A Crown Passed Along

Mourning Rav Aharon Schechter

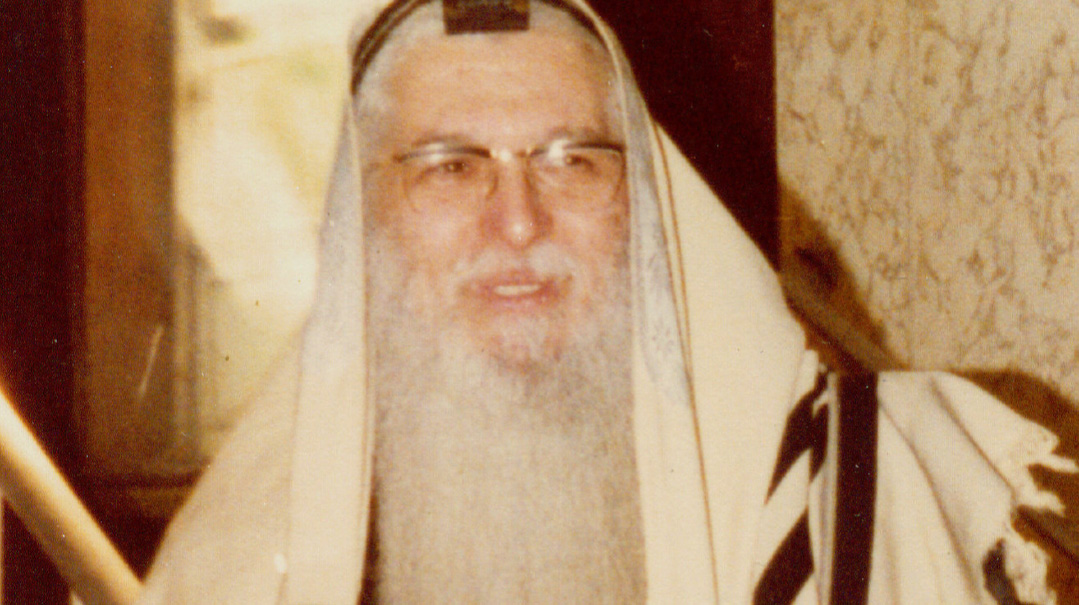

Photos: Mattis Goldberg, AEGedolim, Family archives

Rav Yitzchok Hutner believed that even in America, it was possible to nurture a ben Torah who would live a life suffused with the spirit and majesty of Torah. And when he relocated to Eretz Yisrael, he knew the yeshivah community he left behind was in good hands. Because Rav Aharon Schechter’s mission went way beyond shiur. Last week the Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin Rosh Yeshivah returned to the world of the angels, yet like true royalty, he not only lived an exalted life, but lifted up all those around him, making them bigger too

The mandate of a museum is simply to preserve what was.

But the Torah is Toras chayim, vibrant and alive, so it is not sufficient — or even possible — to merely safeguard it. Its beauty must be transmitted, conveyed and communicated to new generations, in ever-evolving languages.

But how can one safeguard the treasure chest while also sharing its riches?

If the guardian and the teacher are one and the same, someone who understands that there is but one treasure, then there is no paradox between protecting and also sharing.

It can work if the great talmid is also a great rebbi.

It can work if, like Aharon HaKohein, he does not change or veer — lo shinah. And like Moshe, his essence is that of “rabbeinu,” our teacher, a shepherd focused on the weakest of his flock.

It can work if one is like Rav Aharon Moshe Schechter.

Along with the formal shiur, Rav Aharon’s talmidim received so much more – he pulled them along together with him on his journey to greatness and character refinement

Rav Yitzchok Hutner came to a land of ambition and greed, people intoxicated by the freedom to serve or ignore, pulled to the gold rush they could see on the horizon.

To the children of those streets, Rav Hutner extended a hand and offered to lift them: a few of them followed him and were captivated by the beauty he helped them perceive, drawn by the symphony he allowed them to hear.

He created balabatim like he had seen in the Warsaw of his youth, working people who sat in offices between nine and five, but saw it not as a contradiction to the hours spent in shul learning or davening, those who perceived that this was not a double life, but a broad life.

Rav Hutner produced synagogue rabbis, sending forth talmidim armed not just with the knowledge and eloquence to teach, but also the confidence and courage to lead.

He fashioned mechanchim, great educators who had watched a master and wanted to share that light: Some would teach young and some would teach old, some teaching those close to home, and others bringing the truths of the beis medrash to those who had not yet tasted it. But all of them believed in the role, inspired to emulate their Creator.

Then, after two decades of teaching Torah to bochurim, the Rosh Yeshivah felt ready to introduce a new product to America: the derhoibbene ben Torah who would live the life of Yissachar, suffused with the spirit of Torah and the majesty of Torah.

With the vision of a military commander and the sensitivity of a loving parent, Rav Hutner planted his talmidim where he thought each could flourish.

Rav Aharon, he kept in yeshivah.

Reb Yosef and Fruma Rochel Schechter had the hasagos, well understanding this concept of a ben Torah. Joe Schechter was one of the few balabatim in America to stand behind Rav Leib Malin, who was building a replica of the yeshivah he’d seen in a different world, this one in Brownsville of the 1950s.

Beis HaTalmud was not one of the especially popular causes, because in their hearts, balabatim would say, “What do they have already — a small group of men in their fifties, let them go to work…!” I remember Rav Leib coming to collect money, accompanied Rav Reuven Levovitz and two balabatim, Reb Moshe Swerdloff and Reb Yosef Schechter. All three of these men merited sons who are gedolei Torah and yirah… I would only add that these were clearly people of stature, because Rav Leib would never have tolerated a hint of chanifah, and he would not have allowed them to accompany him had they not been worthy… (Rav Michel Shurkin, Megged Givos Olam.).

Born in 1928, their son Aharon graduated Rabbi Yitzchok Schmidman’s Toras Chaim and then continued onto the high school of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin. Over the next few years, he met his rebbi, was drawn to his rebbi, captivated by his rebbi, and finally, he was completely davuk in his rebbi, as if attached.

“I don’t know how many rebbes had chassidim as attached to them as Rav Aharon was to the Rosh Yeshivah,” recalls Rav Dovid Cohen, himself part of that initial chaburah and a founding member of Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin’s Kollel Gur Aryeh. At the age of 16, young Dovid Cohen heard a shtickel Torah from Aharon Schechter, a bochur few years older than he, that moved him so: at that moment, hearing the long Tosafos in Bava Metzia, the Teshuvos Rabi Akiva Eiger and the Nesivos about the din of bar metzra, he knew that he was home, that he would not leave the beis medrash.

The Torah of Rav Aharon: beautiful, pristine, and alluring.

If Rav Hutner was producing bnei Torah that would sustain future generations, Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan was preparing the wives of those talmidim. Shoshana Leichtung understood the role she was being given, and she appreciated it.

They married in 1954, and just three years later, Rav Aharon wrote a sefer, a complex and intricate treatment of the Rambam’s Hilchos Beis Hamikdash. In the front, he writes of his wife: “Really, her name should appear on this sefer, as the pasuk says, ‘Give her from the fruit of her hands….’ It is thanks to her ahavas Torah that I have the serenity and clarity of thought to submerse myself in the tents of Torah: as Chazal say, ‘What is yours and what is mine, is hers.’”

The sefer is called Avodas Aharon, and in his haskamah, Rav Hutner reflects on the suitability of the name: “It is a name that expresses the distinctiveness of your spiritual essence, the way in which you combine the light of Torah and the light of avodah into a single light.”

The talmid had a unique way of processing his rebbi’s Torah, seeing not just abstract ideas, but concepts that obligated the heart and refined the person: Rav Aharon would get dressed in his bedroom each morning, but he would only recite birchos hashachar downstairs in the dining room, so as not to wake his wife.

In one ma’amar, Rav Hutner had suggested that since Torah must be learned with the intent to fulfill its words — “al m’nas lekayem” — it follows that a person can perform a mitzvah on one of two levels. He can do the mitzvah to fulfill Hashem’s will, or he can do it to fulfill the condition inherent in limud haTorah, essentially defining and validating the Torah learning.

If talmud Torah is keneged kulam, worth more than any mitzvah, said Rav Hutner, then it follows that the second level of kavanah outweighs the first, for it is gives the mitzvah the status of Torah.

And so, if he was going to integrate this kavanah into his performance of mitzvos, Rav Aharon reasoned, then he must first recite birchos haTorah before doing the mitzvah of tzitzis, since the observance of the mitzvah was itself part of Torah study. Therefore, upon waking in the morning, he got dressed — but without the tzitzis, which he brought downstairs with him, to put on only after reciting birchos haTorah. The tzitzis remained on top of his shirt, and that is how he wore them, encircled by Torah and avodah.

Rav Aharon said a shiur in the yeshivah during those years, but along with the formal shiur, his talmidim received so much more.

“Rav Hutner had many devoted talmidim, among them major geonim,” reflects a talmid of the era. “Rav Aharon was certainly bright, but his story was one of hard work, of diligence and toil, acquiring the Torah in the only real way — with long hours and exertion.”

Talmidim learned to marvel at the consistency. “It was a regular feature of summers in Camp Morris to watch Rav Aharon on Shivah Asar B’Tammuz,” recalls a talmid. “The vort in yeshivah was that all year long, Rav Aharon only ended first seder because there was Minchah, but on the fast day, Minchah was in the late afternoon — and so Rav Aharon learned until then, sitting from the beginning of first seder until seven p.m., seeing no reason to close the Gemara.”

“And there was nothing,” says another talmid, “that Rav Aharon would not do in order to help a bochur understand something in Torah. That was his essence and he gave himself away to that task.”

It was yet another expression of the avodah referred to in the title of his sefer: an eved, there to serve. An eved to the Torah and an eved to those who wished to understand it.

Avodas Aharon.

Rav Hutner had always dreamed of returning to Eretz Yisrael, and in the 1970s, he saw the opportunity. He was joined by his children, Rebbetzin Bruria and yblct”a Rav Yonasan David, while hundreds of talmidim in Brooklyn wondered what this meant for the yeshivah.

Rav Hutner understood the needs of everyone and everything he was leaving behind — a kollel and beis medrash, a high school and cheder, a kehillah of families who looked to him as children to a father — and he turned to his beloved Rav Aharon.

Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin would not just have a new rosh yeshivah, but a new melech, a king.

Sure, he was royal in appearance: the luminous smile, the dignified bearing, the air of graciousness, but that was just a reflection of his approach to life.

Like true royalty, he was never off duty.

One talmid of decades interacted with the Rosh Yeshivah as a bochur, a yungerman in the kollel, and then as an alumnus, having left yeshivah to go to work. “I don’t recall ever hearing him say, ‘It isn’t a good time now.’ Sometimes we had to wait while he spoke with someone else, but there were no off-hours. He saw himself as belonging to the people.”

And that meant all people. He was sick one day, so weak that he had to be helped into his bed. And as his children were ensuring he was comfortable, the doorbell rang.

The children hoped he would not notice, but he did. “Go see who is there, perhaps someone needs me,” the Rosh Yeshivah insisted.

It was a Yid — not a talmid or family member — in search of advice. The Rosh Yeshivah immediately sat up, ready to serve.

A talmid once described the wealth of a particular businessman. “He is so rich, that he has no phone in the office, everything is taken care of for him.”

“No phone means he’s wealthy?” asked the Rosh Yeshivah. “Not having a phone means he has no sense of achrayus — you don’t have a phone for yourself, but to make it easier for other people who might need you!”

There were no “lighter moments,” periods in which those close to him got to see him unwind. The avdus to which he had committed himself meant that he was either contemplating the open Gemara on his shtender or contemplating the Yid sitting across from him.

A meshulach could circulate in the beis medrash, a tired man holding a tattered letter of recommendation. But a true ben Torah never does things mindlessly, even a mitzvah like reaching into his pocket to remove a dollar to tzedakah — and so the Rosh Yeshivah would listen.

It was not uncommon to see the eyes of Rav Aharon — man of discipline and restraint — fill with tears as he heard a tale of woe. The Rosh Yeshivah did not cry in public and he was not prone to external displays of emotion, but the suffering of another Yid was personal.

(Although talmidim did not see the Rosh Yeshivah cry in public, there was a moment in 1990, when the aron of Rav Shlomo Freifeld was being escorted to Eretz Yisrael for kevurah. It was a rainy day and the freight door to the airplane had been closed, but Rav Aharon continued to stand there alone on the wet tarmac at JFK Airport, his anguish evident. “I lost my best friend,” he said to no one, then squared his shoulders and headed back to the car, a soldier returning to battle alone.)

More than once, individual collectors — not representing mosdos or organizations — benefitted from private parlor meetings or campaigns spontaneously spearheaded by the Rosh Yeshivah. He had heard them, and hearing creates new obligations to action.

Without speaking outside yeshivah, he was still a powerful figure in the life of the Klal: with Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock of Long Beach at an asifah

There was a period in which scores of bochurim came from Eretz Yisrael to learn in the yeshivah. And while they came to learn, the Rosh Yeshivah saw a responsibility beyond saying shiur.

Many of them had never done proper dental work, so he would send them to dentists and cover the costs. He understood that a basic command of the English language was necessary, so during bein hasedorim, he would teach them a new word or two.

True, he was the Rosh Yeshivah. There were others who could teach them English. But he was a rebbi, and they were talmidim, and there was an achrayus to make them whole.

Avodas Aharon.

It was an avodah, and it was his avodah. A few years after Rav Hutner moved to Eretz Yisrael, he confided in the yeshivah’s president, Reb Avrohom Fruchthandler, that he had great nachas from his talmid. “I am not only pleased that the oilem appreciates Rav Aharon, I am also pleased at how he is leading — he is not seeking the imitate me, but to do it in his own way.”

For the new Rosh Yeshivah, this too was part of the avodah.

During the first years, Rav Aharon said shiur klali, his talks masterpieces of clarity and precision, but when he learned Rav Hutner’s Pachad Yitzchok publicly, he would not add a single word or thought to that of his rebbi. He would simply open the sefer and read from inside.

It was only with time that he began to expound on the words and ideas, developing his own style.

In the car on the way to simchahs or events, he would often learn or rest, but even that was regimented. “Wake me up in seven minutes,” he would ask, and talmidim quickly learned that seven minutes did not mean eight minutes. As in every other area, he had made the cheshbon and it was precise.

If there was an activity that did not appear to be avodah, it might have been the music. “The Rosh Yeshivah had a song he particularly liked, Moshe Goldman’s ‘Pnei Le’elbon.’ We would sing it together in the car, and he would get very emotional,” remembers a talmid who often drove the Rosh Yeshivah.

But even that was an avodah, because it meant connecting with a talmid on the neshamah level.

The Rosh Yeshivah lived in contemplation, because, as he taught, a ben Torah’s every motion is consequential.

It was once decided to encourage a particular rebbi to give up his position and find a job more suited to his personality. Rav Aharon asked one of the board members to meet with the rebbi and inform him of the decision. The board member, knowing that it was unlike the the Rosh Yeshivah to pass off a difficult task to another, asked why the Rosh Yeshivah didn’t feel it more appropriate to have the conversation with the rebbi on his own.

“Because, think about it,” the Rosh Yeshivah said. “When you finish speaking with him, he’ll be extremely hurt. He’ll come to me, because he is my talmid, and even if I don’t think he should have that job, I do think he should be able to share his pain. But if I’m the one who lets him go, then where will he go to cry?”

A talmid who lived his life thinking about what his rebbi would have wanted from him: Rav Schechter was the moon to Rav Hutner’s sun

Like his rebbi, Rav Aharon did not speak publicly outside the walls of his own beis medrash, but somehow — without fanfare or hype, without bold proclamations or statements — the needs of a nation flowed through the yeshivah on Coney Island Avenue.

Newly arrived refugees from Iran or Russia were welcomed in the classrooms. The yeshivah was a pioneer in welcoming specialized classes for students who needed extra scholastic help, even from beyond its own student body. The massive annual Lev L’Achim asifah took place in the building, with talmidim expected to dedicate their Purim collection to the organization serving their not-yet-religious brothers and sisters in Eretz Yisrael.

At the Agudah convention one year, a respected speaker described a particular ideological battle in which the rabbanim were engaged. “The rabbanim feel strongly about this,” the speaker said, “but the Reform rabbis, l’havdil, feel the opposite.”

The Rosh Yeshivah looked up instantly and said a single sentence — the beginning and end of his Agudah Convention oratorical career. “We do not say l’havdil on a Yid,” he said.

Rav Hutner had recognized that Rav Aharon’s ability to reach individuals was an outgrowth of his insight into the needs and personalities of each one.

A girl from a secular background attended Bais Yaakov for a while, but she soon grew disillusioned and wanted to return to her old school and lifestyle. One of the askanim involved in helping her asked her to come discuss the decision with Rav Aharon Schechter. Neither of them had any connection with the Rosh Yeshivah, but he kindly told them they were welcome to come at their convenience.

When they arrived, the Rosh Yeshivah was inside his office speaking with someone, so they sat down in the waiting room. Minutes passed, and then a full hour. The girl grew irate, feeling that her time was being disrespected.

Eventually, the Rosh Yeshivah welcomed them to his room, and the askan described the girl’s situation. When it was her turn to speak, she couldn’t control her frustration. Rather than share her story, she shared her anger. “Why is it okay to tell people to drive into Brooklyn and then make them wait for such a long time?” she asked.

The Rosh Yeshivah smiled and he appeared to be genuinely pleased with her question. “Ahhh,” he said with delight, “this is the spirit of a bas Yisrael, the strength and boldness which has kept us going all through the years. A real bas Yisrael….”

One of the Rosh Yeshivah’s close talmidim, Rabbi Chaim Nosson Segal, married off a daughter. At the simchah, Rabbi Segal, who is rav in a shul in which many of the families were not religious at that time, introduced the members of his congregation to his rebbi. He mentioned that one congregant came to shul six mornings a week, davening with unusual kavanah. But on Shabbos, the man could not come, since davening started later and he had to get to work as the manager of a convenience store.

The reception line for brachos continued, and Rabbi Segal, father of the kallah, moved on to attend to other guests.

The next morning, this congregant told Rabbi Segal, “Wow, your rabbi sure loves me.”

It turned out that a few minutes after Rabbi Segal’s introduction, Rav Aharon stood up and began circulating in the hall, going from table to table, looking for the people from Rabbi Segal’s shul. Finally, he found the right table, and asked for the gentleman who came to shul six days a week, but not the seventh.

One man stood up, and the Rosh Yeshivah asked if they could speak. In a quiet corner, Rav Aharon listened as the man explained his situation and his reality. He was not ready to keep Shabbos. The Rosh Yeshivah nodded, and then went through the Saturday workday schedule and responsibilities, showing him how he could minimize chillul Shabbos wherever possible.

They covered the entire day and the workplace tasks. It turned out that even there, the man could reach for Shabbos, connecting with it even while managing a shabby convenience store in a sordid neighborhood.

Six months later, this man informed his boss that he would no longer be working on Shabbos or Yom Tov, and today, his children and grandchildren are religious.

One time, the Rosh Yeshivah needed a haircut, and during bein hasedorim, he asked a talmid to drive him.

In the car, the talmid confirmed that they were going to the barber.

“No,” said Rav Aharon, “we are going to the barbershop. Once we’re there, we’ll use whichever barber is available, because we can’t disgrace the one who is available by passing him over for another.”

Love, for all Yidden. And respect, for all people.

Like true royalty, he made other people feel bigger in his presence.

He articulated this one summer in Camp Morris, when some bochurim were playing around and broke a window. The newly hired director was upset by the reckless damage to camp property, but when he informed a hanhalah member what had happened, he was told to simply get the window fixed by the maintenance staff and not make a big deal about the incident.

This casual attitude brothered the new director even more and he conducted an independent investigation, finding out who the guilty bochurim were, then calling them in to reprimand them.

Soon after, he received a message that the Rosh Yeshivah wanted to speak with him.

Rav Aharon greeted him with a warm smile, then gently asked how it came to be that a member of the administrative staff was involving himself with the chinuch of a yeshivah bochur, something clearly beyond his responsibility.

The director spoke of the irresponsibility and carelessness of the bochurim involved. Still smiling, the Rosh Yeshivah said, “First of all, we have a shtickel mesorah here, a tradition in this camp, and that is, that boys will be boys. And second of all, we took you to be our director because you’re a ben Torah. A ben Torah has to understand that tochachah can only be given with a chibah yeseirah, an extra dose of love that comes along with it. But to give mussar without building a boy up? This is not our way here.”

That was it. Not just a response, but also a real-life example of how one can give mussar in a way that leaves the recipient feeling not censured, but loved.

Because mussar and chinuch are not about information conveyed, but a relationship deepened.

The Rosh Yeshivah once noticed a talmid sitting idly during mussar seder. He called him over to discuss it, and the talmid said that he had no chavrusah.

“Why don’t you learn alone?” the Rosh Yeshivah asked.

The young man replied that he found the words in lashon kodesh too hard to understand.

The next day, the Rosh Yeshivah approached this talmid with a gift he himself had purchased — a copy of Mesilas Yesharim with an English translation, inscribed and signed with love and blessing by Aharon Moshe Schechter.

On a Shabbos afternoon, the Rosh Yeshivah was heading home for Shalosh Seudos, surrounded by a small crowd of bochurim, when he spotted a few boys on a street corner, clearly from frum homes, smoking cigarettes. The Rosh Yeshivah said nothing and kept walking. But a full block later, the Rosh Yeshivah turned around and walked back without saying anything to his companions. The talmidim understood that he wanted to go back alone.

He approached the group of smoking boys and smiled. “Gentlemen, I want to tell you that ich hub eich leeb, I love you. My doors are always open to you.” Then, he turned once again back to his own talmidim.

With Rav Dovid Feinstein, who would speak admiringly of the emes and yiras Shamayim of his friend Rav Aharon

Like true royalty, he did not just live exalted — he lifted up all those around him, making them bigger, too.

“What I miss most,” a talmid commented during the shivah this week, “was how big he made me feel. He expected us to be big, but he also showed us that we had it inside us. Nothing — how we ate, where he ate, how we spoke and who we spoke with — nothing was small. If everything you do is important, then you start to realize that you, too, have worth.”

In the Rosh Yeshivah’s world, there was little use for pettiness or words spoken without consequence.

As a young man, he once saw a passenger on the city bus toss a soda can outside the window. He grew pensive at the sight. “To sully a glorious world is to be oblivious to its inherent rules,” he said. “What hope is there for such a person?”

He perceived those rules — not just the rules written in black ink on parchment, but the order built into creation, and his speech and conduct reflected that.

Camp Morris neighbors of the of the Rosh Yeshivah knew to avoid grilling, even on beautiful summer days. Food should be prepared in a kitchen, eaten with dignity in relative privacy.

A talmid was helping him pack his suitcase, and the Rosh Yeshivah indicated one pair of pants, and then another pair of trousers. The bochur was perplexed by the use of two different words for what appeared to be an identical item of clothing.

The Rosh Yeshivah explained: “The ‘pants’ are for weekday, but the ones that go with my kapote are ‘trousers,’ because they are worn on Shabbos.”

A bungalow colony in which several talmidim purchased homes opened a morning kollel. The organizers reasoned that some of the mechanchim and yungeleit who summer in the Catskills would benefit from the extra funds, and the increased Torah learning would benefit the colony with an extra level of spiritual protection.

One of them went to update the Rosh Yeshivah about the new kollel they were establishing.

“It’s a beautiful initiative,” the Rosh Yeshivah said, “to have a chaburah of people learning Torah together in your colony, and it is worthy of admiration. But please, do not call it a kollel. It is not a kollel. A kollel is a place in which yungeleit grow in learning under the guidance of a rebbi… and this is not that.”

One Shabbos, he noticed someone standing outside and chatting as the haftarah was being read. The Rosh Yeshivah sent for him. He did not quote halachah to him or give mussar. Instead, he asked a question: “How,” Rav Aharon wondered, “is this the hanhagah of a ben Torah during the divrei hanavi?” As if to say, The navi is speaking! Here we are, mid-prophecy — is this how those who are meant to be attuned to the call of prophet act as he speaks?

Someone gave the Rosh Yeshivah a substantial amount of money to distribute as he pleased. He wanted to give it out to the yungeleit in Kollel Gur Aryeh, the institution which was baked into his heart — and not just the yungeleit, but their wives and children as well.

The Rosh Yeshivah was discussing the planned distribution with some board members, and one of them suggested that rather than divide the money between all the yungeleit, leaving each one with a relatively insignificant amount, he should choose ten of the most choshuve yungeleit and present each one with a large gift.

The Rosh Yeshivah looked at him. “Please explain what you mean by choshuv. What makes a choshuve yungerman?” he asked.

The lay leader quickly tried to backtrack. “I’m sorry, I take back what I said.”

“But you did say it,” Rav Aharon said firmly, “so let’s discuss it. What does choshuv mean?”

It was quiet in the room. The Rosh Yeshivah named a younger member of the kollel, not considered to be one of the elite members.

“Is he on your list of the ten most choshuve members?” he asked.

The fellow did not answer, but the Rosh Yeshivah waited expectantly.

“No,” he finally said.

“But two years ago,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, “he couldn’t read a Gemara on his own, and now he’s learning Maharsha. How could you say he’s not choshuv?”

Satisfied that he had made his point to a talmid — one who, in his capacity as a board member, carried extra responsibility to understand it — the Rosh Yeshivah let the subject drop.

But as demanding as he was with his talmidim, he was even more demanding with himself.

An ad appeared in a newspaper for the Camp Morris Cheder Day Camp: featuring geshmake leagues and feste sports.

It was brought to the Rosh Yeshivah’s attention, and later that day, he saw one of the yeshivah’s younger board members.

The Rosh Yeshivah wanted to speak with him, but the board member was accompanied by his young son.

The Rosh Yeshivah asked the 12-year-old boy for a moment of privacy, telling him, “I must yell at your father for a moment.”

Then, in a private room, the Rosh Yeshivah — who did not approve of advertising a yeshivah day camp in general and especially not of “selling” a learning program based on its sports curriculum — did indeed yell at his talmid.

“The yeshivah is not yours to do with as you please,” he said. “It is a yeshivah. It’s bigger than you.”

Around half a year later, the Rosh Yeshivah called over the son of that board member. “Do you remember I once had to talk to your father, and I asked you for privacy so that I could yell at him?”

The boy nodded.

“I want you to understand that I did not actually mean to yell, but rather, to be mechanech him,” Rav Aharon told the boy.

There was one talmid who was not showing up to Shacharis. When the Rosh Yeshivah brought it up, the talmid replied that many of the rebbeim in yeshivah also davened elsewhere and he wasn’t the only one who missed Shacharis in yeshivah.

“You appear to be cross-eyed,” said the Rosh Yeshivah, covering his mouth and whispering that final word. It was clear that he was uncomfortable using a derogatory term, but felt it necessary to convey his point.

The talmid was confused. He wasn’t cross-eyed and had no idea what the Rosh Yeshivah meant.

“What does that term mean?” Rav Aharon asked, and he answered his own question. “It means a person who is looking this way, yet he sees that way. I asked you about you, and why you do not daven in yeshivah. The only person you should you be looking at is yourself, and instead, your vision takes you to another person, and you answer me based on that. But don’t you understand, that yenneh, the other person, is not part of this conversation? Don’t you understand that in the next world, when the Ribbono shel Olam is asking you questions, there will be no yenneh for you to blame it on?”

Years passed, then decades. Nearly 30 years after the incident, a talmid reminded the Rosh Yeshivah of the story, saying that it helped him understand that a person’s focus should be only on his own relationship with Hashem, without comparisons.

The Rosh Yeshivah appreciated the story and message, but he was perplexed by one detail. “Really?” he asked. “I used that word?”

The talmid clarified that even though the Rosh Yeshivah had used the term “cross-eyed,” he had first covered his mouth and he had also whispered it, as if to make it clear that it wasn’t a word that he was comfortable using.

“Ah,” the Rosh Yeshivah smiled, “that makes more sense, okay.”

But there were moments in which even the great communicator searched for the right word but couldn’t retrieve it. He was once speaking to talmidim about the tzurah — the image — of a Yid, and he paused, searching for the right term to make his point. He couldn’t come up with it, so instead, he cried out, “A Yid geit mit a bord! A Jew goes with a beard!”

Not an argument, just a statement of fact. “The Rosh Yeshivah reached our hearts that way,” said a talmid. “When he couldn’t come up with a proper word, all he had was his cry — and it was more powerful than anything.”

With Rav Yosef Eichenstein, Edison Rosh Yeshivah and a fellow talmid of Rav Hutner

One of the realms in which that air of royalty was most palpable was in the home the Rosh Yeshivah and Rebbetzin created. Together, they had five children — two sons, Rav Mordechai Zelig and Rav Nosson Tzvi, and three daughters, Rebbetzin Esther Yormark, Rebbetzin Nechama Halioua, and Rebbetzin Yehudis Senderovitz, each of whom has given themselves to this yeshivah in various capacities.

Bochurim were not just welcome, but part of the household. For decades, bochurim ate the Shabbos seudos at the Rosh Yeshivah’s table.

Later, there was a long, difficult era in which the Rebbetzin seemed to slip away, and it was during that time that the talmidim got to see new depths to the levels of respect and nobility of their rebbi.

The Rebbetzin suffered from Alzheimer’s. At first, she would still communicate, but then she stopped speaking or reacting at all, seemingly in her own world. Yet just as he always had, with the same stateliness and warmth, did the Rosh Yeshivah continue to address her: He would not leave the house without saying goodbye to her, and when he returned home, he went to greet her. He would not recite Kiddush until she was at the table, though there was no evidence of that she knew where she was, and one night, he went to a simchah of one of her relatives. It was hard for him to get out, but the Rosh Yeshivah told his daughter that he felt that perhaps it would give his wife pleasure to know that he had gone to show honor to her family.

In a situation that generally brings forth frustration and despair, he brought forth even more honor, kavod for his wife, kavod for what they had built together, and kavod for the Creator who had written the script, so clearly it was meant to be an opportunity to grow.

The home was really an extension of the beis medrash, the beis medrash he had never left.

There were times in the year in which the emotion that connects Torah and avodah came pouring out, filling the spacious beis medrash with joy, or gratitude, or connection.

On Purim, the crowd spilling over the bleachers was miraculously silent as the Rosh Yeshivah’s voice would ring out, filled with optimism, filled with love, filled with dveykus. As they sang, asking for yeshuah and rachamim, the Rosh Yeshivah’s eyes dancing up and down the rows brimmed with that love and belief in each one of them.

On Simchas Torah, they come from all over Brooklyn to see the miracle of this yeshivah, an army loyal, proud and committed, headquarters of kavod haTorah. The sifrei Torah come out into the outstretched arms, and it seems they might never be returned — but eventually, the singing ends, the last exhausted voices falling silent as the aron kodesh closes.

The erelim (the malachim) and the metzukim (the tzaddikim) both clutched the aron kodesh. The erelim triumphed and the aron kodesh was captured… (Kesubos 104a).

Now, as one last Se’u Shearim swells up from the talmidim — reverent, grateful, awed — the gates open and close and all is silent.

The angels have triumphed.

All that remains, now, is the image of the Rosh Yeshivah, his face glowing not with the light of Torah and not with the light of avodah, but with the light created when they merge into one: arms outstretched, he appears to be dancing before them, but really, he is merely showing them the way.

He, man of malchus and of true kavod, is showing them how to dance before the Melech HaKavod. —

The Final Kavod

By Ahava Ehrenpreis

I stand watching a veritable sea of black and white as talmidim, rebbeim, and roshei yeshivah move slowly behind the dark vehicle with its honor guard, members of the NYPD, and thousands of mourners walking behind their rosh yeshivah, the revered gadol Rav Aharon Schechter ztz”l.

Many decades ago, I first walked down this avenue, newly married; my husband had been davening in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin since he moved to Brooklyn, as he would until the last year of his life. Our sons attended the yeshivah from elementary school through mesivta and on to the Kollel Gur Aryeh, themselves newly married.

The relationship with the Rosh Yeshivah would be an integral part of our lives, my husband often remaining after Shabbos morning davening to speak divrei Torah with him. And when the massive edifice that would be the yeshivah’s new home was erected, my son surprised me with a seat next to the mechitzah with a view of the sea of bochurim, rebbeim, and even the Rosh Yeshivah himself. From my vantage point in the ezras nashim, I had a clear view of the Rosh Yeshivah and the seemingly endless stream of talmidim exchanging a few words and “Good Shabbos” with him after davening. Each week, I would watch the honor guard accompany the Rosh Yeshivah home after davening.

The Yamim Noraim and Yamim Tovim were the highlights of my relationship with the yeshivah. Spread out before me was a sea of white talleisim, dark suits, and black hats. I watched all eyes following the Rosh Yeshivah as he made his way up to the bimah. His voice, soft but clearly audible, called out the kolos for the piercing sounding of the shofar. The crescendo of voices calling out Shema as the closing gates of Ne’ilah surely carried our tefillos upward. Moments later, heads lifted and it was time for song, the joy as intense as the trepidation just moments before. The Rosh Yeshivah, his face glowing, turned his smiling countenance toward his talmidim, his entire being lifting the olam, encouraging them, and with each repetition, the joy rising another level as the entire kahal would sing over and over, “Yevarech es Beis Yisrael, Yevarech es Beis Aharon.”

Forever in my memory — and I’m sure I’m not alone — is Simchas Torah: the swirling circles of black and white, talleisim flying, young men soaring, encircling the Rosh Yeshivah, celebrating their learning and their leader in Torah. Culminating with the thunder of Se’u Shearim, the closing of the serious days of the Yamim Noraim and the joyous days of Succos found waves of bochurim surging in front of their beloved Rosh Yeshivah as the sun set through the towering windows of the beis medrash.

Yet that is not what I wish to share as the most meaningful aspect of this giant in Torah. Although the Rosh Yeshivah conveyed in his demeanor and shared with his talmidim the sense of majesty in their role as bnei Torah, there was a warmth and closeness evident in a charming letter that my son Akiva, as a young boy during vacation, wrote to the Rosh Yeshivah. It covers two sides of looseleaf paper in that great young boy script: “Besides my regular sedorim, I try to keep what the Rosh Yeshivah told me, one hour a day of learning with five minutes of mussar as a separate seder.” Then Akiva discusses the middah he is working on and closes the letter with a postscript, “Chas v’shalom the Rosh Yeshivah should think he is meshubad or I am expecting a letter from him but in case, my address is….” The kesher was so strong that he knew he could correspond with the Rosh Yeshivah (even during vacation).

Gadlus is not defined in words; rather it is defined by actions, in relationships. The dignity and honor of being a gadol, conveying the respect that learning Torah deserves, was, indeed, a princely endeavor he shared with every talmid, with the warmth and connection that molds the fortunate recipient.

As I stood outside the yeshivah after the levayah, it seemed that all those decades of talmidim who had joyously danced celebrating this beacon of Torah were now walking behind the aron in a final display of kavod.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 976)

Oops! We could not locate your form.