Every Scroll a Story

| October 6, 2022The sifrei Torah stored in Israel’s National Library have been on a long journey of their own until they were brought safely to the Holy Land

Photos: Assaf Pinchuk and Hanan Cohen

It’s been two decadessince planning began to construct a new building for Israel’s National Library, and seven years since ground was broken. The building, located on Rechov Ruppin, the “Museum Row” of Jerusalem, is scheduled to open around Pesach time, and the colossal job of moving more than four million books and hundreds of thousands of manuscripts, maps, and memorabilia from the old building into the new has already begun.

Among the millions of items traveling to their new home are a number of sifrei Torah. For many of these seforim, this short trip (the old building is less than a kilometer from the new) will be the culmination of a journey that took place over thousands of years and across countless miles.

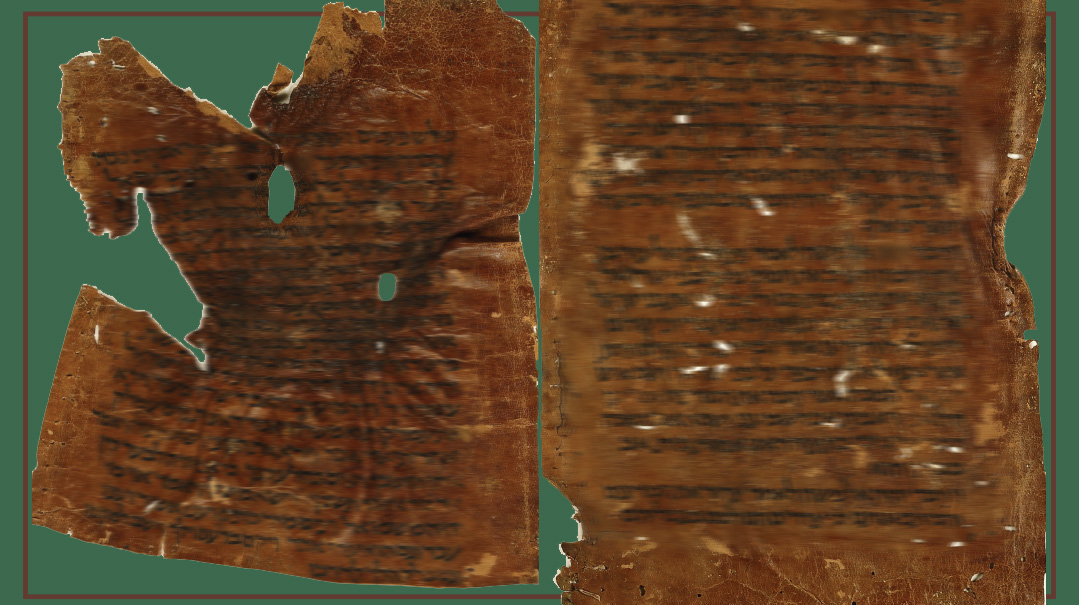

All that’s left of this ancient Yemenite sefer Torah are a few fragments, but it’s clear that the words haven’t changed

Words That Bind

No one is certain when Jews first came to Yemen. Some traditions date the community back as far as the reign of Shlomo Hamelech, who is said to have sent Jews to Yemen to buy gold and silver for the Beis Hamikdash. Others connect the ancient kehillah to the time of the first churban; there are those who say that Yirmiyahu Hanavi sent 75,000 Jews to Yemen right before that tragic destruction. Archaeologists have found written records from almost 2,000 years ago that mention the building of synagogues in Yemen.

When printing began, bookbinders would strengthen the spines of the books by sewing parchment fragments into the bindings. Housed in an airtight vault in the National Library are fragments of an ancient Yemenite sefer Torah. These fragments, about 1,000 years old, were sewn into the spines of books and thus preserved. Holes in the Yemenite Torah fragments clearly indicate the bookbinder’s stitching.

The history of Yemenite Jewry, like so many communities in galus, includes times of great prosperity, but also times of terrible persecution. Seeing pictures of these fragments — which, to help preserve them, are rarely taken out of their vault — one can’t help speculating about their backstory. How did fragments of a sefer Torah find their way into book bindings? Might it have happened during some terrible time of persecution, when the holy parchment was desecrated and sewn into spines of books?

Some scholars suggest a more optimistic scenario. When a sefer Torah became pasul, too old or damaged to use, the tradition was to bury it. But in a time and place where resources were scarce, another tradition arose. Bookbinders would take pieces of the sefer Torah (halachically permissible or otherwise) and use them to strengthen the bindings of other sifrei kodesh. When these seforim were damaged, they were placed in genizah — and the pieces of the Torah were discovered hundreds of years later.

And what about the original Yemenite sefer Torah itself, written 1,000 years ago? Had it originally been placed in an aron kodesh in one of the shuls mentioned in ancient texts? Was the sofer stam who wrote it a descendant of a Jew who helped decorate the Beis Hamikdash in gold and silver? Answers to these questions are lost in the mists of time.

What’s clear is that though these holy fragments come from a sefer Torah read long ago and far away, the words written on them are the same as the ones we read today. Yemenite parchment is a unique color, and some of the letters of their sifrei Torah look slightly different from those of other communities, but the words of a Yemenite sefer Torah — and of the remaining fragments of this most ancient treasure — are the same words that Jews all over the world and throughout time have read and cherished, have sometimes died for and always lived by.

Oops! We could not locate your form.