Silent to Safeguard

| December 6, 2022Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov’s secret plan to bolster American Jewry

Photos: Mishpacha archives

Instead of merely lamenting the fallen spiritual level of his brethren in America at the turn of the 20th century, Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov had a plan: Perhaps it would be possible to send several esteemed rebbes to the spiritual desert that was the goldeneh medineh and influence the masses? The blueprint looked good on paper and his two nephews agreed — but would it work in real life?

ITwas no secret that staying Torah-observant in the “treife medineh” of America at the turn of the 20th century was a heroic feat most European immigrants couldn’t endure. Rumors reached Europe that it was difficult, if not impossible, to raise a family of yerei Shamayim in the goldeneh medineh, since everyone was focused on amassing money, or at least staying afloat. And World War I only intensified the desperation, as masses of Eastern European Jews who had been uprooted from their homes and had lost their livelihoods found no other recourse than to emigrate overseas.

The spiritual situation of the struggling Jewish People in this New World, which at that time had a very paltry religious infrastructure and rabbinic leadership, gave many European rabbanim and rebbes no peace. One of those rebbes was Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov, a grandson of Rebbe Yisrael of Ruzhin. (The sons and sons-in-law of the “Heilige Rizhiner” established the courts of Sadigura, Skver, Stefanesht, Vizhnitz, Husyatin, and Tchortkov, and grandsons established the courts of Boyan and Bohush.)

Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov’s father was a son of the Rizhiner, Rebbe Dovid Moshe of Tchortkov, and his father-in-law was his father’s brother Rav Avraham Yaakov, the first Rebbe of Sadigura (in other words, Rebbe Yisrael married his first cousin, both of them grandchildren of the Heilige Rizhiner).

But instead of merely lamenting the fallen spiritual level of their brethren in America, Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov sought a way to help rectify the situation. He knew that the way to strengthen the masses and stem the tide of assimilation was by establishing educational institutions and yeshivos — but he was far away in Eastern Europe. Perhaps, he thought, it would be possible to bring several rebbes of refined character and esteemed stature to the spiritual desert that was America at the time (most of the Rebbes who settled in America came only after World War II).

The Tchortkover Rebbe knew his plan was unusual, and understood every rebbe who refused to take such a precarious step. And so, he set out to prepare a detailed blueprint that would preserve the spiritual level of the selected rebbe and his family, while at the same time enabling the rebbe to have as much influence on the surrounding Jews as possible. Today, of course, we don’t have a written outline of the plan, but we can piece together parts of it from a tradition passed down by the chassidim, and by putting together the details of the lives of the two rebbes who were sent by Rav Yisrael, as recorded by their confidants.

The first was Rav Yitzchak of Sadigura-Rimanov, who set off for America in the spring of 1924; and the second was Rav Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan, who followed with a pilot trip and settled there permanently three years later. They were both actually his wife’s nephews (and, for the sake of accuracy, his cousins as well), both of them grandchildren of Rebbe Avraham Yaakov of Sadigura.

Rebbe Avraham Yaakov’s son, known as the Pachad Yitzchak of Boyan, became the rebbe of masses of chassidim throughout Russia, Poland and Galicia. (Rav Avraham Yaakov of Sadigura lost both a son and a son-in-law in his lifetime, and his two remaining sons, Yisrael and Yitzchak, drew lots to determine who would take over for their father as Sadigura Rebbe. Rav Yisrael became the Ohr Yisrael of Sadigura, and Rav Yitzchak became the Pachad Yitzchak of the neighboring town of Boyan.) With the Pachad Yitzchak’s passing in March of 1917 after moving to the safety of Vienna, his four sons became rebbes: The oldest, Rav Menachem Nachum, led his community in Chernowitz; the second, Rav Yisrael, led a community in Leipzig; the third, Rav Avraham Yaakov, established a court in Lemberg (Lvov), and the youngest, Rav Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan, stayed in Vienna with his mother until her passing in 1922, and later established his court in New York (and was the grandfather of the current Rebbe).

Many people assume that Rebbe Yitzchak of Rimanov — a son of the Ohr Yisrael of Sadigura who became rebbe in Rinamov in 1913, ten years after marrying the granddaughter of the previous Rebbe of Rimanov — came to America for the purpose of raising funds. Some even add a baseless rumor that his tragic end at age 38 was related to the fact that he was carrying a lot of money on him.

But there is a clear mesorah in the Ruzhiner court that in fact, Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov chose these two rebbes of stature from his own family in order to execute his plan to bring spiritual salvation to the Jews of America.

Instead of merely lamenting the fallen spiritual level of the Jews in America, Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov thought of a plan to help bolster his brethren across the ocean

T

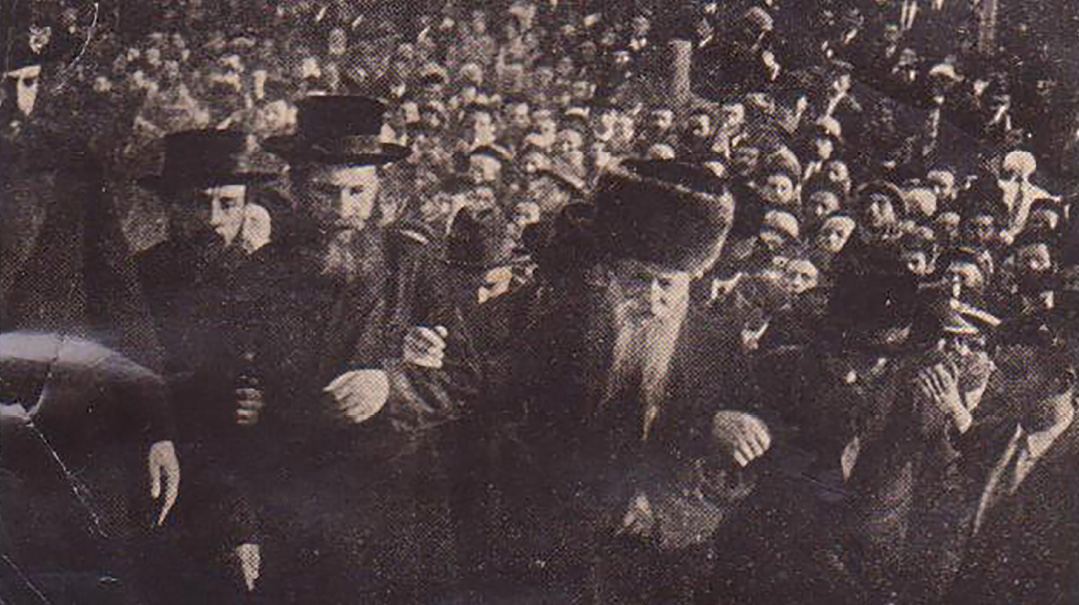

he New York policeman stationed on the Lower East Side was dumbstruck. He’d heard a lot about the waves of Jewish immigrants arriving to New York after the end of the Great War, but this was already 1924, and the first time that he was actually seeing such a mass of Jews in one place.

Most of them wore chassidic garb, and they were all streaming toward one specific location. The policeman stood on Clinton Street, afraid for the welfare of the crowd, and summoned backup to make order.

After making some inquiries, the officer learned that on that morning, a young chassidic rebbe had arrived at the port, and his arrival had generated a lot of excitement among the chassidim in the city — they were all headed in the direction of the Clinton Street shul where a reception was being held for him. The morning newspapers called him “the rabbi descended from the kingdom of the House of David,” while the Jews referred to him as “the first grandson of Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin to step onto the shores of the United States.”

Although we can’t know for sure, it can be assumed that Rav Yisrael of Tchorkov intended to send the two rebbes at the same time — initially for a trial period of a few months — in order to draw chizuk from each other and be able to preserve their spiritual level on foreign soil.

Rebbe Yitzchak left his family in Vienna, to where he and much of the extended Sadigura family escaped at the beginning of World War I (his plan was to eventually send for them), and embarked on his shlichus. At one point during Rebbe Yitzchak’s stay in America — it lasted about eight months — those close to him noticed that every decision and every excursion were made with careful calculations. Sometimes he’d refuse to take a particular trip that his confidants felt was very important and necessary. In time, he revealed the secret to his confidant, Rav Yosef Rappaport, who made the connection between all those seemingly strange decisions and the detailed instructions Rebbe Yitzchak had received from his uncle, Rav Yisrael of Tchortkov. In fact, when Rebbe Yitzchak’s cousin Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan arrived, he conducted himself in a similar fashion.

The first step Rav Yitzchak took was overturning the original plans regarding where he would live. At first, his supporters arranged a spacious, well-appointed apartment opposite the Sadigura Kloiz on the Lower East Side, but immediately upon his arrival, Rav Yitzchak asked them to find a simple apartment on a quieter street instead. Two weeks later, a new home was found for him on Attorney Street and a shul was opened adjacent to it.

Another practice that seemed to contradict the very purpose of his arrival was the fact that Rebbe Yitzchak seldom left his home. The only times he went out were to immerse in the mikveh or to visit gedolei Torah. He spent most of the day secluded, learning and engaging in avodas Hashem.

What did Rebbe Yitzchak seek to achieve in America if he didn’t interact with the people around him? Apparently, as the Rebbe himself later revealed to Rav Yosef Rappaport, Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov had delineated detailed instructions for when he could go out and when he should not leave. In fact, his cousin Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan maintained similar practices. (He also rarely left his house, except to immerse in the mivkeh. He once even remarked that although he was physically in New York, he himself was actually in Boyan.)

It’s noteworthy that the few times the Rebbe did emerge for Yom Tov tefillos, thousands of people came to witness his avodas hakodesh. When a local non-Jewish newspaper reported about the masses who came to see the Rebbe, the Rebbe, according to Rav Yosef Rappaport, became very distraught about these publications.

“The Ruzhiner Court never sought out such publicity,” the Rebbe said, and added a plea to his people to cut off ties with any newspaper that hounded the Rebbe’s court looking for events or morsels of information.

At one point, Rebbe Yitzchak told Rav Yosef Rappaport about some of his uncle’s conditions. When a group of outlying communities invited Rav Yitzchak to spend several weeks with them, Rebbe Yitzchak agreed, on condition that the stay not be longer than three weeks. When Rav Yosef Rappaport asked him about this condition, Rebbe Yitzchak replied that his uncle had instructed him never to spend more than three weeks away from his home. And even when he was at home, the Tchortkover Rebbe warned him not to go out to daven in other shuls during the week — and that he should only daven in the shul that was built for him in his own home. (After Rebbe Yitzchak’s sudden passing, Rav Rappaport published a kuntres that contained both words of chizuk and transcripts of many of his conversations with the Rebbe.)

Rebbe Yitzchak of Sadigura-Rimonov would heed his uncle’s call. Little did he, or the chassidim know, that it would just be a few short months

B

ut if you thought that because he was closeted at home, Rebbe Yitzchak was isolated from the Jews of America, that wasn’t exactly true. Because although he rarely left, many found him and would come pay him a visit. He helped and advised all those who turned to him, and, in the way of his forbears, was friendly even to those who had strayed from the path. He was a fervent ohev Yisrael, and he absolutely forbade any negative speech against another Jew in his presence.

During his stay in America, the spiritual condition of American Jewry gave Rebbe Yitzchak no rest. Although he deeply loved every Jew, he struggled to reconcile the fact that Shabbos desecration had become so widespread. He had always been physically frail, but facing this reality caused him so much internal anguish that he began to suffer heart problems.

In fact, he had already decided to return to Vienna, where he had lived temporarily after leaving Rimanov and where his family awaited him. The tickets to Vienna had already been purchased, but then the Rebbe began to suffer such breathing difficulties that he couldn’t even finish reciting Kiddush on Friday night. On Monday, 11 Kislev, he was diagnosed with severe pneumonia, but before his physician could begin treatment, the Rebbe began to hum the lofty niggun dveikus that he would sing while shaking the lulav on Succos (in Ruzhin, the rebbes can stand for many hours while shaking the arba minim).

And with this niggun, the Rebbe’s holy soul departed.

A shocked crowd of over 15,000 came to pay last respects to the young yet venerated Rebbe

T

he Jewish community sought to pay their final respects, and appointed a special committee to handle the details of the burial. But where would he be buried?

Several kehillos who had burial sections in Jewish cemeteries around the New York area each wanted the privilege of having the holy rebbe buried among their plots.

Rav Yisrael Gutman of Kamenitz and Rav Ephraim Zalman Halpern of Denver were appointed to resolve the issue, ultimately deciding that Chevras Chassidei Sadigura would merit to have the Rebbe buried in its chelkah in Mount Zion cemetery in Queens, on condition that 32 plots would be designated and sold, the income of which would be transferred to support the Rebbe’s widow and children who were in Vienna.

Although in his lifetime the Rebbe insisted on eschewing any media publication, it was impossible to keep the mass levayah out of the media — as over 15,000 broken Jews converged on the outskirts of a cemetery plot.

The Rebbe’s family eventually migrated back to Rimanov, where Rebbetzin Sarah was murdered by the Nazis in Elul 1941. Rebbe Yitzchak’s son, Yisrael, moved to America and survived the Holocaust. His son, noted talmid chacham, baal chesed, Madison Avenue publicist and university lecturer Reb Yitzchak (Adam) Friedman, passed away from Covid in 2020 at age 75.

(Left) From the Boyaner kloiz at 247 East Broadway, Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan was less interested in building up his own court than laying the groundwork for bringing chassidic life to American soil

(Right) The Rimanover Rebbe’s surviving grandson, Reb Yitzchak (Adam) Friedman, with his third cousin, the current Boyaner Rebbe

T

he Tchortkover Rebbe’s planned spiritual revolution sustained a difficult blow with the tragic and sudden passing of Rebbe Yitzchak of Rimanov. Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo of Boyan was actually already on his way to America for a pilot trip with the enthusiastic encouragement of the chassidim of the Boyaner kloiz on the Lower East Side and the second phase of the plan set in motion by his uncle, when Rebbe Yitzchak was suddenly niftar. Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo arrived on the 18th of Kislev, just a week later.

The visit lasted close to a year, and he spent the next year back in Vienna considering his future. Of course, his uncle Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov practically pleaded with him to go back, insisting that American Jews deserve a rebbe in their midst as well.

When Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo came back to the US in 1927, his initial years there, engaged in Torah and avodas Hashem in seclusion, very much patterned after the Tchortkover’s instructions to Rebbe Yitzchak. He spent most of his days in the “daven shtiebel,” a secluded room adjoining the beis medrash, as per the custom of the rebbes of Ruzhin.

Still, although he didn’t work to build his court and expand his institutions, Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo lay the groundwork for bringing chassidus to America from the kloiz at 247 East Broadway on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The Boyaner kloiz was a haven of holiness among the bustling streets of the Lower East Side, and while the Rebbe exuded a sense of nobility, he was extremely warm and embracing, which appealed to many young Americans who’d never seen a rebbe before. Quite a number of secular Jewish youths became baalei teshuvah through their contact with the Rebbe, who succeeded in proving that being chassidic could still be a viable lifestyle, even in America.

The Rebbe lived in the same simple apartment over the kloiz for 40 years and never replaced the original furniture. And whenever his travels were on the cheshbon of public funds, he refused to take a taxi and would travel by subway instead.

In 1967, the Rebbe suffered a stroke, forcing him to move near his children on the Upper West Side, where another kloiz was established. In the winter of 1971, Rebbetzin Chava Sara passed away, and a few months later, on the 5th of Adar, the Boyaner Rebbe left This World.

From the time he arrived in the US, the Rebbe, self-effacing as he was, took an active role in American Jewish leadership. Over the years, as many more rebbes found their way to American shores, he founded and was president of the Agudath HaAdmorim, under the banner of which he participated in the famed Rabbi’s March in Washington in 1943.

In 1939, as the trickle of Jews from Eastern Europe became a river, the American Agudath Israel was founded, with the Boyaner Rebbe as its first vice president and member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. In conjunction with the Agudas HaRabbanim, he helped organize the Vaad Hatzalah during World War II and assisted in the rescue of Torah leaders in Eastern Europe. The Satmar Rebbe received his first financial assistance in America from Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo, as did many other rebbes.

Also in 1939, another eminent rebbe from the Ruzhiner line arrived in America from Vienna: Rav Avraham Yehoshua Heschel of Kopyczynitz, also a great-grandson of Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin. His mother, the wife of Rav Yitzchak Meir of Kopyczynitz, was a daughter of Rebbe Mordechai Shraga Feivel of Husyatin, the youngest son of the Ruzhiner. (The current Boyaner Rebbetzin is a granddaughter of the Kopyczynitzer Rebbe, Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo’s good friend and distant cousin.)

The Kopyczynitzer Rebbe (who passed away in 1967) immediately jumped in to help the Boyaner Rebbe’s efforts to firmly establish and strengthen Yiddishkeit in America, and served alongside him on the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. He, like his good friend and distant cousin Rebbe Mordechai Shlomo, didn’t invest much in building his own court, but was instead dedicated to helping Yidden and providing them with assistance in any way they needed. (A reflection of their involvement in other chassidic courts is evidenced by the fact that they were the two people the Lubavitcher Rebbe Rayatz sent mishloach manos to every Purim, a custom continued by the Lubavitcher Rebbe after his father-in-law was niftar.)

It’s close to a hundred years since the brave rebbes of Ruzhin threw in their lot with the American Jewish frontier. Yet today, when it’s “easy” to be chassidish, few people know how much American Torah Jewry — chassidic or otherwise — owes its existence to the plan of Rebbe Yisrael of Tchortkov and his hoped-for revolution.

At the kever of Rebbe Yisrael of Ruzhin. The Heilige Rizhiner’s sons and sons-in-law branched off to spread chassidus all over Europe

Following the Rebbe Trail

T

he Ruzhiner dynasty can be quite confusing because of its many branches and descendants. Within that dynasty, perhaps the most complex is the Sadigura offshoot. One reason for the confusion is that there were several splits along the way, and another is because the names of the rebbes often repeat.

Rav Avraham Yaakov was a son of the Heilige Rizhiner and the first Rebbe of Sadigura, and the first split in the Sadigura court began in 1883, nearly 33 years after the “Rebbe Hazaken,” Rav Avraham Yaakov (“the first”), began to lead. As his oldest son and then his son-in-law passed away in his lifetime, there were two sons remaining who were worthy of leadership: The older of them was Rav Yitzchak, and the younger one was Rav Yisrael. As both were qualified to lead, they agreed to draw lots. Rav Yitzchak (the Pachad Yitzchak) left Sadigura for nearby Boyan, and Rav Yisrael (the Ohr Yisrael) became the second rebbe of Sadigura.

The second split occurred after the passing of the Ohr Yisrael in Tishrei 1907. He was succeeded by his son, Rav Aharon (the Kedushas Aharon) — but Rav Aharon died when he was just 36, and his son Mordechai Shalom Yosef was only 16 at the time. And so, Rav Aharon’s brother Avraham Yaakov (“the second”), known as the Abir Yaakov, took the helm of the chassidus and reestablished it in Tel Aviv. He was the third Sadigura Rebbe, and became one the leading Rebbes in Eretz Yisrael and a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah. (Another son, Reb Shlomenyu, originally served as a rebbe as well but ceased using this title when he became heavily involved in rescue work during World War I, eventually following his brother to Tel Aviv and davening in his court there.)

Meanwhile, 16-year-old Mordechai Shalom Yosef established a shul and yeshivah in the town of Pshemishyl, eventually moved to the US and became Rebbe of Sadigura in Crown Heights until he made aliyah with the passing of his uncle, the Abir Yaakov. He moved the chassidus to Bnei Brak, and became the fourth and longest-serving Rebbe of Sadigura. His son was Rav Avraham Yaakov (“the third”), known as the Ikvei Abirim and the fifth Rebbe, who passed away in 2013. And his son was Rav Yisrael Moshe, the sixth Rebbe who passed away in 2020, leaving three sons who lead the batei medrash in London, Jerusalem and Bnei Brak.

Now, to backtrack to the Ohr Yisrael, the second Rebbe of Sadigura: In addition to his sons who served as rebbes of Sadigura, his youngest son, Rav Yitzchak of Sadigura-Rimanov, is the young rebbe in the center of our story.

The connection between Rimanov and Ruzhin begins with a young boy who appeared one day in the beis medrash of Rebbe Menachem Mendel of Rimanov. The boy, named Tzvi Hirsch, was orphaned of both parents, and in Rebbe Menachem Mendel’s beis medrash, he made such great strides that the Rebbe asked him to become his regular meshamesh. His closeness with Rebbe Menachem Mendel continued even after he married, remaining the Rebbe’s meshamesh bakodesh. Before his passing, Rebbe Menachem Mendel, whose sons didn’t want to replace their father, instructed that the leadership should be transferred to his loyal meshamesh, Rav Tzvi Hirsch, who was called Rav Tzvi Hirsch Meshares (which in Hebrew means “the meshamesh.”)

At first, he too demurred, but eventually he became known as Rebbe Tzvi Hirsch of Rimanov. Despite his tragic life — he lost 14 children — he was always b’simchah, and over the years, thousands of chassidim streamed to him — and even Rebbes came to bask under his influence. With his passing, he left behind a son, a daughter, and a widow (his third wife).

At the time, Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin also became widowed, and he married the widow of Rav Tzvi Hirsch and raised her children in his home. Rav Tzvi Hirsch’s young son, who was raised by his stepfather, Rav Yisrael of Ruzhin, was heir to the Rimanover dynasty and became known as Rebbe Yosef of Rimanov. Years later, Rav Yitzchak, the Ohr Yisrael’s son, married the granddaughter of Rav Yosef of Rimanov. After Rav Yosef’s passing in 1913, his grandson-in-law, Rav Yitzchak, was asked to succeed him as Rebbe. And from that point on, the Ruzhiner’s great-grandson became the Sadigura-Rimanov Rebbe.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.