maskil, making a name for himself as an author, a thinker, and a Zionist activist, though he was not quite as acrimonious toward religion as some of the other maskilim of his day.

In 1888, Breinin married Masha Amsterdam from Vitsyebsk, Belarus, a modern, sophisticated woman who had similarly strayed from religion. Breinin and his young family pursued their literary and Zionist activities, which took them around the globe. They moved from Russia to Berlin and then Vienna, after which they made their way to Montreal in 1912. There, he established his own newspaper and hobnobbed with fellow European intellectuals. After a business fallout, Breinin relocated yet again, this time to New York City, where he became a respected writer for the widely circulated secular Yiddish newspaper, Der Tog.

Back then, well before it developed into the famed Torah stronghold it is today, Lakewood was known for the resort hotels that dotted its expanse, and many of New York’s Jews traveled there for respite from the hustle and bustle of the city. Breinin frequented the vacation destination, and one time while visiting, he heard rumors about a mysterious, bearded European immigrant wrapped in a tallis who spent his days isolated in the forest, occasionally making an appearance in the local shul but studiously avoided engaging with humanity while there. He had first been spotted around 1912, arousing the curiosity of both locals and visitors. After repeatedly rebuffing all overtures, the man was written off as a meshugene, and people paid him little attention, which is exactly what he seemed to want.

Breinin’s curiosity was piqued, and he was determined to find out more. It was a formidable task that would take days of dogged determination and cajoling, but eventually the journalist was able to gain some insights into this mysterious personality, and he compiled a comprehensive four-part series about the Vald Mensch in Der Tog.

In a bizarre turn of events, the discovery of Rabbi Klugman’s body the day the first account was published ensured that Breinin’s subject forever avoided the human adulation he so desperately eschewed during his lifetime.

This is his story.

Breinin began his first article with the bit of background he was able to cull together, which wasn’t much.

No one knows his name, his history, his life story, and he avoids every conversation, every answer to the questions he is asked. No one knows what he is looking for, why he is doing this to himself, and why he isolates himself from the outside world and from other people. He is often seen in the forest, wrapped in a tallis, sitting and learning. In the bundle that he carries with him, there are no clothes, no shirts (he never wears a shirt on his skin at all). He carries only seforim with him, and he learns from them in the forest.

The man’s isolation from society wasn’t incidental – he insisted it had to be that way. As Breinin noted:

The wandering, dirty tramp takes no donations from anyone, not a garment, no food, no matter how much they plead with him. He never travels by train or wagon; his feet are swollen, and yet, he never wants to take a seat in a wagon. He even refuses if someone offers to take him from one city to the next in an automobile.

When the weather was warm, and even in the autumn and winter months, as long as the cold was tolerable, the mysterious man spent his time in the forests, people told Breinin. From time to time, he would come to a beis medrash in one of the Jewish towns, including Lakewood, for a day or two. He would slip inside, take a seat, and learn for the next 24 to 48 hours, after which he departed, heading back to the forests for some more learning.

His interaction with others in the shul was very limited, only when he would sell a Jewish calendar or a packet of tzitzis he had spun, which he then inserted into a tallis or arba kanfos. He took a few cents for his merchandise. When someone gave him more, he refused to accept it – and woe to the person who insisted.

Some of the Jews told me that they had tried to give him dollars or meals, clothes, and suchlike, but he absolutely refused to accept any of it. It made him very angry. He came to the batei medrash unannounced, and went almost unnoticed; he sat and learned day and night. Likewise unnoticed, he slipped out of the shul.

The Vald Mensch’s erratic behavior continued for over a decade, and eventually people simply stopped wondering and accepted it.

I am the first one to take an interest in the frum tramp and lamdan, I am told. I asked the shul Yidden, “Why do you think this wonderful Jew is crazy?” The unanimous answer was, “Would a sane person spend his time in the forest, not wearing a shirt, afflicting himself, eating a few potatoes after a fast, or a piece of bread with water? Would a sane person not take money that is being given to him? Would a sane person, when he is found half frozen and starving, not let anyone help him so that he can freeze and starve even more?”

Despite the admittedly strange behavior, dress, and schedule, something didn’t add up. This man’s learning never ceased, and the holy words of Torah were constantly on his lips. Breinin, an inquisitive thinker, was unwilling to ascribe to the prevailing notion that Rabbi Klugman was just another unfortunate soul. Ever the astute journalist, he was determined to investigate further.

One winter morning in 1914, Breinin struck gold: Someone informed him that the object of his strange fascination had turned up at the local shul. He hurried over, and indeed, the Vald Mensch was there, wrapped in his tallis and tefillin, learning aloud and completely oblivious to his surroundings. When he noticed that people had started arriving for davening, the Vald Mensch moved toward the back of the shul and continued swaying over his Gemara. Breinin inched closer, trying to get a better look. But before he even had a chance to see his face, Breinin heard his voice.

Later, he wrote:

His voice rang melancholy, like the sound in an old ruin, the old Gemara niggun [used] throughout the generations in all batei medrash. This niggun took on a unique note when sung by this forest man – and the voice had a tremor… [like] a human neshamah running away from the world, seeking its root, its tikkun. The voice conveyed the pain of a whole nation, the constant conflicts of the generations.

Not wanting to disturb the man’s learning, Breinin waited silently, trying to get a glimpse of the learner’s face. His description of what he finally saw was vivid.

I will never forget that face: A very long, gray beard, almost till the gartel… looks like a cluster of snakes wrapped up and nestled inside one another. His face indicates that he is in his forties. [It is]A tender, eidel, white face, but dirty; it is not washed often. At first glance I thought that he was blind, his eyes just two black holes in his face. Then these holes suddenly flashed, a strange luminous fire, and I noticed that the wanderer has two coal-black eyes. Sometimes they shine as if he is blind and sees nothing, and suddenly they flash like lightning, and that is when he sees. They then once again become blind and withdrawn from the world as if they are covered in ash. His chest is bare; he does not wear a shirt. Instead of a gartel, he wears a piece of string tied around his waist. The impression that I got is of someone who had lived for years in the forest, perhaps deep in a cave… It seems as though beneath the dust and dirt, under the rags, hides a refined, rare, wonderful being, a living symbol of a prince. An old-fashioned, chosen Yid, who embodies the galus, the tragedy of a whole nation. I saw for myself the gestalt of someone who wages a great conflict with himself, with the nature around him, with human nature, and strives to prevail over the body and its needs to become purely spiritual.

Breinin was enamored.

A few minutes later, the learning ceased for a moment as the man put away his Gemara to take out his Chok L’Yisroel. Breinin seized the opportunity.

“Shalom aleichem!” Breinin greeted him. “Can I ask you a question?”

The Vald Mensch wasn’t interested, and let him know that in no uncertain terms.

“Avec fun mir!” the man responded irately. “Leave me be… Go to your hotels and revel in your nonsense. What do you have to do with me?”

With that, he pulled his tallis further down his face and lay his head on the table.

All I could see was the tefillin shel rosh. He didn’t move… Suddenly he sat up, turned around to the wall and began reciting Chok l’Yisrael aloud, pesukim from Tanach, quotes from the Gemara, in the voice of someone who wants to win over himself, or is trying to outshout something in him and around him. His voice contained a lot of bitterness. A cry from a wounded soul. Suddenly the voice became sweet, soft, kind and compassionate, and then angry once again, as if he was angry at the whole world, and as if he was trying to cast off…bad spirits and poisonous doubts.

Breinin didn’t give up.

“Reb Yid,” he tried again, “come with me to my hotel. Take something to eat. I have something important I want to speak to you about.”

The Vald Mensch raised his eyes and his voice at once: “I have nothing to speak to anyone about,” he said icily. “You are the Satan, the yetzer hara.”

Breinin wasn’t backing down.

“An erlicher Yid doesn’t speak that way,” he shot back. It wasn’t a very cogent argument.

“I’m not an erlicher Yid,” replied the Vald Mensch. “Leave me be. Why are you looking at me with such awe and respect, as if I was really something? Yidden don’t idolize.”

With that, he went back to his sefer.

A companion who had accompanied Breinin tried giving the Vald Mensch a coin, which was rebuffed as well, but with even more anger than before.

“Go give money to the rebbeim, the rabbanim!” he screamed. “They like the dollars and the cents. They need it. I am not a rebbe or a rav, leave me be. Go to your hotels, make yourselves nuts.”

And with that, he resumed learning.

Breinin backed off and returned to his hotel. His thoughts, however, remained in shul.

The voice, the fantastical gestalt, accompanied me to my hotel. I could not calm down. What kind of Jew is this, a crazy person, a wild person? Is he a baal teshuvah? A former sinner? An unfortunate person who experienced something very tragic? Does he run away from people because they once did something terrible to him? Or is he not running away from people, just seeking something higher? Is he looking for G-d? Is he seeking to be healed? To relieve his hidden spiritual suffering? Is this Yid a batlan, a mixed up mind? Is he a lofty person or a lowly one?

Breinin returned to the shul later that afternoon for Minchah; right after davening, he approached the vald mensch, who was still in his corner, engrossed in learning and studiously avoiding the crowd. But something had changed. Breinin seemed to have won the man’s trust, and when he noticed Breinin, he looked up kindly, speaking both softly and sympathetically. He first apologized for getting angry that morning.

Breinin noted:

He believed that I was one of the Jews who wanted only to take him away from Torah or to speak to him about idle matters. They are Jews who don’t understand him and…won’t let him live the way he wants to.

In the first clue that there was more to the idiosyncratic man than he let on, he astonished Breinin by informing him that he actually had read some of the writer’s Hebrew articles. He understood Breinin’s ideas and concluded that he was a man with whom he could converse, who might be able to understand him.

As they spoke, day turned to dusk, almost time for Maariv. The sky was dark, the lighting was dim, yet the people in the small shul in Lakewood were agog with excitement. Something extraordinary was happening: The Vald Mensch was speaking! Pleasantly! At length! With a stranger! The men gathered at the side of the room, standing silently, desperately trying to overhear the conversation between the modern, sophisticated, non-religious intellectual and the mysterious homeless man who had always avoided contact with those around him.

Their conversation lasted until the wee hours of the morning. At first, Breinin kept his gaze fixed on the other man; he didn’t interrupt him with questions or comments and just let his words pour out. As the crowd dispersed, and the two men became more at ease with one another, Breinin gently challenged some of his more ascetic practices, to which the man responded with intelligence and candor. He also revealed personal details about himself.

What follows are excerpts from Breinin’s report of his captivating conversation.

To my surprise, the stubbornly silent person opened up a wellspring of concepts and ideas, which had been sealed to others for so many years; now, it suddenly opened for me.

His voice was tender, soft, and very heartfelt. It belonged to a person who has no gall, who is loftier than all the nonsense and trivialities of regular life, who is liberated from physical sufferings, from envy, hatred, revenge, of a person who lives cleanly in agreement with G-d and with nature. [It was the voice] of a person who kills his body every day, to strengthen and liberate his soul. And in truth, his Hebrew language was neshamah language, neshamah breathing, and completely spiritual.

Despite the fact that he was wearing dirty rags, his chest was bare, and his face was covered with dust and earth, his face still glowed. You felt the tenderness and refinement of this mysterious being and his pure, beautiful goodness.

I admit that for the first few minutes, I, standing so close, face to face, with the forest man, really suffered aesthetically. However, the longer he spoke to me, the more I felt that this is a Yid that is filled with holiness and purity, a Yid who lives in the pure spheres of his own world.

Before I share what we talked about and the impression he made on me, I want to point out that the Forest Man spoke to me in an excellent Hebrew, like a true talmid chacham, an original thinker. His proper and correct Hebrew was sprinkled with the philosophical terminology of the Rambam and Rav Yehuda Halevi. He cited concise, sharp Hebrew quotes that convinced me right away that this forest man had studied the philosophical works of both chachmei Yisrael and of the non-Jews at length.

Reuven Breinin’s article about Rabbi Klugman came out on January 14, the very day he was found dead on the train tracks

HE initially avoided answering my questions about his personal life. He shared concepts of body and soul, and how the sinning body disturbs the freedom, the progress, of the neshamah. The body is a temporary form, an interchangeable garment, but the being of a person, the soul, is infinite. The neshamah, when it is not enslaved by the body, strives to cleave to G-d… The forest man did not understand and did not want to understand those who were busy only with their physical world and not their obligations to G-d.

I noted that this affliction of the body, not keeping it clean, and avoiding people, doesn’t fit in with the Torah and emunah principles that caution a person to protect his life, health, and hygiene. His conduct is more Indian or Buddhist than Jewish. The Indian philosophy is passive, while the Yiddish weltanschauung is active, creative, and follows the uber-principle of “uvacharta bachayim,” choose life. The nazir listened to me calmly and answered in a soft language: I don’t want to teach anyone how to conduct himself; who am I to do so? I am too little a person to be a leader of others. I am not a mussar giver. I just want people not to disturb me and let me live according to my Yiddishkeit, and my neshamah. Of what use is the cleanliness of the body if the neshamah is sullied? When we look after the external cleanliness of the body, and its imaginary demands, we make it weak, submitting to its every desire and sin, and the bodily sins make the body impure, dirty, disgusting. No soap, washing, or perfume can make it clean. Living with people fills life with envy, hatred, gossip, lies, and suchlike. The air becomes unclean, and full of ailments for the soul.

I told the Forest Man that some of my friends in Lakewood, and the guests who were with me, had expressed their good will to provide him with everything, so that he could sit in the beis medrash and learn however much he wants instead of wandering through the forests and the different towns. It does not reflect well on Yidden that a talmid chacham such as he should walk around dirty, without a shirt, in the forests, I noted. My friends want to care for him with dignity.

He responded angrily: The hunger, the suffering — there are so many good Jews, geonim and kedoshim, and no one takes care of them. Let your friends help those great people with their needs. I am a simple Jew, a small person. I can earn my bread, I can work, I make tzitzis, I sell a few calendars, and I have, thank G-d, for all my needs. In the forest there is clean air, and every blade of grass says praise to Hashem. For me, it is good as I live now. When it becomes cold in the forest, or I become bothered by people, I come to the beis medrash and look into a sefer. Why should your people be busy with me? Let them worry about their own poor, thirsty neshamos.

How can you sustain such a life? I countered. You are making yourself sick and you’re killing your body. I see that you are weak. Where is the uvacharta bachayim? His answer was, Baruch hanosein laya’eif koach, blessed is G-d Who gives to each person strength. Thank G-d, I am healthy. I wonder the opposite: How do people manage in the hotels, where they eat so much, and look for every way to stuff their bodies? It’s hard work, nebach. I have pity on those people. They are starving and weakening their neshamos.

The forest man said all of this with such simplicity, with such naiveté, and such heartfelt, pure words, and no doubts could crack his confidence in his pure Yiddishe menschlichkeit.

I noted to the Forest Man that his Hebrew language and the concepts that he was sharing convinced me that he was familiar with philosophical works from various eras, and that he was well-read in modern Hebrew literature. I wanted to know how, then, he had become a forest person who comes to the beis medrash, who keeps all 613 mitzvos.

During the course of the conversation, I won over his confidence and he revealed to me that his name is Avraham Klugman, from Pietrkov, Minsker district. I could not extract details about his background. He did hint something about a family tragedy, but he didn’t talk about it. The nazir let on that prior to that, he had read a lot of philosophical and modern Hebrew literature, but it is almost twelve years since he threw it all away… and came back to the Tanach, Talmud, Mishnah and the other holy seforim.

I want to share an excerpt of his conversation with me, word for word, translated from Hebrew: “I tried to adapt myself to my generation, and to the current world and to look like I was living like all the maskilim, the so-called cultured people. But it didn’t work. I can’t breathe in this cultural sphere of today. The lies stifle me. The constant pursuit of money, of empty pleasures, are for me simply unfathomable. It made me sick, and I had to run away from today’s people and from the urban culture. The emunah in Hashem, the Yiddishe Torah, our precious tefillos, the Gemara, made me healthy, and Hashem helped me free myself from the world’s nonsense. I don’t want to know what the world thinks, what people say. I hear better what my neshamah, G-d’s light, tells me. I could answer your words, but I did not come to America to debate and to prove this to others. The day is short and the work is plenty, G-d knows how long it is bashert for me to live, possibly only one day, one hour, and therefore, I want to carry out my mission to G-d and to my soul far from the sinning atmosphere.”

I tried further to dissuade the nazir from his lifestyle of living in the forest, and to convince him to put on proper, clean clothes. To this, he answered: “Ki lo machshevosai – my thoughts are not like your thoughts, and my ways are not like your ways.” [He said]: I don’t want to say chalilah, that my ideas are loftier than yours, that my ways are the only right ways. But I cannot think the way others think, and it is absolutely impossible for me to go in your ways. I am on a lower level than you, the wanderer declared in a mild-mannered way.

You can all live in New York, and breathe its air, and stay clean, happy and calm in the unrest. I cannot do this and I don’t want to know how. I could not stay in New York for one day, where the air is infested with nonsensical olam hazeh, where everyone is pursuing more and more… yet no one knows what he is chasing after and what others are chasing after. I am an egoist, a maven on a good piece of merchandise. I cannot sell chayei olam, eternal life, for such a cheap, nonsensical price of chayei sha’ah, momentary life. For a fattier, better lunch, for a bit of dumb honor, and other nonsensical things.

I am a simple Jew, and I can’t draw out the sparks of kedushah from the opposite of holiness. Can you do this? Then good for you. I am an egoist, and I have pleasure when I daven with kavanah, when I learn a piece of Gemara, when I see G-d’s Hand in everything. Perhaps you serve G-d on a higher and nicer level than I do, but I cannot do it.

You are pursuing… a better life, but you find death. I seek death – the death of the body. I don’t want to die before my time, chalilah, as long as G-d grants me life. And… I must use this life to prepare the neshamah for eternal life. I want to keep the neshamah as clean as I got it. And the more I seek the death of the coarse materialism, of the wild and childish inclinations in me, the more life I find for my neshamah. I don’t want to convince myself that I am worthy of eternal life, and it would be a chutzpah to demand such a thing, then what have I accomplished during my life for the life of others? ”

The riveting conversation lasted several hours; it was just the two of them, and Breinin sat entranced. Finally, it was time to bid farewell. But the man had just bared the depths of his soul, so Breinin gently suggested that perhaps just this one time, Rabbi Klugman could accompany him to the hotel, and they could enjoy a cup of hot tea.

Rabbi Klugman actually thought about it for a minute — but firmly rejected the offer.

“This hour that we spent speaking was very precious,” he said. “I have yearned for this for a long time. Since my younger years, I have retained a fondness for your writing. But I cannot go with you. It would take me too far off my path.”

With that, Rabbi Klugman and Breinin warmly shook hands and took leave of one another. Rabbi Klugman promptly turned back to his beloved Gemara, resuming his poignant niggun, and Breinin made his way to his hotel. It was 3 a.m., and he walked through the dark, quiet streets of Lakewood, his mind racing as he tried to process what he had heard.

In keeping with his profession, Breinin carefully documented his interaction with the Vald Mensch. He filled page after page with his gripping account before sending it off to his editorial team at Der Tog. They decided to publish the piece that month, in installments over four consecutive days.

The first would be printed on Monday, January 14 – but as newspapers hit the stands Monday morning, Rabbi Klugman’s story prominently featured on the cover page, his mangled body was discovered.

The niftar was taken to the Talmud Torah of Freehold, where the chevra kaddisha performed a taharah. Meanwhile, the revelation that Rabbi Klugman was a tzaddik nistar stunned the community, and people clamored for that morning’s Der Tog, so they could read Breinin’s feature-turned-eulogy.

According to newspaper clippings from the Forward and Der Tog, the mournful levayah was large and impressive, drawing not just locals but also people from neighboring communities. A shocked Reuven Breinin, the writer who had exposed this tzaddik nistar to the world, traveled in from New York.

An article in Der Tog, printed alongside Breinin’s second installment the next day, noted that a reporter was present at the levayah – as were a son and daughter of Rabbi Klugman from New York. The article further revealed that “more family members had missed the train.”

The fact that Rabbi Klugman had children was in itself a surprise to the Lakewood community. How these family members found out about their father’s passing remains a mystery to this day. According to the reporter who spoke to the children, Rabbi Klugman had nine children, and they were the only two to come with him to America. His wife Devorah and seven children remained behind in Russia (a note found in the back of his siddur, which was in his bag at the time of his demise, corroborated this information).

The children briefly told the reporter that their “father loved them very much, but could not help them,” and that “for the whole time, he [was in America, he] did not send them even one cent.” They revealed that he struggled to make ends meet as a melamed in Russia and distributed his meager earnings among poor people. They talked to the reporter about his visits to New York every six months “to see his relatives,” and that at first, “he would speak like a smart person,” but then, “he began to speak in a way that didn’t make sense.” The last time their father was in the city was the previous July. His daughter said she would give him a few dollars, which he agreed to take, but he declined to eat or drink. He didn’t take any clothes, nor would he lie on a bed his daughter had prepared for him, preferring to sleep on the floor.

That summed up the information the reporter gleaned from his children, and he then went on to describe the levayah as both mournful and impressive. Two hespedim were delivered, one by Reuven Breinin and the other by an unnamed rav from Lakewood.

When it came time to bury the tzaddik, the two groups that owned Freehold’s adjacent Jewish cemeteries vied for the merit of having Rabbi Klugman buried in one of their plots. The newspaper reported that eventually, the two groups — “the workers’ branch” and “the Orthodox union” — came to a compromise: the tzaddik would be laid to rest on the border between their fields, with the portion of the coffin containing Rabbi Klugman’s head interred in the Orthodox union’s cemetery, and the feet in the worker’s branch portion. The niftar was interred on the periphery of the cemeteries — an area usually reserved for children, r”l —thus assuring that both groups would play host to this tzaddik, and that a pure neshamah would be surrounded by similarly unsullied souls.

For the next 70 years, the kever of the hidden tzaddik remained forlorn and forgotten, with nary a visitor. It took a Holocaust across the ocean to spawn mass migration from Europe to the United States, which in turn led to the establishment of a small yeshivah in Lakewood, a new generation of litvishe bnei Torah captivated by kivrei tzaddikim, and a change in cemetery ownership for the kever to become known to the public.

The precise story of how and when the kever was discovered is almost as mysterious as the tzaddik himself; to this day, details remain murky. The first account of the kever’s discovery known to this writer was that of Rav Dovid Thumim, a member of Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha kollel.

Rav Thumim was an erudite talmid chacham and kashrus expert who learned 18 hours a day and utilized the yeshivah’s summer bein hazmanim break to oversee complex kashrus operations in far-away food production facilities. He had an incredibly wide range of knowledge and enjoyed researching different eras by delving into historical records.

According to his son, Mr. Heshy Thumim of Lakewood, about 45 years ago, his father came across the Der Tog newspaper clippings by Reuven Breinin. Astounded to discover that such a tzaddik was buried relatively nearby, he researched official documents from that time period with the last name Klugman and found several records that matched the information in the Breinin article.

Rav Thumim managed to contact Rabbi Klugman’s daughter, who was living alone in New York. Heshy doesn’t know how his father found her information; possibly via the discovery of a wrongful death lawsuit filed against the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. by two relatives of a decedent named “Abraham Issak Klugman,” the English spelling of his name. The suit, filed in the Surrogate’s Court of New York by a son and daughter of Klugman, mentioned that the decedent died near Freehold, New Jersey. The paperwork submitted to the court had an address for each plaintiff, and while the son (Charles, according to the lawsuit) passed away in 1980, the daughter (Bertha) was still living. (She has since passed away.)

About five years after discovering the tzaddik, Rav Thumim traveled to meet Bertha, who was quite elderly by then. As far as Rav Thumim could tell, she seemed observant, albeit far from the intense religiosity of her father. She was happy to meet Rav Thumim and recounted what she recalled about her saintly father: a chassidishe rebbe near her father’s hometown encouraged him to emigrate to America because his greatness was such that it had to be concealed. When the family arrived, she, Charles, and their mother headed for New York, while Rav Klugman went to Lakewood. Bertha didn’t explain why her father left the family, but she did hold him in great esteem and told Rav Thumim that he was a tzaddik nistar.

Tragically, Rav Thumim perished in a plane crash in 1999 en route to inspect a food plant in Ecuador. Due to their relative youth at the time of their father’s passing, the Thumim children didn’t know the details of his conversation with Bertha or even the location of the kever.

“As a child, I remember hearing that my father spoke glowingly about a particular kever in Freehold and encouraged people who needed a yeshuah to daven there. My siblings also spoke about vague recollections of our father going to the kever in Freehold on Erev Rosh Hashanah, but we didn’t know any more details,” says Heshy, the second-to-youngest of the seven Thumim children.

But unbeknownst to the Thumim children, others did know about the kever.

On an autumn day in 2015, Heshy found himself davening at Minyan Shelanu, a shul and social center serving disenfranchised teenagers in the Lakewood area. He volunteers there, and was helping himself to a coffee after Shacharis when he noticed a fellow mispallel at the minyan eyeing the name on his tallis bag. The mispallel — Rabbi Yosef Gluck — hesitantly approached him and introduced himself. He then proceeded to ask Heshy if he was related to Rabbi Thumim, the talmid chacaham and kashrus expert who tragically passed away.

“Yes,” replied Heshy. “Why do you ask?”

Rabbi Gluck explained that he had heard about a kever of a tzaddik nistar in the Freehold cemetery from his rosh kollel, Rav Shlomo Pollak of Lakewood, and had even visited it a few times, but he was unfamiliar with the details of the tzaddik’s life. He remembered someone mentioning that a Rabbi Thumim of Lakewood was familiar with the story.

“Are you related to that Thumim?” he wanted to know.

Heshy nearly dropped his coffee; someone else knew about the tzaddik! He asked Rabbi Gluck for the location and notified his family.

The tzaddik’s next yahrtzeit was January of 2016, and Heshy and Rabbi Gluck planned a trip to the kever together. At this point, they knew the barebones of his story and the location of his kever, but they were still in the dark when it came to details.

“Other than the memories that my siblings had of my father coming to the kever and holding it in high esteem, we really didn’t have any information to work with,” remembers Heshy.

Three years later, in 2019, Rabbi Gluck was in the area. He decided to pay yet another visit to the forlorn kever in the quiet cemetery, but when he arrived, there was another Yid there: Rabbi Aharon Feder, a Skverer chassid and researcher who had independently discovered the tzaddik a few years earlier. He supplied Rabbi Gluck with the newspaper clippings that the family had vaguely remembered hearing about — and a clearer picture started to emerge.

Last year, the cemetery’s operating society sought to retire. It had been established 109 years earlier and had some second-generation members, but activities were dwindling. They began looking for a buyer for the cemetery, which still had some 4,000 plots available, and the board considered several offers from non-Orthodox and non-Jewish groups.

Then a group of Lakewood bnei Torah met with the trustees. They noted that the society’s bylaws stated that the cemetery must be perpetually governed by halachah, and if transferred to a group whose members were personally unfaithful to Torah and mitzvos, there was little to no hope that the cemetery would be managed according to its founders’ intent.

The Lakewood group made an offer on the cemetery and, buoyed by the opportunity to keep it in faithful hands, the officers voted in favor of their proposal. In November of 2023, ownership of the cemetery transferred to the group. It was just one month shy of the tzaddik’s 100th yahrtzeit, when crowds would flock to the perpendicularly placed kever on the periphery of the two sections.

A new generation of American Torah Jewry would have the opportunity to daven at the kever of a tzaddik who sanctified its soil a century earlier.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.