The Angels who Battled Compromise

The Malachim were far more than a Chassidus; they were the malachim, the angels sent from on High to prepare this country for a brilliant future.

The “Malachim” of Williamsburg

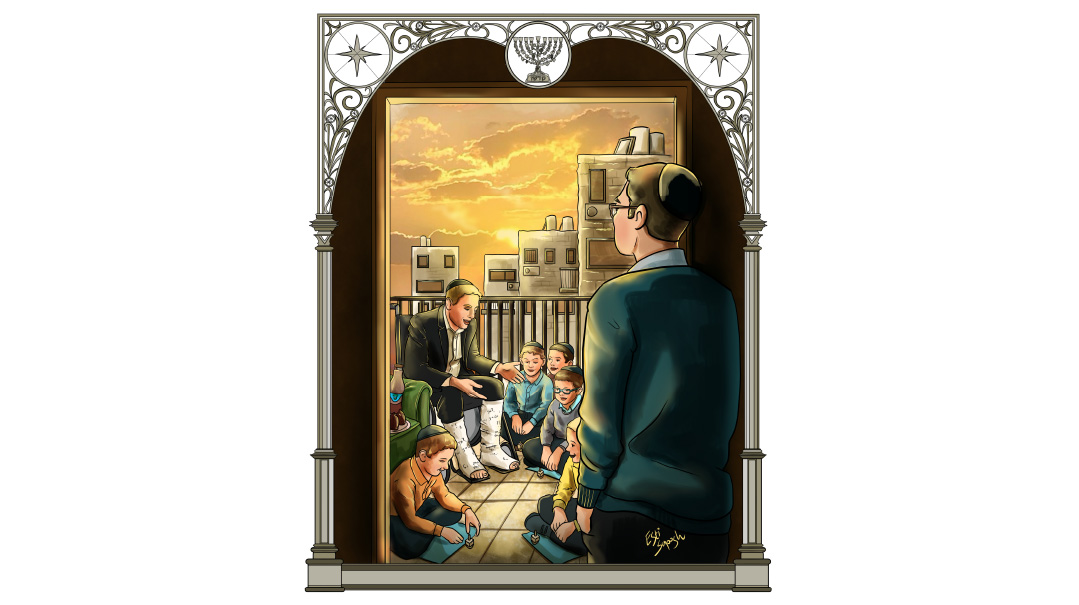

“Don’t rock the boat!” they were told. “Don’t make a scene!” they were warned. But despite the antagonism, a small group of determined young Jews continued to circle about pre-war Williamsburg with flowing beards, long coats, and endless veneration for their leader, Rav Chaim Avraham Dov Ber HaKohein Levine, whom they termed “the Malach.” Yisroel Besser paints a riveting portrait of the fearless Malachim and their battle against compromise

For Reb Ben Zion Weberman, it was a defining moment in his life. Right here, on the impure soil of the new world, he had found a figure so intense, so forceful and strong, as to make him believe that it was possible. There was a hope that his children, and their children as well, might grow up like Yidden had for hundreds of years in Europe, that the values and norms of the Old World might have a home here as well.

Reb Ben Zion was an anomaly: a lawyer by training and profession, he was one of the founders of Yeshivah Torah Vodaath, yet he yearned for the shtetl. Even as he watched a generation of clean-cut American yeshivah boys take root here, in America, he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted more; more of a barrier between the boys and the American youth. He wanted them to be as different from their secular compatriots as angels are from men.

It was his father, Reb Moshe Weberman, who discovered the saintly European Rav with the angelic countenance. On a summer visit to Kantrowitz’s hotel in upstate New York, Reb Moshe first beheld Rav Chaim Avraham Dov Ber HaKohein Levine, or “The Malach.”

The Malach had been the Rav of the small White Russian town of Ilya, and his ascetic, otherworldly ways had earned him the title of “The Malach,” the angel.

He combined the penetrating intellect of Brisk with the emotional depth of Chabad. Armed with these gifts, did he arrive here in America, where he led a small shul in the Bronx, Nusach HoAri. Reb Moshe Weberman hurried to tell his son, Ben Zion, of this discovery.

Reb Yidel Weberman, son of Reb Ben Zion, is one of the few people alive who truly remembers The Malach. He was raised as a chassid of the Malach, or “‘The Rav” as he calls him and it is clear from speaking with him that even today, over seventy years after The Malach’s passing, Reb Yidel is still very much his devoted chassid.

He exudes a certain chiyus, a vitality, common to “mesirus nefesh” Yidden, to people who have endured suffering for His name and glory. There is something about him, this old warrior, which tells of long-ago battles waged and won, a quiet sense of triumph.

This is strange, for Reb Yidel grew up in comfortable America, in the land of the free, far away from the bombs and gunsmoke of Europe. There were no wars here.

It was Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, the legendary founder of Torah Vodaath, who sent the first boys to meet the tzaddik. Reb Shraga Feivel was always on the lookout for gutte Yidden, for real Jews to whom he could expose his boys.

The boys, that first group, were captivated by The Malach. His message became their message; his attitude, their attitude. And his enemy, which was called compromise, became their enemy as well.

He infused them with his derision and contempt for the American street, endowing them with an appreciation for their sacred legacy; they were no Americans, they were Yidden.

They began to sprout beards and let their peyos flow free. They wore large pairs of tzitzis, strings blowing proudly in the wind as they walked in the street. They were visibly, conspicuously, cheerfully different.

Organized American Jewry did not look kindly on these boys, these youngsters intent on shattering the perceptions of the secular and non-Jewish majority. “Don’t rock the boat,” they pleaded. “Don’t make such a scene,” they urged. They were self-conscious and they were embarrassed.

The term “malachim” given to these boys who gravitated to The Malach was no longer an admiring acknowledgment of his angelic conduct; it was said in mocking tones, a scathing and disdainful label for boys who, they felt, knew not how to behave like regular people; they were “malachim.”

Rav Shraga Feivel himself got involved. The tensions between this group and their contemporaries were growing. The school administration was annoyed at the steadfast refusal of the Malachim to attend secular classes or dress like everyone else.

There was no longer common ground.

The Malachim, organized a yeshivah of their own, and the first chassidic group on American soil was established.

It was The Malach himself who chose the name, first suggesting Yeshivas Maharal MePrague, then switching it to the name of one of the Maharal’s seforim, Nesivos Olam.

From the outset, there were challenges. Initially, the yeshivah had no home, and the bochurim learned in the dining room of the Shain family. The government refused to recognize an institution that taught no secular subjects, and tried repeatedly to close it down.

But they persevered, this motley crew of bochurim from Poland and Hungary, from America and Russia. The Rosh Yeshivah was Reb Yankel Schorr, one of The Malach’s older talmidim. The Malach himself visited infrequently, but the bochurim would travel to the Bronx each week to hear a chassidic discourse from him. In addition, they would often travel to their Rebbe as individuals, seeking guidance or encouragement.

He was indeed angel-like. He was a large man, physically imposing, with a flowing white beard and eyes filled with light, who measured his words, investing each one with an aura of significance. His words seared their young hearts, and apparently, they still have the ability to awaken the soul, even though decades have passed.

Reb Yidel is sharing a conversation with me that he had with his Rebbe. He remembers how while they were speaking about learning Torah, the Rav had cried out with passion and feeling, “Toras Hashem!”

Reb Yidel repeats the words and, suddenly, the floodgates of tears open. As he weeps freely, he tells me how the words, “Toras Hashem,” in the Rav’s distinctive tones, have been echoing in his ears throughout the decades, shaping his destiny.

The Malach managed to transmit an appreciation for their sacred charge at that critical juncture in history, for their particular responsibility to the future of American Jewry.

He perceived that Europe was no longer a viable option for them. In fact, one of his first chassidim, Reb Zanvel Gertner, was a bochur in Torah Vodaath in 1930. He had recently arrived from Romania, leaving his family and the only life he’d ever known behind in his native country.

He was depressed, skeptical about the opportunities for spiritual success in this country, and longing for shtetl life. He decided that he was going to return home, and a friend convinced him to visit The Malach for a parting brachah.

“Don’t go back,” cautioned The Malach. “You can become an ehrliche Yid here too; it’s dangerous there.”

“My mother writes me that all is peaceful in Romania,” the young bochur protested.

“She sees now; I see in ten years from now.”

During his last days, in 1938, The Malach would stand at the window, contemplating the heavens, mumbling sadly to himself, “What will be in Europe, vus veht zein?”

America was the land that he disdainfully referred to as omek ra, the depth of evil. Yet his vision for it was glorious, and he would comment that “America will yet have Yidden like those of a hundred years ago.” He and his bochurim would do their part to lay the foundation for those Yidden.

He never promised that it would be easy; in fact, he told them that “the Tannaim and Amoraim longed to serve Hashem in just such an era, when every bit of Torah and avodah kumt uhn shver [is so difficult], making it so much more precious.’

He told them that their beards would cleanse the atmosphere in the streets of New York, that their long coats and Yiddish conversations would create a holy new reality, would have powerful reverberations for years to come.

And so, when the remainder of European Jewry came limping onto these shores, desperate for familiar faces and language, it was these faces, the bearded faces of these American-born youngsters, which greeted them and assured them that they were welcome.

Some of the most illustrious leaders of the postwar kehillos, such as the Shopraner Rav and Rav Yonasan Shteif, found warmth and reassurance between the walls of the Nesivos Olam shtiebel.

The Malachim were far more than a Chassidus; they were the malachim, the angels sent from on High to prepare this country for a brilliant future.

The Satmar Rebbe, perhaps the figure who gained the most from their revolutionary approach to American life, appreciated it and recognized the debt that he owed them.

Reb Yidel remembers a Simchas Torah hakafos which he spent in the Satmar beis medrash, after the Rebbe had already attracted a large following. Reb Yidel was standing inconspicuously in the back and was surprised to be honored with a hakafah, a tribute to his Rebbe, the man who had made it all possible.

Reb Yidel recalls another occasion, sitting among the crowd of Monsey Yidden assembled to greet the Satmar Rebbe on his first visit to Monsey, in the 1950s.

It was the first gathering of the entire Monsey Torah community, and between the chassidim, the talmidim of Beis Medrash Elyon, and the balabatim of the Beis Yisroel shul, there was quite a large crowd on hand.

Reb Yidel heard how the revered mashgiach of Yeshivah Beis Shraga, Rav Mordechai Schwab, leaned over to the Rav of neighboring Spring Valley, Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, and asked him how Monsey had merited to evolve into a magnificent Torah community even while larger towns and cities across the state and country had never grown to such proportions.

Reb Yosef Dov smiled and replied, “If you would have seen The Malach, who spent summers here, walking up and down First Street in Spring Valley, engrossed in his holy thoughts for hours and hours, you wouldn’t have any questions!”

I ask Reb Yidel if the local American rabbanim of the 1920s appreciated the illustrious figure they had in their midst; if they would visit him.

“There were few that appreciated him here, but the visiting Lithuanian Roshei Yeshivos that would come to America to raise funds, would come to The Malach.’

“In fact, the sainted Kamenitzer Rosh Yeshivah, Reb Baruch Ber Leibowitz, came to visit the Rav in the Bronx, and there were some people who tried to discourage the Rosh Yeshivah from doing so.’

“Reb Baruch Ber was adamant about going.

“The Malach is a ‘mentsch vus hut geshushket mit mein Rebbe in Moireh [someone that carried on whispered conversations with my Rebbe in the sefer Moreh Nevuchim of the Rambam],” Reb Baruch Ber exclaimed, “and you say I shouldn’t go meet him?”

Reb Baruch Ber was referring to the study session that The Malach had with Reb Chaim Brisker, during which they studied the philosophical work. Reb Chaim would allow no one, including his closest talmidim and his sons, to listen to their interpretations.

Reb Yidel related another episode that he heard about that chavrusashaft, study partnership. Once, The Malach offered a solution to a particularly complex difficulty in the words of the Rambam and Reb Chaim, celebrated for his own ability to “split hairs” with intricate Talmudic reasoning, was astonished by the clarity and precision of the Malach’s answer.

“If you would have learned the fundamentals of Chabad Chassidus, you would have said the same thing,” commented The Malach to Reb Chaim.

Another illustrious visitor that The Malach received was Reb Elchonon Wasserman, the Rosh Yeshivah of Baranovitch. Reb Elchonon was a prime disciple of the Chofetz Chaim, who held The Malach in great esteem.

Reb Yidel shares with me something that he heard from Reb Refoel Zalman, the Malach’s son. When Reb Refoel Zalman was leaving Europe for America, he traveled to Radin to seek the blessing of the tzaddik.

“Your father can travel to America,” commented the sainted Chofetz Chaim.

A few chosen words from the holy mouth of the nation’s leader, a blessing and a directive all at once from the saintly Chofetz Chaim — he can go to America.

Another of the Chofetz Chaim’s close talmidim, Reb Yaakov Moshe Shurkin, came to visit The Malach when he arrived in America. He recalled that The Malach had often come to Radin to learn with the Rosh Yeshivah, Reb Naftali Trop; Reb Naftali would share his deep and penetrating shiurim with The Malach, who would learn Tanya with him in exchange.

Parenthetically, The Malach offered Rav Shurkin the job of Rosh Yeshivah in Nesivos Olam, but only on the condition that he grow a beard, an offer that Reb Shurkin declined to accept.

One of the richest and most intriguing relationships that The Malach enjoyed was with the Yerushalmi kabbalist, Reb Yeshaya Asher Zelig Margulies.

The two never actually met, but the collection of The Malach’s correspondence, entitled Otzar Igros Kodesh, is filled with letters to Reb Asher Zelig.

Reb Yidel tells me how it all began:

Reb Asher Zelig said a shiur in a prominent Yerushalmi institution, and relied on his salary to provide for him and his family.

One winter, the administration was several months late with his salary, and Reb Asher Zelig inquired of another employee at that yeshivah how he was managing. Reb Asher Zelig saw the other’s discomfort and realized that he was the only one not receiving his salary.

He approached the administration and they admitted that indeed, they were withholding his salary and would continue to do so unless he would tone down his inflammatory anti-Zionist rhetoric.

It was a long, hungry winter for Reb Asher Zelig and his family.

Pesach approached, and the tzaddik wondered how he would be able to provide his family with the holiday necessities. He never considered altering his views or suppressing the words that needed to be said, and he left it to Source of all Sustenance to remember him as well.

It was the day before Pesach when the envelope arrived from America, addressed to Reb Asher Zelig. He opened it to find two hundred American dollars, an enormous sum in those years, more than enough for him and his family to celebrate the Yom Tov with joy.

It was from an unknown Jew named Chaim Avraham Ber HaKohein Levine.

“I know what you are enduring for your beliefs,” wrote The Malach, sending a message of encouragement and support.

Their friendship continued for many years and Reb Yidel recalls that fateful Shavuos when the Malach’s holy soul left this world. On the second day of Yom Tov, a telegram arrived from Reb Asher Zelig in Eretz Yisrael, where it was no longer Yom Tov.

“How is the Rav?” was the urgent question.

Years later, Reb Asher Zelig told some chassidim of The Malach the contents of his dream during the night of Motzaei Shavuos. He had seen the heavenly hosts, malachim, running around in front of the Kosel, as in anticipation of a great guest. “The Kohein Gadol is coming,” they were saying to each other.

And so he knew.

The Malach allowed no pictures to be taken of him. Once, he suspected that his daughter had his passport picture and he ordered her to give it to him. He tore the picture into pieces.

Thus, there are no known pictures of him.

As I spoke with Reb Yidel, I took a chance. “Can I see a picture of The Malach?”

Reb Yidel looked at me in surprise. “The Malach didn’t like pictures.”

I try again a few minutes later. “I would love to see a picture of The Malach.”

Reb Yidel is no youngster, but after studying me for a long while, as if ascertaining the purity of my intentions, he shuffles off to his room.

When he returns, his hands are trembling. He is holding a small brass frame. “This was given to me as a gift by Reb Refoel Zalman. It’s not for printing.”

I rise and accept the small picture.

The Malach.

The picture isn’t especially clear, but I am riveted, standing there in silent contemplation.

His holy eyes are looking at an America that we will never know, seeing roads that would be traveled, bridges that would be crossed, paths that would be forged.

Perhaps he is seeing an age of professionals arriving for work in Manhattan with flowing beards and peyos, of children with their tzitzis flying high over the handlebars of their bicycles. Perhaps he is hearing the rich tones of Yiddish filling the streets of a hundred American neighborhoods. Perhaps he is seeing the gifts that he gave us.

And maybe there is a hint of a smile on his face. …

The Malach

The Malach, Reb Chaim Avraham Dov Ber HaKohein Levine was born in the White Russian town of Krisleva, where his father, Reb Shneur Zalman was the Rav. Reb Shneur Zalman was a close chassid of the “Mitteler Rebbe” of Lubavitch, Reb Dov Ber, and subsequently of his son, the Tzemach Tzedek.

When the Malach was but a child, his father passed away, and he was raised by the tzaddik Reb Zusha Kurinitzer, a close friend of his father’s.

One night Reb Zusha walked into the child’s room and moved his bed from one corner to the other. In the morning, young Avraham Ber saw how a large chunk of wood had fallen from the ceiling above where his bed had previously been, and that Reb Zusha had saved his life by moving the bed.

“I will tell my friends,” the boy told Reb Zusha.

“Avraham Ber, you must learn how to see things and still remain silent,” replied Reb Zusha. It was a lesson that the Malach would never forget.

The Rav learned the revealed parts of the Torah from a great gaon, Reb Reuven Arsislover. Once, the Malach visited the famed Kovno Rav, Reb Yitzchak Elchonon Spektor, who was impressed by the bochur and insisted that he accept a letter of smichah, telling him that it would come in helpful one day.

Eventually, he became Rav in the town of Ilya and his reputation began to spread. His hasmadah was legendary; his son related how on Friday nights, his father would remain standing at his shtender from six o’clock in the evening until six o’clock the next morning, after which he went to the mikveh and davened Shacharis. He was an intimate chassid of the Rebbes of Lubavitch, and was given the singular distinction of being allowed to study the discourses of the Mitteler Rebbe from the Rebbe’s own handwritten notes.

At one point, the Malach was hired as a private Rebbe for the future Lubavitcher Rebbe, Reb Yosef Yitzchak, but the arrangement didn’t last long.

After leaving Lubavitch, the Malach made the acquaintance of several other Rebbes, including the sons of the Sanzer Rav and the Minchas Elazar of Munkatch. He also won the admiration of the various Lithuanian Roshei Yeshivos, who were respectful of his proficiency in Shas and poskim. In particular, he was a close friend of Reb Chaim Brisker.

In 1923, after his son Reb Refoel Zalman travelled to America, the Malach followed. Upon his arrival here, he became Rav in the Nusach HoAri shul in the Bronx, where he carried on with his lofty avodah in relative seclusion.

On a visit to Woodridge, New York, the Malach was first “discovered” by Reb Moshe Weberman, the father of Reb Ben Zion Weberman. Reb Ben Zion was the founder and president of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, and established an extremely close relationship with the Malach, following his directives in the running of the yeshivah.

Reb Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz saw the Malach as a prime example of the synthesis of Torah learning and Chassidus with which he hoped to indoctrinate his talmidim, and encouraged them to meet the Malach. In time, a large group of talmidim became close followers of the Malach.

During the years 1934–35, when Reb Shraga Feivel was ill and forced to recuperate in Liberty, New York, the Malach’s followers began to implement his ideals, growing long peyos and beards and wearing long coats and tzitzis over their shirts. They refused to attend secular classes and Reb Shraga Feivel worried that their extreme appearance and behavior would discourage other American parents from sending their children to the yeshivah.

Eventually, these bochurim were asked to leave Torah Vodaath and in 1936, the yeshivah of the Malachim, Nesivos Olam, was founded.

In hindsight, the disagreement between Reb Shraga Feivel and the Malach is a perfect example of a machlokes l’sheim Shamayim, a disagreement for the sake of Heaven, of which the Mishnah tells us “sofa l’hiskayeim,’ that both sides will ultimately endure.

Torah Vodaath was the yeshivah that shaped the American Torah world, of which Reb Shraga Feivel was one of the prime architects. The Malachim were largely responsible for the acclimation and success of the many chassidic groups that flourish until today.

The Nesivos Olam yeshivah was headed by Reb Yankel Schorr, a close talmid of the Malach, and a brother of the Rosh Yeshivah of Torah Vodaath, Reb Gedalya Schorr.

In 1938, the Malach passed away on the first day of Shavuos. On the second day of Yom Tov, he was accompanied on his final journey by just a few close talmidim and his children, and he was laid to rest at the Riverside cemetery in Lodi, New Jersey.

His chassidim decided not to appoint a new Rebbe, but they united under the leadership of Reb Yankel Schorr, forming a kehillah based on the minhagim of the Malach, which were primarily those of the earlier Rebbes of Lubavitch.

The Malachim’s cheder underwent much difficulty due to their refusal to have a secular studies program. They were hounded by the government, until they eventually reached an agreement with the Tzelemer cheder to join their secular studies program on paper.

In time, many of the original families of Malachim joined the larger chassidic groups, such as Satmar, whose principles they identified with.

When Rav Schorr passed away in 1980, leadership of the beis medrash passed to Rav Mayer Weberman, son of Reb Ben Zion, who still serves as Rav.

In Monsey, the beis medrash of Rav Chaim Flohr also maintains the minhagim of the Malach, with the strong emphasis on the philosophy and minhagim of Chabad. In addition, the Cheder Tashbar in Monsey, which Rav Flohr heads, has no secular subjects in their curriculum, in accordance with the view of the Malach.

To say that the Malachim community is flourishing is wrong, as it has largely been swallowed up by larger kehillos around it. In truth, however, that is the greatest testimony to its success, for the Malach never meant for it to be a Chassidus unto itself; he just wanted there to be chassidishe Yidden in America.

Thanks to his vision, there are.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 191)

Oops! We could not locate your form.