Raise the Bar

| April 16, 2024A significant percentage of the factory’s output is kosher l’mehadrin, known to chocolate lovers in the frum world as Schmerling’s

T

he Swiss are famous for their watches, their Alps, and their chocolate. We took a short train ride from Zurich Airport toward eastern Switzerland to check out the latter.

A local bus brings us into Flawil, in the canton of St. Gallen. Industry hums solidly in the background of this quiet rural village. As we make the climb up picturesque country roads, it seems like an unlikely starting point to check out a staple of the Pesach shopping list.

We’re here to see Flawil’s number-one tourist attraction: Maestrani’s Chocolarium. While Maestrani is one of Switzerland’s elite chocolate producers, owners of the iconic “Minor” and “Munz” ranges, a significant percentage of the factory’s output is actually kosher l’mehadrin, known to chocolate lovers in the frum world as Schmerling’s. Need we say more?

Signs pointing to the Chocolarium building proclaim “50 Meter bis zum Glück [50 meters to bliss].” The “Chocolate Is Happiness” theme is evident all over, with swirling colors, striped poles, and fun posters in a lobby reminiscent of a magically themed children’s attraction. It’s a quiet day here, just one large group of schoolchildren enjoying the chocolate tour and eating their packed lunches, which means we’ll have some private time with the two product managers who have graciously welcomed us.

We sit down with Fabienne and Jonas, who are happy to share some chocolate history and speak about their kosher products — mentioning that Schmerling is the production line that makes it across the Atlantic to the US.

My eye is drawn like a magnet to the familiar kosher bars on sale among the other factory products (a real novelty to find mehadrin products in a little Swiss village), and in fact, every one of those fresh-off-the-line Rosemarie bars are now strictly kosher — so you no longer have to look for the packages with the special hechsher.

This quaint, rural Swiss village is an unlikely starting point for the kosher consumer’s beloved chocolate

The Brands We Love

S

ince the 1950s, kosher Swiss chocolate has become a culture of its own. Although there are plenty of alternatives today, Mendy Schmerling, the company’s third-generation CEO, says his grandfather Boruch Schmerling was the first to make Swiss chocolate kosher.

In 1903, Mendy’s great-grandfather Levi Yitzchok Schmerling was a young Russian Lubavitcher chassid employed by a German company. At a time when paranoid Russian authorities suspected anyone employed by companies outside of Russia of being a foreign agent, he didn’t feel safe. When he asked advice from Rav Shalom Dov Ber (the Rashab), the fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe told him to leave the country, and he relocated to Zurich, Switzerland.

Importing kosher cheeses and running a kosher grocery store (which has morphed into Le Shuk, one of two groceries serving the community until today, and still managed by Mendy’s mother, Mrs. Chani Schmerling) were Levi Yitzchok’s business. In 1940, when there was some fear of Germany invading Switzerland, he obtained visas to the United States for himself and three daughters. His son Boruch could not leave Switzerland, as he was of military draft age, so he remained behind with his mother. In 1946, Levi Yitzchok passed away in New York, and Baruch would continue his kosher food business in Switzerland with the blessings of Rav Yosef Yitzchok Shneerson, the Rebbe Rayatz.

Boruch established a connection with the owners of Maestrani, a chocolate factory founded a century before by an Italian chocolate manufacturing pioneer named Aquilino Maestrani, who first began chocolate production in Lucerne, and moved his factory to St. Gallen in 1959. It was in the 1950s that Boruch Schmerling began actual production of chalav Yisrael products for the first time (remember the blue Schmerling triangles and cheese slices?). Boruch decided to approach the Maestrani factory, which had just moved to St. Gallen, to create chalav Yisrael versions of the Rosemarie and Minor, which were their main lines back then.

Since Boruch had a brother-in-law in the Unites States, he had a channel for exporting his chocolate products to the American Jewish community from the outset.

The chocolate mixture starts out crumbly, then gets pulverized into paste, and then travels as a sweet brown river into pipes and molds

Molten Magic

T

he history is interesting, but really, we can’t wait to get to the “chocolate experience.” The smell wraps itself around us as we step in: warm, fragrant, luxurious, like being in a bakery with the richest, purest chocolate cake wafting from the oven.

The process from raw cocoa bean to melt-in-your-mouth square is an open book here, with huge floor-to-ceiling viewing windows opening onto the actual factory floor. But Fabienne explains that sometimes visitors might find the machinery idle, with no rivers of molten chocolate lava flowing down to fill the molds, and no humming of the giant mixers.

“When we prepare for a kosher run,” she says, “the relevant part of the production line has to be cleaned, which takes several days, and then it sits for 25 hours before kashering. At that time, visitors will notice that the machines are still. But if you’re here on a lucky day, you’ll find the entire line in mid-production. You’ll see…”

Visitors can handle and taste raw cocoa beans brought from Peru and processed on site; get the feel of milking a cow; and learn how cocoa butter, cocoa solids, and cocoa liquor are produced. We learn that milk chocolate was invented in Switzerland in 1875 — talk about an inspired shidduch — and that Maestrani used milk from the local Swiss cows (with the bells around their necks, of course.)

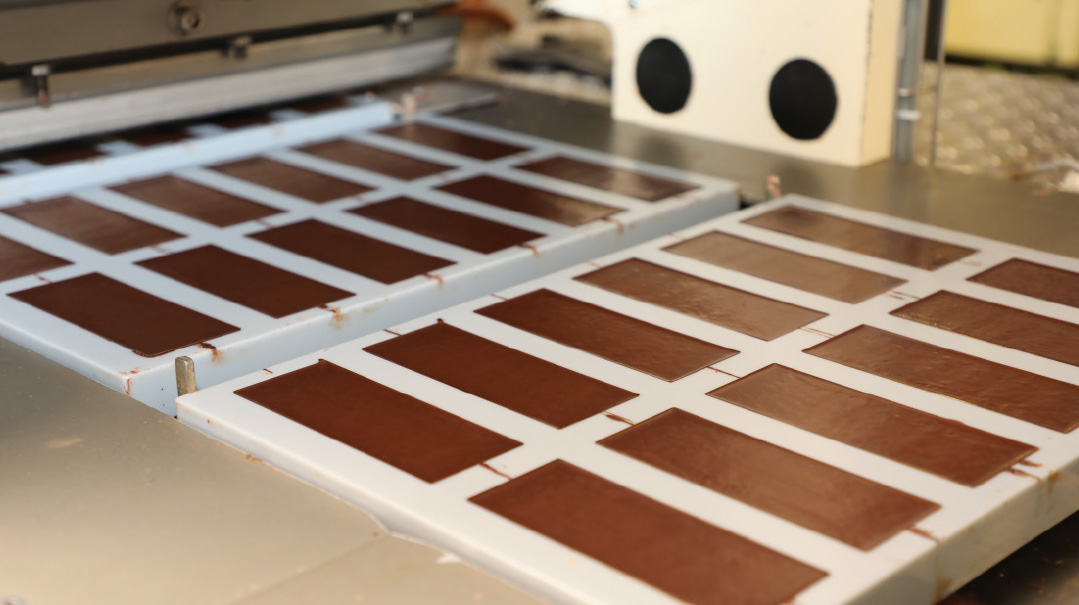

The chocolate mixture starts off crumbly, sandy, but we can see it being transported upward, where it will be pulverized inside a great roller, into a paste.

Then it comes down a floor, for conching — a kind of prolonged kneading. Like the quantities of ingredients, the length and temperature of the conching process are different for each product and are great state secrets. Conching unifies the ingredients and smooths the chocolate into velvety bliss, but there is a difference in the smoothness of the bite between each product.

Some bars have that creamy, dreamy texture with flecks of nut, others are built on praline paste or coconut paste, with whole, salted, or caramelized nuts. There is dark chocolate, milk chocolate, and white chocolate (always processed in that order to avoid flavor transfer), fine chocolate for adults and fun chocolate for kids, including chocolate ladybugs and mini bars.

I ask if there have been any bloopers, like the batch that accidentally mixed up the mint flavoring with the praline paste, but apparently, we’re in the wrong place for such mistakes. Swiss precision simply won’t allow it.

“The ingredients are added manually, and there is quality control at each and every step of the process,” Fabienne says. “There are technical checkpoints and clear processes for staff, so it really can’t go wrong.”

Pink lights swirl in a chocolate sensory room. Fountains of dark, milk, and white chocolate greet us, and we’re offered plastic tasting spoons, but since this part of the experience has no kosher certification, they know we won’t touch it.

The mutual respect, says Mendy Schmerling, means the company is willing to upgrade the kashrus standards in accordance with industry innovations

Time for a Change

ON

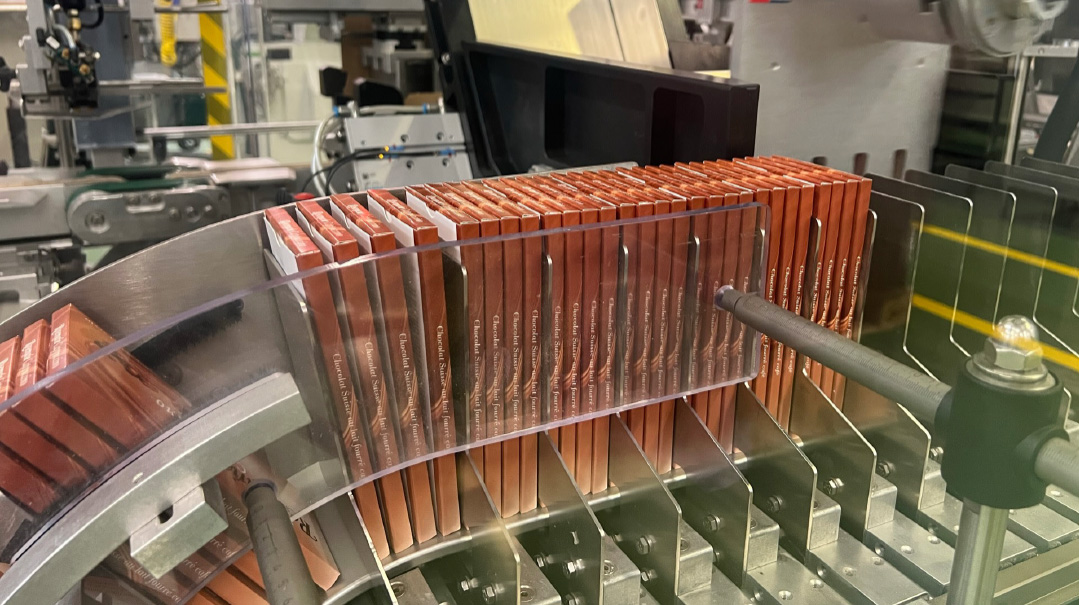

to the next level of the factory. I can’t believe that my favorite bar is on the lines today: Rosemarie Cappuccino! Machines carry yellow placards with the word “Koscher,” and this is a bona fide supervised run.

The liquid chocolate mass runs through pipes that cool it. Then, once it’s tempered, it’s poured into forms, filled, and popped out of molds. It’s fast yet precise. I watch freshly produced cappuccino bars speeding on conveyor belts like mini cars on a highway. They then get wrapped in foil, whizzing toward the machine that envelops them in a coffee-colored card. Then they fill up the brown cartons that are used to protect the exported products as they make their way across the world.

Jonas runs down to the factory floor and reappears two minutes later with a handful of bars, so new they’re still warm. Nothing bought in the grocery can compare to this melt-in-your mouth chocolate freshness.

Since boiling water and high-quality chocolate don’t mix well — water can damage the chocolate and the machinery — for decades, the only way to kasher a chocolate factory was by heating cocoa butter up to high temperatures and using it in liquid form to kasher parts of the machinery.

Some years ago, a breakthrough rippled through the industry when it was discovered that with certain technical changes, it was possible to kasher a chocolate factory with water. Once this was established, some hechsherim ruled that the formerly accepted standard of koshering with cocoa butter was no longer acceptable, since cocoa butter is only liquid at certain high temperatures and becomes solid as soon as it cools. The American hechsherim ruled this way, while the kashrus leaders in Eretz Yisrael and Europe thought otherwise.

Mendy Schmerling felt caught between the way things had always been, the likelihood that the factory management would balk at using boiling water on their machinery, and the need to keep up with kashrus innovations and improvement, especially for his American customer base. How could he explain to the factory owners that the kosher procedures they’d always followed needed to be upgraded?

Meanwhile, Maestrani announced that after 70 years, it was planning a move from the city of St. Gallen to Flawil.

“Since they were building a new factory, we sat down with the engineers and with the certifying rav, and were able to build into the new design the technical modifications that allow us to kasher on the new, higher standard,” says Mendy, who still marvels at the Hashgachah pratis that helped him offer improved kashrus standards in the nick of time.

The change was a major event that involved retraining the factory staff.

“We didn’t want to just give them orders,” Mendy explains. “We held information events and invited everyone in the factory to hear. The rav explained the kashrus concepts and the reasoning, which absolutely boggled people’s minds. The fact that the laws have been the same for 3,000 years and we’re still applying those principles today — how materials absorb flavor, or the difference between porous and nonporous materials, for example — was fascinating for them.”

The mutual respect and understanding helps things run smoothly. The rav who supervises the production receives the highest respect from the employees. Once, when he identified an issue that necessitated pausing the kosher production, with the machines having to sit unused for a few days and then be kashered, the management and staff understood that there could be no compromise. They absorbed the heavy financial loss of the manufacturing time, as well as a few tons of chocolate. (Yes, it could be melted down and reused in a nonkosher product, but that still entails a loss).

A rabbi from another kashrus authority once visited the Maestrani facilities. “I’ve traveled all over the world for kashrus,” he said, “and you don’t see factories as clean as Swiss factories anywhere else.”

Truth is, in Mendy’s view, the kosher-run actually makes life a bit more interesting for factory employees. “It’s a bit of a change from the same-old day to day. I think it offers them something of an enjoyable challenge.”

What Sells Best

M

endy Schmerling, who’s based in New York, tells me he’s also a lover of the Cappuccino bar. “It’s my second favorite. The great thing about it is it uses real coffee — but it won’t keep you up. You get your coffee with only a minute amount of caffeine.”

And his favorite?

That would be the Caramel Sea Salt bar. That one is a witness to shifting tastes. When it came out, Mendy recalls, the flavor profile was already popular in many American products. But Israeli customers wondered what salt was doing in their chocolate bar. Now, it’s already taken hold and become popular across the market.

In the world of nonkosher chocolate, companies alter their recipes to cater to different tastebuds in different locales. Americans like their chocolate sweeter than Europeans do, so Cadbury adjusts the taste of their products in different production sites. But kosher consumers are used to buying imported kosher products, so Schmerling’s recipes are the same wherever you buy them.

Different locales do have their idiosyncrasies, though. Sometimes, the wrapping takes on a life of its own. When Schmerling redesigned their wrappers, their Israeli distributor advised them not to change the wrapper of the Israeli best-seller, the Rosemarie Milk bar. Mendy’s team had been planning to replace the brown-and-green label with a new blue hue, but they kept the old wrapping too, and labeled that bar “Rosemarie Nostalgia.”

Today, the brown-and-green Nostalgia bar sells right next to the blue Rosemarie Milk bar all over Eretz Yisrael. The chocolate inside is exactly the same, but the Nostalgia bar outsells the Milk by a factor of ten. The pull of the wrapper is so great that Nostalgia is Schmerling’s number-one selling chocolate across the board. In America, its equivalent, Rosemarie Milk, is the most popular. The number-two spot is occupied by Rosemarie Harmony, which Mendy says was a surprising high achiever, given that the team was not totally confident that it would float up to the sales ceiling.

There have been failures, of course, and Mendy is not shy about mentioning them. “The vegan almond bar that came out two years ago didn’t go well at all. Apparently, the word ‘vegan’ scares the kosher consumer.”

The vegan bar had been developed and was ready to go for a while, when Trader Joe’s came out with a vegan chocolate with a pareve hechsher. Jewish influencers touted the new product, which sent people running out to buy it. (Since it was pareve, with no chalav Yisrael issues, kashrus was an easier issue.)

To Mendy Schmerling, this signaled that the kosher market was ready for his vegan bar too, which was not your typical dark pareve chocolate, but a unique bar with a creamy, almost milky taste, created by using almond butter. What could be better for people who are fleishig, as well as the lactose intolerant population? But the “vegan” marketing might have been a mistake, as it seems to have distanced customers — the bar performed poorly, and it’s been discontinued for now.

Mendy’s father, Levi Yitzchok Schmerling a”h, together with Rabbi Berel Lazar upon his arrival to Moscow; and loading a truck of food for Jews in Russia in the early 1990s. Swiss neutrality made it easier to send the shipments

Staying Relevant

M

endy keeps up with what’s getting melted and molded by chocolatiers worldwide by attending multiple trade shows. Yet he knows that the kosher market moves more slowly than its nonkosher counterpart, and he’s looking for real trends, not fads.

“When I see that something is growing and growing steadily, we think about working toward it in chocolate,” he says.

While we’re speaking, UPS has just brought a case of the newest flavor up to Mendy’s New York office, straight from Flawil. It was produced in the factory just two days ago, a bar of milk chocolate with sea-salted almonds. He unwraps a bar gently.

“We went through seven or eight variations of this, even though it’s a simple bar,” he explains. “The amount of salt had to be just right. Too much salt would overpower the chocolate flavor, and every time we tweaked the salt, it affected the ratios of the rest of the ingredients.”

I’m imagining that Research and Development must be a tasty job. Although the team members at the factory are trained in food technology, Mendy will also use the discriminating taste buds of his kids to hit the sweet spot. After all, chocolate is in their blood.

It’s apparently a serious and scientific process to develop a new chocolate bar, and the collaboration from New York to Switzerland is ongoing, although mostly remote. With Mendy flying in a few times a year, they view him as a partner, and when his Schmerling team comes up with ideas for new products, the Maestrani Research and Development team sources the required kosher ingredients and makes up some samples — every single item checked by Schmerling’s rav hamachshir, Rav Chaim Moshe Levy of Kehal Adass Yeshurun in Zurich. After tasting, samples are reformulated. Design and packaging can be a lengthy process, too.

“Each tweak can take a few weeks,” Mendy says, “so it can be a year from conception to release of a new product.”

To source ingredients that are high enough quality for this perfectionist brand, also kosher l’mehadrin and kosher l’Pesach (all Schmerling products are kosher l’Pesach, besides the sugar-free lines), can test the team’s tenacity and commitment to the limit. The most challenging product to manufacture, Mendy tells us, is the Rosemarie Kids bar, because its filling requires clarified butter.

“We used to produce it ourselves, but can’t anymore. We now have to source high-quality kosher butter and clarify it in a separate specialized facility. It’s very challenging to locate this butter — at the moment we have a source for it in England,” he says. “What don’t we do for the kids?”

I commiserate, while at the same time wondering if kids really mind eating adult chocolate bars.

After 70 years, the relationship between Schmerling and Maestrani is solid and loyal. Mendy remembers the old team members who worked with his father and grandfather, but of course employees change, and today there are 160 Maestrani employees, of 15 different nationalities.

“We always had good relationships,” he says. “St. Gallen has a proud history of saving Jews during World War II. Mrs. Recha Sternbuch was based there, and the police commander of the canton, Paul Gruninger, disobeyed Swiss law to help hundreds of Jews escape from Austria to Switzerland. The people are still proud of what they did for the Jews.”

Mendy looks back at a history that combines kashrus with chesed. In the 1980s, when Gorbachev’s glasnost policy made thin cracks in the Iron Curtain, his father got involved in sending kosher food to Russian Jewry via the emerging network of Chabad shluchim posted there.

“He had the know-how about product shipments, so he put together containers from all over Europe — chocolate and cheese, but also so much more,” Mendy relates. “He worked with the Ezras Achim organization. Swiss neutrality made it easier to send the shipments, and he soon grew bolder and included seforim and tefillin, too.”

He still meets Jews from the former USSR who remember the precious kosher food items from Switzerland. Those who were committed to keeping kosher faced severe shortages, and the Schmerling shipments made a difference.

Off the Shelves

W

hat about the bars you find squirreled away on a top shelf in your Pesach kitchen from last year, now past their expiration date?

“Chocolate is not wine. It doesn’t get better with time,” Mendy says. But then he qualifies. “Well, it depends how it’s been stored. If the temperature is consistent, nothing will happen to it. It won’t become dangerous. It might have cosmetic damage, the fat pushing up to the surface, or it might taste stale.”

Still, once the product is out of his temperature-controlled warehouses, temperatures fluctuate every day. And bars with nuts, he says, should never be eaten after the expiration date. They’ll taste off, and the nuts can become rancid.

Recently, Mendy got a picture of a tribal member in Zimbabwe holding a Rosemarie bar, delivered by someone from Israel. The guy looks happy, but nowhere near as content as the family taking their first Schmerling bite after turning over their kitchen.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1008)

Oops! We could not locate your form.