Read in the Original

| August 30, 2022From the Rambam’s Peirush Hamishnayos to Chovos Halevavos, many of our classics were actually written in a foreign language — Arabic

Photos: Ezra Trabelsi

It’s surely one of the most curious phenomena in the field of Jewish book titles. Just imagine learning a chassidic sefer, such as Noam Elimelech in Polish, a scholarly compilation such as the Ketzos Hachoshen in Lithuanian-Russian, or a sefer by an Ashkenaz Rishon in German.

And yet, for some reason, many of the Torah commentaries and works on Jewish thought and halachah from the sages of Spain in the Middle Ages were written in a foreign language — Arabic. We’re not talking about some obscure works, but well-known seforim such as Rambam’s Sefer Hamitzvos, Peirush Hamishnayos and Moreh Nevuchim; Emunos Vedei’os by Rav Saadya Gaon; Chovos Halevavos by Rabbeinu Bechaye; Rav Yehudah HaLevi’s Kuzari — and so many more. And we learn them all today only in the merit of the diligent translators who over the centuries have made them accessible to us.

Most surprising is that all of these gedolim were fluent in Lashon Kodesh and even wrote in it. Why then, did they specifically put out these works in Arabic?

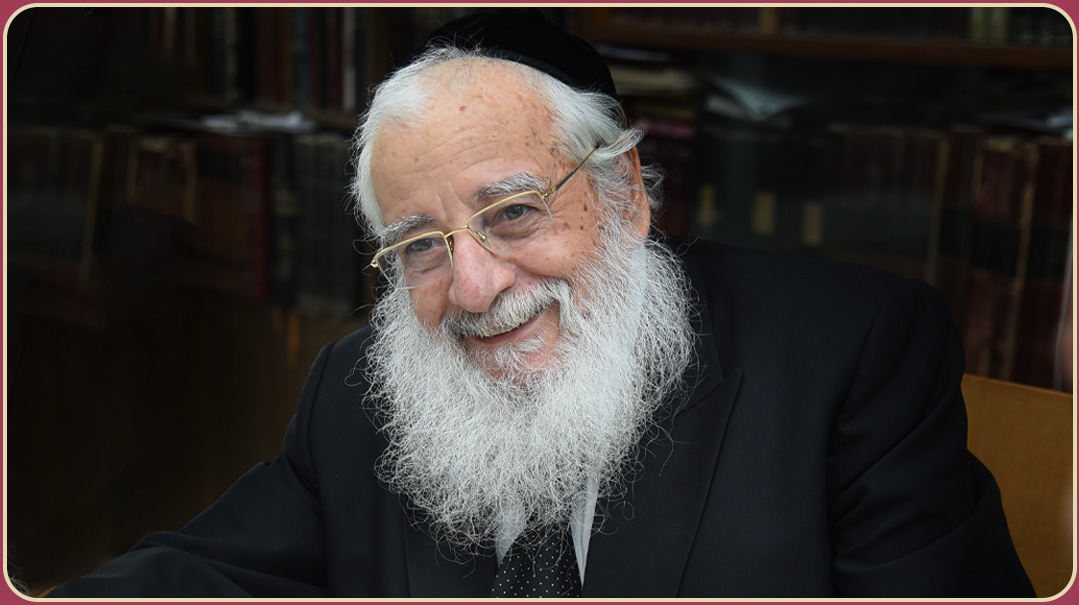

One person in our generation who can shed light on this is Rav Pinchas Korach, a marbitz Torah and one of the most distinguished Yemenite rabbanim in Israel. He is the rav of Beis Medrash Shaarei Halachah Bnei Brak, and, although he’s past 80, he still spends his days traveling far afield to deliver shiurim in venues around the country. Rav Korach is also a prolific author, having penned some 20 well-known works on halachah and mussar. One recent work is a new translation of a work called Katab Alkafiya Alabadin – or in its more recognizable Hebrew name, Hamaspik L’Ovdei Hashem, written by Rabi Avraham, the son of the Rambam.

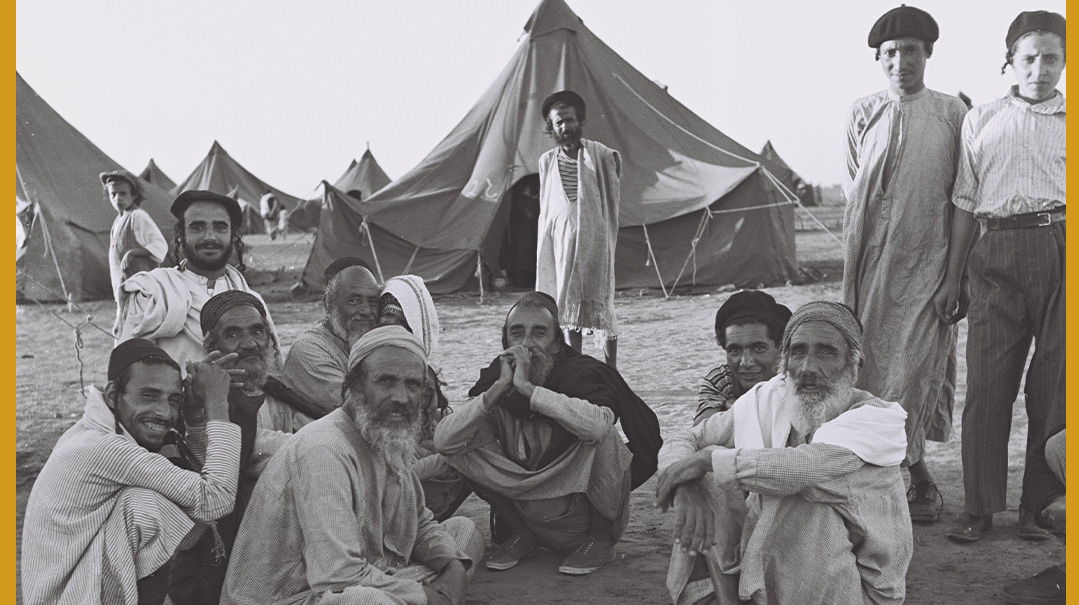

When Rav Korach’s family arrived to a transit camp in Eretz Yisrael in 1950, his father, a mechanech from Sana’a, fought unconditionally for his family’s religious rights and chinuch for his children

The first thing one receives upon entering Rav Korach’s home on Devorah Haneviah Street in Bnei Brak is a lesson in humility: Rav Korach refuses to sit at the head of the table during the week. “That,” he says, “is for Shabbat.” Still, the living room is so neat and orderly it looks like it’s set for company.

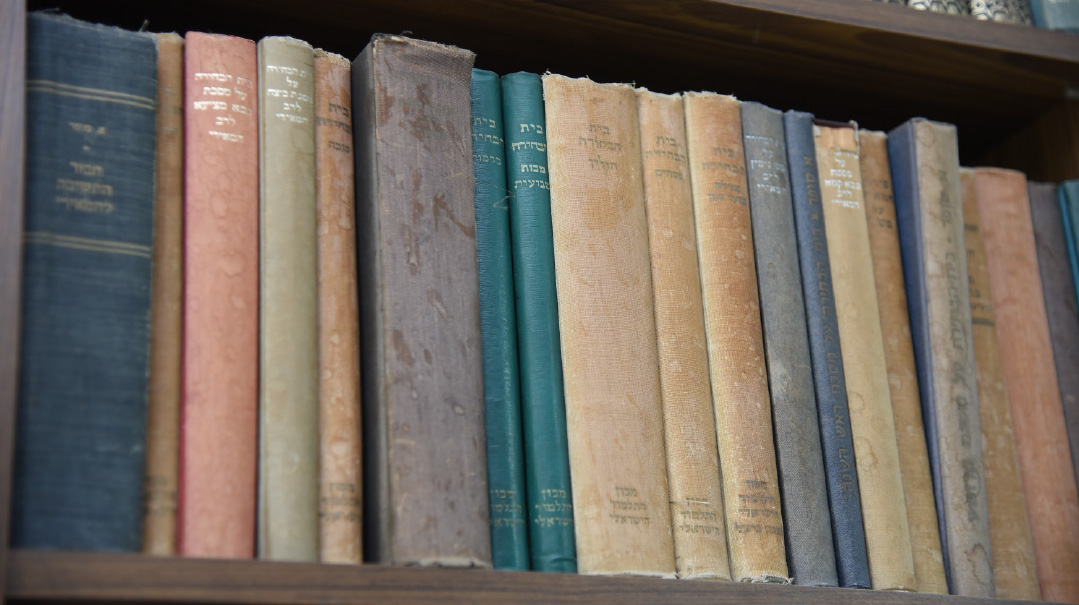

In addition to all the standard volumes on the shelves, a quick glance at the packed bookcases makes it clear that there is an entire trove of seforim in which the sages of Yemen are proficient, yet are generally unfamiliar to others. And on the wall in a corner of the room not covered by bookshelves is a photo gallery of the Korach ancestors of the last generations, all distinguished rabbanim in Yemen. There is Mori Chaim Korach ztz”l, the venerated gadol of his generation, his oldest son Mori Yichye Korach, who moved to Egypt and served there as a rav, Mori Shalom Korach, and Rav Yosef Korach, Rav Pinchas’s father.

But while Rav Pinchas Korach is the next link in the Yemenite chain, he’s also a bridge to the mainstream yeshivah world. When his family arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1950, he was one of the lucky ones, remaining in a Talmud Torah framework instead of being pushed into public school.

“The religious challenges were very difficult then and not too many could withstand them, but my father was very strong, a chinuch personality who back in Sana’a established and ran the local school. When we came here, he fought for chinuch not only for us, but for all the immigrants around us. Some people tried to persuade him to send his sons to work in agriculture to help support the family, but my father vehemently objected. And he pleaded with people not to send their children to government schools.”

The family lived in public housing in Ramat Gan, where young Pinchas learned in the Yesodei HaTorah cheder before moving on to Rav Yaakov Edelstein’s yeshivah ketanah in Ramat Hasharon. From there he went to Ponevezh, where there were other Yemenite bochurim as well: personalities such as Rav Shlomo Korach, who would become rav of Bnei Brak, Rav Azariyah Bassis, who would become rav of Rosh Ha’ayin, and others. He even learned Yiddish.

“The shiurim were in Yiddish, so I took a chavrusa,” Rav Korach remembers. “I helped him with the learning and he helped me learn Yiddish. Pretty soon I got used to it, and I actually found a lot of geshmak learning in Yiddish.” To this day, Rav Korach’s speech is peppered with “yeshivish” and Yiddish.

Rav Korach explains that Yiddish to that generation was like Judeo-Arabic at the time of the Geonim. “Already at the time of Rav Saadia Gaon at the beginning of the tenth century, that was the main language, yet Rav Saadia was probably one of the first who actually wrote his works in this language. The people of the time wanted the leaders to write their teachings in a language everyone could understand.”

At the time, all the books on wisdom, medicine and philosophy were written in Arabic, the language of expression for intellectual matters. The sages, in fact, were proud of being able to express themselves in it.

“And as we know, the Rambam also wrote his seforim in Arabic,” says Rav Korach. “It’s interesting that his most famous work, Mishnah Torah, he wrote in Lashon Kodesh, presumably because it’s a halachic sefer, and the language and terminology is extremely exacting — the Rambam didn’t want anything ‘lost in the translation.’ But in matters of thought, emunah, and hashkafah, he wrote in Arabic. In contrast, the talmidei chachamim of Ashkenaz only wrote in Lashon Kodesh, perhaps so as not to secularize the language of learning.”

However, while the language these scholars used was literary Arabic (which is consistent through all Arabic countries, as opposed to spoken Arabic, which has varied dialects), the alphabet was Hebrew. Their objective was to make their Torah accessible to the masses of their generation in the most understood manner, and that meant Hebrew letters.

“The Yemenite Rishonim used Arabic, both in sifrei machshavah and philosophy, Rav Zechariah Harofei wrote Midrash HaChefetz in Arabic 600 years ago,” Rav Korach explains. “But the use of the language eventually diminished, and the seforim authored since by the Yemenite chachamim were authored in Lashon Kodesh.”

Rav Korach is fluent in Arabic from his childhood in Sana’a, Yemen, but although he knows the rudiments of Arabic script, he, too, prefers to use Hebrew letters when writing the language.

“The truth is that I do know how to read the Arabic script,” he says, “but in order to really be fluent I’d have to dedicate a lot of time to it, and for me that would be bittul Torah.”

But centuries ago, it was considered a good investment of time. Rav Yehudah Ibn Tibon, patriarch of a family of translators from Grenada, Spain, and perhaps the leading translator from Arabic of all time, urged his son Rav Shmuel (who later translated Moreh Nevuchim and parts of Peirush Hamishnah from the Rambam) to learn Arabic script by taking one of his favorite books in Arabic and copying it. Rav Yehudah Ibn Tibon translated Emunos Vedei’os, Sefer HaKuzari, Chovos Halevavos and others well-known seforim.

There were two prominent seforim that the Yemenites of old studied widely. One was the Tafsir, Rav Saadya Gaon’s translation of the Torah into Arabic, which for generations was part of the reading of shnayim mikra v’echad targum. (And one of the well-known customs of the Yemenite community is to read the Targum together with Krias HaTorah.) In fact, Rav Yehudah Ibn Tibon told his son “to read the Arabic seder every Shabbos,” meaning the Tafsir, so that he should acquire knowledge and comprehension in Arabic, and that would help him in his work translating to Lashon Kodesh.

“In previous generations, they were fluent in Tafsir,” Rav Korach affirms, “but about a hundred years ago, this study was neglected by most people, and only a few individuals kept it up.”

The second sefer was the Alsharch, a commentary on the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah, compiled by the sages of Yemen between the 13th and 16th centuries. The Rambam was, and remains, the primary halachic source for the Yemenite community.

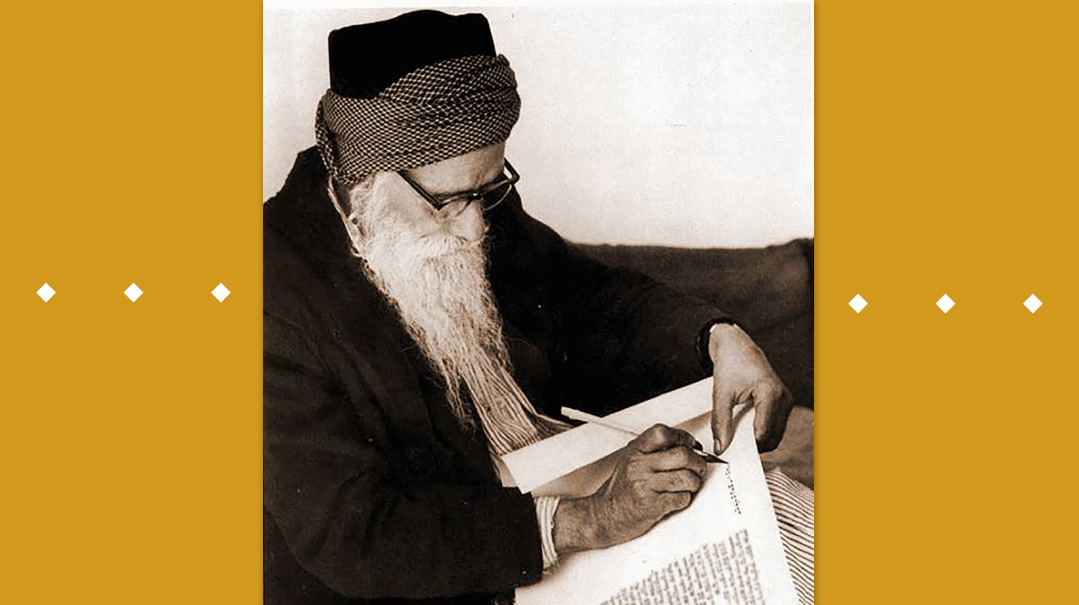

“On Friday nights, they would rise after chatzos and go to the beit medrash, where they would learn Mishnah with the Rambam’s commentary in the Arabic original. Likewise, there were Torah sages and individuals who delved into the mussar and machshavah works of the Rishonim, and they certainly learned in the original Arabic texts, as they were written.”

Yet if the Yemenites essentially spoke Arabic, how were they also able to excel in the knowledge of Lashon Kodesh and in their unique pronunciation?

“It came with great effort,” Rav Korach says. “We began learning and reviewing kriah from an early age, with the Mori, who strictly monitored our dikduk and the precision of our reading. This is something we’re brought up with from a very early age. I guess that’s why they asked me to be the baal korei when I came to Yeshivat Hasharon — although I did have to alter the pronunciation and the accent a bit.”

Today there seems to be a trend to go back to the traditions — many Yemenites maintain their “simanim” — their peyos — and some have gone back to original Yemenite clothing — think Rabbi Amnon Yitzchak. Rav Korach is, of course, a huge proponent of reviving the minhagim, but he is also more of a blender into mainstream Torah society than a separatist, and is concerned that bringing back the traditional dress will interfere with that. Many years ago, he says he asked the Steipler if people should be makpid to keep the simanim but the Steipler felt (at the time) that it might cause a rebellion among the young people.

Rav Korach, who has translated a number of the Rambam’s seforim and those of other Rishonim, says it’s a skill that’s been passed down in the family over the generations.

“My father was known as one of the experts in translating from Arabic,” Rav Korach notes. “He didn’t do it for a living, but for the sake of spreading Torah. For example, the Shu”t HaRif, published in 1975 by Rav Dovid Tzvi Rothstein, was translated by my father. He was actually a partner in the translation of other works, not all of which were attributed to him.”

He shares a moving childhood memory: “On Friday nights, at three in the morning, my father would wake me up so that I could take part in the special study of Mishnayos with the Rambam’s commentary. There were elders of Yemen seated there, and I picked up both the language and the content.

“But I had no appreciation for it at the time,” Rav Korach admits. “I would complain at having to be awakened so early, when everyone else my age was still sleeping. But my father wanted to accustom me, and indeed, the habit became so ingrained that I’m still doing it to this day. Each Shabbos we wake up at that hour and learn Mishnah with those who want to listen.” Rav Korach makes it sound like he rolls out of bed into the beis medrash, but in fact Beit Medrash Shaarei Halachah, the shul he founded in 1986, is on the outskirts of Bnei Brak and quite a walk from his home — especially at 3 a.m.

Some of the seforim he’s worked on were already translated in the past. So why bother translating them again?

“Unfortunately, in many cases, the translation is distorted and full of mistakes. Sometimes that’s because the Arabic source itself was not completely correct, and when translators based their work on those mistakes, it leads to an inaccurate translation.

“But what’s more important is that translation requires a double understanding, both of the source language and the Torah language. There’ve been all kinds of translators through the generations who were fluent in Arabic, but they didn’t know how to learn, and did not always understand the concepts correctly. The Arabic language is very rich and elegant. There are words with multiple meanings, and the translator also has to know enough to adapt the translation to the context. The Rambam, in a letter to Rav Shmuel Ibn Tibon, wrote that first of all the translator has to understand the subject being discussed, because if not, his copy will certainly be distorted. I’ve found many distortions of the text because of a lack of understanding of the context — this is a widespread problem among translators, and that’s why the translations must be checked over and over.

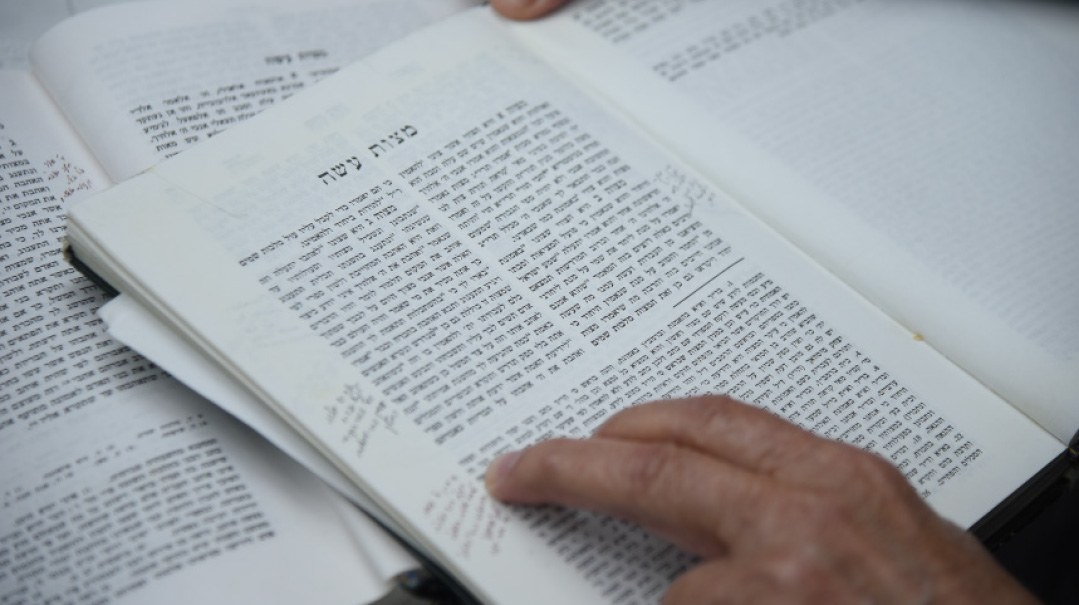

“I’d worked on the Peirush Hamishnayos L’Rambam in Seder Taharos,” Rav Korach continues. “There were a number of translations to work with, most of which were edited by Torah scholars. However, about three years ago, I was asked by Rav Shlomo Zalman Weissenstern, who was working on Maseches Mikvaos, to edit the old translation of the Peirush Hamishnah. Indeed, there were many inaccuracies there that we honed in on, and sometimes, as the result of the corrections, all kinds of complex questions are finally resolved. In fact, one day, when I corrected a mistranslation, I noticed that suddenly a serious question of the Chazon Ish was no longer relevant. I went to Rav Chaim Kanievksy and asked him if it’s appropriate to note this. Rav Chaim instructed me to write clearly that the Chazon Ish wrote his question based on the translation that he had available. But after the work was edited and corrected a number of times, Rav Chaim said to me, ‘Why make latess — patches? Just republish the entire work.’

“My brother, Rav Ezra Korach, one of the veteran lomdim in Kollel Ponevezh, did the work, encouraged by Rav Chaim. He retranslated the entire Peirush Hamishnayos over four years, and in the end, his translation was printed by Machon Hama’or.

“Today, we don’t need to know Arabic to have access to the gedolim of the previous millennium — all their holy writings have already been translated. And their neshamos are surely overjoyed. Even the Rambam, who wrote so many seforim in Arabic, believed the primary specialness of his halachah seforim was inherent in their Lashon Kodesh.”

As if to prove his words, Rav Korach pulls out a copy of Iggeres HaTeshuvah and finds a letter from the Rambam to a Jewish merchant from Baghdad who struggled to read Hebrew and implored the Rambam to translate his works of halachah — not just machshavah — into Arabic. The Rambam turned down the request and wrote, “I do not want, under any circumstances, to publish them in Arabic, because the pleasantness will be lost.”

Two indispensable seforim to the Yemenites were Tafsir, Rav Saadya Gaon’s translation of the Torah into Arabic, and Alsharch, a Yemenite commentary in Arabic on Rambam’s Mishneh Torah

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 926)

Oops! We could not locate your form.