Embers of Eternity

Even though six decades have passed, the brilliant shiurim and ma’amarim of Rav Aharon are speaking to a new generation

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

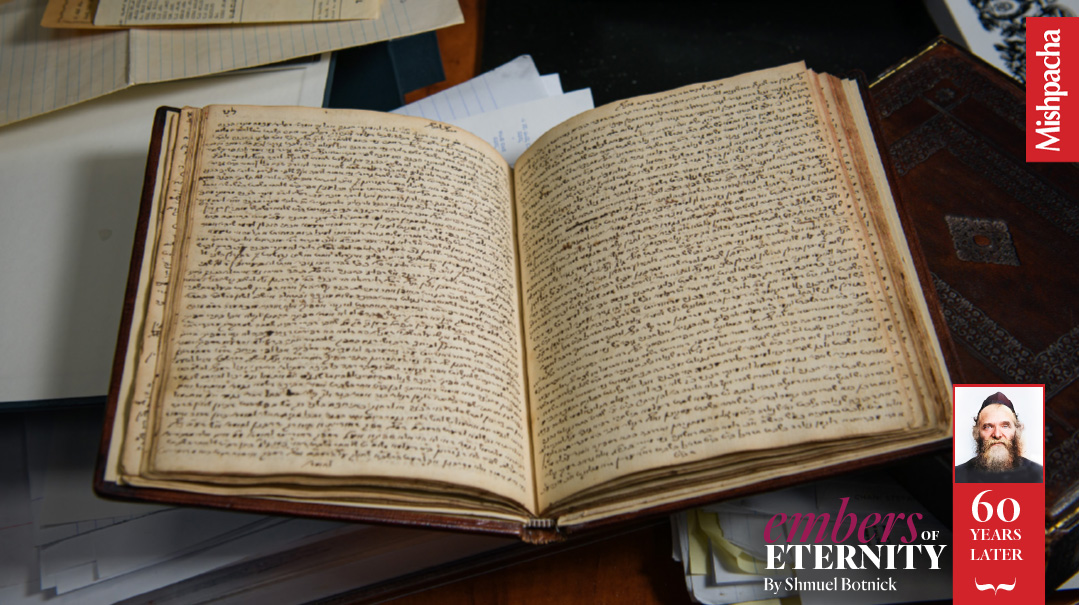

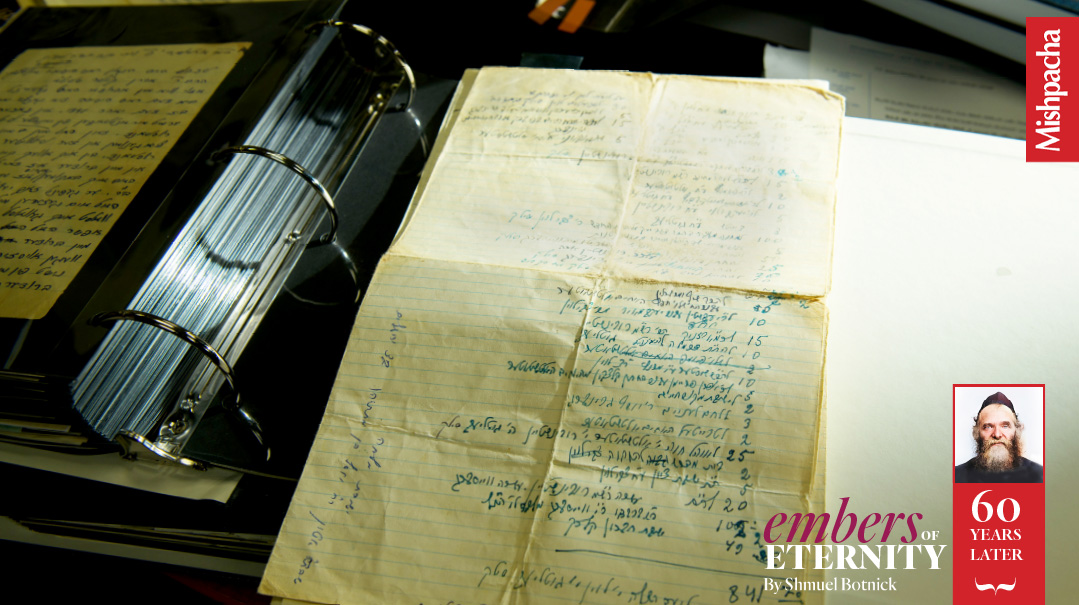

In a building in Lakewood, encased in sheet protectors, lies a treasure: myriad yellowing papers lined with the tight handwriting of Rav Aharon Kotler.

Rabbi Tzvi Rotberg has spent the past few decades working through these invaluable manuscripts, decoding, deciphering, and ultimately disseminating Rav Aharon Kotler’s timeless chiddushei Torah, intent on keeping his promise to his rebbi, Rav Shneur Kotler. His dedication to this mission has resulted in an incalculable contribution to the Torah world.

Even though six decades have passed, the brilliant shiurim and ma’amarim of Rav Aharon are speaking to a new generation

F

orest and Carey. It’s an all too familiar intersection, home to two of Beth Medrash Govoha’s batei medrash. It’s been some ten years since I last paid a visit to this campus, as one of the Yeshivah’s many talmidim. Now, as I tiptoe between the hundreds of cars jammed into unmarked parking spots, I’m hit with an unexpected jab of guilt-laced nostalgia.

As an outsider, you can’t miss it. The heartbeat, low and steady, providing sustenance while seeking no acclaim; from behind the plain, brown brick you can feel the heartbeat. I’d learned here as a bochur, but caught in the whirlwind of shidduchim, riding the roller-coaster of anxiety, excitement, disappointment, and then anxiety all over again, I’d been oblivious.

Now, as a visitor, I hear it — the majesty, the rhythm as true as the universe’s existence — and I feel a pang that I never noticed it before.

But I don’t have much time to dwell on the guilt; I’m here today with a mission. Somewhere, I’m told, positioned between the two batei medrash, is a stand-alone building that houses the Machon Mishnas Rav Aharon, an institute charged with the task of publishing the works of the previous roshei yeshivah of Beth Medrash Govoha.

I spot the small building, so humble you can easily gaze right past it, and head on over, anticipating my meeting with Rabbi Tzvi Rotberg, the director of the Machon. But as I climb the steps and approach the nondescript door, I realize that something is pulsing in my ears.

It’s that heartbeat. Again. And it has only grown louder.

“I Just Work Here”

I’ve never met Rabbi Rotberg before, but based on our phone conversations, it’s an easy guess. Right down the hallway stands an elderly man in a vest holding a broomstick. A much younger man is trying to convince him not to sweep whatever mess is on the floor, but he won’t hear of it. “When you run a machon,” he explains with a twinkle in his eye, “you have to be geshikt. You have to know how to do everything, even sweep the floors.”

It’s the perfect introduction. “Don’t mention me in the article,” he tells me multiple times. “I’m nothing, I just work here.” At one point, he explains that “I’m from a different generation. We don’t look for kavod.”

He continues sweeping until the floor is clean, and only then does he lead me into his office, which looks more like a miniature beis medrash. Newly printed seforim, all with the Machon Mishnas Rav Aharon - Mahaduras Friedman symbol on their binding, line the shelves. Rabbi Rotberg’s desk is lined with seforim as well, but a closer look reveals the most beautiful amalgamation of new and very, very old.

Peeking out from the seforim are bits of the yellowest paper, encased in sheet protectors, with tightly packed letters, identifiably Lashon Kodesh but hardly legible, scrawled from margin to margin. These papers are the core of the Machon’s existence, and the focus of Rabbi Rotberg’s mission for over 40 years.

“You will publish my father’s Torah,” Rav Shneur Kotler told a young Rabbi Tzvi Rotberg. With Rav Shneur deathly ill, Rabbi Rotberg jumped into action and released the first sefer, just two days before Rav Shneur was taken to the heavenly yeshivah. Decades later, the mission is as consuming as ever

Sacred Promise

While baseball cards may have been all the rage in the mid-20th century, 13-year-old Tzvi Rotberg cared little about the Dodgers or the Yankees, and would have easily traded a Babe Ruth for what he considered far more valuable. “I was collecting seforim since my bar mitzvah,” he tells me. He loved seforim and had a keen eye for detecting the various styles in which they were written. As he grew older, seforim and writing would become a joint passion which, as destiny would have it, would then become his life’s calling.

When Tzvi began yeshivah in Bensonhurst-based Beis HaTalmud, he met a bochur around his age named Malkiel Kotler. The two became close friends, and Tzvi was soon invited to the Kotler home for Shabbos. It was there that he was introduced to his friend’s father, Rav Shneur Kotler ztz”l.

Rav Shneur took a strong liking to Tzvi and loved to test his knowledge of seforim. “Rav Shneur would throw out a line from the Kuzari or the Moreh Nevuchim and say, ‘Nu, which sefer is this from?’ I didn’t always know the answer,” Rabbi Rotberg concludes humbly.

By the time he left Beis HaTalmud, Tzvi Rotberg was like family with the Kotlers: a close friend of the sons, and like a child to Rav Shneur and Rebbetzin Rishel. After learning in Eretz Yisrael for two years, Tzvi returned to Lakewood where he joined Beth Medrash Govoha. It was here that his relationship with Rav Shneur took on a professional dimension.

“Rav Shneur was the most incredible writer,” says Rabbi Rotberg, “and his ability to express himself was second to none.” Rav Shneur appreciated Tzvi’s writing capabilities as well, and before sending anything to be published, he would ask his young talmid to review it and provide feedback. “He trusted me, I don’t know why,” Rabbi Rotberg says.

But Rav Shneur didn’t just ask for feedback, he provided it as well. “After delivering a shmuess in the yeshivah, Rav Shneur would sometimes ask me to write it up. When I would show it to him for approval, he would compliment me, but also always offered advice on how to make it stronger or more effective.”

And in an impressive display of trust, every now and then, Rav Shneur would ask Tzvi to review one of his father’s manuscripts, in the hope that one day it would be ready for publication.

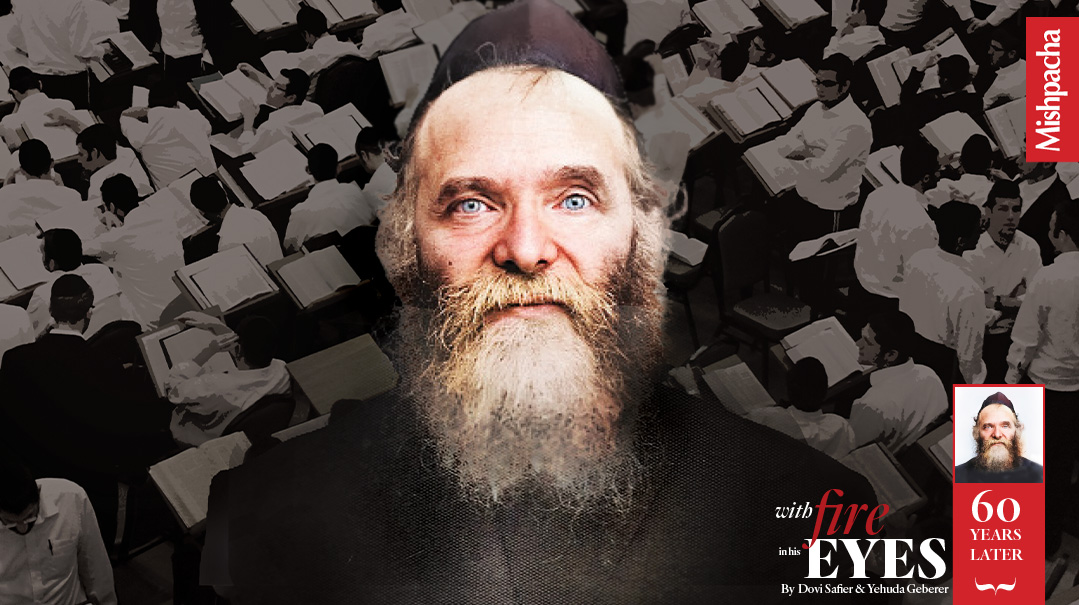

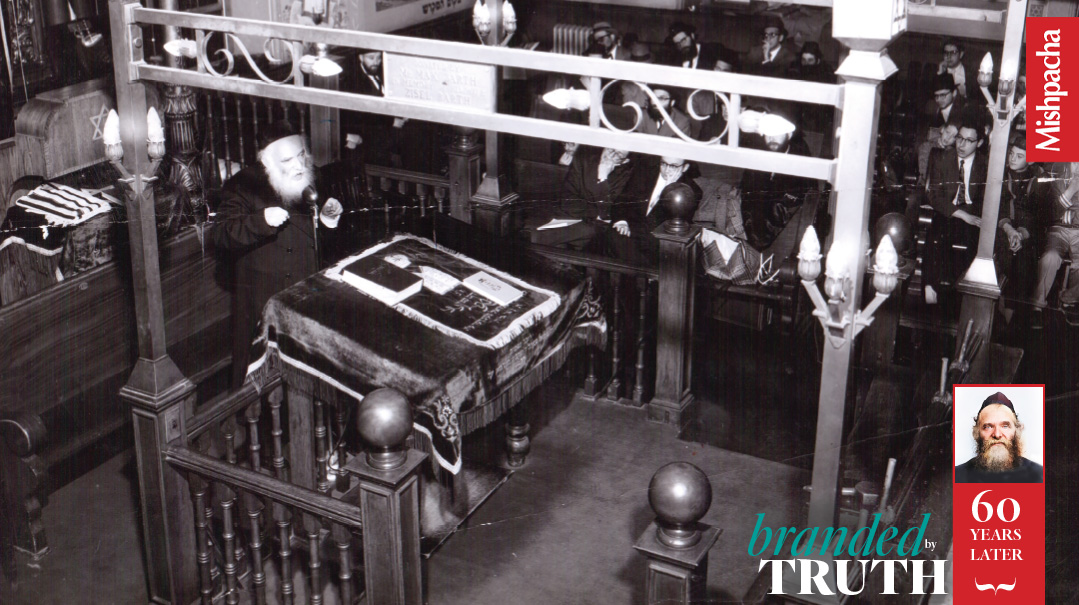

The dissemination of the Torah of his venerated father, Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l, was a lifetime aspiration of Rav Shneur’s. Rav Aharon had passed away a few decades prior and, with his passing, the yeshivah world was left bereft of one of its most brilliant minds. Hope lay in the writings of Rav Aharon, where he had inscribed his Torah for all of time. Yet who would be trusted to publish his works?

For 12 years, Reb Tzvi studied in BMG under Rav Shneur, visiting him in his office practically every day. And then the news broke. Rav Shneur was sick, very sick, diagnosed with an advanced stage of cancer.

“That Erev Shabbos he called me into his office,” Rabbi Rotberg remembers, “and he told me that he had taken it upon himself to work on having his father’s seforim published. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll help you, I’ll be there for you.’ From then on, I went to visit him every day and he kept reminding me about his kabbalah. ‘You will publish my father’s Torah,’ he would tell me, and I’d respond, ‘Me? The Rosh Yeshivah will do it!’ ”

But one day, when Rabbi Rotberg went to Rav Shneur for his routine visit, the conversation took a different course. “Rav Shneur told me, as usual, that I should be the one to publish Rav Aharon’s Torah. I tried to tell him that he would still merit to do it but he became very serious. He said, ‘I won’t. You will do it and I want you to make a kinyan to formally accept the responsibility of publishing my father’s Torah.’ ”

Rav Shneur wanted to use his fountain pen as the item with which to perform the kinyan. But the pen was missing, so they used a bottle of ink. Rabbi Rotberg had now officially undertaken the responsibility of disseminating the timeless chiddushei Torah of Rav Aharon Kotler.

“After I was mekabel kinyan, Rav Shneur called Rebbetzin Rishel into the office. He said, ‘Rebbetzin, give Tzvi all the kesavim.’ Shortly thereafter, Rav Shneur left to Boston for treatment.

“I wanted to complete a full sefer while Rav Shneur was still alive,” says Rabbi Rotberg. “At the time, I had already been given a sampling of Rav Aharon’s ma’amarim and had begun working to put them together as a comprehensive sefer. When I realized that Rav Shneur might not have much time left, I worked like crazy to get it done. I was ready to write up a hakdamah for the sefer myself and told Rav Shneur of my intentions. He was deathly ill, but he wouldn’t hear of it. This was his father’s Torah and he would write the hakdamah.”

On his deathbed, Rav Shneur dictated word for word what he wanted written as a hakdamah to the first published sefer of his father’s Torah. Rabbi Rotberg made the frantic finishing touches and, at last, the sefer was published.

Two days later, Rav Shneur was niftar.

Spreading the Light

Shortly after the shivah, Rebbetzin Rishel called Rabbi Rotberg over. “Rebbetzin, give Tzvi all the kesavim” had been one of her husband’s final directives; it was now time to fulfill his instructions.

The Rebbetzin gave Rabbi Rotberg close to 80 notebooks containing Rav Aharon’s shiurim and ma’amarim. The responsibility to spread Rav Aharon Kotler’s Torah to Klal Yisrael now rested squarely on Rabbi Tzvi Rotberg’s shoulders.

Rabbi Rotberg now had enough material to work on for his entire lifetime — and then some. But, as he’d soon discover, the project was far from simple. Upon examining the notebooks with Rav Aharon’s ma’amarim, Rabbi Rotberg noticed how on the last page of the final notebook, there was a cryptic series of references. Pinkas yud-ches… daf 32… pinkas yud-beis… daf 2…

After some time, Rabbi Rotberg understood. In his sheer genius, Rav Aharon had memorized exactly what was written in each notebook, down to the page number. The enigmatic lines were really an index, indicating that if the material from the 32nd page of the 18th notebook was connected with the 27th page of the 12th notebook, the combined content would form a full ma’amar.

Once he understood this, Rabbi Rotberg and a loyal team of employees were able to put together a catalog outlining which pages of the various notebooks were needed to string together a comprehensive ma’amar. Once the catalog was in place, he set out putting together, and ultimately publishing, the ma’amarim.

The set of ma’amarim come in four volumes. The first volume focuses on a series of topics central to Yiddishkeit, such as Emunah, Torah, Tefillah, Yirah, Chesed, and so on. The second volume contains shmuessen about the Yamim Noraim, beginning with Elul and continuing up until Succos. The third is culled from derashos that Rav Aharon gave at dinners or other events. And the fourth volume is unique in that it actually is not based upon Rav Aharon’s writings; rather, it’s taken from recordings of speeches he delivered at the multiple venues where he was a guest speaker.

Rabbi Rotberg worked diligently on these ma’amarim, deciphering the writing and putting together the many scattered pieces, but he didn’t add or subtract anything. “We never deviated from Rav Aharon’s words,” Rabbi Rotberg states emphatically. “Even when it’s very unclear. There was a time when I contemplated adding words to clarify his intention. But I came to the conclusion, together with Rav Yehudah Jacobs ztz”l, that we would absolutely not do it.”

Such was the line of order for the ma’marim, but when it came to the shiurim, things got even trickier. Rav Aharon dedicated his life to these shiurim, and they are masterpieces of almost unparalleled genius. Although their focus is on the masechtos studied in the yeshivah — Bava Metziah, Kesubos, Gittin, and the like — one of Rav Aharon’s trademarks was his ability to string together concepts from all of Shas, demonstrating how all are intertwined, perfectly consistent, woven together by a thread that couldn’t be anything other than Divine.

Since Rav Aharon’s mind worked at a feverish pace, deciphering his thought process proved difficult. “The various shticklach Torah in these notebooks have no understandable structure. One page can have a piece on Kiddushin, the next a piece on Bava Basra,” Rabbi Rotberg explains. At first, he couldn’t make sense of what was going on, but after some time, he figured it out.

“These notebooks date back to when Rav Aharon was still a bochur in Slabodka. Then there are some from when he was a rosh yeshivah in Kletzk. Rav Aharon was constantly being mechadesh more Torah, adding hosafos to his prior shiurim. When he had a hosafah on a shiur in Bava Basra, he would scrawl it into a notebook, not necessarily designated for Bava Basra. He would make a little notation, scribbling the word ‘hosafah.’ The same for Kiddushin, the same for Kesubos.”

The result was dozens of notebooks, jammed with additions to shiurim, but no clear indication as to which shiurim they belonged to. In order to put together a full shiur, complete with all its hosafos, Rabbi Rotberg had to navigate the tens of notebooks, piecing together a brilliantly complex puzzle. “It took me two years to create an index that connects the primary shiur to all the subsequent hosafos.”

Rabbi Rotberg lined up a team of prestigious talmidei chachamim to work on anthologizing the shiurim. Rav Shmuel Deutsch, Rav Efraim Zureivin, Rav Yitzchok Weinstein, and Rav Menachem Tenenbaum were tasked with the holy — and very challenging — mission. “Rav Aharon’s writings can be cryptic,” Rabbi Rotberg explains. “Sometimes, he’ll write, ‘kamevuar b’Rambam,’ but it’s entirely unclear which Rambam he’s referring to. It takes great geonim to be able to unravel these mysteries.”

Another difficulty was the hosafos. Since they were scattered throughout the notebooks, part of the job was to decrypt which hosafah corresponded to which shiur. When a question or challenge would arise, Rabbi Rotberg would turn to Rav Shmuel Auerbach and Rav Yitzchak Dzimitrovsky z”l for guidance.

Deciphering the notebooks would be a challenge but, as Rabbi Rotberg would later discover, it was just the beginning.

Rav Aharon left boxes upon boxes of shiurim, maamarim, notebooks, and correspondence. It took years to piece together the additions to long-ago shiurim referenced in his cryptic shorthand

Theft!

For some time, Rabbi Rotberg had known that there were boxes in the Kotler basement containing writings of Rav Aharon and Rav Shneur. “We knew about it, but we thought they were just tzetlach — notes.”

But at some point, Rabbi Rotberg decided to open the boxes and examine their contents. He couldn’t believe what he saw. There were, in fact, flurries of tzetlach, little notes of correspondence between Rav Aharon and his talmidim, parents of talmidim, and rabbanim from around the world. But there was also a small fortune of chiddushei Torah.

A closer look at the dozens of small leaflets lining the boxes revealed brilliant insights covering the gamut of Shas and well beyond. Further examination clarified that many of these shticklach Torah were additional hosafos to the shiurim in the notebooks Rabbi Rotberg had seen earlier. Now, the task of stringing together a complete shiur would entail yet another layer of complexity. The scrawled ideas held vital pieces of the intricate tapestries Rav Aharon envisioned, and these notes would now have to be reviewed, their content understood, and the mystery of their message resolved.

Rabbi Rotberg revealed to the Rebbetzin what he’d discovered and, as if reading his mind, she said, “I’m not giving it to you.” She explained, “I have to take achrayus over these. I will let you take five or six papers at a time, copy them, and then bring them back. But I’m not giving you the whole thing.”

For a while, Rabbi Rotberg kept taking one small, precious batch of notes at a time, and would return them once they were copied. Then, one day, Rabbi Rotberg learned that the Rebbetzin would be traveling to Eretz Yisrael. He asked her to give him the code to the lock of her front door, so he could continue taking the papers. Trusting Rabbi Rotberg, she gave him the combination.

But her trust was somewhat misplaced. The next day, he showed up at the house with his van, loaded all the boxes onto it, and drove away. Shortly after the Rebbetzin’s return home, Rabbi Rotberg knocked on the door. “Rebbetzin,” he said grimly, “siz gevehn a geneiva in shtub, there was a burglary in your home.”

The Rebbetzin took in his uncharacteristically somber expression and the glint in his eye, and she understood. “Ah, Tzvi,” she said, “ah bracha oif aihere kuhp, a blessing on your head. I couldn’t bring myself to part with them. Baruch Hashem you did it yourself.”

Between the notebooks entrusted to him and the boxes retrieved, Rabbi Rotberg is now the guardian of a virtual goldmine of Torah. And he treats it as such. Each page has been reverently placed in a Mylar archival sleeve. The gleaming plastic seems almost like a window, a vista into a mountainous neshamah condensed into tightly compacted letters with ayins swirling into lameds and tuvs dipping beneath the lines, only to reappear as a reish.

Rav Aharon’s words still live. Rabbi Rotberg and the talmidei chachamim at his Machon touch history every day, gaining a rare window into the thoughts, travels, and interactions of America’s Torah general

Reverse Engineering

As he analyzed, categorized, and deciphered Rav Aharon’s writings, Rabbi Rotberg gained new appreciation of the entire Kotler family.

“As I was reviewing Rav Aharon’s notebooks,” he shares, “I came across a particular shiur in Maseches Gittin. Something about it struck me as wrong. And then I realized I’d seen it before! It’s in the sefer Even Ha’Ezel written by Rav Aharon’s father-in-law, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer!”

Puzzled, Rabbi Rotberg tried to figure out how the identical piece of Torah showed up in both Torah giants’ work, and after some time and reverse engineering, Rabbi Rotberg believes he has solved the mystery.

The story appears to have happened as follows: Rebbetzin Chana Perel Kotler, Rav Aharon’s wife, was no stranger to greatness. Her parents were Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer and Rebbetzin Baila Hinda, and they taught her well. As her mother’s daughter, they shared much by way of scholarship and piety, and they also shared an identical penmanship. And there lay the source of the confusion.

Because although Rav Isser Zalman authored the Even Ha’Ezel, it was his rebbetzin’s notes that were sent to the printing press. She had a clearer handwriting than he did, and so she rewrote everything he had written, and the sefer was published using her notes.

During this time, the Meltzers lived in Eretz Yisrael while the Kotlers lived in New York, and Rebbetzin Kotler would often communicate with her parents by mail. Wanting to share Rav Aharon’s constant, meteoric ascension in Torah with her parents, she would send a shiur of his along with her letters. Rav Aharon would choose a select shiur and she would rewrite it, sending it along as a nachas report of sorts. That is how a shiur, written in identical handwriting to Rebbetzin Baila Hinda’s, sat somewhere among the records of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer. It looked precisely the way Rav Isser Zalman’s notes looked, since his wife had usually rewritten his notes for him.

After Rav Isser Zalman was niftar, the shiur was found. Naturally, it was assumed to be Rav Isser Zalman’s Torah, and it was printed in the next volume of Even Ha’Ezel. But it in fact stemmed from Rav Aharon.

How did Rabbi Rotberg determine this?

“Because of the hosafos!” he exclaims triumphantly. “Since I have all the notebooks,” he explains in a Gemara sing-song tone, “I was able to see how Rav Aharon was constantly adding on to that very same shiur. Now, how and why would Rav Aharon write a hosafah on Rav Isser Zalman’s shiur? So it must have been Rav Aharon’s!”

Interestingly, the letters to her parents weren’t the only time when Rebbetzin Chana Perel would rewrite Rav Aharon’s Torah. Back when they lived in Kletzk, Rav Aharon traveled to America on a fundraising trip in 1935, and took his precious notebooks with him. The Rebbetzin, afraid that the notebooks would get lost somewhere along the way, decided to create a backup and rewrote them in her own handwriting. For this reason, many of Rav Aharon’s shiurim can be found written in his wife’s handwriting. For each shiur that was rewritten, Rav Aharon would mark the original version with the word “ne’etak” (copied).

The vast number of notebooks reveal how much importance Rav Aharon attributed to writing chiddushei Torah. “I have the shiurim he wrote in Kletzk and the shiurim he wrote in America,” Rabbi Rotberg says. “But even those that were written in Kletzk were rewritten in later years. Rav Aharon felt that by writing one gains more clarity, so he was constantly writing and rewriting.”

The papers contained in those boxes extend well beyond shiurim and ma’amarim. There were letters from rabbanim all over America, letters from parents of his talmidim, and notations written on small cards; all of this was kept for posterity, first in the Kotlers’ basement and now in Rabbi Rotberg’s trusted hands.

There is one assortment of documents which, when strung together, tell an almost chilling tale of Rav Aharon’s scrupulous discipline in dealing with other people’s money. It starts with a large piece of paper containing a list of names and numbers. At the end, there is a sum total of the amount of money, followed by another number with the word “lirot” scrawled next to it.

Rabbi Rotberg explains the background. “Rav Aharon was traveling to Eretz Yisrael, and people gave him money as shliach mitzvah gelt. Upon receiving the money, Rav Aharon wrote down their names and the precise amount given. Then, when he arrived in Eretz Yisrael, he exchanged the dollars for lirot — the currency in Eretz Yisrael at the time — hence the revised number aside the word lirot. Then, whenever Rav Aharon would give a donation, he would keep an account of whose money was being given to whom.”

“Sharabani,” the document reads, “5 lirot me’ha’achim Altshtadter.” Meaning, a fellow by the last name of Sharabani received 5 lirot from the dollar amount entrusted to Rav Aharon by the Altshtadter brothers.

And so on. Every single donation was diligently recorded, tracking how much was given, who it was given to, and from which account the money was taken.

But to make matters more incredible, Rav Aharon asked each recipient to issue a receipt attesting to the fact that he did indeed receive that amount of money from Rav Aharon. “Go through these receipts,” Rabbi Rotberg says, handing over a collection of small notes.

Sure enough, the receipt reads, “Kibalti meiha’Gaon Rav Aharon Kotler al cheshbon haAchim Alshtadter ….”

There are tens of such receipts and each one matches precisely the numbers listed on the document.

Scrupulous discipline. On his trips to Eretz Yisrael, Rav Aharon would keep meticulous ledgers detailing the tzedakah he distributed, including exact numbers and names – and the receipts in his records match up precisely to the donations

His Father’s Son

“If you write about the Machon,” Rabbi Rotberg told me in our initial conversation, “then you have to write about Rav Aharon. And if you write about Rav Aharon, you have to write about Rav Shneur.”

Rav Shneur Kotler succeeded his father in leading Beis Medrash Govoha; the plethora of papers cluttering Rabi Rotberg’s desk tell chapters in his life as well. “I was entrusted with Rav Shneur’s writings as well. Over the years, we published 13 seforim of Rav Shneur’s Torah, on several masechtos in Seder Kodshim, and more recently Gittin, compiled in a series of volumes called Siach Arev.”

Through the tireless work of Machon Mishnas Rav Aharon, the brilliant chiddushim of Rav Shneur Kotler now line the shelves of yeshivos and kollelim the world over.

The boxes found in the Kotler basement also contained many of Rav Shneur’s letters, dating back to the years he spent in Eretz Yisrael. (Rav Shneur’s letters were mingled together with his father’s but easily identified by his handwriting.) Even at that young age, the letters reveal that he was very active in his father’s Holocaust rescue efforts, trying to help Jews escape Europe.

And yet another cache of papers reveals a fascinating, albeit lesser known, side of Rav Shneur. “Rav Shneur was an incredible poet,” Rabbi Rotberg tells me. “He saw the world through a poetic lens.”

He reaches for a thin pamphlet and opens it. “I published the poems — just for the family.” He points to a poem written about the Churban, composed one Tishah B’Av night. It’s written in very advanced Lashon Hakodesh, making it difficult for me to understand. Little snippets of it, loosely translated, read something like this: That blue sky was spread out on that night as well… And those stars were sparkling… They heard the destruction… And absorbed the smoke…

Another poem was written in Port Authority, describing how he sees thousands of people, running all around him, and yet he feels lonely.

But the poetry doesn’t surprise Rabbi Rotberg, who knew Rav Shneur since he was a young teenager. “Every word Rav Shneur spoke, every line that he wrote, was laden with meaning. He was always referencing a midrash, a pasuk in Nach, a quote from the Rambam.”

With time, the Machon expanded, and Rabbi Rotberg’s team began to work on other manuscripts as well, in addition to the works of Rav Aharon and Rav Shneur. “We have over 60 yungeleit working for us at the Machon,” Rabbi Rotberg says proudly. “We pay by the hour, and some yungeleit put in eight-hour days, bringing home impressive paychecks. And all this is to work on manuscripts of Gedolei Acharonim and spread more Torah.”

Rabbi Rotberg provides the yungeleit with the necessary training to decipher the very archaic writing and oversees all their work — and the resulting list of seforim published by the Machon is extensive. A very limited set of examples includes volumes of the Yam Shel Shlomo, republished with beautiful print and hundreds of footnotes that clarify each of the many maamarei mekomos cited throughout the sefer; a two-volume set of Ner Mitzvah, a commentary on the Rambam’s Sefer Hamitzvos written by Rav Yehudah Sid, Rav of Bulgaria in the early 19th century; and the sefer Imrei Binah by Rav Meir Auerbach, who served as the Rav of Yerushalayim following the passing of Rav Yehoshua Leib Diskin.

Rabbi Rotberg’s enthusiastic description of the Machon’s work begs a question. “Where is all the money coming from?” I ask.

Rabbi Rotberg’s voice takes on a heavy tone. “It used to be that I was raising every penny of it. Going from door to door, collecting donations to the tune of ten to eighteen dollars.”

But Hashem smiled on his efforts and, perhaps in the merits of Rav Aharon and Rav Shneur, salvation came by way of famed philanthropist Reb Hershey Friedman and his wife Raizy of Montreal, Canada. “I don’t know why,” Rabbi Rotberg humbly admits, “but Reb Hershey wanted to take on the Machon. He gives a very large portion of the funds we need. I still have to collect some but he’s made the job much, much easier.”

The Machon was renamed “Machon Mishnas Rav Aharon Mahaduras Friedman” in tribute to their generosity, and with the funding now available, the Machon is publishing an average of a sefer a month, having recently put out their 220th sefer. The building they are currently housed in is being renovated to allow for more working space and a larger beis hamedrash.

“So, what are your plans moving forward?” I ask. “Do you have any specific vision for the future?”

The man who spent 40 years dedicated to spreading the Torah of his rebbeim raises his voice an octave.

“We’re not gonna sleep,” he declares. “We’re constantly evolving.”

There’s something about being in the presence of Rav Aharon Kotler’s original writings that makes it hard to say goodbye. But after spending over an hour poring over the manuscripts, it’s time to be on my way. I head out the door and begin climbing down the steps, and suddenly, I hear it again.

The heartbeat. Constant, steady, the background harmony to the thousands of voices echoing from the two batei medrash that I stand between.

I shake my head. Whose is it? Where’s it coming from?

I think back to those manuscripts, the electric current running through the rapid writing, the sense of purpose and dedication pulsating through every word, and I know.

He left us 60 years ago, but somewhere up in Shamayim, Rav Aharon’s heart continues to beat.

(Originally featured in Torchbearer, Rav Aharon Kotler Tribute, Issue 941)

Oops! We could not locate your form.