Behind the Scenes

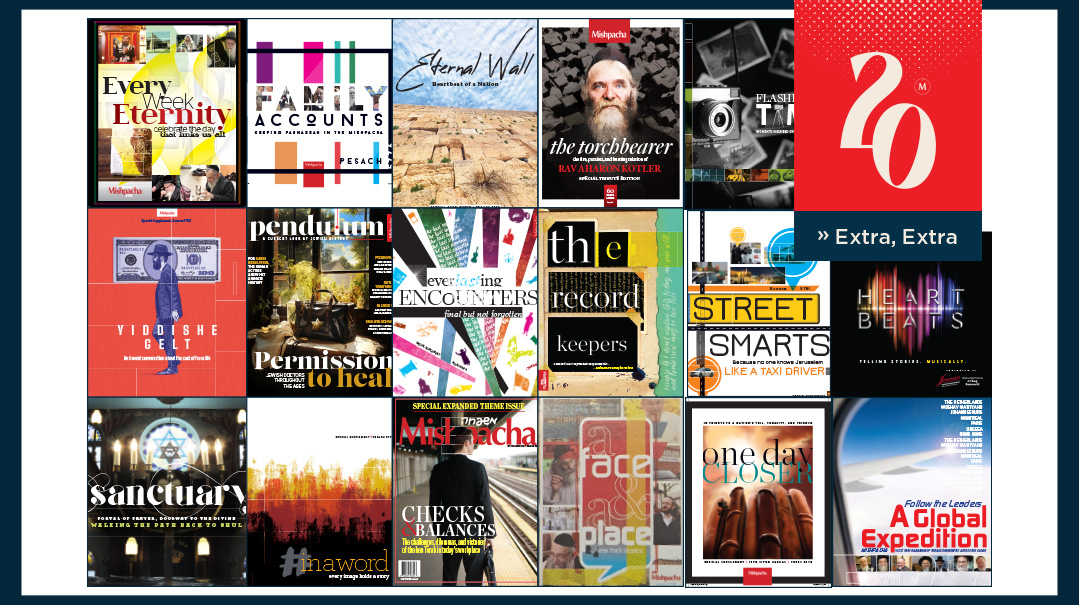

Mishpacha insiders know that the creative process is often a lot messier than the polished final product

When you get your weekly Mishpacha package, it’s perfectly bound and wrapped, with every i (hopefully) dotted and every t neatly crossed. But the insiders know that the creative process is often a lot messier than the polished final product. What kind of challenges, misadventures, and occasional heartache are weathered behind the scenes to produce your weekly Shabbos reading?

As It Happened

Rav Ovadia Yosef was niftar on a Monday, after the weekly magazine had already gone to print. We all got a call to come back to the office, to produce a special tribute supplement – while the levayah was taking place.

Usually the art studio imports ready text into our programs as we design articles, but this time we inverted the process. Our art team quickly built a design, collected photos, and began building the “look” of the supplement as our writers and editors were still creating the text.

Our offices at the time were in the Har Hotzvim area, and the historically large crowd flooding Jerusalem for the levayah stretched all the way down Golda Meir Boulevard. As I worked, I could hear the buzz of the procession happening outside, and I really wished I could have been out there with everyone. It’s not every day you see hundreds of thousands of people from different backgrounds coming together like that.

But by the time I wrapped up my work, it was all over. I knew I had my own contribution to make, to help readers appreciate the gadol we’d lost — but I still couldn’t shake the feeling that I’d missed out on something truly significant.

—Menachem Weinreb, art director

Paper Crisis

During Covid, when the world ground to a halt, it became difficult to procure paper. Things reached a point where one week we were stuck with no paper anywhere on the American continent to print the magazine. Dozens of frantic calls to paper companies and brokers got us nowhere. But it isn’t Shabbos without Mishpacha, and we knew we had to come through for our readers. So that week we ended up printing the magazines in Israel, where the printer still had access to paper, and shipping them via air ship. The cost of shipping was $45K — but everyone got to enjoy their Mishpacha that week.

—Avi Lazar, CEO, North America

Step by Step

AS office administrator, my secretarial and bookkeeping responsibilities were augmented by a lot of odd jobs, including arranging a big print order for a travel agency that provided all its clients with a free copy of Mishpacha’s mega Yom Tov edition.

One year, our giant stacks of Succos editions were delivered to the office so I could label and send them out, but the elevator broke — so we needed to go up and down two flights of stairs multiple times, lugging magazines.

Erev Yom Tov was super-hectic. The phones were ringing off the hook with subscribers frantically calling to say they didn’t get their magazines, office employees were picking up magazines for their families, and a little party was taking place, too. On top of this, someone from the travel agency needed to come pick up their order, which was now down in the basement.

A woman finally showed up with a baby carriage — and we used that to transport the magazines! I just hope that in all the chaos, no one made off with more than their fair share.

—Lori Friedman, administrator

The Ultimate Editor

This is a story about stories that never happen. A few weeks ago, I drove down to a Beersheva government office early on Sunday morning for a scoop: to meet a Gazan who had saved many Jews on October 7th.

It would have made a fascinating interview: the man knew Gaza like the back of his hand and had important things to say about the war. But as soon as I got there, I learned that the story would never see print. The man had decided that he wanted to lie low, given that his brother had just been killed by Hamas.

It was disconcerting to have put hours into a dud, but in that eloquent phrase, it was what it was.

I drew a couple of lessons. One, that journalism is about the many conversations that don’t go anywhere. They may not result in a column now, but they build you as a more developed writer.

More importantly, it was another example of something that I experience constantly: we have to arrange our thoughts, we say on Yamim Noraim, but ultimately “Me’Hashem ma’aneh lashon” – the final words, or whether indeed there will be final words, are in the hands of the Ultimate Writer.

—Gedalia Guttentag, Editor

Say It In Less

Once I wrote a piece about my brother-in-law Shmulie, a veteran baal Mussaf. Remembering his davening, I started writing about our shul, too. I wrote and wrote and wrote, and it was as cathartic an experience as I had ever had. I wrote through tears, through heartache, and through pain — and when I was finished it was over 1600 words.

I realized that it was too long and went about attempting to cut it down. After much (much) whittling, I finally managed to pare it down to a mere 1100 words and I sent it in to my editor. It came back to me with a kind comment, plus the request that it diet even further to (gulp) 600 words.

And that’s how I learned that if you can’t say it in less, you have no business hitting the keys.

—Sarah Spero

Of Misplaced Modifiers

Oftentimes, when I tell people I’m a proofreader at Mishpacha magazine, I get a confused look. “Oh, that’s nice. So… you put the commas in?”

Oh ho, do I put the commas in. And the colons and semi-colons and ellipses and itals, and make sure the sentences are parallel and fact-check and consult the Style Guide and, and, and!

I mean, have you even seen the Chicago Manual of Style? It’s, like, 1,000 pages long! So numerous are the ins and outs of punctuation that, oftentimes, my fellow addicts to grammar (a.k.a. coworkers) and I spend 20 minutes debating a single misplaced modifier.

So the next time you read one of Mishpacha’s beautifully written articles, I encourage you to stop at a punctuation mark and remark to yourself, or those in your vicinity, “Wow, what a properly placed period.”

—Chaya Leeder

After the Last Minute

AS a production manager at Mishpacha, one of my tasks was to upload the pages of each edition of Mishpacha Junior to the printers. Unlike the main magazine and Family First, the children’s magazines do not include ads, and we can therefore send them to print as soon as the content is ready.

This means that before the Yom Tov crush, we tried to send a month’s worth of Mishpacha Junior to the printer in advance. One year I sent about five weeks of magazines to the printer shortly before Purim. It was a complex operation but our team worked hard and got it all done, so I could send the files to the printer.

Then, about an hour before krias Megillah on Purim night, I got a call from Wendy, our print coordinator in the US. “Esti,” she said, “you sent me the wrong chapter of the back comic in one of the magazines!” Apparently she followed the comic every week, and she realized we’d sent the wrong file.

What to do? No one was at the office, or even reachable at this late hour. I definitely couldn’t run back to the office. I phoned the comic’s illustrator, who had a copy of the correct chapter at home, and sent that off to Wendy, who swapped it into place. I went into Purim with my heart racing — but knowing that our mission was accomplished.

—Esti Krainess

A Yom Tov-Shaped Hole

One year, in honor of Yom Tov, we planned an exclusive tour at a very interesting factory for the readers of Mishpacha Junior — complete with fascinating text and photos. The article was all ready to go to print, when at the last minute, the company decided to pull it. It was a major challenge to fill that space with Yom Tov-worthy material at that late hour. But we did it and I believe the readers still enjoyed a super Yom Tov package.

P.S. One year later, the company changed their minds again and we printed the piece. Moral of the story: Never give up, and remember that each feature has its Divinely ordained timetable.

—Libby Tescher

No Excuses

I recently wrote “Out of Control,” a Family First feature about mothers who have difficulty staying calm with their children. It’s hard to imagine how much effort, thought, research, discussion, self-doubt, and revision goes into producing a piece on such a sensitive topic.

Almost a year and half went by from when we first received the pitch from “Nechamie,” the protagonist of the piece, until it went to print. The writer who was initially assigned to it got cold feet, so it was passed on to me. I didn’t want the pressure of a deadline, so we agreed I would do it slowly, in my “spare time.”

After doing research in psychological journals and newspaper articles and some parenting books and conducting a number of interviews with the protagonist and the experts featured in the piece, and asking myself this question over and over again — how do I create a piece that is sensitive and empowering to the people who are struggling with this terrible challenge while not sounding like I’m excusing the nisayon? — my fellow editors and production managers realized it would never make it to the computer screen if I wasn’t given a deadline.

So I was given one. The third of September, 2023, in time for the Succos issue.

A deadline at the beginning of September means writing during school vacation. While trying to fit in my regular editing tasks and regular housekeeping tasks alongside entertaining my children, who by 10 a.m. had already finished all the Mommy Day Camp activities I’d prepared for the day.

It was a very intense summer.

The piece was in fact ready for Succos, but it got bumped because we had too much content. Then the war broke out, and we felt that while there were parents burying their children and mothers and their children in captivity in Gaza, it would be grossly insensitive to run a piece about mothers who lose their tempers with their children.

So we rescheduled it for the Chanukah issue. But when doing their usual review, our rabbinic department expressed concern that the piece normalized parental anger. We scrambled to find a different feature for the Chanukah issue — and went back to the drawing board.

More discussion. More interviews. More consultation with professionals. More gnawing doubt. More rewriting. Restructuring. Deleting and adding.

But we did it in the end.

And our inbox exploded with emails from people thanking us, telling us they felt no longer alone, drowning in shame, and were inspired to seek help — plus some emails from people expressing the concerns we initially had — that we normalized and justified the inexcusable. It’s been a lively and enlightening discussion that has stretched on for months, and we’re still getting letters about this very important issue.

It was well worth the effort.

—Sara Bonchek

Cuba on a Dare and a Dime

MY assignment to Cuba in November 2007 started with a dare accompanied by a few scares.

The dare, of sorts, came from our editor-in-chief, Rabbi Moshe Grylak z”l. During those early years, we would meet weekly and brainstorm for my Jewish Geography (JG) news column.

The JG format included news from far-flung Jewish communities. When I mentioned that Cuba was on my radar, Rabbi Grylak trained his twinkling eyes on me. “Why don’t you go there and report in person?”

I gulped. Cuba was a communist dictatorship. The US and Israel had no formal diplomatic relations with Cuba, so there were no embassies there that could protect me if need be.

I still have memories of the Cuban missile crisis in 1962 when I was a second-grader at Hillel Academy in Passaic. The risk of a nuclear war between the US and Cuba’s sponsor, the Soviet Union, was palpable. We practiced air raid drills where we crouched under our desks and covered our heads with our hands. As an adult living in Miami, I was exposed to the hostility that Miami’s large Cuban expatriate community directed at the Castro regime.

Yet journalism often requires a writer to leave his comfort zone, so I told Rabbi Grylak I’d work on it. I discovered I could enter Cuba on my American passport by flying with a State Department-accredited Travel Service Provider. Entry was normally limited to representatives of humanitarian aid organizations, attendees at professional conferences, and sometimes, journalists with a specific assignment.

That year, the Patronato, Cuba’s Jewish Federation, was holding its 100th anniversary celebration, so Mishpacha’s publisher, Eli Paley, signed a letter on Mishpacha stationery authorizing my assignment. Having traveled for Mishpacha many times, I considered myself a master of travel logistics, yet I made several blunders.

Following email correspondence with Yacob Berezniak, treasurer of Havana’s historic synagogue Adath Israel, I assumed he would host me in his home. First mistake.

I made no provisions for Internet access because I thought I could use the synagogue’s connection. But I discovered that service was sporadic and incompatible with my computer, so I was incommunicado for my three-day trip. Second mistake.

I knew my credit cards wouldn’t work there because the US and Israel had no banking relations with Cuba, and to this day, I thank Chanie Tuchinsky in our US office for making sure I had enough cash to cover my expenses. Barely, as it turned out.

When I checked in for my flight to Havana at Miami International Airport, the travel service provider informed me I owed an additional fee in cash that nobody told me about beforehand. My cash was getting depleted before I even got there.

I arrived in Havana on a Sunday afternoon and took a taxi from the airport to the synagogue. It was chained shut. A curious neighbor across the street saw me. I don’t speak Spanish, and she didn’t speak English. Understanding my predicament, she hurried down the street to Yakob’s apartment. He rushed over and apologized, saying he forgot to tell me the shul is closed on Sundays.

Jewish community members in Havana were mostly elderly, subsisting on food ration coupons in cramped quarters, but Yakob did find me a room in a nearby hostel at $25 a night, and I did bring enough food to last for three days. Yakob also asked the synagogue’s non-Jewish “shamash,” Rey, to be my tour guide and he knew Havana — and Spanish — well.

Cuba was fascinating. Cars in mint physical condition from the 1950s lined muddy, unpaved streets. Historic Havana was charming with little physical evidence of communist oppression, although Rey warned me that I was probably being watched. On my last night, I attended the 100th-anniversary gala at the Patronato, in a more upscale Havana neighborhood, and networked with a few professional members of the Jewish community and Jewish-Americans from humanitarian aid organizations.

I spent my last cash in Cuba on their extortionist $20 exit fee (without paying that and showing the receipt at the boarding gate, you can’t leave) and a cheap $5 Cuban cigar to prove I was there, even though I don’t smoke. When I landed in Miami, the customs official didn’t care about the cigar, but he did interrogate me about “what I was doing in Cuba.” I told him I was a journalist on assignment, and he said: “Show me your letter.”

I only thought I had to show it on arrival in Havana, but thank G-d, I had saved it and even had it handy in an outer flap of my carry-on bag.

“Okay, you’re good to go,” he said.

Well, not so fast. Arriving later that night at JFK Airport for my return trip to Israel, I went to El Al check-in, and the place was deserted. Unbeknownst to me, being offline for three days, workers at Ben Gurion Airport declared a wildcat strike and my flight had been canceled.

I had to spend the night at an airport hotel that offered me a frozen kosher meal. They said they couldn’t warm it up because the mashgiach wasn’t there. Sticklers for the rules, they wouldn’t accept my assurance that I could act as my own mashgiach, so I dug into a meal of iced chicken at midnight.

The strike ended overnight, and El Al arranged a makeup flight. I landed in Israel a day late, with empty pockets and a spoiled stomach, but the assignment produced a memorable article and turned me into a much wiser traveler.

—Binyamin Rose

Power of the Press

When the phone rang after 2 a.m. one night over ten years ago, images of possible emergencies flashed through my sleep-clogged brain. But nothing could have prepared me for the frantic voice on the other end of the line. “Mrs. Shaingarten, you have to stop them, this is pikuach nefesh, and if you don’t listen to me now, I will be a ruined man on your conscience!”

It took me a couple of moments to calm the person down and ask him to identify himself. It was a well-known person I had dealt with several years earlier, when he was involved in a Mishpacha project. This normally calm, composed, and courteous gentleman tried to explain through his agitation that he was the mistaken target of a false accusation that was about to become public knowledge. As he was gearing up for the fight of his life to clear his name, it had come to his attention that a certain piece of information indirectly related to the situation was going to be printed in Mishpacha the following day, potentially complicating his already disastrous position. He implored me to do everything possible to ensure that this seemingly innocuous information be omitted from publication.

Of course we removed any potentially damaging content from the magazine — the last thing we’d want is for Mishpacha to cause anyone damage — but I was shaken by the call for weeks thereafter, replaying in my mind how this respectable public figure had been reduced to a frantic mess.

—Nomee Shaingarten

Out of Time

Every week, we arrange for several truck shipments to bring the magazines directly from the printer to the warehouse, from where they will be distributed.

One week, the shipment didn’t arrive, and we were extremely confused since it had left on time. We called the trucking company, but it was after hours, so we couldn’t get anyone on the phone.

After doing literally everything possible to get someone to talk to, we learned that the driver had already driven most of that day for another delivery, not ours, and legally, he is limited to a maximum amount of driving hours. The clock ran out when he was an hour from the warehouse, so he turned around and drove four hours home with a truck full of magazines!

—Michal Frischman, Chief of Staff

Final Respects

One of the hardest issues to produce was the magazine covering the Meron tragedy. Every decision carried so much emotional weight. Since we ourselves were still immersed in shock and grief, it was hard to find our rational capacities and deal with mundanities like word counts, titles, and font sizes. At times like these, you daven very hard that Hashem will guide your decisions, because you realize just how small you are.

One piece came in very close to our print deadline. It shared the experiences of the precious Hatzalah and ZAKA volunteers who faced so much horror with courage and sensitivity. The writer had done an admirable job conveying their devotion while using the most careful phrasing. But as I replayed my mental reel of all those faces, thinking of sons, brothers, and husbands, I realized the piece needed one more round of edits. I went through it again, and every time I saw the word “body,” I changed it to “person.” Then I took a deep breath and approved it for print.

—Shoshana Friedman

Hong Kong Adventure

About ten days before Rosh Hashanah of 2009, I got a call from my editor at Mishpacha. They were sending reporters around the world to write about rabbanim of various kehillos. Would I like to go to Hong Kong… in three days?

“Sure,” I said. But after I hung up the phone, I wondered how I was going to go to Hong Kong, transcribe my interview notes, and write the article before the deadline, which was something like two days after I got back to Jerusalem. As I stared at my previously trusty cassette-operated pocket tape recorder, which was sitting next to the blank screen of my desktop computer, I knew it was time to update my tools of the trade. But the journey from the previous millennium to the present one was far from smooth.

Here are some of the highlights: I buy my first laptop at BUG, Jerusalem. It has English and Hebrew capabilities. Wow! Wow turns to “ow” when, during an interview in Hong Kong, I inadvertently change from the English keyboard to the Hebrew one — and I don’t know how to change back to English.

Fortunately, I also had my MP3 player with me and was recording the interview. Being paranoid about technology, my modus operandi was to record 20-minute segments, save, and then start a new recording. It worked fine in Hong Kong until the very last interview, which took place on Motzaei Shabbos, a little before the Selichos prayers began. The trip had been great fun, but by this time I was pretty tired and I had to get up early the next day to catch my flight back to Israel. So I decided I’d skip typing on the laptop and just record the interview. About halfway through the interview, when I realized I hadn’t saved the file in a long time, I glanced down at my MP3 player.

Interviewee: Is something wrong?

Me: Oh, no. What was that last bit you were saying?

Also Me: Help! I forgot to hit “record”! I have no record of anything he said!!!

Needless to say, after Selichos I spent much of the rest of the night frantically typing up what I remembered of the interview, before I totally forgot what he had talked about.

I can also mention my adventure when I had to learn how to send a text message. I had to learn this for the “honor” of Mishpacha. Because there wasn’t time beforehand to set up all the interviews, my main contact person in Hong Kong suggested:

Contact Person: When you’re here, we can communicate by text.

Me: Great!

Also Me: Help! I don’t know how to text! Where’s the space bar on this phone??? I can’t send this guy a message with run-on sentences! He’ll think Mishpacha writers are illiterate!

Fortunately, on the flight from Tel Aviv to Hong Kong, the very kind young man sitting next to me worked in hi-tech, and he patiently explained to me how to write and send a text message on my old-fashioned Nokia phone — without laughing.

And finally, there are the photographs. Back then the hottest thing on the market was a digital camera, where you took a photo, saved it to a memory card, took the card to a photo shop where they transferred the photos to a CD (photo attached), took the CD home to your computer, and… Voilà! “Instant” photos.

I first bought a digital camera in 2007, when I went to Catalonia, Spain, to do research for my novel Terra Incognita, which was serialized in Mishpacha in 2008. As I’m not a professional photographer, my ratio of blurry photos to usable ones is about 50:1, so that digital camera was an amazing help. I’d take the CD back to my hotel room, look at the photos, realize they were all a disaster, and go back with my camera and try again.

Today I’ve basically retired from magazine writing to concentrate on writing my Jewish Regency Mystery Series, and I don’t travel so much. When I do have to interview someone living abroad, it’s usually via Zoom. When Mishpacha celebrates its 30th anniversary, that will very likely be a thing of the past, too. Probably my AI persona will interview yours, write the article, and laugh about the old days when tech-challenged humans struggled with simple things like computers and digital technology.

—Libi Astaire

Our North Star

Sunday is closing day for Family First: the day when the planning, writing, editing, proofing, revising, re-editing, designing, and re-proofing comes together in a grand finale.

One Sunday, I got to the office early, feeling good. Every last piece was finalized, my letter ready — it should be an easy, quick closing. I opened my email, and the first one I saw was from the head of the rabbinic board. It was marked urgent.

I took a deep breath. This can’t be good, I thought as I clicked open the email.

It wasn’t.

Our cover story that week dealt with a delicate but crucial topic. It was written after extended discussion and guidance, and went through several iterations upon the advice of our rabbinic board. After we got the final approval, we built a magnificent cover and structured the rest of the content to complement it.

But upon reviewing the final document, the rav had had fresh misgivings — and consulted with his own daas Torah. The psak was unequivocal: The article needed to be pulled.

I rapidly cycled through the five stages of grief. Denial, then bargaining — surely was can salvage this — then anger, depression, and finally acceptance. This is happening. What now?

The magazine has seasons of plenty and seasons of famine; times when we’re way ahead of ourselves and have several features just waiting to be slotted in, and times when we work hand-to-mouth with features sliding into our inboxes dangerously later.

At that point in time, the famine was acute. There wasn’t a single feature remotely ready. Not to mention that fact that many of my writers were fast asleep, in a time zone seven hours behind mine.

Finally, I found a mini-feature that had been submitted early. It didn’t work with anything else in the issue — the topic overlapped with the Lifetakes piece, and the tone wasn’t strong enough to provide the weight we needed. But it was our only option.

We had a few essays ready for print. I’d replace the Lifetakes and add a Musings. We’d feature the recipes on the cover.

For the next few hours, the entire staff worked feverishly preparing three new pieces plus a new cover. My gut contorted with stress. We closed over an hour late, and I got home nearly two hours later than usual.

Yet thrumming beneath the surface of all the churning overwhelm, was another voice. Faint at first, then gaining volume.

It was pride.

Pride at working for a publication that placed values above all else. That insisted on being true to Torah principals no matter how inconvenient or challenging it may be in the moment. At being led by a North star that had nothing to do with a journalistic scoop and everything to do with the convictions that mattered most.

—Bassi Gruen

When the Family Grows

One of the most significant challenges I faced was managing the constant changes in manpower, particularly due to maternity leave. When I first assumed a managerial position at the magazine, the frequent turnover caused by maternity leave initially seemed daunting. However, over time, I came to realize that it was actually a positive aspect of our workplace. Maternity leave allowed individuals to return refreshed, while providing opportunities for growth and development within our team. We even welcomed some excellent long-term hires as a result of these opportunities.

—Hila Aftergut

Past the Finish

Our magazine usually goes to print on Monday night, but we delayed printing to include the results of the 2020 presidential election. We had two options just about ready to go: one for a Trump win, the other for a Biden win. The plan was for our team to beginning working at 7 a.m. — midnight in the USA — and fill in the details of the actual results so we could finalize the right option for print.

That night I couldn’t sleep because I kept waking up to check whether there was a winner. I was so restless that I decided to prepare “alfajores” (a classic Argentinean pastry) to share with the staff.

We arrived ready and raring to go — but there was no clear winner. Everyone kept refreshing their screens, checking results, to no avail. After lots of debate and discussion, we held a conference call with our US team and came up with a new package: “Fighting Past the Finish.” Baruch Hashem, we squeaked to our extended deadline, and by midmorning I was heading back home, wrapping up my workday, while others were arriving to begin theirs, saying, “Good morning!”

—Chava Lipscyz

Birds of a Feather

MY fellow halachic adventurer Ari Greenspan and I wrote in Mishpacha about the “mesorah dinner” we held, featuring exotic dishes with fascinating kashrus backstories. But our interest in this topic was ignited early on — long before Mishpacha existed!

Ari G. and I were 18 and learning in yeshivah when we first discussed the pheasant. A Yemenite bochur who was walking by and overheard us opened the door to an incredible discovery and experience.

The pheasant is listed as kosher in the Talmud, but since few communities have maintained a mesorah when it comes to this particular wild bird, it is unclear if the modern pheasant is in fact kosher. Rav Moshe Feinstein writes in a responsum in Igros Moshe that he doesn’t know anyone who has a mesorah regarding it, and so it cannot be eaten.

“Are you guys discussing the pheasant? I know someone who has seen it being slaughtered and eaten by great rabbanim. You should go and talk to Rav Kapach,” the Yemenite bochur urged.

A dayan of the beis din in Yerushalayim, leader of Yemenite Jewry, Rav Yosef Kapach was sitting in his home on a low bench poring over handwritten manuscripts. We told the Rav we had learned shechitah, and he showed us the horn of an ibex that he had shechted. The Rav’s opinion based on his mesorah was that pheasant could be shechted and eaten.

A few weeks later, after inquiring at the Jerusalem Zoo, and encountering a bird keeper near Tel Aviv, we took a bus to a kibbutz in the north where we bought two of these royal birds. The roads up north were empty of civilian traffic. We naive Americans saw the army jeeps and trucks and didn’t quite understand what was going on — actually, it was just two days before the outbreak of the first Lebanese war.

Rav Kapach was excited when we brought the pheasant in. He shechted one, then looked on while I performed shechitah on the other. Then he sat down and wrote a letter identifying the bird in several languages and explaining that he had seen the pheasant slaughtered and eaten by rabbis in Yemen and had passed on the mesorah to Ari Greenspan and Ari Zivotofsky.

One of the greatest regrets of my life is that we didn’t get the opportunity to discuss this topic with Rav Moshe Feinstein in person. We wrote a letter and were answered by a secretary, but Rav Moshe became ill and passed away shortly afterward.

—Ari Zivotofsky

The Chosen One

I’ve been to a lot of interesting and sometimes even scary places over the years, but rarely was I shaken up as acutely as the time I got into the elevator at Herzog Hospital and pressed minus-five: Down, down, down underground, into the hospital’s closed psych ward. I was there to interview Professor Pesach Lichtenberg, the hospital’s director of men’s psychiatry and a world expert on “Jerusalem Syndrome” – a kind of religious psychosis where people become so overwhelmed with the spiritual symbols of the Holy City that they believe themselves to be biblical figures or hand-picked emissaries for a Divine redemptive mission.

It could be the man in the Israelite tunic with the flowing beard holding up a placard warning of the looming Armageddon, the Christian tourist walking around the Old City wrapped toga-style in his hotel’s bed sheet, or the young chassid hanging around one of the gates to the Temple Mount waiting for instructions he believes he’s received from Above.

When I arranged the interview, I wasn’t looking to find a candidate for Mashiach, but it was pretty clear from the screaming coming from behind the barricaded doors that there were a few of them on the ward.

One patient was hollering, “I’m the Mashiach!” and from another room came the rejoinder, “That’s great, just don’t say it so loud or you’ll get another injection!”

I wanted to hear about the fine line that separates someone who has had an authentic religious experience from one who has lost his grip on reality – how one person is considered a praiseworthy and true ma’amin, waiting daily for Mashiach to arrive, and another is considered over the edge because he thinks he’s been appointed as part of the process.

Professor Lichtenberg said he always lets his patients unspool their stories no matter how zany they sound. “Every believing Jew hopes daily for Mashiach,” he told me, “and I’ll admit that there have been a number of people I’ve met in who have managed to arouse a certain hope that, hey, maybe this is the real one!”

He said it as a joke, yet when I walk through the Old City, I’m still sort of looking for those shofar-blowing Mashiach-wannabes who might wind up in Herzog. But I’ll still be wondering: Maybe this is the fellow we’ve been waiting for all these years?

—Rachel Ginsberg

Real People, Real Lives

Last Pesach, I helped coordinate a collection titled, “On the Shelf,” in which writers shared the backstory of a prized possession they will forever keep.

One of the stories, prepared for print by Rivka Streicher, described the Cabbage Patch doll of a young woman named Zahava who had grown up in Israel. Zahava had struggled in childhood, her mother explained, and as a teen, she left home to attend school in the United States.

Then Zahava was diagnosed with cancer, and when this story was submitted for our “On the Shelf” collection four years later, she was still fighting the dreaded disease.

“Some days there are glimmers of hope, but most are awash with despair, and I still occasionally find comfort in my old friend on the shelf. I look at her with tearstained eyes, and she holds my gaze, serene as ever,” Zahava’s mother concluded the piece. “Perhaps this is her new role: to teach me acceptance, bitachon, emunah. I will not throw out Zahava’s Cabbage Patch doll, I will not give her away. She is still reserved for a miracle.”

It was a heart-wrenching piece, inspiring in its raw description and pained acceptance.

Wednesday night, I finalized the text, and Thursday morning, I emailed it to our production department to prepare for print early the following week.

Thursday night, I received an email with those three dreaded words: Baruch Dayan Ha’Emes.

To say I was shaken is an understatement. Zahava’s story had been my story for the last few weeks, and as her mother and stepfather recounted the doll’s saga, they had been sharing her progress (not good) and her ups (not many) and downs (too many). I knew when she experienced a downturn, when she was back in the hospital, and when her mother flew to America to be at her side.

Zahava’s stepfather helped us end the piece with this carefully worded text, approved by the bereaved family: “Shortly before this issue went to print, Zahava’s soul returned to her Maker. Her doll still sits on the shelf and waits until Mashiach’s arrival. Yehi zichrah baruch.”

Our ghostwriter Rivky’s response really resonated.

“I was thinking that I sit here in my home writing about people’s lives, and sometimes it’s just words on a paper,” she wrote. “But when your email came, it really drove home the point that we’re writing about real people, real lives.”

I called Zahava’s mother to be menachem avel a couple days later, and that was all I could think about. Real people, real lives.

—Rachel Bachrach

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.