Ain’t Gonna Work on Saturday

| August 29, 2023What ultimately facilitated shemiras Shabbos in the United States

Title: Ain’t Gonna Work on Saturday

Location: New York

Document: The Jewish Forum

Time: 1925

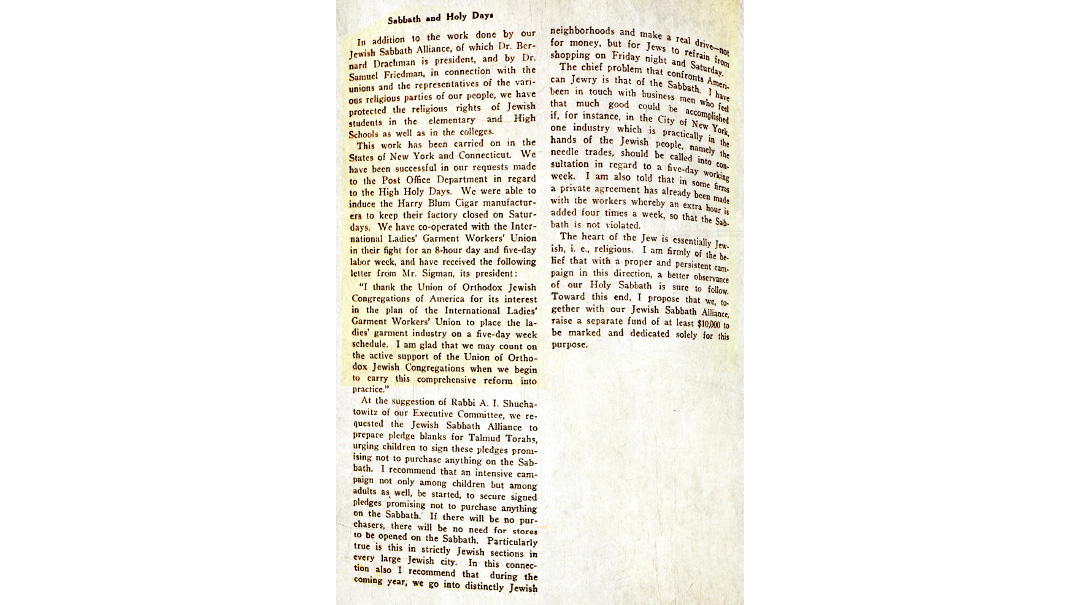

AS millions of Eastern European Jews arrived on American shores between 1880 and 1924, they found that in the “land of freedom and opportunity,” Shabbos observance was nearly impossible. Immigrants who took jobs in New York’s burgeoning garment industry were often told “not to bother coming back on Monday if you don’t show up on Saturday.” While there were occasional instances of heroic commitment to Shabbos observance, most succumbed to the harsh realities.

And yet when Holocaust survivors came to America after the war, the situation had changed significantly. Employers were much more open to hiring Shabbos-observant workers. What had changed?

Credit must go to the labor unions.

The rapid growth of industries like railroads, manufacturing, mining, and textiles in the 19th century came about when working conditions for employees were much worse, wages were much lower, and the workweek often extended to seven days. In response, workers began to organize into labor unions.

In 1886 they coalesced into the American Federation of Labor, whose first president was a Jewish immigrant from the Lower East Side named Samuel Gompers. Over the ensuing decades, labor unions demanded improved working conditions, livable wages, and shorter work days and weeks. They negotiated contracts with employers, and held strikes when their demands weren’t met.

The first five-day workweek in the US was initiated in 1908, by a New England cotton mill, to accommodate its Jewish workers. The infamous Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire in March 1911, which killed 146 mostly Jewish and Italian workers, drew widespread attention to the inhumane conditions in the garment industry. This spurred the growth of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. Much of the ILGWU’s membership, and nearly all its leaders — Rose Schneiderman, Benjamin Schlesinger, Morris Sigman, and Brisk-born David Dubinsky — were Jewish immigrants who had grown up in traditional homes in Eastern Europe.

In 1926 Henry Ford instituted the two-day weekend, unilaterally shutting his factories on Saturday and Sunday. Three years later, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America demanded and received a five-day workweek for its members. Like other New York unions, it was Jewish dominated, led by a Slabodka alumnus named Sidney Hillman for its first thirty years.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal did much to formalize union demands and improvements in working conditions. The landmark 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act mandated a 44-hour workweek, later amended in 1940 to 40 hours. The five-day workweek and two-day weekend were soon adopted nationwide.

This societal sea change finally made keeping Shabbos possible on a large scale, and many among the immigrant generation no longer had to face the difficult choice between Torah observance and watching their family go hungry. It’s a great historical irony that it was the largely secular Jewish-led labor unions, along with the anti-Semite Henry Ford and FDR’s New Deal, that ultimately facilitated shemiras Shabbos in the United States.

A New Dealer from Slabodka

Union leader Sidney Hillman was born in Zager, Lithuania, and studied at the local cheder. At 14 he entered the Slabodka yeshivah, but left traditional observance and joined the socialist Bund in 1903. After the failed 1905 revolution, he fled Russia for the United States in 1906. In addition to heading the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, he supported FDR’s New Deal, advising Labor Secretary Frances Perkins on the enactment of the Fair Labor Standards Act. He also founded the Labor Party of America in 1936 with David Dubinsky. Albeit unintentionally, Hillman’s union activities did much to enable Shabbos observance in America.

The Sabbath Law

Governor Nelson Rockefeller and the New York state legislature brought the decades-long struggle over Shabbos observance to a final close in 1971. Under the new law, private sector employers couldn’t discriminate against employees who left early on Friday or took Jewish holidays off, nor could they refrain from hiring such employees; and they were required to allow them ample travel time. Rabbi Moshe Sherer of Agudath Israel of America had advocated strenuously for the law for several years, and declared its passage “a historic breakthrough in the field of legislation affecting Jewish rights.” He praised Rockefeller and his staff “for the sensitivity they displayed to the needs of the religious Jewish community by tirelessly shepherding this landmark Sabbath bill through the labyrinth of the state legislative bodies.”

Not So Simple

Early 20th-century activist Dr. Samuel “Shabbos” Friedman worked with Seventh Day Adventists and labor unions to enshrine the five-day workweek into law. The biography An Angel Cometh by Leonard S. Friedman tells of a 1922 meeting Dr. Friedman arranged to advance this cause.

Surprisingly, at least one leading member of the Agudas Harabbonim was opposed to the advent of the five-day workweek, based on a somewhat roundabout philosophy. He believed that at that time, Jews who desecrated the Sabbath by working had some extenuating excuse; namely, that they had to earn a livelihood, and that if they did not work on the Sabbath, their families might suffer privation. However, if the five-day week became effective and were to become an actuality, a great many of these people would still not observe the Sabbath. They would then be desecrating it without having a valid excuse. He felt that those who were sincerely devout were willing to make the necessary financial sacrifice to avoid employment on the Sabbath. The others who were not observant, he contended, would only sin without just cause, and he did not wish to be a partner to their sin.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 976)

Oops! We could not locate your form.