Seller’s Market

| October 6, 2022Why do arba minim sellers still scramble to get a table in the Shuk?

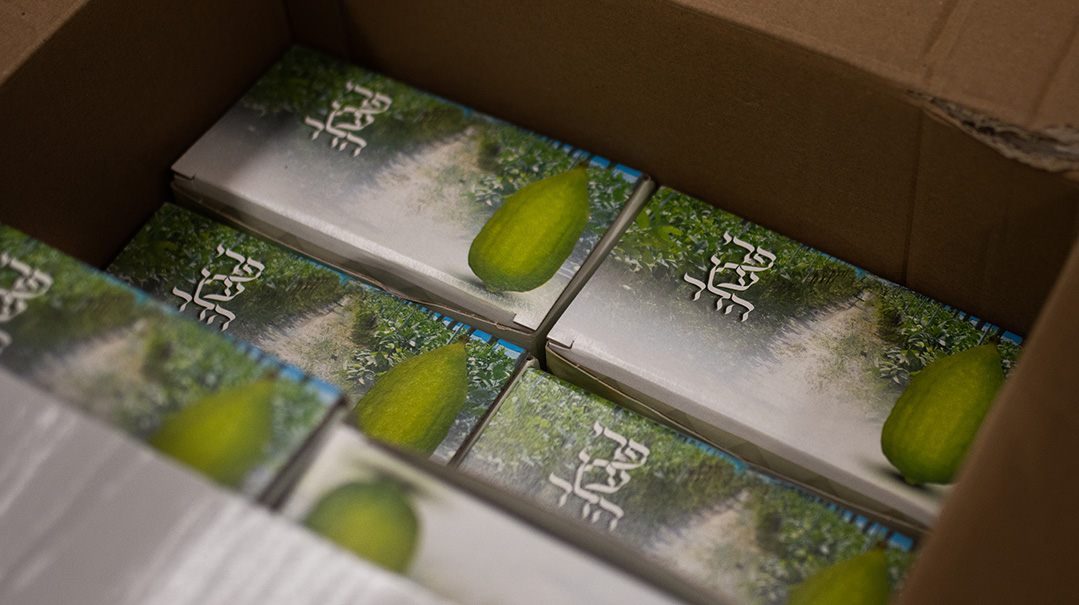

Photos: Yisroel Tesser

The competition is tough, the hours are long, there’s no guarantee of quality stock, and the profits are a gamble. So why do arba minim sellers still scramble to get a table in the Shuk? Because if you have a passion for the mitzvah and love helping customers, you just can’t stay away

It’s the quintessential Erev Succos scene.

Hear vendors loudly hawking their holy wares; watch men poring over hundreds of arba minim sets, squinting and scrubbing and scrutinizing the most minute marks. Take in the entrepreneurs marketing their creative inventions: a lulav holder that keeps your lulav steady even when travelling or a waterproof patent leather ultralight esrog box. Smile at hopeful youngsters who dart around, quickly tying lulav rings in the hopes that they’ll earn a few coins.

But you’re not in Yerushalayim — or even Eretz Yisrael for that matter. You’re standing in New Jersey, taking in the scene of the Lakewood Daled Minim Shuk. The Lakewood Shuk operates during the four-day period between Yom Kippur and Succos, when arba minim shopping is at its peak. What began 25 years ago as a convenience has evolved into a central part of the pre-Yom Tov experience in the area.

The Shuk started when some local enterprising esrog sellers decided to band together and bring their goods to one central location for the final stretch of the pre-Succos shopping spree. Together, they formed Lakewood’s “Daled Minim Shuk” in the basement of Beth Medrash Govoha. The arrangement was a boon to everyone involved: Customers had a greater selection; sellers had a larger client base; and with a number of capable rabbanim on site, the process of getting that final stamp of approval for esrogim was eased.

The Shuk’s popularity forced the sellers to upsize from the original basement location, which was getting cramped, to the yeshivah’s large succah. Within a few years, even that wasn’t big enough. Tables began to spill out of the succah, crowding the driveway and parking lot. Still, for 23 years, the Shuk remained on Seventh Street, until the pandemic and ensuing safety precautions forced organizers to relocate to the oversized parking lot of a local wedding hall. When even this larger location couldn’t accommodate the bustling experience, the Shuk relocated once more, this time to the parking lot of the local Blue Claws stadium, where an enormous, 10,000 square-foot circus tent is erected annually exclusively for the Shuk.

To get an insider’s view of the industry, Mishpacha spoke with Avi Klugman, a longtime arba minim seller and a fixture of the Lakewood Shuk. Avi’s first experience at the Shuk was as a kid who sold fresh lulav rings; he eventually turned that into a thriving arba minim enterprise. Today, Avi serves as COO of a commercial finance company, yet he still manages to find time to moonlight as the manager of the BMG Shuk. As he was gearing up to greet the crowds, Avi filled us in on how he got started, what it takes to be successful in the arba minim industry, and what goes into running such a mammoth operation.

on

my family’s history in daled minim

My great-grandfather was tasked with getting a set of arba minim for his community in Fulda, Germany and traveled quite a distance to purchase a set. When he headed home, he mentioned to the driver that the esrog needed delicate handling and that he should guard it with extra care. When they finally arrived in Fulda, my great-grandfather opened the box, and to his horror, the pitom had cracked off the esrog! The driver, noting his horrified expression, told him not to worry. He explained that he knew the pitom was valuable and so he’d removed it and wrapped it in separate packaging so it would stay safe….

During one shemittah year, Rav Shach and the Steipler wanted lulavim specifically from Arizona. My father and his friend went to the Lower East Side to purchase such lulavim and brought them to Eretz Yisrael.

on

my first foray into the business

I joined the Shuk when I was eight years old. I’d just go and hang around there, peeling the leaves off some pasul lulavim and making rings I hoped people would buy. At some point, I realized that the leaves begin to dry out the minute they come off the stem, so I started refrigerating them in my parents’ garage to keep them moist. Of course, I charged more for my “premium” rings than the other boys. I also used incentives to entice customers to buy from me: I gave “corporate discounts” for anyone who ordered over 50 rings and even offered delivery — my mother drove me around after school so I could deliver to my customers.

Eventually, someone asked me to sell aravos for them. After a few years, I was able to contact the supplier directly, and it became my own business. I was still a youngster and hesitant to walk home with so much cash, so a family friend who lived near the yeshivah, Reb Aron Stefansky z”l, offered to let me use a safe in his home. The deal was I could deposit my earnings every night, but I had to give the maaser to the Brisker rosh yeshivah, Rav Avraham Yehoshua Soloveitchik, for the yeshivah.

on

a lesson I learned

When I was about bar mitzvah age, I decided to try my hand at full sets: lulavim, esrogim, hadasim, and aravos. I was introduced to a mocher from Eretz Yisrael, and I negotiated with him what I thought was a great price — until the product came, and I realized I’d botched up. I hadn’t done my research properly, and the batch I got was pretty lousy. It was rough, but I learned about the hazards of where and from whom you get your supply, and the whole experience enabled me to fine-tune my business model. The next year, I managed to get in touch with the right people and obtain a superior product for a fair price.

on

Hashem’s helping Hand

During one of the first years that I sold arba minim, I made a one-day sale out of my parents’ garage before bringing my wares to the BMG Shuk. The advantage of doing it there was that I could lower my prices because the location was rent-free, and I could pass those savings on to the customer, but the drawback was that there was no rav on site, so no one could give people the confidence that my product was up to par. But then, a car broke down on my parents’ corner. The driver was a son of Rav Mendel Rabinowitz ztz”l — the undisputed expert in arba minim — and he had learned from his father. I called Chaverim for him and asked if he’d be able to stop by the house so my customers could show him their esrogim, which he did.

on

business advice I incorporated as a mocher

My grandfather, Mr. Julius Klugman z”l, was not only a legendary askan in Washington Heights, he was a successful businessman as well. When I told him that I had started selling arba minim, he gave me this advice: Always make customers feel like they are making a choice, but don’t offer too many choices, in order not to confuse them. When I first got a table in the Shuk, I implemented his advice by positioning myself toward the middle of the Shuk. This way people wouldn’t feel like they were settling for the first product they chanced upon, but rather, by coming to me, they were making a choice. Today, when we arrange the tables in the Shuk, I put the vendors selling succah decorations around the perimeter of the tent and the esrogim tables in the center, because customers won’t buy from the first table they encounter, and with all the esrogim in the center, they’ll focus on the products and not choose one over the other based on location.

on

my most meaningful client

I remember one rosh yeshivah who selected almost every variety of esrogim — a Braverman, a Chazon Ish, a Moroccan one. His bill was over $2,000! I couldn’t imagine how he could afford it. He told me that he discussed it with his family, and his kids agreed to forgo having dips at their Shabbos seudah for the entire year, so they’d be able to buy these esrogim. I also remember that when I was a kid, Rav Yisroel Newman, one of the Beth Medrash Govoha roshei yeshivah, saw me selling lulav rings, and he came over to me and placed an order. I don’t think he actually needed the rings, but he knew it would make me very proud to know the Rosh Yeshivah utilized my services.

on

my most memorable order

When I started shipping around the country, Jews with varying degrees of affiliation would place orders. Once, someone in Manhattan who was a bit distant from Yiddishkeit ordered a very expensive set. He was so grateful that we were able to get it to him, he left me a $150 tip after delivery. Another memorable request was the customer who asked me to send him fresh new hadasim and aravos every day throughout Succos.

on

the inevitable mishaps

One year, a Succos program ordered thousands of hoshanos for their guests. I sent the aravos up in a refrigerated truck so they would stay fresh all the way from Lakewood to the Poconos. I miscalculated how cold the trucks get, though — by the time it arrived, the entire shipment had gone bad. They were all black. I had to quickly find another driver who could make the trip with a new batch of aravos, this time in a regular truck. And of course, there are always mishaps when it comes to the esrogim, like the customer whose kid breaks the pitom off his $500 esrog right before Succos. I always keep an extra ten to fifteen esrogim in my house over Yom Tov for such cases.

on

equipment I always have on me

Fun-Tak mounting putty to remove a speckle without damaging the esrog, or worse, making it pasul, Q-Tips to gently clean esrogim, and a loupe to check bletlech on the esrogim.

on

advice for those entering the business

From a purely business perspective, this isn’t the easiest industry. There’s a lot of competition, not a lot of money, very long hours, and very intense work. When you speak to people who do this, you find that they aren’t necessarily in it for the money, but because they love arba minim. If you have a passion for the mitzvah and appreciate helping customers, it’s the greatest experience.

on

the ins and outs of the Shuk

Sellers don’t vary much from year to year, because we have a chazakah system: if you had a table the year before, you’re entitled to one again. After that, it’s first-come, first-serve. Aside from the arba minim, people sell succah decorations, as well as yarmulkes, tzitzis, white shirts — basically anything you might need for Yom Tov. The only product that isn’t sold here is food. When we moved to the stadium, the roshei yeshivah advised us against it. They said this way people would come exclusively to shop for arba minim and Yom Tov needs, not just to hang out, and the atmosphere would be cleaner.

on

how I came to run the Shuk

When the pandemic hit, the administration of BMG decided not to reopen the Shuk, but the people needed it, so I made some calls and was able to access Lake Terrace. That year, I ended up arranging the whole thing.

on

how many esrogim the average customer inspects before selecting one

For balabatim, I would say the average is three, but among yungeleit, it could be up to 15.

on

the vibes

There’s something very special about the atmosphere here. When we were still located near the yeshivah, morahs would bring their classes to watch the men in action. Seeing customers running back and forth with the arba minim makes kids really excited for Succos. We get a decent population from outside the immediate Lakewood-Jackson-Toms River-Howell-Manchester crowd as well. People come in from Cherry Hill and Edison, and they’re mesmerized by the scene.

on

injuries on the job

Aside from almost poking out my eye while checking hundreds of lulavim? None.

on

being extra mehudar

One popular hiddur is that the hadas be meshulash, meaning every set of the three leaves on the hadas emerge from the stem at precisely the same level. Now, the leaves on the hadasim aren’t that big to begin with, so to discern whether an entire branch is meshulash takes a lot of concentration and patience. Once a choshuve yungerman was sitting for hours on end, looking at hundreds of hadasim to find three perfect ones. Eventually, he finally found what he was looking for. He put down the hadasim and began checking aravos. After about 15 minutes of him scrutinizing the aravos, I asked him what he was looking for.

“I’m checking to make sure the aravos are meshulash,” he responded.

But aravos don’t have such a hiddur; they don’t have rings of three leaves at all. This man had spent so much time on the hadasim that he automatically started checking for the same hiddur on the aravos!

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 931)

Oops! We could not locate your form.