Border Ahead

I was just a teenager, but I knew I had to leave Syria. Without a smuggler, could I possibly escape on my own without being caught or shot?

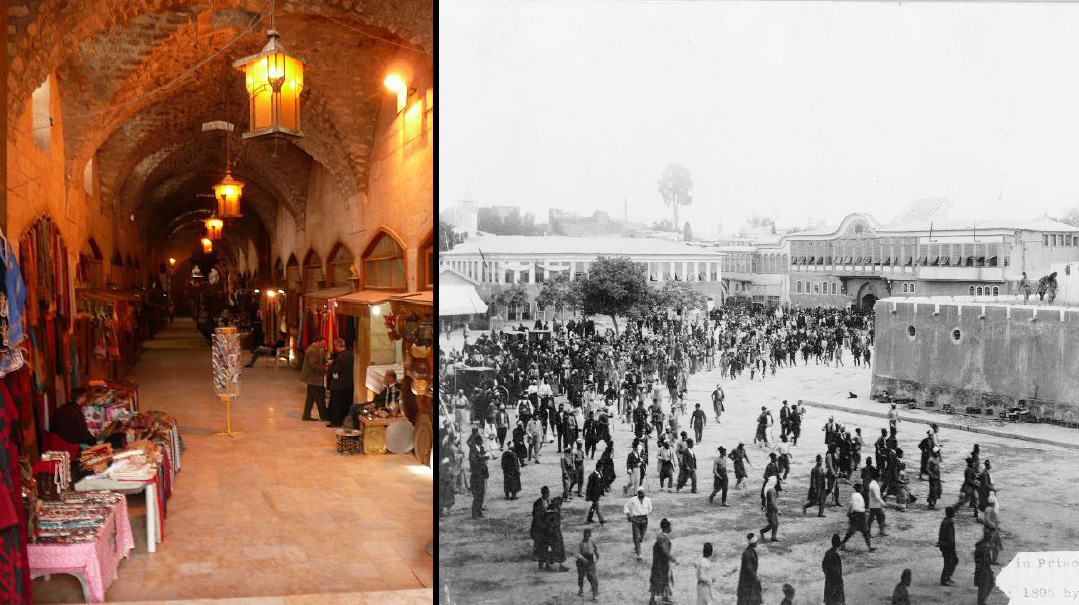

Photos: AP Images

As told to Shira Yehudit Djalilmand by Rabbi Isaac Farhi

I remember my childhood in Aleppo, growing up in a loving family but surrounded by fear. One of my most vivid memories is from 1960, when I was just seven — my brother Dodi burst into the house shouting that our father had been taken to prison. It was illegal for Jews to emigrate from Syria, but as a prominent member of the Aleppo Jewish community, my father often helped prepare documents to help Jews get out, at great personal risk. Now we had no idea if we would see him alive again.

Violence and persecution were nothing new for the Syrian Jews. There was the Aleppo Pogrom in 1947, when the local Arabs, furious about the United Nations’ plan to form a Jewish state in Eretz Yisrael, rioted in the Jewish neighborhoods, burning and beating everything and anyone they found. Seventy-five Jews were murdered that day, hundreds wounded, and synagogues, schools, and stores were burnt to the ground.

B’chasdei Hashem, my father was released after thirty days, weak and malnourished — but alive. Life went on much the same — we were forbidden to leave the country, do business abroad, or hold a driver’s license, and beatings and insults were common. But then in 1965, they caught Israeli spy Eli Cohen.

I remember one morning, my father announcing in shock, “They hanged him! This morning, in Damascus!”

Things suddenly got much worse. Now every Jew in Syria was suspected of being a spy. I was almost bar mitzvah, and one day when I was walking home from the synagogue carrying my new tefillin, I was grabbed by two hefty secret policemen. They actually thought my tefillin were some kind of transmitter to communicate secret messages.

I couldn’t help laughing, and told them, “Yes, I use them to communicate with someone — G-d! Jews pray with them.”

I was lucky — they threw my tefillin back at me and, after a few hard kicks, let me go. But things went from bad to worse. In 1967, Syria and the other Arab states declared war on Israel. After Israel gained control of the Golan Heights following its miraculous victory in the Six Day War, many Syrians who had been living there had to move, and they were seething with rage.

Life became unbearable. It was still illegal to leave the country, but I noticed that more and more Jews were simply disappearing. I was a teen then, I kept my eyes and ears open, and I discovered that most people who disappeared had paid smugglers to take them across the mountains to Turkey — a dangerous and difficult trek. No one ever said goodbye; it was too risky to tell anyone your plans in case someone got caught. But we had to stay put — my father was an important member of the community, and if he were to suddenly disappear, there would be big trouble.

One day, though, I overheard my mother whispering to my father, “We have to get Rosa out of here. That boy Ahmed is trying to force her to marry him. He’ll kidnap her and force her to become Muslim.”

I was shocked. My beloved older sister was to be smuggled out of the country?

About a week later, when I sat down for breakfast, Rosa’s place at the kitchen table was empty and my mother’s eyes were red.

“Where’s Rosa?” my little brothers and sisters wanted to know.

“Gone,” my mother replied in a flat voice.

“Gone where?” my brother demanded.

“Better you don’t know,” my mother said. “Enough that you know she’s safe.”

(Years later I found out that my mother had sold her precious gold bangles to pay the smugglers.)

Two years passed. I was 16 by now and hadn’t really thought about escaping myself. But one night as I was walking home, I happened to glance into my neighbors’ window. The curtains were open and the light was on, but the house had a deserted feel.

They escaped, and they left everything behind, I realized. That was the first time I started to think about leaving myself.

It was 1969, I had no future in Syria, and I made up my mind to escape as well. But how? The smugglers had all vanished — perhaps caught and jailed — and few Jews had managed to get out lately.

I came up with a wild plan, which I shared with a few friends: Rent motorbikes and simply ride up to the Turkish border. My friends thought I was crazy, especially because Jews were forbidden drivers’ licenses. But I found an Arab who cared more about money than the law, and he rented us four bikes. We learned to ride on rough ground, and soon the day arrived.

That morning, I picked up my backpack from beside the door and kissed my mother goodbye as I did every morning before leaving for school. Inside, my stomach was churning. I knew that it might be the last time I would ever see her.

My wild plan turned out to be even wilder than I could have imagined. We actually reached the border safely, at a spot far from the guards. But to our horror, facing us was a big red sign reading, “Danger! Minefield! Live Mines!”

We didn’t know what to do — if we tried crossing and stepped on a mine, we’d be killed instantly. I had another idea — to use donkeys from the nearby village to clear a path for us through the field, one mine at a time. I felt bad for the donkeys, but we had no choice. We had enough money for four donkeys, and after we used up three of them, with most of the minefield still left to cross, we realized it wasn’t going to work. We set the fourth donkey free and headed back to Aleppo.

I was devastated that my escape had failed, but I wasn’t giving up. It was just me and my friend Ezra — our other two friends were too scared to try again — and I knew we couldn’t risk the Turkish border again. Instead, we decided to head for Lebanon.

To get across the Lebanese border, we would need to get past two groups of border guards: Syrian and Lebanese. At the Syrian checkpoint, the guards would demand a Syrian passport — which, as Jews, we didn’t have — but at the Lebanese checkpoint, we wouldn’t need one, because with Syrian identity cards, the Lebanese border guards would think we had legally passed the Syrian border check, and they would give us entry permits for Lebanon. The plan: bypass the Syrian checkpoint, cross the mountains between Syria and Lebanon, a no-man’s land, and make it to the Lebanese checkpoint.

But we had another problem. Our ID cards had “Musawi” (follower of Moses) stamped in red on them, so we steamed open the plastic covers, switched the pictures to photographs of us dressed as Muslims, and changed our names from Zaki (Isaac) and Ezra to Abu Ali and Abu Hassan.

Ezra and I bought secondhand Muslim clothes from the souk with money we’d saved from odd jobs, and then we were ready to go. Once more, I had to leave without telling my parents my plans — and so once more, I picked up my schoolbag, kissed my mother, and walked out the door.

At first, everything went smoothly. No one paid attention to us in the big shared taxi from Aleppo to Hama and then to Homs, the closest big city to the Lebanese border. There we had to take a smaller taxi to Dabousieh, a tiny village right at the border. The driver was inquisitive, but we managed to fob him off with a story about vising our Uncle Hassan.

Providentially, we arrived midafternoon when the villagers were taking their afternoon nap, so there was no one to see us and ask awkward questions. We headed to the border on foot. It wasn’t far, and on our map, we could see the al-Kabir River, which formed the border in the valley between the mountains and the two countries. From high in the hills we could see a thin blue stream winding through the valley below. It looked pretty small, like something we could easily cross. But when we reached the river, we got a nasty shock — this was no narrow stream, but a wide, flowing river. And, like most Syrian Jews, we didn’t know how to swim.

“We’ll just have to try,” I told Ezra. “We can’t give up now!”

Ezra hesitated before nodding in agreement. We stepped in where it was still shallow and moved forward slowly. The water got deeper, and soon it was up to our necks, the current so strong we could barely keep our balance.

Suddenly, Ezra let out a cry as he vanished under the water. Then his head popped above the surface for a moment.

“Help! The current’s dragging me under!”

I grabbed hold of him and tried to drag him back, but the water was too deep and the current too strong. We struggled for what seemed like ages but was really only seconds before finally managing to drag each other out of the water. We collapsed, soaked and exhausted, on the riverbank.

Once we got our breath back, we realized there was only one thing we could do — pray. I sank onto the damp, muddy ground in despair and cried out, “Please, Hashem, find us a way out of here!”

Suddenly, a man appeared — a Syrian Arab who introduced himself as Abdullah. He was trying to get to Beirut to visit his wife in prison, but he didn’t have a passport and was also trying to bypass the border guards. We told him we were going to our cousin’s wedding in Beirut and, like him, didn’t have enough time to get passports. Baruch Hashem, Abdullah believed us, and he told us there was a place farther down that was shallow enough to wade across the river.

Abdullah led us to the spot where the water was so shallow we could see the pebbles on the riverbed. In just minutes, we had made it across — we were out of Syria and in Lebanon! But we couldn’t show our excitement or Abdullah would get suspicious.

After cleaning up a bit, we presented ourselves at the Lebanese checkpoint. Once more, it was clear Hashem was watching over us. The guards, bored and uninterested, barely glanced at our forged ID cards before handing us a stamped paper.

“Your entrance permit. Move along, next!”

Yet our difficulties were far from over. We took a taxi to Beirut, where there was a big Jewish community, but we couldn’t shake off Abdullah. He said he had nowhere to stay in Beirut and, in return for helping us, wanted to come with us to our nonexistent uncle. We didn’t want him to get suspicious, so we had no choice but to agree. It was late when the three of us arrived in Beirut, so we told Abdullah we would go to my uncle’s house in the morning. Abdullah took us to a dingy motel, where we shared one room between the three of us, as none of us had much money. Ezra and I were exhausted but we couldn’t sleep — we were worried about how to get away.

In the end, we decided to sneak out before sunrise. But on the way to the door, Ezra accidently knocked against Abdullah’s bed, and he woke up.

“Where are you running off to?” he demanded.

I had to think fast.

“We’re going to sunrise prayers — it’s Ramadan!” I announced.

Abdullah groaned, turned over, and went straight back to sleep. We grabbed our chance and ran for it.

Now Ezra and I had to find our way to the Jewish quarter. It wasn’t so simple — we were dressed as Arabs. Luckily the taxi driver wasn’t curious and didn’t ask questions, and just ten minutes later we found ourselves standing outside Beirut’s Maghen Abraham Synagogue.

But to our shock, we didn’t quite get the warm reception we had expected. Everyone thought we were Muslims, and even Chacham Shchoud Shrem, the chief rabbi of Beirut, refused to believe our story. We showed him we knew Hebrew, but it didn’t help. We asked for tefillin and joined in the tefillah, praying our hearts out. Afterward, Chacham Shrem said, “I still don’t quite believe your story, but you certainly pray like Jews. You can stay for just the night, because if your story is true, we’ll get in trouble with the Lebanese authorities for harboring you.”

We ended up staying in Beirut for nine months. For two months, we hid in the women’s section of the synagogue, unable to go outside for fear of capture. We saw only the Jews who came to pray and the rabbi’s daughters, who brought us food. Then we moved to the home of a wealthy Jew, where we felt welcome and comfortable, but we were still fugitives in hiding. Twenty-four other Syrian refugees to Beirut joined us.

One day, I felt especially desperate and claustrophobic.

“I didn’t escape Syria to get trapped in Lebanon,” I told Ezra. “I’m going to the government for help.”

It might have sounded like another wild plan, but the Lebanese government had good relations with the Jewish community — in fact, the personal physician of the Lebanese prime minister was Jewish. Even though it was dangerous to be on the streets of Beirut without official papers, I thought if I could reach someone high in the government, I’d have a chance.

With the help of the prime minister’s Jewish physician, I managed to speak with one of the top government officials. Within three days, we were informed of a plan to get all 26 of us across the border into Israel.

Getting to the Israeli border, however, wasn’t simple. We had to cross territory controlled by Yasser Arafat and the PLO, which had recently planted their headquarters there after being expelled from Jordan. We dressed up in robes and kaffiyehs to cover our heads and faces, and the Lebanese army drove us to the border of the PLO-controlled territory in Southern Lebanon. The army had marked the ground with a white line for us to follow.

“It will lead you to a spot on the border where the Israeli army will be waiting for you,” the Lebanese soldiers said.

After hours of silent, tense walking, the light from our one flashlight started growing weaker until we could barely see the white line. Finally, the flashlight gave out altogether. We had to stop and wait for sunrise, but when, with the first rays of the sun, we got up to continue, there was no white line. We must have gone off course when the flashlight was giving out.

One thing we knew: We couldn’t stay where we were. I knew the direction we came from, and we figured our best bet was to move in the opposite direction. We walked and walked, on and on. Soon we saw a mountain, and as we moved forward, we saw the border fence with rolls of barbed wire across the top. On the other side of the fence were houses and signs in Hebrew. We’d made it!

Well, almost. The problem was that Israel was on one side of the barbed wire fence, while we were on the other. We were supposed to meet with Israeli soldiers who would take us across, but now that we had lost our way, we had no idea where to find them. And there was no way to scale the barbed-wire fence.

“Look, the soil is soft here,” I announced, pointing under the fence. “We can dig with our hands and make a hole big enough to crawl underneath.”

We dug and dug, until there was just enough room for us to squeeze under the fence. We had barely all made it through when suddenly, an IDF border surveillance tank swerved around the corner, heading straight for us. We didn’t know what to do, but suddenly, one of the refugees lay down on the ground. Another boy joined him, and then another, until all 26 of us were lying on the ground, in the path of the approaching tank.

It ground to a halt and soldiers jumped out, aiming their guns at us. We looked suspicious, and we didn’t know enough Hebrew to explain that we were Jews, not Arab terrorists.

“Shema Yisrael!” I shouted.

Within seconds, everyone else joined. The soldiers lowered their weapons and advanced cautiously.

“Who are you?” they demanded.

In a confused mixture of Arabic and Hebrew, we managed to explain that we were the Jewish refugees from Syria.

“We’ve been looking all over for you!” the soldiers exclaimed. “You were supposed to be here hours ago!”

Rabbi Isaac Farhi learned in Yeshivat Porat Yosef in Jerusalem, received semichah, and eventually moved with his family to Deal, New Jersey, where he serves as rabbi of the Edmond J. Safra and Joseph S. Jemal synagogues. Over the years, Rabbi Farhi’s siblings gradually escaped from Syria, but it wasn’t until 1992 that President Hafez al-Assad gave the Jews official permission to leave the country and the entire family was finally reunited.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 922)

Oops! We could not locate your form.