Warmed by his flame

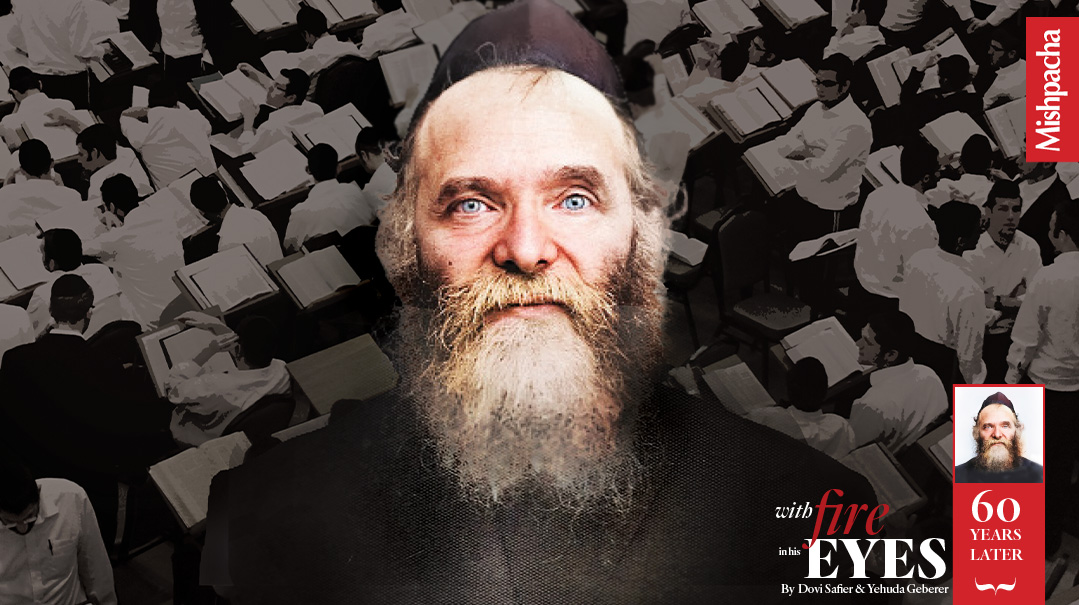

| December 20, 2022Rav Aharon’s talmidim gained a privileged close-up view to the fiery genius who became the architect of America’s postwar Torah world.

Sixty years after his passing, Rav Aharon Kotler’s talmidim across the globe serve as an informal army dedicated to safeguarding his legacy.

When a talmid speaks of Rav Aharon, his face will inevitably light up, and he’ll gaze off for a moment before returning to his audience to share a fond memory. Rav Aharon’s impact on his talmidim, and by extension, the generations that follow, is clear from just a brief encounter with any one of them.

Rav Yechiel Perr, Rosh Yeshivah of Derech Ayson in Far Rockaway, New York arrived in Lakewood in 1956. Decades later, he still remembers sitting in Rav Aharon’s shiur. “The problem wasn’t understanding the shiur,” he explained. “It was following it through all of its twists and turns.”

The shiur offered a glimpse of the sheer brilliance and breadth of “the Kletzker Rosh Yeshivah,” and many talmidim reviewed it afterward with their more learned friends in order to understand the subtle nuances they had missed as the words of brilliance overflowed from Rav Aharon in a torrent.

In addition to the actual content of the shiur, there was also the presentation: Those present in the room would watch Rav Aharon transform into a fearless warrior, defending his chiddushim while swiftly and surely deflecting any challenges sent his way.

A veteran talmid remembers the pace of the shiur; it was unlike anything he’d ever encountered. Most of the popular shiurim in the yeshivah world slowly develop a lomdishe svara, but Rav Aharon would shoot out questions on the Rishonim across the sugya and resolve them all with a brilliant solution. “Everything about it was lightning fast,” this talmid remembers.

In his battle for truth, Rav Aharon was a fierce general. A talmid once questioned a point Rav Aharon had made. In response, Rav Aharon vehemently defended his approach and rebuked the talmid, calling him “ah shikkere Turk.”

The surrounding talmidim all patted the talmid on the back, telling him, “Ashrecha, how fortunate you are to receive such a rebuke from Rav Aharon.”

(Rav Hillel Zaks, a prime talmid, later explained this colorful term as follows: A drunkard can be readily understood but is not lucid enough to have any awareness of what he is saying. A Turk, in contrast, knows what he is saying, but cannot be comprehended due to the language barrier. A “shikkere Turk” possesses both flaws: He knows not of what he speaks and is completely incomprehensible to his listeners.)

On another occasion, one of the stronger talmidim questioned a particular chiddush of Rav Aharon in the middle of shiur. The ensuing back-and-forth became heated, as the talmidim watched Rav Aharon’s face turn beet red, and he yelled at the talmid for miscomprehending his words. The talmid continued to challenge Rav Aharon, fueling his fire even more, to the point where the talmid needed to be escorted from the beis medrash.

After the shiur, Rav Aharon called the talmid in and calmly told him, “Antshuldigt — excuse me. When I say Torah there’s nothing more important in the world.”

Another talmid recalled that Rav Aharon once gave a shmuess in which he berated the talmidim for not putting seforim back in their place. There were many possible messages that Rav Aharon could have used to drive this point home, the talmid mused. There is derech eretz, there’s a bein adam l’chaveiro element as well. But Rav Aharon chose to focus on the bittul Torah likely to ensue when someone would have to spend extra time searching for a sefer that wasn’t in its proper place. “This is what mattered most to him. The Torah that could have been learned while searching for a Rambam.”

One bochur used to spend his summer bein hazmanim breaks working in a camp being mekarev young teenagers. One year, however, the camp was slated to end a few days into Elul zeman. The talmid was persuaded to stay the few extra days, given that he was involved in crucial outreach work, imbuing these young boys with a taste of Yiddishkeit.

When he returned to yeshivah, Rav Aharon called him in to his office and began to scream at him while holding open a Gemara, pointing to Rashi and Tosafos. “I don’t remember what he was showing me or exactly what he was saying,” the talmid related. “But his message was absolutely clear: He was telling me nothing was more important than Torah.”

Rav Aharon’s grandson, Rav Yaakov Eliezer Schwartzman, related that Rav Aharon was unhappy with the slow pace of study during the early days of Beth Medrash Govoha, and desired that the students cover more ground. For Shabbos, he traveled to Lakewood from his Boro Park home and spent the entire time with the bochurim. When he’d pace through the beis medrash on Shabbos, the students were wary of his disappointment with their slow progress. In order to avoid confrontation, they’d flip several pages further in the Gemara as Rav Aharon approached and pretend to engage in a discussion of the sugya further on in the masechta. After Rav Aharon passed by, they’d turn back to the earlier place in the Gemara and continue with their slow pace.

While the world saw Rav Aharon as a revolutionary leader, building Torah in a way that no one thought conceivable, and simultaneously devoting herculean efforts to major causes like the Vaad Hatzalah, Chinuch Atzmai, and Torah Umesorah, his talmidim back in Lakewood saw a different side. Perhaps not different; rather, fuller.

To Rav Aharon’s talmidim, he was not only the towering Torah giant whose eyes famously flashed the fire of Torah and whose sharp analytic prowess penetrated the walls of the beis medrash. He embodied the persona of a talmid chacham, and the refinement of his character left an indelible impression. While history notes the noticeably big accomplishments of Rav Aharon, his talmidim saw all this in the context of the smaller things.

Rav Nosson Nussbaum, a longtime maggid shiur in Ner Yisrael of Baltimore, learned under Rav Aharon for nine years. “Rav Aharon was exceedingly sharp and involved in the manhigus of Klal Yisrael,” he says, “but he was also machshiv the yachid.”

He explained that when relating to the bochurim, instead of asking them, “Vos macht du — how are you?” in the second person, Rav Aharon would ask, “Vos macht ir?” using the more respectful third-person usage. “He would even do so for 16-year-old bochurim.”

Talmidim describe Rav Aharon as very approachable. Despite his legendary passion for learning and askanus, talmidim were exceedingly comfortable discussing personal matters with Rav Aharon and consulted with him regarding shidduchim, family issues, or other seemingly small matters.

Rav Aharon once set up a talmid with a prospective shidduch. The morning following the date, as the talmid was walking into Shacharis, Rav Aharon, who was holding his tefillin and about to wrap them, gestured to him to come over. “It was amazing,” the talmid recalled. “Rav Aharon was so busy with Klal Yisrael, yet he didn’t forget that I had a date the night before, and he wanted to know how it went.”

Rabbi Nussbaum recalled the time that a bochur arrived in yeshivah from Switzerland and found that there were no beds available for rent in the area. With no other choice, he found a couch in the yeshivah and spent his first night there.

As Rav Aharon made his way to Shacharis the next morning, he noticed this bochur fast asleep on the couch. “What are you doing here?” he asked, to which the bochur responded that he couldn’t find a bed for himself.

Rav Aharon then approached the gabbai and asked why this bochur hadn’t been given a bed. The gabbai explained that there were no more beds available. Rav Ahron looked surprised. “What do you mean, no beds available? There is an extra bed in my room. He can stay with me.” (At that time, the Rebbetzin was living in Boro Park while Rav Aharon would commute back and forth to Lakewood.)

And so it was. This young boy from Switzerland found himself sharing a room with the great Rav Aharon Kotler.

Rav Aharon’s erudition in shiur will forever be remembered by his talmidim, but his erudition in bein adam l’chaveiro was equally memorable.

The talmidim would take turns driving Rav Aharon on his regular trips to New York, and he always made sure that they were well fed when they arrived. A talmid recalls that after one trip, Rav Aharon instructed his rebbetzin to prepare supper. When it was ready, the talmid found himself eating alone, as Rav Aharon remained immersed in a sefer on the couch, craving a different type of satiety.

On another occasion, Rav Aharon once noticed that one of the workers in yeshivah didn’t possess a proper winter coat and immediately saw to it that a warm coat was purchased for him.

Once a talmid offered to drive Rav Aharon on one of his regular trips. Somewhere along the way, Rav Aharon informed him that he had to turn back, as he had forgotten something at home. The driver immediately turned back.

When they reached Rav Aharon’s home, he ran into his house and informed his wife that he was leaving and would be back later. Rav Aharon then returned to the car and explained that when they had first left, he hadn’t said a proper goodbye to his wife, so he felt it necessary to turn back.

Rav Aharon’s meticulous insight into the sensitivities of others left his talmidim in awe. Whenever they approached a toll booth, Rav Aharon would instruct his driver to pull up at the booths manned by people rather than the machines, as it wasn’t kavod habriyos to show the worker that a machine could perform the same task that he could.

Back in the early years of Beth Medrash Govoha, it was common to see hitchhikers of all sorts on the side of the road. Many people would pick them up without worry, and Rav Aharon, in his kindness, would often instruct his driver to do just that.

Rav Aharon was once being driven in a car with Rav Leizer Silver when they saw two non-Jewish hitchhikers. The Rosh Yeshivah wanted to pick them up but Rav Leizer expressed his hesitations, to which Rav Aharon replied, “What is there to fear? We are three, they are only two!”

Rav Chaim Yehoshua Hoberman, current rosh yeshivah of Long Beach, related a similar episode that was shared by his father-in-law, Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock, who held the position before him. Rav Yitzchok once accompanied Rav Aharon back from a meeting in Philadelphia, and as their car sped along, they noticed two teens looking for a hitch near the bridge.

“Did you see there were two boys on the side of the road looking for a lift?” Rav Aharon admonished.

“I don’t pick up hitchhikers,” the driver said. “They can hurt you.”

“But they’re only kids — yungitchkes,” Rav Aharon insisted.

“Still, yungitchkes can also hurt you.”

Rav Aaron was not satisfied. “Di Mama vet zorgen oif zei — their mother will be worried about them.”

And so, Rav Aharon kept at it. Six miles past the bridge, the driver asked Rav Aharon, “What does the Rosh Yeshivah want, that I should go back and pick them up?”

“Do you have a better idea?” he responded.

Sure enough, they turned back, and yes, the two non-Jewish boys were still there.

And so, Rav Feigelstock joined the Rosh Yeshivah in the back seat, the two kids squeezed into the front with the driver, and the gadol hador accompanied the two boys home so a mother somewhere in New Jersey wouldn’t worry needlessly about her children.

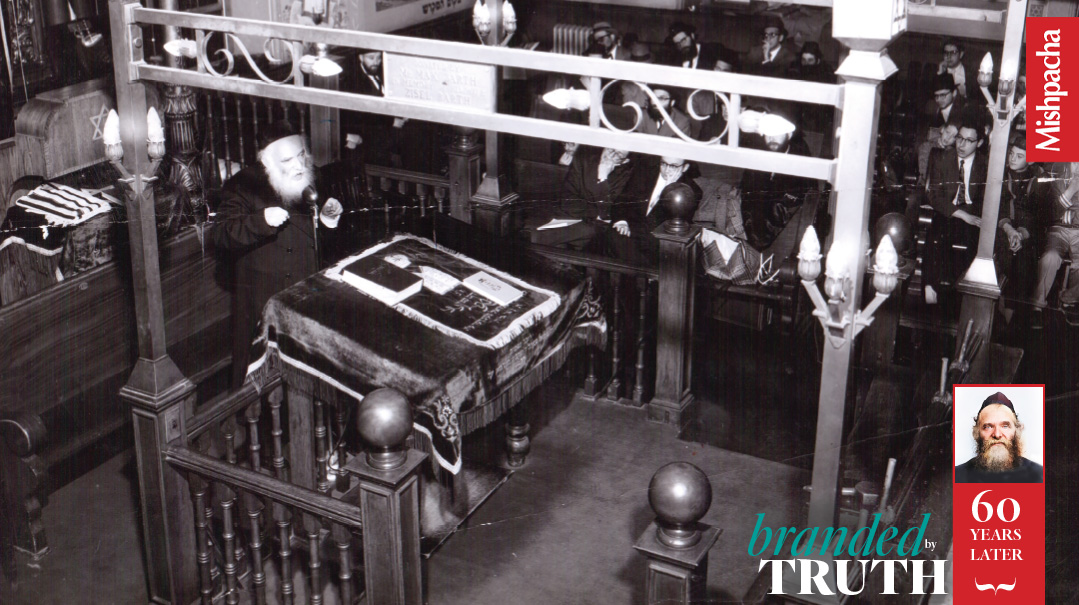

Rav Aharon spent the week dealing with global issues facing the Jewish people. But on Shabbos he belonged entirely to yeshivah. Decades later, his mark is still evident on the yeshivah that blazed a new path for Torah in America

The late Rav Shmaryahu Shulman ztz”l learned in Lakewood for a short time toward the end of World War II. He remembered Rav Aharon from those days: He spent the entire week dealing with the Vaad Hatzalah, marshalling every bit of strength to rescue and aid Holocaust refugees. By the time he arrived in Lakewood before Shabbos, he was drained of all strength. However, within minutes he would sit down to learn and appeared as an entirely different person, with a verve that had been non-existent just moments before.

Rav Aharon took on a fatherly role toward his talmidim as well. During the Shabbos seudos, he regaled his talmidim with divrei Torah and stories of gedolei Yisrael. Rav Aharon was meticulous in relating the particular details of each story, so much so that it seemed as though he was present when it occurred, identifying details such as the names of train stations and other geographic specifics.

“When describing how the Beis Halevi went out in Shabbos clothing to greet the Malbim whose train was passing through town, Rav Aharon described the exact route the Malbim took — even which stops he passed on the way,” Rav Shulman fondly recalled.

Rav Yechiel Perr also remembers those Shabbos seudos. Throughout the seudos, he recalls, the bochurim sitting around Rav Aharon would fire questions in learning toward their exalted rebbi. The mix of talmidim, however, meant that the questions dealt with different masechtos. Some were from Kodshim, some from Moed, some from the yeshivishe masechtos, and some were halachic questions. Rav Aharon sat there fielding all the questions from all areas of Shas with aplomb, which only served to increase his talmidim’s admiration.

I asked a talmid to pinpoint which was the greater lesson to be learned from his rebbi: was it the fire of Torah that he breathed or was it his middos and erlichkeit, the brand of aristocracy unique to a person wholly elevated through Torah?

He looked down and smiled, pondering for a moment. “It’s not a fair question,” he responded. “It was all of that together.”

The research of Rabbi Eliyahu Beane was utilized in the preparation of this article.

(Originally featured in Torchbearer, Rav Aharon Kotler Tribute, Issue 941)

Oops! We could not locate your form.