Blast from the Past

| September 13, 2022At 101, Yaakov Aharoni is the last surviving shofar blower of an era when sounding the shofar at the Western Wall meant almost certain incarceration by the British

Photos: Itzik Blinitsky

IN the late 1920s, the local Arabs had begun rumbling about how blowing the shofar at the Western Wall was an insult to Islam, and by 1930, the legislative authority of the British Mandatory government stipulated that the Moslems’ ownership rights to the Temple Mount also encompassed the Kosel area (which at the time was just a few meters wide, pushing up against Arab houses). As a result, Jews were banned from blowing the shofar at the Wall, even on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

The ban was an outrage, even to the most pacifist Jews of the Old Yishuv, and from the first Yom Kippur in 1930, when Lubavitcher chassid Rabbi Moshe Segal hid a shofar under his tallis and blew the tekiah gedolah, the shofar was actually blown every year until 1948, smuggled in by intrepid young men who would be beaten and arrested in the aftermath.

It was a real technical challenge as well, as large numbers of British policemen were stationed along the routes to the Kosel and conducted thorough searches of the Jews heading toward the Wall. The boys, who figured out creative ways to smuggle in the shofar, worked in teams of three so if one was caught, the others still had a chance — although it would usually mean spending at least a night, and up to six months, in the Kishleh, the Turkish-era police building and prison that’s still at the entrance to the Old City.

But that didn’t deter them. “This was about the lifeblood of the Jewish people,” says centenarian Yaakov “Sika” Aharoni, who blew the shofar at the Kosel in 1936 when he was 17.

About ten years ago, the six still-living shofar-blowers were located and were brought together — with wheelchairs and walkers — for a reunion at the Kosel, organized by the Toldot Yisrael historical society. “People can’t imagine it today, but as soon as we blew the shofar, the commotion started,” Avraham Elkayam a”h, who blew the shofar in 1947 at age 13, told the organizers. “The British started beating people with clubs.”

In June 1967, as the IDF miraculously routed the Jordanian legion, liberating the Kosel and reuniting the Old City with the rest of Jerusalem, Avraham Elkayam, a reserve soldier then, was fighting in the area and quickly made his way to the Kosel. There he saw an emotional rabbi in his sixties, standing by the Kosel that had been in Jordanian hands for 19 years, blowing a shofar, and Avraham asked him if he might have a turn as well. Avraham explained to the rabbi that he was the last person to sound the shofar at the Kosel before it was wrenched away, and it would mean a lot to him. The rabbi handed Avraham the shofar and hugged him, telling him that he, in fact, had been the first — it was Rabbi Moshe Segal, who started the tradition back in 1930.

Yaakov Aharoni is 101 today, and the only surviving shofar-blower of that era. He no longer has the koach to blow those tekios, but his spirit and his memory are as strong as ever. Nearly 86 years later, he still remembers Yom Kippur 1936 in minute detail:

“A few weeks before Yom Kippur, I was summoned to a meeting with Yaakov Meridor, my Irgun commander, who asked if I’d be willing to blow the shofar at the Kosel. ‘But,’ Meridor warned me, ‘you know it means you’ll probably sit in jail.’ I didn’t care — for me it was a great honor, and my first Irgun assignment.

“Two of us were chosen,” Aharoni continues. “My friend Yisrael Tevuah would blow for the Ashkenazim, and I would blow for the Sephardim. If one of us would get caught, the other would hopefully take over.”

The first hurdle was getting the shofar into the area. “They checked us from head to toe at the entrance,” he says. “There was a woman standing next to me, and I asked her in Yiddish if she’d take the shofar and put it under her cloak. Everyone was in it together, and she was happy to oblige. Because when the shofar sounded, it was like the Shechinah descended on all of us.”

Aharoni, who learned for several years in Yeshivat Porat Yosef and was, at 17, already a proficient chazzan, organized and led his own minyan at the far edge of the Kosel. As he began Avinu Malkeinu, the last tefillah before kabbalas ol malchus Shamayim and the shofar blast, his antennae were up: There were British police all around, but closest to him he noticed a police plant who was dressed like a Jewish worshipper. As Aharoni moved through the Avinu Malkeinu tefillah, he chanted in the same singsong nusach, “Avinu Malkeinu, pay attention to the guy in the cap, he’s a secret agent on the side of the enemy. Surround me, so that he won’t be able to lay a hand on me.”

Until that minute, the crowd had no idea who the hoped-for shofar-blowers would be, but they were quick to pick up on Aharoni’s signal. They made a human wall around him, and he let out the most memorable tekios of his life.

The Kosel Hamaaravi, guarded by British soldiers. Who would succeed in defying the law and blow the shofar at risk of imprisonment?

F

or Yaakov Aharoni, blowing the shofar at the Kosel was the first in a long chain of underground activities against the British, for which he earned the nickname “Sika” — a spin on the Sikarikim zealots during the Roman conquest of Eretz Yisrael before the destruction of the Second Beis Hamikdash.

In fact, his own family tree goes even further back than that, to the time of the First Temple in ancient Jerusalem. “In our family,” says Aharoni, who today lives in Ramat Gan with his wife of many decades, “they never said, ‘Our grandfather immigrated to Yerushalayim.’ They always said, ‘Our grandfather has returned to Yerushalayim.’ ”

Indeed, his grandfather, a leader of the Isfahan community in Persia, returned to Jerusalem in 1886, the fulfillment of the dream after nearly a hundred generations in exile. And Aharoni’s earliest associations are linked to the holy city.

“One picture indelibly stamped in my memory since childhood is the image of Tikkun Chatzot, the midnight prayer over the Churban that my father, mekubal Rav Yitzchak Aharoni, would recite with such intensity that we could practically see the destruction in front of us, and another is Kiddush. Abba would stand at the head of the table like a king over his battalion, while the entire family, about 20 of us, would wait breathlessly. Every Shabbat, I felt the Shechinah coming into to our house.

With his fluency in Arabic, he became a valuable information-gatherer for the Irgun paramilitary underground, mingling in Arab neighborhoods and even mosques. Soon he began hearing a name with increased frequency and uttered with reverence and adoration: Adolf Hitler, friend of the notorious Jerusalem mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini.

And then, in an ironic twist, Sika Aharoni, who had battled the British for so long, actually joined forces with them in an operation meant to thwart the Nazi incursion into the Middle East. In May of 1941 he and his good friend Yaakov Tarzi, together with Yaakov Meridor and Irgun commander-in-chief David Raziel, were sent to Iraq on behalf of the British army to help defeat the Nazi-backed Rashid Ali al-Gaylani pro-Axis revolt in the Anglo-Iraqi War.

Raziel, born David Rozenson, immigrated from Russia to Palestine with his family in 1914, when he was three. Raziel, who studied for several years at Yeshivat Mercaz HaRav and was a regular chavrusa of Rav Tzvi Yehudah Kook, was deeply religious and never compromised on his principles, even through years of reprisal attacks against the rioting Arabs and subhuman prison incarcerations by the British.

In 1937 he was appointed by the Irgun as the first commander of Jerusalem district and a year later, as commander of the entire organization. After years of being pursued by the British, with the Nazi threat hovering over the Arab states and Palestine as well, the Irgun declared a cessation of anti-British activities and would even take their best men for a British-sponsored sabotage and intelligence operation against the Germans and their Iraqi allies, who had set up military bases in Iraq.

Yaakov Aharoni, who was 20 at the time, remembers the feeling of desperation: Germany had already taken over most of Europe and its expeditionary force in North Africa threatened the borders of Egypt and had infiltrated French-backed Syria and Lebanon, after French army aligned with the Nazi-sponsored Vichy government. At the same time, the pro-Axis revolt of Hitler-ally Rashid Ali al-Gaylani broke out in the Anglo-Iraqi war, his forces having besieged the large British base in Habbaniyah.

Still, the summons to go on a secret mission to Iraq came as a surprise for Aharoni.

“In the middle of the night,” he recalls, “one of the Irgun commanders knocked on my window and told me to follow him to a little apartment in the Bukharim neighborhood of Jerusalem. David Raziel and Yaakov Meridor were there, along with a lawyer named Yitzchak Berman, who was the liaison between the Irgun and the British authorities. My good friend Yaakov Tarazi also came to the meeting and I was asked to join them.

“Around dawn, our little group took a taxi to the Tel Nof airstrip near Tel Aviv, but I still had no idea where we were going. Until Raziel turned to me and whispered, ‘We’re going out to help the British strike the great enemy of our people, and at the same time help save Jews from danger.’

“The plan was to infiltrate Baghdad, which was under the control of the Iraqi rebels, and blow up the fuel tanks used by the German air force in Baghdad to bomb British military targets, especially the British base in Habbaniyah.

“It turned out,” Aharoni continues, “that Raziel actually had a second goals in addition to wanting to help the British. His plan was to capture or kill the ruthless, Jew-hating mufti, Hajj Amin al-Husseini, who was in Baghdad at the time.”

The mufti had become chummy with Hitler, and was paid to make anti-British broadcasts in the Middle East to mobilize support for German among the Muslims and urge Arabs to attack Allied forces and kill Jews.

U

pon takeoff, to Aharoni’s great surprise, David Raziel took out his tefillin, a pocket Mishnayos, and a siddur, and recited Tefillas Haderech. “I didn’t know too much about Raziel, or even that he was so religious,” Aharon says, “but I thought to myself, if the Irgun commander is saying Tefillat Haderech and laying tefillin, this mission must be pretty dangerous.”

When the plane landed at the British airport in besieged Habbaniyah, a number of British officers, plus the ousted Iraqi prime minister and two of his officers, were waiting for them.

David Raziel didn’t waste time. He ran to the base headquarters to arrange the operation, and to arrange something else as well.

“When he returned, he told us we were only to eat kosher food,” says Aharoni. “He told us, ‘I’ve never eaten treif, and I suggest you don’t either.’ Of course, I never did either, even during intelligence operations, but Raziel’s conviction was amazing. The prepared meals were replaced with biscuits, jam and poached eggs. Later, I was surprised again: Raziel davened Arvit before going to sleep.

“In the morning, we learned that the British had beaten back the rebels in Fallujah, so it was decided that we would go to Fallujah to obtain information about Iraqi rebel positions along the route between Habbaniyah and Baghdad. A jeep picked us up, and soon we were on the way to Fallujah, but on the way, we reached a water-flooded area about a mile wide, and as there was only one boat belonging to a local Kurd that could hold just two people at a time, we decided to split up. Meridor and I went first. Twenty minutes later, back on dry land, we saw Nazi planes hovering overhead, pointed toward the military base we’d just left. A few minutes later we heard a series of explosions and saw smoke mushrooming up from the direction of the camp.”

Meridor and Aharoni were offered a place to stay in any of the abandoned building in Fallujah, but due to security concerns they decided to return to Habbaniyah to sleep, despite the travel danger. Around midnight they returned to the British base.

And were hit by a tragedy that still makes Aharoni tremble.

“As soon as we opened the door, we felt something was wrong,” Aharoni relates. “Yaakov Tarazi was standing there, pale as a ghost. Next to him was a lump on the floor, covered with a sheet. He told us, sobbing, ‘He’s dead! David Raziel is dead!’

“We just stood there in shock. Finally, Tarazi was able to get the story out. ‘When you got on the boat,’ he told us, ‘Raziel decided to try and find another way to Fallujah. We continued on in the military jeep, when we heard the unmistakable shriek. We were being bombed. Raziel and the British operations officer were killed on the spot and the driver was seriously injured, losing both his legs. But somehow, I didn’t have a scratch.’

“The next morning, I took David Raziel’s tefillin and wrapped myself in them. Then I went up to Meridor and told him, ‘The commander may have been killed, but we must carry out the mission — precisely now, despite this setback.’ ”

Meridor was impressed by Aharoni’s determination, and sent him off together with Tarazi — dressed as locals — to make their way toward Baghdad and report on the status of the roads. If the roads were clear, the British would be able to advance. And so, Aharoni and Tarazi made their way into the unknown.

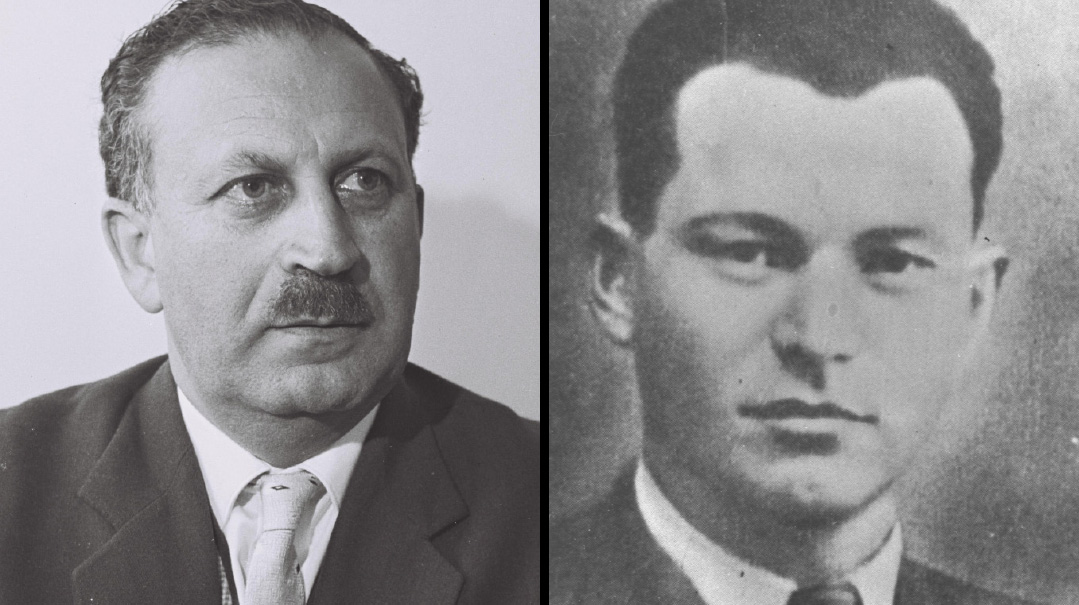

Yaakov Meridor (left) and David Raziel (right). Could their little group sabotage the pro-Nazi revolt in Iraq?

They slept overnight in a Bedouin tent and were hosted by Arab villagers along the way, peddling the story that they had been with a pro-rebel convoy that had been bombed by the British, and were now on their way to Baghdad to find their older brother. At every stop along the way, they were able to garner valuable information and somehow at the last minute deflect suspicion — until their last stop at the entrance to Baghdad where, says Aharoni, they were almost executed.

“We sat down to eat Kurdish pita bread that we had stocked up on when we set out, and then an Arab approached us. We offered him to eat with us, but he only took a pita and left. Twenty minutes later, he returned with two other Iraqis who dragged us into an abandoned police station.

“It turned out that the Arab to whom we gave the pita suspected us of being spies, precisely because of the thin Kurdish pitas we had — the Kurdish enemy would never give pita bread to pro-rebel Iraqi travelers. Suddenly we found ourselves surrounded by about 20 bloodthirsty thugs, and were sure we’d met our end. The head of the group began interrogating us about Islam, asked me about verses from the Koran, and even asked me to describe the interior of the Al-Aqsa mosque — and because of my espionage work with the Irgun, I was able to answer all his questions.

“Once I’d ‘proven’ that we were Muslims, reiterating the story of how we were two orphans on our way to Baghdad to find our brother and begging for mercy, we were released and even escorted out with blessings and a cluster of dates.

“Finally, we were on our way back to the British military outpost in Habbaniyah, where Kurdish soldiers were standing guard. When we met up with Meridor, who would take over as commander of the Irgun, he was shocked to see us alive and well. He told us that right after he said goodbye, Officer Dawson, the British liaison, told him, ‘Forget about them. We’ve sent out local intelligence personnel, Muslims who are experts in espionage, intelligence and sabotage operations, and all of them have been caught and eliminated, and you hope that two Jewish boys in foreign territory will succeed? Forget it, you’ll never see them alive again.’ Meridor said that at that moment he saw black. ‘Raziel is gone, and now these two?’ he thought hopelessly.

“We were able to give the British important intelligence information that helped them in their ultimate victory, and that night our mission ended,” Aharoni says. “A few hours later we were in a military aircraft back to Eretz Yisrael.”

But one of them didn’t return. David Raziel was buried in a bunker in the British military cemetery in Habbaniyah. Fourteen years later, in 1955, his remains were exhumed and transferred to Cyprus, and finally in 1961 to Jerusalem’s Har Herzl military cemetery.

Mechachem Begin after the Kosel’s liberation. As a former Irgun commander, he never forgot those days when the Western Wall stood in shame

B

ack in Eretz Yisrael, Aharoni and the Irgun again took up their revolt against the British, who continued to tighten the screws on the Jewish yishuv. And on Yom Kippur of 1944, he made another appearance.

Before the Yamim Noraim, the question of shofar-blowing at the Kosel was raised again. This time the Irgun, now led by Menachem Begin, decided not to confine itself to bringing in a single shofar-blower to mark the end of Yom Kippur. Several weeks before Rosh Hashanah, the Irgun began to issue warnings to the British to keep away from the Wall, and announced that any policemen found near the Kosel on Yom Kippur would be punished.

As Yom Kippur approached, the warnings were reiterated daily. This was one of them: “Any British constable who will commit acts of violence near the Western Wall on the Day of Atonement and, in defiance of the moral law of civilized people, will disturb the worshippers assembled there and will desecrate the sanctity of prayer will be regarded as a criminal offender. Visitors or passers-by, whether Muslims or Christians, will not be disturbed in their approaching or passing the Western Wall.”

The tension mounted. The Irgun created the impression that it intended to concentrate large forces in the Western Wall area and resort to violence if needed. But this was, in fact, a diversionary tactic, as the Irgun had an entirely different plan up its sleeve — attacking four British police installations around the country as soon as Yom Kippur ended. Meanwhile, the British authorities heeded the Irgun’s warnings, and not a single British policeman was present in the Wall area on Yom Kippur. The blowing of the shofar after Neilah took place without a hitch, yet the British detectives who were on the periphery couldn’t understand why there were no Irgun forces out. They would soon find out though — because right afterward those very Irgun forces were attacking British stations in Haifa, Kalkiliya, Gedera, and Beit Dagan — the latter under the command of Yaakov Aharoni.

Aharoni was arrested multiple times by the British and the prisons in Jerusalem, Netanya, Haifa and Acco became familiar territory. In 1945 he was exiled to Sudan and then transferred to Eritrea (along with former Prime Minister Yitzchak Shamir), and was finally repatriated in the summer of 1948, after the British were long gone and Israel gained independence.

With the formation of the IDF, Aharoni served in military intelligence, then went on to university to earn degrees in education and literature, served as a government attaché in several countries, was a high school principal, and over the years authored ten books.

But throughout all his adventures, nothing, he says, compares to those shofar blasts at the end of Neilah in 1938. “For me it was the beginning,” he says, “but it set the tone for everything that was to come.”

—Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report

Tekiah Gedolah

Rav Moshe Tzvi Segal, a Lubavitcher chassid who was active in the struggle to free Eretz Yisrael from British rule in the two decades before the War of Independence, was 26 years old when he made history by defying the British ban on blowing the shofar at the Kosel. Following Neiliah in 1930, his tekios insured that the shofar would be blown every year from then on. The following is a small excerpt from his memoirs:

In those years, only a narrow alley separated the Kosel and the Arab houses on the other side. The British Mandatory government prohibited placing a Torah ark, tables, benches, or even a small stool in the alley in front of the Kosel. They also instituted ordinances designed to humiliate the Jews: praying out loud, lest one disturb the Arab residents, reading the Torah (those praying at the Kosel had to go to one of the synagogues in the Jewish quarter for the Torah reading), and blowing the shofar on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. British policemen were stationed at the Kosel to enforce these rules.

On Yom Kippur of 1930, during the short break between Mussaf and Minchah, I overheard people whispering to each other: “Where will we go to hear the shofar? It will be impossible to blow here. There are as many policemen as there are people praying…”

I listened and thought to myself: Can we possibly forgo this proclamation of G-d’s sovereignty over the world?

I approached Rav Yitzchak Orenstein, rav of the Kosel, and said, “Give me a shofar. I’m going to blow.”

“What are you talking about? Don’t you see the police?”

“I’m going to blow.”

The Rav abruptly turned away, but not before he cast a glance at the shtender at the left end of the alley. I understood the hint: There’s a shofar inside the stand.

When the end of Neilah approached, I walked over to the stand and leaned against it. I opened the drawer and slipped the shofar into my shirt. I had the shofar, but what if they saw me before I had a chance to blow it? I turned to person next to me and asked to borrow his tallis (I was still single then, so I didn’t have one). He might have thought it was a strange request, but he handed it to me without a word.

Here I am under no foreign dominion, save that of my Father in Heaven, I felt as I wrapped myself in the tallis. When the closing verses of the Neilah prayer — “Shema Yisrael,” “Baruch shem kevod” and “Hashem Hu Ha’Elokim” — were proclaimed, I took the shofar and blew a long, resounding blast.

After that, everything happened very quickly. Many hands grabbed me, and before me stood the police commander, who ordered my arrest.

I was taken to the Kishleh prison, where an Arab policeman was appointed to watch over me. Many hours passed, but still I wasn’t given any food or water to break my fast. At midnight, the policeman received an order to release me, and he let me out without a word.

As I exited the gate, I met a group of young men from the Mercaz Harav yeshivah.

“My friends!” I called out to them. “What are you doing here at midnight?”

They told me that immediately after I blew the shofar, some Mercaz Harav students who were there hurried off to tell Rav Kook what had happened. Rav Kook hadn’t yet broken his fast, yet on the spot he called the High Commissioner’s secretary, demanding my immediate release. When his request was turned down, Rav Kook informed the secretary that he would not break his fast until I was freed. The High Commissioner resisted for several hours, but finally, out of respect for the chief rabbi, he had no choice but to set me free.

Rabbi Moshe Segal was one of the first Jews to move into the Old City of Jerusalem after its liberation in 1967. Immediately after the paratroopers captured the Old City, Segal arrived, determined to take up residence there. The soldiers on guard were reluctant to allow him in, explaining that they could not take responsibility for his safety. “We have received a gift from G-d,” he exclaimed. “Do you really expect me to remain outside while the Arabs are still inside?” In the end he was escorted through the streets with an armored jeep.

Rabbi Segal passed away in 1985 — on Yom Kippur.

(Excerpted from a translation by Yanki Tauber for chabad.org.)

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 928)

Oops! We could not locate your form.