Torah Quest USA

| September 5, 2023New Jersey veterinarian and expert baal korei Michael Segal's quest to lein the weekly parshah in all 50 states

Photos: Personal archives

Like so many other 12 year olds, Michael Segal of Hollywood, Florida, prepped extensively for his 1997 bar mitzvah under the tutelage of the local Young Israel’s Rabbi Edward Davis. He diligently reviewed the leining of his parshah, Metzora, even doing a practice run in a German castle while accompanying his grandparents on a visit to a friend.

But while most bar mitzvah boys are grateful to make a baruch shepetarani of their own after a single reading of their parshah, Segal had other plans. Just weeks after his official debut at the bimah, he leined the first two aliyos of parshas Pinchas while visiting his grandparents in New Jersey, giving them the opportunity to share their nachas with their friends who hadn’t been able to make it down to Florida for his bar mitzvah. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Segal continued leining the occasional aliyah at the Young Israel’s teen minyan. After finishing ninth grade at Katz Yeshiva High School in Boca Raton (known at the time simply as Yeshiva High School), he started taking on full parshiyos, a commitment he kept to when his family relocated to Paramus, New Jersey.

Acquiring new techniques that allowed him to master a parshah more effectively was a game changer for Segal, who was soon leining a full parshah every five to seven weeks. By the time he went to Israel’s Yeshivat Har Etzion as a gap-year student, he was proficient enough to pass the test to serve as a baal korei at the yeshivah’s main minyan.

Week after week, Segal’s passion for the parshiyos grew, and by the time he was finishing veterinary school at age 27, he decided to up the ante and lein every sedrah in full, on Shabbos, before his 30th birthday. He achieved his goal by leining parshas Ki Sisa in February 2014, two months ahead of his milestone birthday. With that under his belt, Segal was ready to tackle his next long-term project.

With the total number of US states and overseas territories the same as the parshiyos in the Torah, Michael Segal set out to lein in each of them. The week of Behar-Bechukosai in New Hampshire’s Chabad of Manchester, 2015

Beyond the Quest

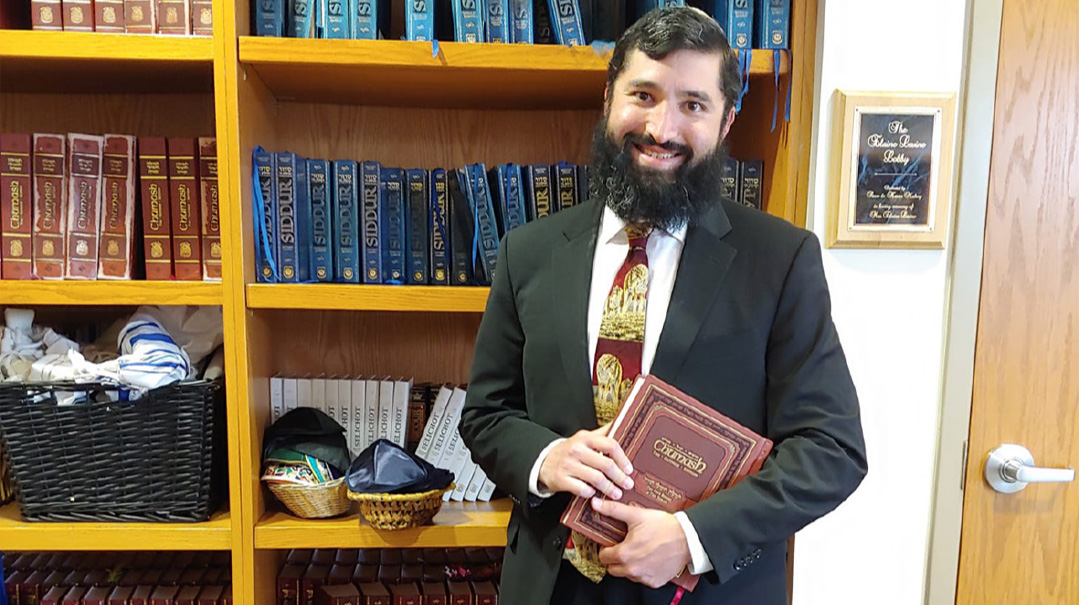

A Teaneck, New Jersey, veterinarian, Segal has served as shaliach tzibbur for the Yamim Noraim since 2004, both locally and in Ithaca, New York, during his college years. He has been one of the main baalei korei at Teaneck’s Congregation Rinat Yisrael since 2020, and there have been Shabbosos when he’s leined at three different morning minyanim. Segal has also taught bar mitzvah boys to lein, demanding excellence from his students much the way Rabbi Davis did from him more than 25 years ago.

Segal took a forced break from leining when Covid hit, but once lockdown rules eased, he was able to offer his services once again at multiple local minyanim. A Paramus resident at the time, Segal would don his sneakers and trek five miles to Teaneck to lein; today, he is happy to walk more than three miles from Teaneck to Englewood to serve as the baal korei there as well.

Given Segal’s passion for leining the Torah, it comes as no surprise that one of his most prized possessions is a small pre-1750 Torah scroll that was gifted to his great-grandfather for saving the Jewish community of Leutershausen, Germany, during the war years. Segal doesn’t know much about his great-grandfather’s act of heroism, the origins of the scroll, or how it survived the Holocaust, and while its letters have faded over the years and it is no longer kosher, he used it to lein at home during the Covid lockdowns in lieu of a Chumash. He has even caught a mistake that appears to date back to its original writing — a lamed that appears in the second aliyah of parshas Shelach in place of a beis.

Segal looks on as a student leins for his bar mitzvah. While most boys are happy to just get through it, from the Shabbos of his own bar mitzvah, Michael made the weekly parshah a lifetime project

Unusual Mooove

Segal majored in animal sciences at Cornell University and did his postgraduate studies in food animals at University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Despite his busy schedule, he made sure to keep up with his leining, stepping up to the bimah often in college and graduate school.

While nice Jewish boys don’t typically end up as veterinarians, it seemed the logical career choice for Segal, who had always had an interest in dairy cows. But with the industry lagging when he earned his veterinary degree in 2011, Segal took a research position that focused on pigs and poultry instead. Segal now works in field of companion animal clinical medicine, concentrating primarily on dogs and cats, though his patients have also included bearded dragons and various other birds and animals.

On one occasion, Segal had to submit an online evaluation of his work as an employee of Phibro Animal Health Corporation, and he wrote that he had been performing research on turkeys. The system rejected Segal’s submission, informing him that his responses violated the system’s offensive language checker, because the word “turkey” can sometimes be used to insult a person’s intelligence.

“It suggested that I change ‘turkeys’ to ‘misguided people,’” recalls Segal with a chuckle. “After that it became a running joke for Thanksgiving that I needed to pick up a ‘frozen misguided person.’ ”

During the Covid lockdown, leining at home from the Torah scroll his grandfather rescued during the Holocaust. While the scroll is no longer kosher and some letters have faded, it was another link in an eternal chain

State of Mind

After checking off his parshiyos project in 2014, Segal was ready to set another long-term goal, and multiple facets of his life conveniently came together as he contemplated his options. As an eighth grader, he had been a member of his school’s geography team, which placed second in the Miami-Dade County finals, and his work as a veterinarian involved considerable travel to remote locations for meetings, conferences, and research.

Viewing both of those interests through the prism of his leining, Segal couldn’t help but notice that the total number of major United States overseas territories and states and the number of parshiyos in the Torah were the same: 54. (Segal is one of many who consider the Northern Mariana Islands and Guam to effectively be one overseas territory, not two, given their long, shared history.) Appreciating the difficulties of trying to get a minyan in places like American Samoa, he started toying with the idea of doing a complete Shabbos leining in each of the 50 states.

The quest wasn’t just about personal bragging rights — it would allow Segal to spread the light of Torah from Hawaii to Maine, from Alaska to Florida, and everywhere in between.

Of course, the concept presented certain problems, the most prominent of which was arranging a minyan and getting a kosher sefer Torah in rather remote outposts of Judaism. While he already had already leined in seven different states, the prospects of following suit in places like Iowa and South Dakota seemed more than a little daunting.

Segal’s mom, Rebecca, was equally skeptical, questioning his sanity when he shared the idea of a nationwide adventure with her. But with a friend egging him on, Segal’s Torah quest officially began in the spring of 2014.

Having already done full Shabbos leinings in New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Florida and Texas, states with sizable Jewish communities of their own, gave Segal a head start on his quest, and he had even been a Shabbos baal korei in Seattle, Washington, as well. But the fact that Segal had previously leined in Nebraska is a story unto itself, one that took place in February 2014.

State #32. Outside Chabad Champaign-Urbana in Illinois on the week of Chayei Sarah in 2017

Good Shabbos, Nebraska

With just Terumah and Ki Sisa still outstanding in his mission to lein every parshah before his 30th birthday, Segal had already lined up the shuls where he would read from the Torah on those two weeks and had made all the arrangements for a gala kiddush to celebrate his accomplishment. Even discovering that he needed to be in the Midwest for work on the week of parshas Terumah didn’t appear to be a problem, with Segal figuring he’d fly home from Des Moines, Iowa, on Thursday night.

But Segal hit a roadblock when a blizzard slammed the Midwest, cancelling his flight. With his 30th birthday just weeks away, waiting another year to lein Terumah just wasn’t an option, so Segal started looking for airports within a four-hour drive of Des Moines that had flights going east.

“I found a flight from Omaha, Nebraska, so I picked up a car and drove through the blizzard, holding on with both hands,” says Segal.

Segal made it to Omaha’s Eppley Airfield and was thrilled to see the plane he would be taking to Newark pulling up to the gate from Chicago. Exhausted from his 135-mile drive, he boarded his flight, collapsed in his seat, and fell asleep.

“When I woke up, I saw that we were on the ground, and I thought that was a good thing, until I saw them pulling the bags off the plane and I realized we hadn’t even taken off yet,” recalls Segal. “They canceled us ten minutes later. I knew there was no way I was getting back to Teaneck for Shabbos. I called the gabbaim in Teaneck to let them know I wouldn’t be leining.”

Moving onto Plan B, Segal tried to reach Omaha’s Rabbi Jonathan Gross, hoping to be able to lein Terumah in a local shul that weekend. When his attempts failed, Segal took a taxi to a hotel about two miles from the local Jewish community and did some work on his computer while waiting to check in. He tried Rabbi Gross yet again, this time hitting pay dirt.

“I needed that parshah,” explains Segal. “Rabbi Gross told me that whether or not he could put me up for Shabbos depended on checking out my references, but that I was definitely leining that week, because otherwise he would have to.”

Rabbi Gross’s gracious Omaha welcome also included having Segal take part in “Good Shabbos, Nebraska,” his interactive Shabbos morning in-shul derashah, featuring interviews with a variety of guests.

Traveling to Minnesota for a work-related conference in September 2014, Segal stayed an extra Shabbos to log his first new state for his 50-states quest. It was easy enough to find a shul where he could offer his services as a baal korei in St. Louis Park’s thriving Jewish community, and shul gabbai Rafi Geretz happily offered to help Segal in his quest, explaining that St. Louis Park’s residents try to lend a hand whenever possible for the smaller Jewish communities in the area.

“He told me that they feel a sense of responsibility to the Jewish communities in the Dakotas, and that when I wanted to lein there, I should let him know and he would run a shabbaton that weekend to help make a minyan,” recalls Segal, who had no idea just how much help he was going to need to cross the Dakotas off his list.

State #19. In summer 2015, from Omaha to North Dakota in a Camaro convertible loaded with siddurim, Chumashim, and a tallis-wrapped Torah

Dakota Quotas

While there is a Chabad center in North Dakota, Segal was well aware that there were no guarantees that there would be either a Torah or a minyan in town on any given week. Even on the Yamim Noraim, there are only minyanim in North Dakota by day, and they require the participation of eight imported guests to bring the number of men up to the requisite ten.

Segal put Fargo, North Dakota, on his itinerary in advance of an August 2015 research trial business trip in Nebraska, and Chabad’s Rabbi Yonah Grossman assured him that he put together a proper minyan for that week. With his professional obligations completed, Segal drove more than six hours to Fargo in a white Camaro convertible loaded with siddurim, Chumashim, and a tallis-wrapped Torah, all borrowed from an Omaha shul. Out of respect for his precious cargo, Segal kept the top of the Camaro up and the radio off for the 13-hour round trip.

As it happened, getting a minyan turned out to be anything but simple, with things coming down to the wire as the all-important tenth man, someone who was passing through Fargo, decided to stay for Shabbos just an hour before shkiah. There were actually 11 men present in shul when Segal stepped up to the bimah to lein parshas Ki Seitzei, and ironically enough he was the only non-North Dakotan.

Still, getting a minyan in Fargo was infinitely easier than putting one together in South Dakota, Segal’s tenth state. At the time, there was no rabbi or even an Orthodox shul anywhere in South Dakota, with Rabbi Grossman doing double duty as the spiritual leader of both Dakotas. When Segal scheduled another trip to Omaha in January 2015, he decided to brave the cold and make the three-hour drive to Sioux Falls to add another state to his list. Hoping to help make a minyan, Rabbi Grossman gave Segal the name of two Israeli men who ran competing kiosks in local shopping malls, along with some cautionary words.

“He warned me they wouldn’t be part of the same minyan,” says Segal. “I had no clue if he was joking or not.”

As Segal soon found out, he wasn’t. The first guy was thrilled to hear about Segal’s quest, offering to bring in his Jewish workers and to host the minyan in his house, but only if his competitor wasn’t in attendance. The second kiosk owner expressed the same sentiment, leaving Segal in a quandary.

With no choice, he started working the phones, an effort that turned out to be disappointing, to say the least. Ari Maccabee, a local, was difficult to reach by phone, while Rabbi Grossman was unavailable to travel down to Sioux Falls the weekend of parshas Va’eira. Another potential prospect contemplated walking ten miles each way to the shul along with his expectant wife to help Segal out, but ultimately sent his regrets.

A nervous Segal did the only thing he could do — he davened.

“I said, ‘HaKadosh Baruch Hu, I always need Your help, but I really need You now,’” Segal remembers.

And just like that, things started falling into place. The president of the local Reform shul managed to find two men who were halachically Jewish. Segal finally reached Maccabee, who agreed to come, and Geretz, the St. Louis Park gabbai, decided to come to South Dakota with his 14-year old nephew and his eight-year-old son, all of whom were willing to make the four-and-a-half mile walk from their hotel. Together with the kiosk owner’s three employees, Segal was finally optimistic about having a minyan.

“I started thinking maybe we would have a miracle in Sioux Falls,” Segal says.

By the time Shabbos arrived, Segal had his ten men, but as the Friday night meal wound down, three of the four kiosk employees told him they planned to sleep late the next morning and wouldn’t be showing up to davening.

“I switched to Hebrew and said, ‘Maybe Mashiach hasn’t come yet because he wants a minyan in Sioux Falls,’” says Segal. “When they understood I had no minyan without them, they decided to come, and we actually ended up with 12 people.”

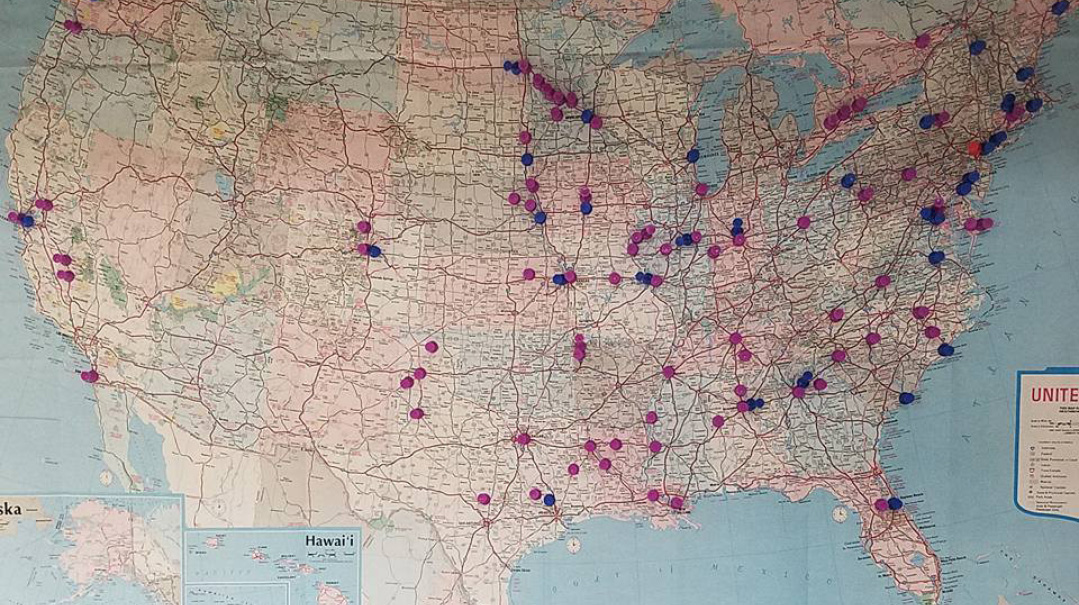

Halfway through the journey, blue pins mark the map over Segal’s desk, showing states in which he had already leined

Tenth Man

Segal has been in Iowa, the epicenter of the world’s swine industry, many times for work purposes, and has spent multiple Shabbosos there. (In fact, Lubavitch of Iowa’s Rabbi Yossi Jacobson has jokingly told him on more than one occasion about a midrash that says pigs will be kosher in the times of Mashiach, positioning Segal as the Jewish community’s go-to veterinarian.)

Segal arranged a Shabbos Chayei Sara visit to Des Moines in November 2014 around an Iowa conference, hoping to nail the ninth state of his quest. But during the Friday night seudah at Rabbi Jacobson’s home, Segal discovered that his host wasn’t sure if they would have a minyan, because he didn’t know if the tenth man he had been counting on had actually made it to Des Moines for Shabbos.

Segal kept counting heads as Pesukei D’zimra progressed the next morning, and he was relieved to have made it past ten by the time the tzibbur was up to Yishtabach. But while there were clearly 12 males over bar mitzvah age in the room, no one went up to the amud, and Segal turned to a fellow mispallel to inquire about the delay.

“You see that family there?” the man said to Segal, pointing to four clearly related individuals, all of whom had long peyos. “They’re working with a rabbi in Des Moines and are converting, so none of them count.”

With just eight men in his minyan, Segal watched the door, willing it to open. In time, a ninth man sauntered in, and everyone waited with baited breath to see if the tenth man would show up to complete the minyan.

“He finally came in, in an undershirt,” says Segal. “It was amazing to see. The guy with the Bat Ayin peyos didn’t count for the minyan, while the guy wearing the undershirt did. It was a good lesson in not judging a book by its cover.”

It was déjà vu all over again in Idaho, Segal’s 48th state. While the local Mormon community was extremely accommodating of Boise’s Jewish residents, even giving them space to daven, pickings were slim when it came to making a minyan.

Arriving in Idaho in February 2023 with plans to lein parshas Terumah, Segal was grateful to see more than ten people in town for Shabbos Friday night. As the Shabbos meal wound down, he talked up his quest to the man sitting next to him, hoping he and his sons would be motivated to return for davening the next morning.

What happened next took him by surprise. “When they left the rabbi said to me, ‘I know you’re pushing this with him, but just know that his sons don’t count because his wife isn’t Jewish,’” recalls Segal.

After the Shabbos in Anchorage, Segal took a scenic drive south to Seward along the Turnagain Arm waterway

The Frozen Chosen

If Segal had to choose his favorite state experience, West Virginia, number 46, would be the winner hands-down. Considering the 376-mile distance from home was far shorter than many of the other places he visited, Segal never expected his trip there to be possibly the most difficult one of his quest.

Over the years, Segal had reached out to Rabbi Zalman Gurevitz of the Rohr Chabad Jewish Center in Morgantown on multiple occasions, hoping to scare up a minyan in West Virginia. While Rabbi Gurevitz was thrilled by the idea of having a professional baal korei in his shul for a Shabbos, he warned Segal that pulling together a minyan was always difficult and suggested they keep in touch to find a week when the odds would be in their favor.

As the number of states still to be visited began dwindling, Segal decided to take matters into his own hands. He reached out to Rabbi David Merkin of Passaic, New Jersey, hoping he would help him make a minyan in Morgantown, West Virginia, for Shabbos Chanukah 2022.

A former Pittsburgher, Rabbi Merkin had previously sent five local yeshivah students to Youngstown, Ohio, to help Segal make a Shabbos minyan in March 2016. Reasoning that the distance from Pittsburgh to Morgantown was just a few miles farther than to Youngstown, Segal contacted Rabbi Merkin about trying to get some students to West Virginia. At Rabbi Merkin’s suggestion, Segal called Rabbi Gurevitz to find out how many men he actually had in Morgantown and if he could provide accommodations for the yeshivah boys.

It seemed that Segal had hit the jackpot. Rabbi Gurevitz told him that, as it happened, seven bochurim were actually planning on coming to Morgantown that Shabbos in a newly commissioned mitzvah tank. The Chabad shaliach apologized for not reaching out to Segal to let him know of the potential for a minyan that weekend, explaining that the weather forecast called for a blizzard and frigid temperatures, which meant he couldn’t guarantee that anyone would show up to Shabbos morning davening.

With 45 states already under his belt, Segal was willing to take the chance to make West Virginia happen. He drove in wintry conditions to Morgantown and was elated Friday night to see that he had enough people for a Shabbos morning minyan. There were still plenty of l’chayims being tossed back as Segal headed back to his hotel, but the next morning, with temperatures hovering below zero and the wind chill at 40 below, the seven Chabad bochurim were all MIA when it came time for davening. As the minutes ticked by, they started trickling in, with the head count making it up to nine, until at long last, Segal got a Chanukah miracle of his own, when the tzenter trudged in. His beard was glistening with actual icicles, and at first, Segal thought he had fallen in the snow.

“It turned out that he wanted to go to the mikveh,” says Segal. “He didn’t want anyone coming with him and trying to convince him it was a bad idea so he went by himself.”

With no eiruv, the bochur didn’t even have a towel to dry off with after emerging from the Monongahela River, which was dotted with ice chunks and the floes. As he made the half mile walk back to Chabad, his hair, his beard and wet clothing all froze.

“By the end of lunch, he still couldn’t feel his fingers, but at least he helped make the minyan,” quips Segal.

Staet #50. Outside Congregation Shomrei Ohr in Anchorage, Alaska, August 2023. Finally, the finish line

50th Gate

The final two states of Segal’s quest were Wyoming and Alaska, places where the best odds of getting a minyan were during the summer tourist season. Wanting to ensure he could finally complete his Torah quest, Segal arranged to spend two Shabbosos in each of those two states, reasoning that on the off chance that a minyan didn’t materialize the first week, he would still have a second opportunity.

Things went smoothy for Segal on his first Shabbos in Wyoming this July, and counting heads at the Friday night Chabad minyan in Jackson, he identified 11 men over bar mitzvah age that he felt were likely to return the next morning for davening. Thankfully, getting a minyan was no problem on Shabbos morning and Segal leined Mattos-Masei, the longest double parshah in the Torah.

Interestingly enough, it is also the parshah Segal leined most out of state; he leined it in Washington, Delaware, Missouri, and Indiana as part of his quest.

“On a random week in the summer, no one needs help when it comes to leining Vayeilech, which is just 30 pesukim long, but when you offer to do Mattos-Masei, the rabbi or the baal korei is usually more than happy to get the week off,” explains Segal.

That first Shabbos in Jackson, Segal met the rabbi of the Conservative shul in Overland Park, Kansas, who was vacationing with his family. The rabbi asked if he’d leined in Kansas, and Segal assured him he had, with back-to-back leining in two shuls on the same week.

“I had originally reached out to the Modern Orthodox shul in Overland Park,” says Segal. “They were having a high school shabbaton that weekend and told me they were saving the leining for a high school kid, so I reached out to Chabad instead and arranged to be the baal korei there.”

Davening in the Modern Orthodox shul that Friday night, Segal was asked to come back the next morning to lein. Having already committed to Chabad, he expressed his regrets, since he couldn’t possibly be in two places at the same time.

“They told me not to worry,” recalls Segal. “Chabad starts so much later that I would be able to do both.”

Segal spent a week enjoying Wyoming’s national parks — Grand Teton and Yellowstone — with his father and sister, Bruno and Debra Segal, before returning to Jackson for Shabbos Devarim as well, leining Shabbos morning with a minyan of 13 men. But as excited as Segal was to get state 49 under his belt, there was no denying the fact that his eye was on the prize, as Alaska loomed large on the horizon.

On August 15, Segal boarded a flight to Anchorage. Accompanied by several family members who didn’t want to miss the culmination of his nine-year quest, he spent a whirlwind three days taking in the majesty of Alaska’s fjords and glaciers while reveling in the opportunity to see all kinds of whales, massive trumpeter swans, and moose so large that their six-foot-wide rack of antlers can weigh in at 40 pounds. But even visiting remote islands and experiencing a plane ride from Anchorage to Juneau — what Segal described as the most beautiful flight he has ever taken anywhere in the world — there is no question that the highlight of the trip was going to take place on Shabbos, August 19, at Congregation Shomrei Ohr – Chabad, also known as the Lubavitch Jewish Center of Alaska.

While minyanim had proven to be difficult for Segal in many places during his quest, things went just as smoothly in Anchorage as they had in Wyoming. Segal, his relatives, the rabbi and his son-in-law totaled six men, so getting to ten was fairly easy given how many locals and tourists were in town that weekend.

As he leined the final words of parshas Shoftim, Segal had mixed feelings, appreciating that even as he was celebrating the completion of a monumental accomplishment, the book was far from closed on his quest.

“I realized at that moment that, in the same way that the Hadran we say at a siyum talks about returning to the same study again, I was looking forward to coming back to the places where I was able to spread Torah, to rekindling the friendships forged over the past nine years and to revisiting these 54 parshiyos that eternally stand the test of time,” he says.

As his uncle started pouring l’chayims from a bottle of Cardhu he had picked up in honor of the occasion, Segal accepted congratulations from his fellow mispallelim, relative strangers who became instant friends as they bonded over his celebratory achievement. Among the visitors was a group of six people who had come to Alaska for the Anchorage RunFest marathon that weekend.

“One of them told me he was working his way toward running a marathon in every state, and this was his 43rd state,” says Segal. “I guess in a way, I was doing a marathon as well, only mine was a Torah marathon.”

While Segal officially completed his Torah quest on the Shabbos of parshas Shoftim, his first Shabbos in Anchorage, it should come as no surprise that he wasn’t going to sit on the sidelines the following week. Segal was up at the bimah to lein Ki Seitzei, yet another opportunity to chap a mitzvah while doing something he loves.

Preparing to lein in Anchorage’s Shomrei Ohr. Segal, the rabbi’s family, and a few touirists made the minyan

Next Up?

While his nationwide Torah quest is now in his rearview mirror, Segal isn’t even considering the notion of hanging up his yad and retiring. Close friend Rabbi Perry Tirschwell put Segal in touch with a contact who has leined in 35 different countries. The idea is intriguing to Segal, who has already leined in Czechoslovakia’s Altneuschul, the world’s oldest continuously functioning shul, and in Copenhagen’s Great Synagogue — but only up to a point.

“I’m not going to try a 180-country quest,” explains Segal. “Getting a minyan with a Torah in every country, not to mention places that aren’t so friendly to Jews, just isn’t realistic.”

For now, he is toying with the idea of seeing if he can lein all of Chamishah Chumshei Torah in a single day, and is also setting his sights on the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, which will be hosting a veterinary conference early next spring. Also on Segal’s radar is Canada, and while he has every intention of leining in the provinces that are relatively close to his New Jersey home, he acknowledges that others may not pan out for a variety of reasons.

“Yukon, for example, is a huge territory that is very spread out and has a population of less than 35,000 people,” says Segal. “Major roads are in poor shape because there is minimal tax money, and you can drive 100 miles there and not pass another car. To say that there are barely any Jews there would be an understatement, which would make getting a minyan extremely difficult.”

Lessons from the Bimah

It’s been nine years since Segal started racking up states to complete his quest, and he knows he’s gained so much more than just bragging rights.

“People often asked me why I didn’t just lein on a Monday or a Thursday, which would have been so much easier than spending Shabbos in 50 communities and trying to pull people together in 50 different places,” observes Segal. “But the truth is that making those minyanim brought people together.”

Having met so many interesting individuals during his journey brought home a very important lesson for Segal.

“Wherever you go, whether it’s in Iowa or New Jersey, there are things that make us different — but there is so much about us that is the same,” notes Segal. “Wherever you are in the world, other than a few weeks in Israel, we’re all reading the same parshah, a reality that, Jewishly speaking, brings us all together, no matter who or where we are.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 977)

Oops! We could not locate your form.