A Shaliach Like No Other

| November 8, 2022Rabbi Chaim Zvi Schneerson's eloquence in English, along with his uncanny knowledge of geopolitical issues, set him apart from other shadarim

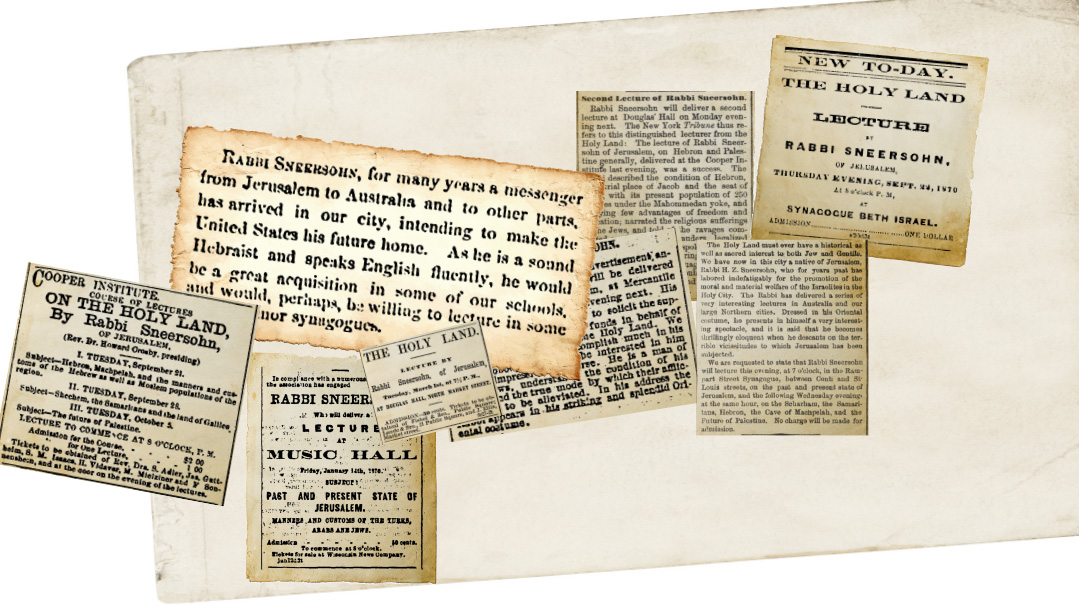

Title: A Shaliach Like No Other

Location: United States of America

Document: Assorted Newspaper Clippings

Time: 1868–1870

“Among the callers on the President yesterday was Rabbi Sneersohn, from Jerusalem, whose lectures on the Holy Land and whose interview with the Secretary of State have been alluded to in our columns within a week past. The President rose courteously to receive the Rabbi, who addressed him in the language which follows:

“Mr. President: Permit me to give my thanks to the Almighty, Whose mercy brought me here to behold the face of the chosen by the millions of this great nation. Blessed be the L-rd, who imparted from His wisdom and from His honor to a mortal…”

Rabbi Chaim Zvi Schneerson was born in Lubavitch in 1834, a great-grandson of the Baal HaTanya, Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi. As a young boy, he emigrated along with his family to Eretz Yisrael. As he developed into a young Torah scholar, his talents and unusual charisma became clear to all who met him. At a young age, he embarked upon a career as a shadar (shaliach d’rabbanan, a traveling fundraiser for institutions in Eretz Yisrael), representing Kollel Chabad as he traveled across Europe and as far abroad as China, Persia, India, Australia, and New Zealand.

Rabbi Schneerson was as exotic as he was intelligent and possessed a rare flair for the dramatic, as is evident in newspaper reports of his travels: “The lecturer made his appearance on the stand dressed in a long yellow gown, partly covered by a white one. He wore on his head a red worsted cap, with a large black tassel pendant behind. The rabbi is rather a small man physically, with black hair, piercing blue eyes, and a swarthy complexion.”

In addition to raising funds, Rabbi Schneerson worked to establish agricultural settlements and spoke of the imminent arrival of Mashiach, which would bring Jewish sovereignty to the Holy Land. Fluent in several languages, he often penned articles and even served as a correspondent for many Jewish newspapers of the era. Without any prior knowledge of either, his views regarding the process of Jewish sovereignty in Eretz Yisrael corresponded to the emerging positions espoused by both Rav Zvi Hirsch Kalischer and Moses Hess.

He garnered great respect from the communities he visited and was able to raise significant funds to help house and feed the poor residents of Jerusalem and Chevron. Yet life in the Holy Land became increasingly difficult as the Jewish community faced restrictions from the Ottoman government.

On one fundraising trip, he stopped in Paris, where he forged a connection with the personalities and activities of the Alliance Israélite Universelle. He then proceeded to England to raise funds on behalf of the Jewish community in Teveria, where he had taken up residence and endeavored to establish an agricultural settlement on its outskirts. When the British community failed to meet his fundraising expectations, he went to the United States on his own initiative, touting his various ideas and projects among both the Jewish and general populations.

When Rabbi Schneerson arrived in America in 1869, his eloquence in English, along with his uncanny knowledge of geopolitical issues, set him apart from other shadarim. One Jewish newspaper remarked that it was a true pity Rabbi Schneerson was not there to stay, for he was eminently qualified to lead in a way that most local rabbis were not.

With the assistance of his hosts, he was able to obtain an audience with Secretary of State Hamilton Fish to plead his case. Fish was immediately taken by his guest and offered to arrange a meeting with President Ulysses S. Grant. Rabbi Schneerson used the meeting with President Grant to request that the American consul to Jerusalem, General Victor Beauboucher, be replaced, as he was unsympathetic to the city’s Jewish population.

President Grant, eager to prove he was a friend of the Jewish People following his controversial 1862 order to expel Jews from the district of Tennessee, (which encompassed portions of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Mississippi), acquiesced to the rabbi’s plea. Rabbi Schneerson would remain friends with President Grant, greeting him in Jerusalem when the former president visited in 1878.

In his later years, Rabbi Schneerson was accused of attempting to undermine the chalukah system of the Old Yishuv, and was the victim of slanderous personal attacks. He made one last trip abroad in 1882 at the age of 48, this time to South Africa, where he succumbed to disease and was buried.

The Crusader Consul

Victor Beauboucher was a French journalist who came to America to report on the Civil War for a Belgian newspaper and ultimately volunteered for the Union Army. As a result of injuries sustained at the Battle of Coal Harbor, Beauboucher’s left leg was amputated. Although he never became an American citizen, President Grant rewarded him for his heroism by appointing him US consul to Jerusalem. Initially, his appointment was celebrated by the Jewish community, evidenced by the Hebrew Messenger referring to Beauboucher in 1867 as “one who has evinced the utmost kindness to our co-religionists.”

This relationship would soon change drastically. Mordechai Eliyahu Steinberg, a Prussian Jew ensnared by Jerusalem missionaries who converted his family to Christianity, lost his wife and then became gravely ill. Before he died in 1865, he returned to his roots, but his elder daughter had married out. Steinberg asked Rabbi Ari Marcus to look after his younger daughter Sarah. In 1868 she was visited by her apostate sister, who asked that Sarah come live with her.

When Sarah refused, the apostate sister enlisted Beauboucher, who appealed to Ottoman authorities to arrest Rabbi Marcus. The next day, under pressure from Jewish leaders, the authorities appointed a mediator, who asked Sarah whether she wanted to remain a Jew. When she answered yes, the mediator immediately released Rabbi Marcus and returned Sarah to him.

After the incident garnered attention across the Jewish world, Beauboucher justified himself to superiors, claiming he thought the girl was a victim of Jewish religious fanaticism, and he acted only out of concern for her well-being.

The episode was enough to warrant his removal, though it’s likely that this was a mutual decision.

Eretz Yisrael and Romania was the title of Rav Schneerson’s most famous work, but also the primary focus of his lifelong activism on behalf of Jews. In 1860 Rav Schneerson took part in the initiative to build the Batei Machseh neighborhood for the poor of the Old Yishuv in Jerusalem. He subsequently embarked on a long trip to raise funds and awareness in Australia, where his speeches electrified Jews and Christians alike. Several of his extended visits to Romania led Rabbi Schneerson to take up the cause of that country’s Jews, and he lobbied world governments on their behalf, notably convincing President Grant to appoint a Jewish lawyer named Benjamin Franklin Peixotto as American consul in Romania.

Research by Professor Jonathan Sarna and Israel Klausner was utilized in the preparation of this column.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 935)

Oops! We could not locate your form.