Out of Thin Air

| August 8, 2023Two pilots marvel at the Divine plan that crossed their paths in the nick of time

Photos: Itzik Belinsky, Personal archives

Nadav Efrat is the only top-tier flight instructor in Israel today who looks like a middle-aged rabbi.

But that hasn’t stopped this former Israel Airforce combat helicopter pilot from serving as head instructor at the Meggido flight school, having clocked in tens of thousands of hours flying helicopters and single and multi-engine light aircraft.

Nadav is also a long-time chozer b’teshuvah, who, after being discharged from the air force and completing a degree at the Technion, married and raised a family in the northern chareidi town of Rechasim, where he co-founded a beis medrash and kollel which he traveled to the US several times a year to fund.

And that’s how, about 15 years ago, he found himself on an El Al flight that would both close a circle and reopen memories of the most harrowing night of his life.

Right after takeoff, the captain of the jumbo jet announced: “Dear passengers, this is your captain Aharon Sagi, and I’m happy to be hosting you on El Al Flight 001 to New York….”

“Aharon Sagi — I couldn’t believe it! I stopped the closest flight attendant and asked her to tell the captain that Nadav Efrat from the air force was on board,” Nadav relates.

Sagi, former air force flyer, was clearly surprised — he hadn’t seen Nadav in 35 years — and he asked the flight attendant to escort the passenger to the cockpit. As the heavy door opened, Sagi, now a commercial pilot, had a double surprise: Instead of a 50-something military man, here was a bearded chareidi rabbi in a suit with tzitzis hanging down like a banner.

“I hadn’t seen Aharon Sagi in over three decades,” Nadav says of that encounter, which would become the first of many, “but our connection was still there. Our lives had intersected years before, culminating in a dangerous and daring nighttime rescue behind enemy lines during the 1973 Yom Kippur War.”

Yom Kippur 2023 will mark 50 years since the war that caught everyone by surprise, and surely much ink will be spilled over the next few months rehashing and analyzing the events leading up to and during those difficult days of so much pain and loss. But for Aharon (Ahrele) Sagi and Nadav Efrat, it will continue to bring back the private wonder of lives intertwined in a pattern that only becomes evident in hindsight.

Aharon Sagi, or Ahreleh to his friends, is now a retired civilian pilot with more than 33,000 flying hours under his belt. Today he’s busy with his hobby of restoring old planes, but as with many of El Al’s crew, he began his career in the Israel Air Force.

Back in 1970, Ahreleh was a 23-year-old fighter pilot, trained to operate the Air Force’s new Phantom planes. His first love, though, was flight instruction, and because he was available on Fridays, he agreed to teach flying on a single-engine Piper Cub plane at a civilian flight club in Haifa.

While most of Ahreleh’s students were at least twice his age, one day, a 17-year-old high school student by the name of Nadav Efrat showed up at the airfield.

“Ever since I was a kid, I dreamed of being a pilot,” says Reb Nadav Efrat today, “and I allowed myself to dream big. When I was growing up in Kiryat Chaim outside Haifa, we had a neighbor who became orphaned. After his army discharge, he took most of his inheritance money, purchased a Stearman plane, and then got himself a civilian pilot’s license. He used to come speak with my father, and I always heard fascinating flight stories from him. Listening to him, I knew what I wanted to be when I grew up.”

But two things got in the way, and Nadav knew he’d have to fight to make his dream come true. One was that when Nadav was a senior in high school, the draft office medical board gave him a low profile of suitability for a combat unit in the army.

“I grew up in a very patriotic environment, and the thought of having a desk job horrified me, so I did everything I could to elevate my profile,” Reb Nadav relates. “I found out that a family doctor in our neighborhood also served on the medical board in the draft office, and I had my father contact him. The doctor invited me to another medical review, and there he persuaded his colleagues to give me a grade of 97% on the profile — and that’s how I was eventually able to sit for the exam to determine if I was suited for the IAF’s flight course.

The second impediment was money.

“I felt I needed some kind of booster course beforehand, and I’d heard that in Haifa, there was a flying club at the time — it didn’t bother me that I was the youngest one there, and besides, the price was rock-bottom. But it was still more than I was able to afford.”

To make money for the lessons, Nadav dug into the savings he’d been amassing since he was a kid. He’d go around collecting old shmattehs, items his neighbors had discarded or tossed into their yards. Each week, a man on a horse-drawn wagon would pass through the neighborhood announcing “alte zachen,” and Nadav would sell the peddler his scraps for a few lirot. Copper was especially valuable and its price was established by weight.

“I saved the money I earned to pay for my flying lessons,” Reb Nadav says. “At the airfield, I was sent to a young pilot named Aharon Sagi, who had been training to fly Phantom jets at the Ramat David base, and on Fridays he taught flying at the club in Haifa. I couldn’t believe my luck. The Phantom was then the king of the Air Force, responsible for the victory over Egypt in the War of Attrition. Here was an Air Force pilot, and a Phantom pilot to boot. I literally worshipped him.

“I told Aharon that my dream was to be a pilot, and that I had even received an invitation from the Air Force to be tested for suitability for a flying course. Aharon Sagi became my advocate, the person who believed in my dreams.

“But after four lessons, the next Friday I actually came to say goodbye. I told Aharon that I had to cancel our lessons, that I couldn’t continue because I’d run out of money and had no way to pay. Ahreleh seemed pretty disappointed, too — he had been so encouraging. He kept telling me I had a lot of natural talent, but that he couldn’t give me a break even if he wanted to because he was working as a volunteer.

“Yet as I was leaving, I turned around and asked Ahreleh if he thought I had a chance at being accepted to the Air Force’s flight course, and if yes, whether I’d pass. ‘You’re a natural,’ he told me encouragingly. ‘Don’t give up your dream. Just go for it! You can definitely do it!’

“For the next two years, those encouraging words kept ringing in my ears and gave me the confidence to push forward even when I thought of throwing in the towel.”

The next year, Nadav joined the Air Force, got his “wings” in November 1972, and in the spring of 1973, he successfully completed Flight Course 69 and was placed in the first helicopter squadron T124. Less than half a year later, the Yom Kippur War broke out.

After 50 years, Ahreleh Sagi and Nadav Efrat had a reunion at the Haifa air field, flying together again in the old single-engine Piper Cub

Crash Landing

It was to be the IAF’s most difficult war. On Yom Kippur, October 6, 1973, Egyptian ground forces crossed the Suez Canal, while Egypt’s planes swooped down on IDF soldiers along the front lines. Syrian planes also pummeled IDF positions, as Syria’s artillery shelled Israeli settlements while hundreds of its tanks swarmed westward, wresting control of a large part of the Golan Heights.

During the first two days of the war, the IAF’s mission was to block the enemy’s advance. IAF jets bombed and strafed Syrian forces under heavy threat from state-of-the-art Syrian SAM missiles. On October 7th, six IAF planes were shot out of the sky by Syrian fire, although along the Suez, the heroic efforts of Israel’s pilots succeeded in seriously damaging Egypt’s SAM capability: 32 SAMs were knocked out and 11 others damaged.

Once the IDF had regrouped and begun pushing the enemy back to its own territory, IAF planes on both fronts began attacking convoys, armor, and airfields in Egypt and Syria, and picking away at the two enemies’ air forces.

In response to surface-to-surface missile attacks on Israeli civilian targets, the IAF carried out attacks deep inside enemy territory, destroying important strategic targets including oil installations, government offices, refineries, and radio relay stations. They shot down about 60 enemy planes during the war, but the toll was high: 53 Israeli airmen were killed in the fighting.

Ahreleh Sagi had been one of the veteran pilots in the squadron, and as such, was sent for especially difficult missions and dangerous sorties deep in enemy territory. Among those missions was the attack on Syrian military headquarters on the fourth day of the war, as two flying formations of Bat Squadron aircraft set out for the attack in the heart of Damascus. The seven planes penetrated into enemy territory at low altitudes, so as to avoid the anti-aircraft missile batteries deployed all around Damascus. But then they had to climb higher because the area was completely covered in clouds. Miraculously, the leader of the formation detected a hole in the cloud layer, just opposite their target, and the planes entered for strafing runs one after another. Soon Syrian headquarters became a mountain of rubble, although one pilot was killed in the attack and his navigator fell captive. Ahreleh returned safely from what he says was one of the most daring and dangerous missions that the IAF ever undertook.

Ahreleh had no chance to sit on his laurels, though. From there he moved to the southern front, against the Egyptians.

On October 20, the fifteenth day of the war, four days before the ceasefire, Aharon Sagi was ending his strafing runs in Egypt, feeling the pressure had lowered as the southern front was by this time almost missile-free.

He got into the cockpit, with veteran navigator Colonel Moshe Bartov in the seat behind him.

“We crossed the canal, when suddenly I noticed that missiles were being fired at us,” Ahreleh Sagi recounts. “I managed to evade two of the missiles, but soon realized my plane was being ambushed. And then, looking down, I spotted the battery where the missiles were being fired from and decided to aim for it and blow it up. I began a nosedive toward the battery, when suddenly over the transmitter comes an order: ‘Don’t attack! Don’t attack!’

“Apparently, there were Israeli troops in the area as well, and so I had to retreat. And then, out of the corner of my left eye, I saw it coming: A missile was about to make a direct hit on my plane. And then — ‘Boom!’ The plane went into a wild tailspin.

“There was no time to lose — we had to eject quickly or we’d be incinerated. So, this is how it ends, I thought to myself. The plane was falling fast, and we literally had a second to escape — and so we ejected, flying through the air like projectiles at the mercy of the elements. And then, suddenly, we were on the ground, our parachutes at our sides.”

It was already nighttime by the time Ahreleh picked his head up, dusted himself off, and detached from his parachute. He had no idea how far into Egyptian territory they’d fallen, but upon hearing shooting in the distance, one thing was clear: In the best case they’d be taken captive, in the worst case they’d be lynched. Looking over at his colleague, Ahreleh realized there was another problem. Bartov was barely conscious — he’d broken both arms and sustained internal injuries.

“I needed to keep him awake, so I tried to keep him engaged in conversation. I also activated the communications device on the ejection belt, called a ‘Rina,’ which sends out a distress signal. Maybe, just maybe, one of our rescue helicopters would get to us before the Egyptians would. We knew the only chance we had of being saved was an airborne rescue.”

What he never imagined was that of all the airmen in the area, the one rescue pilot who saw the IAF plane going down would be his own trainee from years before: the young fellow whose dream Ahreleh unwittingly helped come true — Nadav Efrat.

The Phantom jet was king of the Air Force, and if Ahreleh was the pilot, he too was king.

“It was just before sunset and we were patrolling the combat zone, when suddenly, we saw two missiles fired from the area and we immediately lowered our altitude,” recalls Nadav Efrat, who had just months before the war completed his training as a combat helicopter pilot. “The missiles arced higher and exploded, hitting one of our planes. We saw the Phantom crash as it plummeted to the ground.” Nadav had no idea who the fallen pilot was, who else was in the plane, or whether they were even alive, but he knew he had to attempt a rescue.

“All I knew is that we had to get to them before the Egyptians did,” says Reb Nadav. “We were able to pick up the signals of the Rina, so we headed in that direction. That’s all we had to go on.”

A helicopter, Nadav says, has the advantage that it can land anywhere quickly, but that’s also its liability. It flies close to the ground, and can get shot down by almost any weapon. Nadav was literally flying into the jaws of the enemy.

Ahreleh, for his part, was doing his best to keep Moshe Bartov awake, when suddenly he heard the roar of a chopper above him.

“I heard the noise getting closer, closer, closer,” Ahreleh remembers. “I screamed to my partner, ‘Bartov, they’re coming to rescue us — just hang on a few more minutes!’ But then suddenly, the noise became fainter. The helicopter was moving away. What was going on? Would we be left here to die? Who would tell my family what happened to me?”

Nadav’s helicopter had lost the signal.

After a few minutes that seemed like eternity, Ahreleh realized that while caring for Bartov, he must have kicked and knocked over the Rina… and there it was, toppled over in the sand. He quickly straightened it up and pulled out the antenna.

By this time, Nadav and his crew had moved quite far from the ejection site, and protocol in enemy territory once a signal is lost is to retreat. But some indescribable force propelled him forward — he refused to give up and leave the area. And seconds later, Nadav got his signal back.

No one was happier than Ahreleh, who again heard the helicopter’s roar, this time moving in, until there was a flash of light as a projector shined its beam on his waving hands.

“It was literally like in the movies,” says Ahreleh, who had seen up close the grisly side of the war over the last weeks and was no stranger to the fine line between salvation and destruction, survival and death. “Four soldiers and a medic rushed out, put Bartov on a stretcher and ran back with him into the belly of the chopper, and I followed, pulling the latch down behind me. The entire operation didn’t take more than a few seconds, and we were up in the air again, flying away from enemy territory.”

The doctor on the craft was none other than famed South African physician Syd Cohen a”h, a former Spitfire pilot who joined the South African Air Force during World War II at age 19 and fought against the Nazis. He then volunteered for the Israeli Air Force when the State of Israel was founded, creating a special unit for all the veteran pilots who arrived from abroad to help the fledgling state. A few years later he returned to South Africa to complete a medical degree, returning to Israel in 1965 where he served as a doctor at the Tel Hashomer Medical Center as well as the Chief Medical Officer for El Al. During both the Six Day War and the Yom Kippur War, he served as an airborne combat medic and laid the groundwork for the Emergency Aerial Medicine unit.

Nadav remembers how Ahreleh tried in vain to fold his parachute and get it into to the helicopter. At one point, the parachute began to inflate from the wind generated by the rotors, and with no time to lose, Nadav instructed one of the team members to grab Ahreleh and leave the parachute to the Egyptians.

Once safely ensconced in the chopper, Ahreleh could finally breathe easy, knowing he was on his way home. But the biggest surprise was yet to come.

“As soon as I got my bearings, I wanted to go and say thank-you to the brave pilots who drove the mission against the odds,” says Ahreleh. “I made my way to the cabin, stuck my head inside — and what a shock: ‘Nadav!’ I screamed, ‘is that you?!’ And he was just as shocked. ‘Sagi! It’s you!’ I don’t believe it! Ahreleh!’ Of all the possible combinations, it’s just incredible that somehow the two of us were brought together like that.”

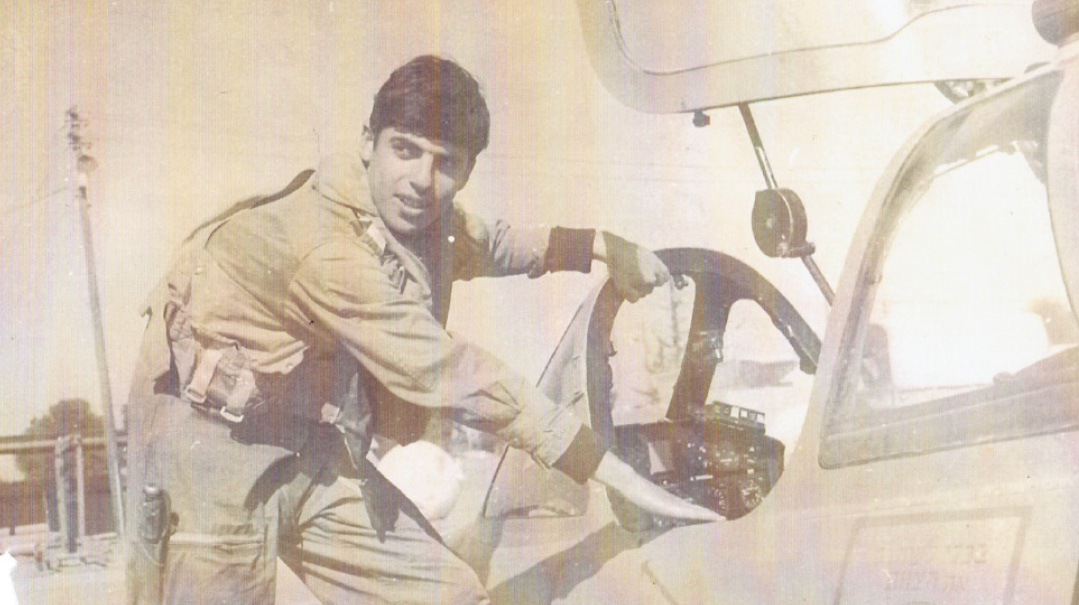

Nadav on his own first solo flight

True Patriot

Like so many other front-line fighters in the Yom Kippur War, Nadav went through his own trauma and introspection, and except for mandatory reserve duty, decided to move away from military life. He says he had a lot of close interaction with the top brass, seeing them up-close in the most tense and pressured situations, and began to realize that not only were they just regular people, they were often weak characters worried about their status and egos.

Nadav went on to study architecture in the Technion, married, had two little girls, and was living in the Haifa suburbs known as the “Krayot.” His wife had some family living in Kfar Hassidim (despite the name, it had become a regular, open-to-all town) and the Efrats decided to move there. And although they were secular, they decided to send their children to religious day-care and kindergarten.

“We wanted something with more modesty, with more Jewish content,” Reb Nadav says. “I was a very patriotic Jew in the broad sense of the word, and although I was far from religious, I wanted my children to feel connected.”

A few years later, and the girls began learning in the Bais Yaakov of the adjoining chareidi town of Rechasim.

“It was a process,” says Reb Nadav. “I can’t pinpoint one event that turned us around, although I can point to many steps along the way. My wife was a trainer for competitive women’s sports, and I once traveled with her to Germany for a competition. Now, I was a proud Jew, a patriot who’d risked my life numerous times on the battlefield for the Jewish nation, although I really didn’t understand much. So when a group of German women who were big supporters of Jews and Israel asked me questions about faith, I really didn’t have any clear answers for them. I just garbled something about a Higher Power. ‘But you’re a Jew!’ they told me. ‘What are you doing for your G-d?’”

Nadav and his wife slowly took on mitzvah observance and eventually moved to Rechasim, where he began learning Torah half a day and working half day, first as an architect and then as a construction developer.

During those years, in the 1970s and early ’80s, a wave of pilots and other military personnel somehow found their way to yeshivos. One of them was an F-16 fighter pilot and friend of Nadav by the name of Yochai Eshkol. In time, Reb Nadav and Rav Yochai would found a beis medrash and kollel, which Nadav built right under his own home.

In 1996, Nadav and Rav Yochai Eshkol made their first fundraising trip to the US for the kollel, a mission Reb Nadav would continue for the next two decades.

“I discovered three wonderful things about American Jews,” says Reb Nadav. “Their tremendous hachnasat orchim, even for those they don’t even know, the honor and importance they accord to kiruv, and the dedication working men have for non-negotiable, fixed chunks of time for learning.”

In order to keep up with his new friends across the ocean, Reb Nadav began printing a weekly parshas hashavua sheet with meaningful divrei Torah, but it wasn’t only for Jews in Brooklyn. He began sending it to his old military friends as well. And after he reconnected with Ahreleh Sagi, his former flight instructore too began receiving the weekly missive.

After completing reserve duty at age 50, Nadav, upon the advice of his rav, decided to return to flying professionally. Today he’s the only chareidi licensed flight instructor in the country.

Does his religious look put off some clients?

“Not at all,” he affirms. “Actually, I think it makes them feel secure. I always have them make the brachah shehakol on something before we take off. And when it’s time for their flight exam, I’ll tell them to donate 40 shekels to Kupat Ha’ir, because tzedakah opens pathways for Hashem’s brachah.

“I’ve seen that the best way to have an influence on others is by personal example. You don’t need to give them a headache with speeches and messages. Just be yourself and show them how it works. My clients tell me they feel safe when I’m in the plane with them, like my beard will somehowone give them Divine protection.”

Four soldiers and a medic poured out of the chopper’s belly and raced to the rescue. Nadav, for his part, refused to leave the area, even after the signal disappeared

From the time Nadav and Ahreleh “found” each other fifteen years ago on that El Al flight to New York, they’ve stayed in touch and aren’t shy about sharing their story. Reb Nadav is even helping Ahreleh Sagi, an airplane buff with a penchant for restoring early-model planes, to build a flight museum.

And nearly fifty years after that fateful rescue, they decided to make an expanded family reunion on the Haifa airfield where it all started. Reb Nadav’s family has come to join them: four daughters and a son, and sons-in-law who are all talmidei chachamim, avreichim, and roshei kollel.

As the two share their account, Ahreleh — who remembers every minute in that Egyptian desert as he saw his life pass before his eyes — is surprised that Nadav remembers all the details of the rescue as well, even after half a century.

“But there’s just one thing you’re mistaken about,” Ahreleh says as he turns to his student and savior. “I didn’t leave the parachute for the Egyptians. I managed to pack it into the chopper with me, and for many years, I had it hanging on my bedroom ceiling.”

Half a century later, Ahreleh is still learning lessons from that incredible rescue. “You know, I didn’t even know what happened to Nadav after he left my course. I gave him his first flying skills and encouraged him to follow his dream, but I had no idea he’d even joined the Air Force, or that three years later, he’d be the one to rescue me after I bailed.

“It just goes to show that you never know where a kind, supporting word — something you might not have even thought about — can go, how far it can carry the other person. It can even save a life. It’s amazing how our individual journeys become interconnected.”

Reb Nadav says that while this confluence of incidents wasn’t a factor in his becoming Torah-observant at the time, looking back, he sees how all the pieces of the puzzle are Divinely orchestrated.

“One day, Hashem knew, Ahrele would need a skilled pilot who could appear out of thin air to save his life. So I needed to become a pilot. It was Ahrele’s role to be the good shaliach who pushed me into it, who encouraged me not to look back. And then came my role: to be the good shaliach who would rescue him. We have a name for that — it’s called Hashgachah pratis.” —

Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 973)

Oops! We could not locate your form.